On September 5, 1928, 34-year-old James Eugene Bassett (ca. 1894-1928) travels from Bremerton to Seattle via ferry to meet "Mr. Clark," a prospective buyer for his new 1929 Chrysler 75 roadster. It is the last time he is seen alive by his relatives. Bassett's family reports him missing and on September 13, police in Oakland, California arrest Decasto Earl Mayer (ca. 1894-1938), age 34, and Mary Eleanor Smith (ca. 1866-1966), age 62, in possession of his automobile and personal effects. Mayer and Smith are extradited to Seattle to face a charge of murder, but police are unable to find Bassett's body. Absent the corpus delicti (the substantial and fundamental fact necessary to prove a crime has been committed, such as a victim), Mayer and Smith are charged and convicted of grand larceny in King County Superior Court and sent to prison. Meanwhile law enforcement authorities continue to search for Bassett's body, hoping eventually to charge Mayer and Smith with first-degree murder. Upon appeal, the Washington State Supreme Court will uphold Mayer's conviction but grant Smith a new trial on a technicality. In 1930, Smith will be convicted of grand larceny for the second time and sentenced to serve eight years in prison. Mayer will be convicted of being a habitual criminal and sentence to life imprisonment without parole at the Washington State Penitentiary.

Selling the Roadster

In July 1928, James Eugene "Gene" Bassett (1893-1928), a World War I Army Air Corps veteran, left Annapolis, Maryland, en route to the Puget Sound region, driving a new, 1929 Chrysler 75 roadster in unique three-tone blue. Arriving in mid-August, he stayed with his sister, Emily, her husband, Commander Theodore H. Winters (USN) and their son, 15-year-old Theodore H. "Hugh" Winters Jr. at the Naval Shipyard in Bremerton. A professional stenographer, Bassett had been hired by the Department of the Navy as a civilian secretary, assigned to U.S. Naval Headquarters at Cavite in Manila Bay. He was scheduled to depart for the Philippine Islands, aboard the American Mail Line steamship President Cleveland at 11:00 a.m. on Saturday, September 8, 1928.

After consulting with Commander Winters, who had spent considerable time in the Philippines, Bassett decided to sell his roadster rather than shipping it to Manila. Advertisements for the car first appeared in the Seattle newspapers on Monday, August 20: "Chrysler "75" roadster. 1929 model, only few weeks old. Owner leaving for Orient. $1,600 cash. Phone Navy Yard 331, Bremerton" (The Seattle Times).

On Tuesday, September 4, 1928, a man calling himself "Mr. Clark," arrived in Bremerton to look at the Chrysler. In the presence of the Winters family, he told Bassett the roadster was just what he was looking for, but needed to show it to his "aunt" who lived in Seattle. Clark said if his aunt liked the roadster, he would have a certified check ready for $1,600 and would close the deal. Bassett agreed to bring his roadster to Seattle the following day and show it to Clark's aunt for her approval.

An Odd Telegram

On 9:00 a.m. Wednesday, September 5, Bassett left Bremerton with his automobile aboard the Puget Sound Navigation Company ferry Chippewa for Colman Dock. He told Commander Winters he planned to return that afternoon. At approximately 6:00 p.m., Emily Winters received a Western Union telegram, purportedly from Bassett, advising her he had met a friend, was leaving for Vancouver, B.C., and would return on Friday.

The telegram was perplexing because Bassett had no known friends in the Pacific Northwest, the action was totally out of character, and he had no luggage. He failed to return to Bremerton on Friday, September 7, and the SS President Cleveland sailed from the Great Northern Dock, Pier 41, on Saturday without him. Commander Winters personally searched the steamship before it sailed and requested the captain again search for Bassett during a stopover in Victoria, B.C., but he wasn't aboard. Canadian authorities advised Winters that Bassett's distinctive Chrysler roadster had not crossed the border, and found no trace of him in Vancouver hotels.

