The creation of the Port of Seattle on September 5, 1911, was the culmination of a long struggle for control of Seattle's waterfront and harbor, a struggle whose roots stretched all the way back to the city's founding 60 years earlier. Seattle had grown from a tiny frontier settlement to a bustling trade center due in large part to the transcontinental rail lines and transoceanic water routes that met along its central waterfront. But the railroad corporations that helped spur Seattle's growth also dominated its waterfront, physically and economically. Their tangle of tracks and trains along the aptly named Railroad Avenue separated the city from its harbor. The rail companies also owned most of the docks and warehouses, so they exercised a stranglehold over Seattle's trade. With competing firms each pursuing its own self-interest, coordinated harbor improvements were impossible to achieve. For more than 20 years, reformers sought to end the railroad stranglehold, and modernize and rationalize Seattle's harbor, by establishing publicly owned and operated port facilities.

Building into the Bay

The problems facing the waterfront that inspired calls for a public port were rooted in both the natural history of Elliott Bay and the human history of the young city on the bay's eastern shore. Seattle was a commercial port city from its founding in 1851. In Elliott Bay, Seattle had one of the world's great deepwater ports, a large protected harbor in which even the biggest ships could anchor close to shore. But, before the massive regrading that created today's waterfront, that shore climbed sharply from the water's edge with little adjacent dry flat land for commercial or industrial development.

As a result, Seattle's commercial waterfront, beginning with Henry Yesler's (1810-1892) lumber mill and wharf, was built on piers extending into the bay. In 1876, Front Street (now 1st Avenue), the main business street running north from Yesler's Wharf, was graded and filled behind a wooden bulkhead above the beach, from which small docks stretched out into the bay. By the 1880s, new streets -- Post Alley and Western Avenue -- were being built beyond Front Street on fill and pilings over the tide flats.

When railroad tracks reached Seattle in the 1870s, they too were built on piers and trestles over the water. This was in part due to physical necessity, but the many railroad trestles also reflected the history of Seattle's off-and-on courtship with and by transcontinental railroad lines. In 1873, the Northern Pacific, the first transcontinental line to reach the Northwest, spurned Seattle, choosing the upstart town of Tacoma, 30 miles south on Puget Sound, as its Western terminus.

Seattle was able to prosper despite this slight because its existing development, excellent harbor, and central position on Puget Sound made it the logical home port for the "Mosquito Fleet" of small steamships, and thus the center of regional commerce in lumber, coal, produce, manufactured goods, and other cargo. Still, Seattle civic leaders wanted a railroad and decided to build their own. The local line never made it farther east than the coalfields of Renton and Newcastle, but it did set a precedent: Its tracks reached King Street from the south via a trestle across the tidelands.

Several years later, the local owners sold their railroad to Henry Villard (1835-1900), who raised the city’s hopes when he acquired control of the Northern Pacific in 1881 and promised to bring the transcontinental line to Seattle. In return, Villard requested a right-of-way along the central waterfront, which the city happily granted. Villard brought the promised branch line to Seattle, but when he lost control of the Northern Pacific in 1884, new management all but abandoned the Seattle link in favor of Tacoma.

Railroad Avenue

In response, a new local railroad effort was organized the following year by Judge Thomas Burke (1849-1925), a lawyer and real-estate speculator who was one of Seattle's wealthiest and most influential citizens. It was Burke who conceived Railroad Avenue. In order to outflank the Northern Pacific, which controlled the waterfront right-of-way, Burke prevailed on a sympathetic city council to dedicate a new 120-foot-wide "street" (it would later expand) over the tidewater beyond the existing waterfront, and grant his line a 30-foot right-of-way along this street. This action was legally questionable because, while Washington was a territory, the federal government held title to all tidelands. But there was ample precedent for private use of tidelands in the many docks and buildings constructed on pilings and in the earlier railroad rights-of-way.

Railroad Avenue began taking physical shape in April 1887, when the first of 26,000 piles, cut in nearby forests, were driven into the Elliott Bay muck. The first trestle, then just one track wide, was finished later that year. In 1889, Seattle's great fire destroyed part of this original Railroad Avenue. The trestle-borne avenue was one of the first things rebuilt after the fire, and it was broadened and extended, as were Western Avenue and Post Alley lying between it and dry land. In 1890, Burke's Railroad Avenue right-of-way fell into the hands of the Northern Pacific, but by then the company had curtailed its efforts to quash Seattle.

The city was now being wooed by another transcontinental line -- the Great Northern Railway that James J. Hill (1838-1916) was pushing across the northernmost tier of the United States. Seattle's location, harbor, and commercial development made it a logical place for the Great Northern's terminus, and Hill had the good sense to engage the persuasive and influential Thomas Burke as his local agent. Having previously achieved the creation of Railroad Avenue, Burke had little difficulty persuading the city council -- over the vociferous objections of the Northern Pacific -- to give the Great Northern a 60-foot right-of-way down the middle of the wood-planked roadway.

