The Port of Tacoma is a public municipal corporation governed by five elected port commissioners. Pierce County voters created the Port in 1918 after the 1911 state legislature authorized publicly owned and managed port districts. Ninety years later, the Port of Tacoma is a leading container port, serving as a "Pacific Gateway" for trade between Asia and the central and eastern United States as well as the Northwest. The vast majority of trade between Alaska and the lower 48 states also passes through Tacoma. Part 1 of this Thumbnail History of the Port traces its development from Tacoma's early maritime commerce through World War II. Until 1918, Tacoma's waterfront was dominated by private entrepreneurs and corporations, especially the Northern Pacific railroad. After longshore workers, Tacoma business leaders, Pierce County farmers, and others united to establish the public port, its Commissioners built two piers that handled an increasing volume of trade from around the world, a cold storage plant, and a grain elevator. The Depression slowed growth, but World War II brought new activity and increased mechanization to Port of Tacoma docks.

Sawmills and Railroads

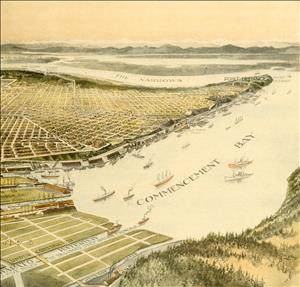

The transformation of a pioneer sawmill village on the shore of Commencement Bay to the world-class Port of Tacoma has spanned 140 years. Swedish immigrant Nicholas Delin (1817-1882) took the first step in 1852 when he constructed a water-powered sawmill at the present juncture of Dock Street and Puyallup Avenue. It took six months to saw and load 350,000 board feet of squared timbers destined for San Francisco lumberyards. After observing the deep harbor and virgin forests, Charles Hanson, a Danish sea captain turned California mill owner, constructed a steam sawmill and the Starr Street wharf in 1868. Mill crews and lumber handlers cut and loaded the first cargo of 425,000 board feet of fencing on the bark Samoset in 28 days. The Hanson & Company mill inaugurated Tacoma's maritime trade with foreign nations during the fall of 1871. Five French deep-water ships carried special dimension lumber to Callao, the chief port of Peru. On January 16, 1872, the Good Hope sailed with the first cargo purchased by Melbourne, Australia, lumber dealers.

The Northern Pacific (NP) bought Hanson's mill along with two miles of deep-water waterfront and 600 acres of tideflats in 1873. When the first train pulled into Tacoma late that year, the NP had constructed a 350-foot wharf and a freight warehouse beside its half moon rail yard. The Northern Pacific built a spur line to its Wilkeson coal mines. In 1883 the railroad line completed a 528-foot railroad trestle from its wharf to two large offshore coal bunkers. Coal exports rose to a high of 633,979 tons in 1901 and thereafter declined as oil replaced coal as the major source of energy for West Coast industries.

The 1880s proved to be a boom decade for Tacoma. The population rose from 1,098 in 1880 to 36,006 in 1890. The Pacific Coast Steamship Company started regular freight, passenger, and mail service between San Francisco, Puget Sound, and Alaska ports in August 1880. Every 10 days a Pacific Steam vessel tied up at the Northern Pacific wharf in Tacoma to discharge general cargo and load coal, lumber, or hops. From 15th Street to the Point Defiance smelter, entrepreneurs erected five wharves, 16 sawmills and shingle mills, three brickyards, and the longest warehouse in the world. A giant steam dredge dug a channel through the tideflats to create the City Waterway. On top of the dried mud, workers secured a planked roadway and City fathers named it Dock Street.