Foul Play

On Sunday, September 9, 1928, Commander Winter appeared at Seattle Police Headquarters and convinced Captain Charles Tennant (1875-1933), Chief of Detectives, that Bassett had met with foul play. Chief Tennant immediately assigned detectives to investigate and on Monday began publishing requests for information about Bassett's disappearance in area newspapers. There followed one of the most intense and protracted body hunts in Washington state history.

Tennant obtained a complete description of the 1929 Chrysler from the Maryland Department of Motor Vehicles, including the license plate number, 139-212. With this information, he contacted the Washington Department of Motor Vehicles in Olympia and discovered from licensing bureau clerk, Betty Hettman, that on Thursday, September 6, a man appeared at the Capitol Building and used a typed bill-of-sale, notarized by James Hannon in Seattle, to transfer the title from James E. Bassett to Decasto E. Mayer and purchased Washington license plates, number 336-051, for the car. Mayer was accompanied by an elderly woman whom he introduced to the clerk as his mother. They were seen outside the building replacing the Maryland plates with Washington plates on a fancy blue roadster.

James Hannon, notary public, 525 Union Street, Seattle, told Chief Tennant that at approximately 10:20 a.m. Wednesday, September 5, Clark and Bassett visited his office and paid him to authenticate Bassett's signature on a blank bill-of-sale. Clark explained the details would be filled in later, once the purchase had been finalized. Hannon said no money was paid to Bassett in his presence. It was later discovered that the following day, a man using the name D. E. Mayer hired Mrs. Muriel Mylchreest, a public stenographer at the Tacoma Hotel (destroyed by fire in October 1935) 913 A Street, Tacoma, to fill in the missing information on the bill-of-sale with her typewriter.

Satisfied that Mayer and Clark were the same person, on Wednesday, September 12, Chief Tennant issued a nationwide alert for the automobile, requesting it be seized as evidence and its occupants held for suspicion of murder.

Suspicious and Arrested

On Thursday, September 13, Motorcycle Traffic Officers Henry M. Karmena and Vernon Swart stopped a male, accompanied by an elderly female, driving a blue 1929 Chrysler roadster, bearing Washington license 336-051, entering Oakland, California. Officer Karmena directed the man to drive the car to police headquarters and stepped onto the right running board. En route, he attempted to knock Karmena off the roadster by rear-ending one car, sideswiping another, and driving erratically. Karmena pulled his gun and threatened to shoot the driver if he failed to obey his orders.

At police headquarters, the male identified himself as Decasto Earl Mayer, age 34, admitted he was an ex-convict and had used at least 12 aliases including the name "Earl Montaigne." The elderly female refused to answer questions or even give her name. She was later identified as Mary Eleanor Smith, alias French, age 62. Among their commingled possessions, detectives found Bassett's wallet containing his driver's license and vehicle registration, a belt with souvenir buckle from Yellowstone National Park, and a pair of cufflinks, all identified as belonging to the victim, and a loaded tear-gas gun with a box of cartridges. A search of the vehicle revealed a silver Elgin wristwatch, engraved with Bassett's name and stuffed between the front seat cushions. It was fully wound the time correctly set.

When Chief Tennant learned from the Oakland Police the man calling himself Mayer had used the alias "Earl Montaigne," and heard his physical description, he knew immediately who the suspect was. Tennant had a thick file, including mug shots, dating back to 1915 when Montaigne was arrested in Seattle for carrying a concealed firearm. Over the years, Tennant had traded information with several jurisdictions about the suspect described by Special Agent Deane H. Dickason, Department of Justice, Bureau of Investigation, Butte, Montana, as one of the worst criminals in the entire country. Mayer's first arrest was at age 18 for burglary in Los Angeles in 1912, for which he spent three years in the Whittier state reformatory. Between 1915 and 1926, his record showed numerous felony arrests in Western States burglary, forgery, grand larceny, auto theft and three suspected murders. Mayer had served time in state prisons in Oregon, Montana, Utah and Colorado, and city jails in Los Angeles Seattle, Spokane, Portland and Denver. In 1926, he was sentenced to three years in the Leavenworth Federal Penitentiary for violating the Mann Act of 1910 (also known as the White Slave Traffic Act) which made it a felony to transport a female in interstate commerce for immoral acts. He was released on parole from Leavenworth on July 31, 1928, and apparently came directly to Seattle to hook up with Mary Smith, his alleged mother, and resume their criminal activities.