Growing Pains

The Great Northern reached Seattle in 1893, and by 1895 there were four transcontinental rail lines jostling for position on the waterfront. Seattle finally had its continental connections and a rapidly burgeoning international trade. Japan's Nippon Yusen Kaisha shipping line contracted with the Great Northern in 1896 to begin regular steamship service between Seattle and Japan. Hill soon launched his own ocean liners, the Minnesota and the Dakota, which carried passengers and goods from Smith Cove to China, Japan, and the Philippines.

In addition to its growing Asian trade, Seattle already dominated trade with Alaska, and it was at Seattle’s waterfront that the steamer Portland docked in 1897 with the fabled "ton of gold" that ignited the Klondike Gold Rush. Seattle became the primary jumping-off point for gold seekers hurrying to Alaska and Canada in search of instant wealth, boosting the city’s economy and population to new highs. The gold rush put Seattle on the national map and pumped money into local businesses as both the hordes of would-be millionaires heading north, and the few who actually struck it rich returning home, spent much of their money in the city. In the first few years of the 1900s, private rail and dock owners built new wharves and terminals along the waterfront at a rapid pace. But despite the economic benefits, this uncoordinated development did not improve, and in some cases exacerbated, the tangled and dangerous mess that the central waterfront had become.

Long before the gold-fueled boom, some voices were proposing a different vision for Seattle's waterfront, calling for greater public control, even ownership, of harbor facilities. Many of these voices, especially at first, were part of the national Progressive movement, which was particularly strong in Washington and which advocated public control of essential services. Reformers worked on multiple fronts, and there were long struggles for greater regulation of the railroads and for municipal ownership of water and electric utilities (Seattle would become one of the first cities in the country to create city water and electric departments). In Washington, with its many port cities and strong dependence on trade, the battle for public control of the waterfront was especially contentious.

"A Blot on the City"

As early as 1890, prominent engineer and municipal planner Virgil G. Bogue (1846-1916) argued that all harbors in the state should be publicly owned. In an 1895 proposal for coordinated waterfront development, Bogue described the existing condition of Railroad Avenue, separating downtown and the docks "with trains frequently passing, switching going on, and cars and trains standing on the various tracks," as "an exceptional state of affairs scarcely equaled elsewhere" and "a blot on the city and a menace to the lives of its people" (Post-Intelligencer). Citing successful ports elsewhere, Bogue asserted:

"The greatest commercial success has resulted where there has been, either in part or in whole, municipal or other public ownership and control of dock frontage" (Post-Intelligencer).

Bogue proposed a single terminal company to control and coordinate waterfront facilities. His plan won support from some rail lines, but opposition from the Great Northern doomed the plan. Nevertheless, the contrast between the efficient new port envisioned by Bogue and the existing waterfront chaos helped convince more Seattle leaders that a public body was needed to modernize the waterfront.

In 1896, reformers briefly banded together in the short-lived Populist Party to capture the state legislature and the governor's mansion. The party fell apart before accomplishing much, but the state lands commissioner it elected, Robert Bridges (1861-1921), went on to play a critical role as one of the Port of Seattle's first commissioners. After the Populist Party imploded, the reform banner was picked up by the Progressives, who operated mostly within the existing Republican and Democratic parties. Along with municipal ownership, Progressives advocated for labor rights, woman suffrage, and prohibition. In turn, both unions and woman suffrage organizations were strong backers of municipal ownership. Not surprisingly, the longshoremen who worked the docks were especially interested in promoting public control of waterfront areas, both to create more shipping and therefore jobs and to provide a counterweight to the strength of private employers.

Progressive Engineers

In Seattle, civil engineers were among the leading Progressives. In addition to Bogue there were City Engineer Reginald H. Thomson (1856-1949), who built Seattle's Cedar River water and power systems and leveled various in-town hills in massive regrading projects, and George F. Cotterill (1865-1958), Thomson's one-time assistant who went on to draft legislation creating public ports and to serve four terms on the Seattle Port Commission.

Thomson argued successfully against James J. Hill's proposal for a massive Great Northern terminal on the central waterfront. Thomson foresaw that it would interfere with creating new industrial land south of downtown on the tidelands near the mouth of the Duwamish River (land that ultimately would become a major part of the Port of Seattle) and eventually persuaded Hill to bring the Great Northern tracks under downtown in a tunnel. The tunnel (still used today) did not eliminate waterfront congestion but helped keep it from worsening.

Cotterill combined engineering work with political activity. In 1907, as chairman of the state Senate Committee on Harbors and Harbor Lines, he drafted the first bill to authorize public ports in Washington, which would have created port districts with limited powers. In addition to those calling for public control of Seattle's harbor, the bill won support from many around the state who believed public port facilities could benefit their communities. However, Governor Albert E. Mead (1861-1909) vetoed the 1907 bill, and proposed legislation failed again in 1909, blocked by railroad interests and mill owners.

Canal Visions

By the end of the decade, railroad obstruction of public harbor improvements in Seattle was driving even conservative business leaders and politicians, along with the city's two major newspapers, the Seattle Post-Intelligencer and The Seattle Times -- all generally opposed to municipal ownership -- to support the concept of a public port. Two long-anticipated canal projects, one local and one international, played central roles in the growing consensus that Seattle needed a public port authority.