Trade With Asia

In 1885, tea importer Fraser & Company gave the Northern Pacific the contract to handle the Japanese tea fleet. Dozens of Tacomans waited until 3 o'clock in the morning on August 7, 1885, to greet the Isabel with its cargo of 22,475 tea chests. Shipping the tea to New York, 3,378 miles away, took 192 hours. California's Southern Pacific Railroad beat out Tacoma for the 1886 Fraser & Company contract, but the following year Tacoma became the permanent receiving port for the tea fleet. Costs of stevedoring and towing to Tacoma averaged 10 percent less than San Francisco. In sailing time, Tacoma had proven to be five days shorter to Yokohama than the Bay City. From 1887 through 1892, 16 ships from Japan and China called at Commencement Bay carrying 37 million pounds of tea. Spurred by the tea trade, additional Asian ships brought loads of straw goods, rice, and silk.

In the midst of the economic boom, waterfront employers and workers had their first falling out. On March 22, 1886, Tacoma longshoremen demanded a raise from 30 to 40 cents an hour and that employers hire only members of their new union, the Stevedores, Longshoremen and Riggers Union of Puget Sound. After five days of aggressive bargaining, Rudolph DeLion, head of the Port Townsend-based Delion Stevedoring Company, acceded to the workers' terms. The new longshore union, and all succeeding Tacoma waterfront locals, kept the membership book open to workers of all races. Eleven times the Tacoma longshore unions have struck, either for recognition, shorter hours, higher wages, or safer working conditions.

Growing Volume

On June 6, 1887, the Northern Pacific finished the Cascade Division, opening the way for Eastern Washington wheat to move directly to Tacoma. At the same time construction crews finished three grain elevators near the Northern Pacific wharf. Wheat exports grew gradually until 1902, the year Tacoma surpassed Portland in volume, shipping 11,363, 896 bushels on 111 ships. Ex-longshoreman William L. McCabe, head of the Puget Sound Stevedoring Company, invented a motorized conveyor belt that carried 30,000 wheat sacks into the hold during a 24-hour day. In the hold 14 men took turns catching the 180-pound sacks on their shoulders as the bags came down the belt. The wheat packers ran at a turkey-trot pace to the place where they lowered the bag into a niche. Wheat packers received 35 cents an hour and worked a 10-hour day.

The most famous resident of the Tacoma waterfront in 1889 was a blonde Norwegian bride named Thea Foss. She bought a rowboat for $5 from a disgruntled fisherman and sold it within days for $15. She parleyed that small start into a tugboat empire. Her husband Andrew built boats and Thea rented them out to weekend fishermen and to anyone who needed transportation around the harbor.

Hard Times

During the early 1890s, thousands of banks and businesses throughout the world declared bankruptcy and closed their doors. Tacoma thought it had avoided the economic depression until a whispering campaign on a Sunday and four days of heavy withdrawals forced the Tacoma Merchants' National Bank to close on June 1, 1893. Within a year 13 more banks in Tacoma had failed, leaving only seven still in business. When the Northern Pacific Railroad declared bankruptcy and Pacific Coast Steam went into receivership, Tacoma's economic life practically stopped.

By the time the depression ended in 1897, the restructured Northern Pacific had moved its headquarters to Seattle. The Queen City had also gained control of the Alaskan maritime trade. But Tacoma still had the lion's share of the coal, flour, wheat, and lumber trade with Asia, Europe and South America. Lumber emerged as Tacoma's Number One export. In 1907, Tacoma's 135 lumber handlers stowed 202,559,628 board feet, a record that has never been equaled. Throughout the world Tacoma became known as "The Lumber Capital of the World." The 22 sawmills on Commencement Bay were working 24 hours a day, seven days a week.

During the fall of 1907 another economic panic struck nationwide. This time coaster and international steamship lines fought a seven-year freight-rate war that no one won. Coupled with the rate war was a prolonged decline in the world's demand for American wheat, lumber, and coal. Everywhere on the West Coast wages of steady longshoremen were cut to 30 cents an hour. Boss stevedores hired unemployed workers for even less at the dock gates. A few Western Washington longshoremen joined the Industrial Workers of the World, "the Wobblies," who advocated direct action to solve the problem of hard times.