Hunting Bassett's Body

King County Prosecutor Ewing D. Colvin had a problem. Bassett was missing, but there was no direct evidence that he was dead. On Friday, September 14, Colvin filed an information in King County Superior Court charging Mayer and Smith with grand larceny and requesting a $25,000 bond. Colvin prepared extradition warrants which were signed by Governor Roland H. Hartley (1864-1952) in Olympia on Monday, September 17. That same day Seattle Police Captain William B. Kent, King County Deputy Prosecutor John J. Dunn and Ethel Currier, extradition agent for the prosecutor's office, left on the train for Oakland. As an added precaution to keep the pair in custody, a federal grand jury in Seattle indicted Mayer and Smith for violation of the Dyer Act, interstate transportation of a stolen vehicle.

As the much publicized hunt for any trace of Bassett continued, Chief Tennant received information from Dr. James P. Clark, a Seattle Dentist, that he had leased a house for one year to D. E. Mayer and his mother, Mrs. Mary Eleanor French, on August 20, for $40 per month. The residence, always referred to as the "little brown house," because it had no official address, was located on N 185th Street, between Greenwood Avenue N and Fremont Avenue N, in Richmond Highlands, approximately 10 miles north of Seattle. Chief Tennant searched the residence and found a .30-40 caliber U.S. Krag-Jorgenson carbine, fitted with a silencer, a box of soft-nose Krag ammunition and a set of Maryland license plates, number 139-212, hidden on top of a beam in the basement. On the kitchen table were several classified sections from Seattle newspapers with numerous "Automobiles For Sale" advertisements circled. Remnants of burnt clothing and buttons were found among the ashes in the kerosene-fueled stove and the fireplace

Three people reported that shortly before Bassett's disappearance, their cars had also been advertised for sale. Their stories were remarkably similar, including the description of the potential buyer, introducing himself as "Mr. Clark," who wanted the car and had a certified check for the amount, but first needed to show it to his "aunt" for her approval.

A local grocer, delivering a pound of butter to the "little brown house," reported he had seen Bassett's distinctive, three-tone blue roadster with Maryland license plates standing in the side yard about noon on Wednesday, September 5. After knocking on the front door and receiving no reply, he started toward the back door, but was intercepted by an elderly woman who abruptly took the butter and told him to leave.

At 5:00 p.m., Saturday, September 22, Mayer and Smith, escorted by Captain Kent, Deputy Prosecutor Dunn, and Ethel Currier, left San Francisco aboard the Pacific Steamship Company vessel Admiral Evans, en route to Seattle. Also on board the ship, as evidence, was Bassett's 1929 Chrysler 75 roadster. The Admiral Evans arrived in Seattle at the Pacific Steamship Company docks (now Pier 36-37) at 8:45 p.m. on Tuesday, September 25 and the prisoners were taken directly to the Seattle City Jail and placed in solitary confinement.

On September 28, Seattle attorney John F. Dore (1881-1938) agreed to defend Mayer and Smith in the case. At the initial appearance on October 3, Judge Chester A. Batchelor, at the prosecution's request, scheduled the preliminary hearing for November 26, 1928, to allow the police time to gather evidence to support charges of murder as well as grand larceny. Dore argued the state had no provable case and would first be required produce Bassett's body, then establish the defendants killed him and/or stole his property. He requested the preliminary hearing be held without delay, asserting his client's constitutional rights were being violated When Judge Batchelor denied the request, Dore declared he would carry the fight for an immediate hearing to the Washington State Supreme Court. Judge Batchelor replied that the scheduling of his court calendar was a matter of his discretion alone. "If the defendants are innocent, a little delay will not hurt them," he told Dore (The Seattle Times).