Locally, almost from the time the city was founded, Seattleites dreamed of a canal connecting Elliott Bay to Lake Washington, the large freshwater lake on the city's eastern side. The ship canal became a reality after General Hiram M. Chittenden (1858-1917), yet another dynamic and progressive civil engineer who would leave his mark on the city and Port of Seattle, took charge of the federal Army Corps of Engineers Seattle district office in 1906. Congress soon provided funding for the locks that would be necessary (and that were eventually named in honor of Chittenden), on the condition that local funds pay for the canal itself.

In addition to building their own canal, Seattle civic leaders wanted to ready the harbor for the opening of the Panama Canal, which they (and their counterparts in cities up and down the West Coast) anticipated would bring large increases in waterborne trade with the Eastern Seaboard and Europe. Because the shorter water route through the canal would not increase train cargo (indeed, it meant competition for the transcontinental lines), the rail corporations that owned Seattle's waterfront had little incentive to prepare for more intercoastal shipping.

Seattle leaders feared the city would fall behind rival Western ports that were already investing in docks and wharves to attract the expected new shipping. Even Tacoma, which had long lagged behind its neighbor in maritime trade, was catching up, and in 1910 began building Washington's first municipally owned dock. The Seattle Times, despite its general opposition to municipal ownership, editorialized that Seattle should also "determine this question of city-owned docks in the affirmative" (Woodward). With railroads in control of the central waterfront, proponents of new public facilities looked to the undeveloped land along the Duwamish River.

In 1909, the legislature, even as it rejected public port legislation, authorized King County voters to establish separate local improvement districts that could issue bonds and levy taxes to build the Lake Washington Ship Canal and develop the lower Duwamish into a waterway for large oceangoing ships. The King County commissioners approved a combined $1.75 million bond issue for the two projects, and two future port commissioners -- Robert Bridges, the Populist firebrand, and Charles E. Remsberg, a Fremont banker, attorney, and real-estate speculator -- headed the campaign for the bond issue, which won easily in the November 1910 election.

The Port District Act

Railroad attorneys immediately sued to invalidate the local improvement districts and managed to block work on the Duwamish Waterway for a time, but this latest attempt to obstruct projects that much of Seattle's commercial and business establishment considered essential was the last straw. When the 1911 legislative session opened, a broad consensus favored creating public port districts in Washington, as Governor Marion E. Hay (1865-1933) recognized:

"The people of this state are in favor of public docks and wharves and such harbor improvements as will aid commerce and navigation for the benefit of all" (1911 Senate Journal).

The legislature passed the Port District Act, which Governor Hay signed into law on March 14, 1911. Drafted by Cotterill, Thomson, and Seattle Corporation Counsel Scott Calhoun, the Port District Act authorized Washington voters to create public port districts that could acquire, construct, and operate waterways, docks, wharves, and other harbor improvements; rail and water transfer and terminal facilities; and ferry systems. A port district would be a government body, run by three elected commissioners, independent of any existing county, city, or other government, with the power to levy taxes and issue bonds.

Forming the Port

Even before the Port District Act took effect on June 8, 1911, Calhoun and the Seattle Commercial Club organized an ad hoc committee, with representatives from the Seattle Chamber of Commerce, Municipal League, Rotary Club, Manufacturers' Association, and other groups, to form a port district in King County. As soon as the act was law, the committee quickly collected the signatures needed to place creation of the Port of Seattle on the county’s September 5 ballot.

Recognizing that a public port would be of little use if the railroads and private dock owners dominated the Port Commission, Calhoun's committee also screened potential candidates for the three commissioner positions, endorsing three at a July 28 meeting. For the central district, the committee selected Hiram Chittenden, the well-respected former Army Corps of Engineers officer. The committee's choice for the south district was the combative former state Lands Commissioner Robert Bridges. Charles Remsberg, the Republican banker from Fremont chosen for the north district, was supposed to balance the Populist Bridges on the ticket, but he was as committed to municipal ownership as his fellow nominees.

With support from the press, civic organizations, politicians, and most of the business community, the proposition to create the Port of Seattle passed on September 5, 1911, by a wide margin, 13,771 votes to 4,538. Chittenden more than doubled his opponent's votes, while Bridges and Remsberg won by lesser but still substantial margins.

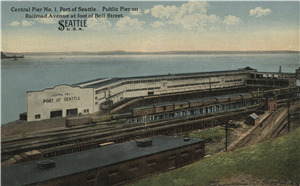

One week later on September 12, 1911, the new commissioners met for the first time and began planning and developing Seattle's first public harbor facilities, which would include Fishermen's Terminal on Salmon Bay, two huge piers at Smith Cove, and the original Bell Street Pier. Over the next 100 years, they and their successors built the Port into a leading container terminal; developed and operated Seattle-Tacoma International Airport, the region's largest; and created the many other facilities that make the Port of Seattle a major contributor to economic growth.