Promoting a Public Port

Other longshoremen sought to use the political process to reform the waterfront. Since the 1890s, workers had supported legislative efforts to increase public control of waterfront areas. After several defeats, those efforts bore fruit in 1911, when the Washington State Legislature passed the Port District Act, which enabled counties to establish public port districts. To educate Pierce County voters on the possibilities of a public Port of Tacoma, the city council hired Virgil G. Bogue (1846-1916) to design a plan for the development of Commencement Bay. The heart of the Bogue Plan was the creation of a Wapato-Hylebos Waterway with turning basins connected to industrial plants, railroads, warehouses, and highways. The first vote on November 5, 1912, to establish a Port of Tacoma failed by 395 votes out of 20,767 cast. The defeat was the result of rural Pierce County citizens believing the port would benefit only urban Tacoma business people.

World War I interrupted the campaign to create a public Port of Tacoma. Tonnage surged from 1,260,645 tons in 1914 to 2,909,530 in 1917. It was the heyday of private enterprise on the waterfront. Entrepreneurs operated wood-processing plants, flour mills, electro-metallurgy factories, electro-chemical installations, and above all shipbuilding companies. The needs of the new shipyards in Tacoma, Seattle, and Portland created a huge labor shortage. West Coast waterfront workers struck as a unit in 1916 demanding higher wages, but after 127 days Tacoma general cargo workers returned to work at the old wage scale. After the United States entered the war, the federal government took complete control of waterfront hiring in Tacoma. Within six months federal officials had turned over control of dispatch of jobs to longshore leader Jack Bjorklund.

When the public Port of Seattle contracted to outfit the United States Army's expedition to Siberia in August 1918, the Tacoma waterfront community renewed its campaign to create a public port in Pierce County. W. H. Paulhamus, a state senator and president of the Puyallup and Sumner Fruit Growers' Canning Company, gained rural support by arguing that a public port could build a cold-storage building on the waterfront, making it easier for farmers to preserve and ship their produce. Businessmen, including the president of the Pacific Steamship Company, and the Tacoma Daily Ledger supported the measure. Longshoremen also played a leading role, with union members doorbelling Pierce County voters to gain support for the measure.

Open for Business

The proposition creating the publicly owned Port of Tacoma passed on November 5, 1918, by a vote of 15,054 to 3,429. In the same vote, longshoreman Edward Kloss, Sumner fruit and dairy farmer Charles W. Orton, and banker Chester Thorne were chosen as port commissioners. The new port commission hired Engineer Frank J. Walsh to create a master plan for the development of the Port of Tacoma. Walsh recommended that the port's first two piers should be on the Middle Waterway, the area now occupied by the Simpson Paper Company. In May 1919, voters approved Walsh's master plan and a $2.5 million bond issue to fund land purchase and construction. Tacoma Dredging Company was awarded the contract to build the 800-foot-long Pier 1.

The Port of Tacoma formally began commercial shipping on March 25, 1921, at Pier 1. Fifty lumber handlers loaded 600,000 board feet on the Edmore in 24 hours, a world record. Port business grew so quickly that within a year the commissioners approved a 300-foot extension of Pier 1 to provide additional space for ships and cargo. The Port bought a new five-ton hammerhead crane with a 90-foot boom for the pier. By 1923 Pier 2, with its huge bulk storage transit shed, had been completed. The Pier 2 warehouse employed a unique overhead monorail crane system that moved cargo from ship to warehouse more quickly. Dockside rail tracks at Pier 2 allowed for direct transfer between ships and railroad cars.

The 1920s were good years for the Port of Tacoma. Tonnage increased from 3,254,035 in 1922 to 6,405,759 in 1929. By the end of the decade, at least 25 steamship lines, including six from Europe, five from Asia, and four from South America, along with American lines based on the Atlantic, Gulf, and Pacific coasts and in Puget Sound, all made regularly scheduled stops in Tacoma.

Port Development

The Port undertook several other initiatives during the 1920s. The commissioners granted a 30-year lease of harbor land in Ruston, north of downtown Tacoma, to the American Smelters Securities Company to allow for expansion of the copper smelter that opened there in 1890. The Ruston smelter, later operated by the American Smelting and Refining Company (ASARCO) was for many years one of the largest employers in Pierce County and also a significant source of pollution.