Frustrated by their stoic silence, Chief Tennent employed third-degree interrogation methods, including the injection of "truth serum" (scopolamine) on Mayer and Smith, hoping they would confess to murdering Bassett and divulge the location of his body. On Thursday, October 18, Defense Attorney Dore filed a writ of habeas corpus in King County Superior Court requesting the release of his clients and charging the Seattle Police Department with cruelty and torture. Although Chief Tennent denied the charges, two days later the prisoners were transferred from the Seattle City Jail to the King County Jail. "They're in on a state charge; let the state care for them. We've had them here as long as we wanted them" remarked Captain Kent (The Seattle Times).

On Tuesday, October 23, Superior Court Judge Charles P. Moriarty denied Attorney Dore's writ of habeas corpus, but granted a writ of mandamus, ordering the defendants be given a preliminary hearing on the charges of grand larceny within 72 hours. The judge also issued a restraining order prohibiting the police from employing any violence or torturous methods against Mayer and Smith.

On Thursday, October 25, Prosecutor Colvin filed an information in Superior Court charging each Mayer and Smith with two counts of grand larceny, but not with murder. The first count covered the theft of Bassett's automobile and the second count accused the pair of having stolen his wristwatch, belt, wallet and cufflinks. New arrest warrants were issued and served on the defendants in the King County Jail. The following day, the defendants appeared before Chief Judge William J. Steinert for arraignment and, at Attorney Dore's request, granted a week for the defendants to consider their pleas. On Friday, November 2, both defendants entered pleas of not guilty to the charges of grand larceny. Judge Steinert granted a defense motion to change counsel from John F. Dore to Henry Clay Agnew and scheduled the trial date for December 5. Meanwhile the seemingly endless and futile search for Bassett's body continued.

Trials and Convictions

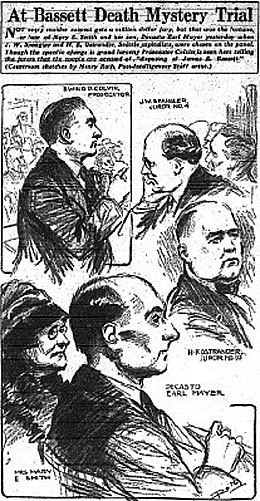

Trial began on Wednesday morning, December 5, 1928 with jury selection, which took less than one day to complete. Late that afternoon a jury of 12 men, plus two alternates, was impaneled and sworn in. Defense Attorney Dore filed a motion to suppress all the material evidence, which he claimed had been seized illegally. Judge Steinert said he would rule on the individual items if and when they were offered into evidence.

On Thursday morning, Prosecuting Attorney Colvin presented his opening statement before a packed courtroom. During his two-hour monologue, he carefully outlined the state's complicated chain of circumstantial evidence against the defendants. Defense Counsel Agnew stated briefly the prosecution had no victim to prove larceny had taken place, and therefore had no case. The defense planned to call no witnesses. He allowed that, although Bassett appeared to be missing, he had voluntarily sold his automobile to Mayer, as evidenced by a notarized bill-of-sale, and his clients were not involved in his subsequent disappearance.

Over the next several days, the prosecution called 71 witnesses to testify and on Thursday afternoon, December 13, rested its case. Prosecutor Colvin then informed the court that he intended to file a habitual criminal charge against defendant Mayer if he was convicted of grand larceny. Defense Counsel Agnew immediately moved for directed verdicts of not guilty on behalf of the defendants, charging insufficient evidence to support larceny convictions. On Friday morning, Judge Steinert denied the defense motion and ruled the state had produced enough circumstantial evidence to warrant sending the case to the jury. When Agnew advised the court he had no witnesses to present, Judge Steinert proceeded with instructions to the jury and final arguments.