In 1928, the Hooker Chemical company, one of a number of electrochemical companies attracted by inexpensive electricity from Tacoma Public Utilities, built a plant on the tideflats. The following year, at the urging of Tacoma Chamber of Commerce manager T. A. Stephenson, the Tacoma port commissioners supported the effort by the Port of Seattle to build an airport midway between the two cities. After passage of legislation authorizing the port districts to build and operate an airport, the Port of Tacoma contributed $70,000 to the effort on condition that the airport's name include Tacoma. Seattle-Tacoma International Airport, whose initial construction ended up costing over $4 million, did not open until the 1940s, but thanks to that early contribution (along with an additional $100,000 that Tacoma and Pierce County provided in 1940 to support Sea-Tac's Bow Lake location), Tacoma was and remains part of its name.

The Port of Tacoma Commission worked throughout the decade to build the promised cold-storage plant that had helped win voter approval for the port in 1918. It took 10 years to complete the plans for the highly technical building project. After further delays in bidding and building, the cold-storage plant finally opened in 1931. In the meantime, voters in 1928 approved a bond issue allowing construction of a publicly owned grain elevator that began operation in 1930.

Depression and New Deal

As construction of the cold-storage plant and grain elevator was underway, the Great Depression hit Tacoma's waterfront. In 1930 tonnage dropped 1,446,470 tons below 1929 levels and it fell another 707,702 tons in 1931. From 1931 to 1932 port commissioners had to cut wages for everyone from the general manager to the janitors three separate times. The Port also had to reduce rents for businesses leasing port land. After Franklin D. Roosevelt (1882-1945) became president, Tacoma's maritime commerce quickened. A sign of better times occurred on August 13, 1933, when 11 freighters sailed into Commencement Bay.

Roosevelt's New Deal reforms gave unions more clout than they previously had. When employers refused to collectively bargain with the International Longshoremen's Association (ILA) during the spring of 1934, the longshoremen, joined by other shipping-industry workers, closed down every major port on the West Coast for 85 days. A federal government arbitration panel settled the strike in favor of the longshoremen. Along with wage increases and other gains, the longshore unions won substantial control over hiring decisions. This part of the victory, although significant, did not directly affect the two Tacoma unions, ILA locals 38-3 and 38-30, which were fully closed shop even before the strike, the only large longshore unions on the coast to enjoy that distinction.

The Great Depression stymied Port of Tacoma development until the 1939 state legislature empowered public ports to develop new industrial areas. Tacoma port commissioners created an Industrial Development District and Waterway south of 11th Street between Hylebos Creek and Milwaukee Way. An Industrial Bureau was established to recruit tenants, but World War II interrupted the project.

Wartime Changes

Like so much else, the Tacoma waterfront was largely given over to the military effort from 1942 to 1945. Thousands of troops trained at nearby Fort Lewis were dispatched to the Pacific theater from Port of Tacoma piers. Sacked flour for troops in Hawaii, wool blankets for soldiers in Alaska, and munitions for the armed forces fighting in the Pacific all rolled across the docks. Longshoremen were busier than during the Depression, but not all found full-time work, due in part to the fact that Seattle took the lion's share of the region's army and navy business.

Increased mechanization on the docks was another factor reducing the number of longshore workers needed. With ample resources at its command, the United States military spent freely on new equipment to speed up loading and discharging. Forklifts replaced jitneys for moving cargo from warehouses to docks, allowing the use of pallet boards on which tons of sacks or other cargo could be stacked and lifted aboard ship with new larger cranes. Foreshadowing the container revolution that still lay in the future, the military also introduced the first small containers, known as Conex boxes.

When the war ended in 1945, West Coast cargo trade plummeted 90 percent. The post-war years would bring new challenges and changes to the Port of Tacoma.

To go to Part 2, click "Next Feature"