Prosecutor Colvin spoke for an hour and a half, during which he reviewed the evidence proving the defendants' scheme to steal Bassett's automobile and personal effects and made an impassioned plea for a verdict of guilty. Defense Attorney Agnew argued the state had failed utterly to establish the corpus delicti (body of the crime). He declared the state had presented no hard evidence that larceny had been committed or established venue in King County. The case was based entirely on weak, totally circumstantial evidence and urged the jury to vote for an acquittal.

The trial concluded late Friday afternoon, December 14, and the case went to the jury at 5:30 p.m. After deliberating for less than two hours, including 90 minutes for dinner, the bailiff notified Judge Steinert the jury had reached a verdict. Court was reconvened and jury foreman Henry F. Dailey announced that Mayer and Smith had been each found guilty of two counts of grand larceny. Later, a juror remarked to a reporter that a verdict could have been reached earlier, but his colleagues wanted "one more good dinner on the state of Washington" (The Seattle Times).

On Friday, January 11, 1929, Prosecutor Colvin charged Mayer in Superior Court with violation of the state's Habitual Criminal Act (three felony convictions, including one in Washington state) making him eligible for a life sentence. That afternoon, Mayer appeared before Judge Adam Beeler (1882-1947) and entered a plea of not guilty.

The trial was held on Wednesday, January 30, before King County Superior Court Judge Malcolm Douglas and lasted just one day. The first 12 jurors were accepted without challenge and both the prosecution and defense waived opening statements. Prosecutor Colvin called just four witnesses who introduced evidence regarding Mayer's felony convictions in Montana, Utah, Colorado, and Washington. Defense Attorney Agnew neither cross examined any of the witnesses nor presented a defense and the case rested at 11:26 a.m. In his closing statement, Agnew admitted that, under the evidence presented by the prosecution, the jury had no option but to find his client guilty. After only 20 minutes deliberation, the jury returned a verdict of guilty. Tersely denying a defense motion for a new trial, Judge Douglas immediately pronounced sentence: life imprisonment without parole in the Washington State Penitentiary. Mayer was transported to the prison, under heavy guard, on Sunday, February 18, 1929.

On Thursday, February 7, 1929, Mary E. Smith appeared before Judge Steinert and was sentenced to serve from five to 10 years in the Washington State Penitentiary. Defense Attorney Agnew advised the court that Smith had decided to appeal to the Washington State Supreme Court for a new trial. Pending her appeal, Judge Steinert ordered Smith be held in the county jail and set bond at $25,000.

When Mayer, who had initially declined to appeal, realized an overturned conviction would negate his life sentence, he wrote to Attorney Agnew from the penitentiary, asking him to appeal his conviction to the State Supreme Court. The appeal was filed on March 14. On Sunday, May 12, 1929, Mayer was returned to the King County Jail to await the Supreme Court's ruling. Defense Counsel Agnew argued both appeals on October 16, 1929, charging 11 assignments of error by Judge Steinert and insufficient evidence to prove larceny. The justices took the case under advisement, with the issuance of a ruling at a later date.

Harsh Interrogation Techniques

Beginning on November 14, Prosecutor Colvin and King County Sheriff Claude G. Bannick decided they would find Bassett's body, no matter what the legal consequences. Mayer was subjected to six days of limited sleep, chloroform masks, injections of "truth serum" (scopolamine), long hours of questioning with the "lie detector" (polygraph), and wearing an Oregon boot (an iron shackle, weighing between five and 28 pounds, that locked around the prisoner's ankle). Smith was only subjected to questioning with the "lie detector" and injections with "truth serum." Finally, Mayer asked to speak with Colvin in private. When everyone had left the room, Mayer admitted the murder, saying he knew the confession couldn't be used against him and agreed to show Colvin and Bannick the general area where Bassett's body was buried. But the field trip never occurred and Mayer later recanted the confession.

The following morning, November 21, 1929, Defense Attorney Agnew filed an injunction in King County Superior Court, prohibiting further use of torture, "truth serum" or "lie detectors" on either Mayer or Smith. Agnew asserted, and Judge Malcolm Douglas concurred, the draconian methods were a clear violation of the defendants' constitutional rights against cruel and unusual punishment. Prosecutor Colvin argued that the purpose was not to obtain a legally admissible confession, but to discover where the defendants had hidden Bassett's body. Judge Douglas, however, issued a restraining order prohibiting anyone from further questioning the defendants, unless in the presence of their attorney.

On Monday, December 17, 1929, the Washington State Supreme Court affirmed Mayer's grand larceny conviction, but reversed Smith's, based on a technicality, and granted her a new trial. Defense Attorney Agnew filed a petition for a rehearing, stating the tribunal had neglected to comment on the important issue of venue, i.e. whether the prosecution had proved the larceny had taken place in King County and had jurisdiction. On March 27, 1930, the State Supreme Court denied the appeal and ordered Mayer returned to prison. Since there were no questions of constitutionality, Agnew decided an appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court wasn't feasible. On Thursday morning, April 3, Mayer was transported back to the Washington State Penitentiary to continue serving his life sentence.

Retrial of Mary Smith

The retrial of Mary E. Smith, began on Monday, April 21, 1930 before King County Superior Court Judge Edwin Heiman Guie and, in only one hour, a jury of four women and eight men, plus one alternate, was impaneled and sworn in. In opening statements, Prosecutor Colvin contended a conspiracy existed between Smith and Mayer, her alleged son, convicted of grand larceny and now serving life in prison as a habitual criminal, to rob unsuspecting victims of their automobiles. He detailed their scheme and spoke about witness testimony that would substantiate the allegations. Attorney Agnew argued Smith was not her son's accomplice and knew nothing about his criminal activities. If there was a crime, it was committed by Mayer alone, without her knowledge or assistance. Smith only knew he came home with a blue roadster on September 5, 1928 and told her he paid $1,600 cash for it. She never suspected any wrongdoing in connection with the car and was astounded when they were arrested in Oakland for Bassett's murder.

The prosecution rested on Friday, April 25, and on Saturday morning, Attorney Agnew put Smith on the witness stand to testify on her own behalf. After several preliminary questions, he attempted to set the stage for testimony that the defendant was mentally ill as the result being subjected to injections of "truth serum" and prolonged questioning with the "lie detector." Prosecutor Colvin objected and a long, heated argument ensued during which he accused the defense of attempting to create a smoke screen to obscure the real issues of the trial. Judge Guie sustained the objection and had all of her testimony relating to "truth serum" and "lie detectors" stricken from the record. After more ineffective witnesses, the defense rested its case.

The trial concluded late Saturday afternoon, April 26, and the case went to the jury at 5:22 p.m. After deliberating for two hours and five minutes, including dinner, the bailiff notified Judge Guie the jury had reached a verdict. Court was reconvened and jury foreman announced that Smith had again been found guilty of two counts of grand larceny. On Monday, April 28, Judge Guie sentenced Smith to serve from five to eight-and-a-half years at the Washington State Penitentiary. Agnew filed another appeal to the State Supreme Court, but it was dismissed September 19, 1930. On Thursday, October 16, Smith was transported to the penitentiary at Walla Walla to begin serving her sentence.

Confessing to the Killing

In 1929, Gene Bassett's automobile, which had been given to Attorney Agnew by his clients as a fee, was turned over to his father, Frank P. Bassett, who sold it through a Chrysler dealership in Seattle. Edwin D. Colvin remained in office through 1930 and vowed the search for Bassett's body would continue indefinitely. But with the case finally over, media interest waned and tips from the public dried up. In 1931, Robert M. Burgunder replaced Colvin as King County Prosecutor. Admitting there was virtually no hope of finding Bassett's body, Burgunder withdrew the watch, wallet, belt and cufflinks from the exhibits filed with the Superior Court and sent them to Gene's parents, Frank P. and Marion F. Bassett, in Annapolis, Maryland, as keepsakes.

The case was mostly forgotten until May 1938 when Mary E. Smith, just prior to being released from the penitentiary, confessed to the Bassett homicide. King County Prosecutor B. Gray Warner charged Mayer and Smith with first-degree murder.