Seattle-Tacoma International Airport, or Sea-Tac as it commonly called, was developed as a direct response to the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. Military needs limited civilian access to existing airports such as Seattle's Boeing Field and Tacoma's McChord Field, and the federal Civilian Aviation Authority sought a local government to undertake development of a new regional airport. The Port of Seattle accepted the challenge on March 2, 1942. After rejecting creation of a seaplane base on Lake Sammamish, the Port chose Bow Lake in southwest King County for the new airfield. Initial construction was completed in October 1944, but full civilian operation did not commence until dedication of a modern terminal building on July 9, 1949.

Early Seattle-Area Airports

Prior to World War I, just about any level grassy field or calm body of water could serve as an informal “airport” for the aircraft of the day. The first airplane to fly in Seattle was demonstrated by daredevil pilot Charles Hamilton (1881-1913) on March 11, 1910, at Georgetown’s Meadows Racetrack (near the present location of the Museum of Flight). Other early pilots such as Terah Mahoney and Herb Munter (1887-1970) flew floatplanes from Lake Washington or the mouth of the Duwamish River.

Young timber magnate William E. Boeing (1881-1956) took his first flight from Lake Washington on July 4, 1915. He chose the foot of Roanoke Street on Lake Union as the site for the Pacific Aero Club in 1916. There he and his partner, Navy Captain Conrad Westervelt, built their first aircraft, a pair of float planes dubbed the B&W. When America entered World War I in 1917, the Navy ordered an advanced version as a trainer and thereby launched the Boeing Airplane Company. Boeing expanded production by converting his private Duwamish River boatyard (now the famed Plant I “Red Barn,” which was relocated across the river to the Museum of Flight in the early 1980s) into an airplane factory.

In response to defense concerns during World War I, the Navy began scouting Puget Sound for a suitable site on which to establish an airfield, and chose Sand Point on Lake Washington. Army pilots also landed at Seattle’s Jefferson Park municipal golf course during a War Bond drive. Military interest in aviation briefly vanished following the November 11, 1918, Armistice, almost bankrupting the Boeing Company. New airplane orders ultimately arrived from the Army, prompting Boeing to build a primitive landing field next to his Red Barn factory.

Meanwhile, in 1920 King County acquired the Sand Point site previously recommended by Navy surveyors in the expectation that the Navy would quickly take over development of an air station. This in fact took another six years, and the airfield, although useful for Boeing aircraft assembly and testing and for other aviators, became a financial albatross for the County and lost $2.5 million. Bryn Mawr Airfield, now Renton Municipal Airport, on the south shore of Lake Washington, and Tacoma’s Municipal (now McChord) Airfield were also developed in the 1920s. Pan American Airways later developed a seaplane terminal at Matthews Beach, just north of Sand Point.

In 1925, Congress passed the “Kelly Act” which authorized the Post Office to contract with private companies to carry airmail and paying passengers on fixed routes. This was the seed for the modern airline industry, and Boeing’s Chicago-San Francisco airmail franchise was the basis of both its own future airliner development and United Air Lines.

The Navy’s acquisition of Sand Point in 1926 created a new headache by displacing Boeing and other civilian pilots. William Boeing threatened to move his company, already the city’s largest civilian employer, unless the County built a new airport that he could use. Seattle Mayor Bertha K. Landes called development of a public airfield one of the city’s “most urgent and important problems,” and Port of Seattle Commissioner George B. Lamping opined that port authorities were the best suited public agencies for the task (but his colleagues did not agree at the time).

In August 1927, the Seattle Chamber of Commerce recommended development of land south of Georgetown along the Duwamish, including the former Meadows Race Track where Seattleites had seen their first airplane. Charles Lindbergh visited soon after and endorsed development of the 147-acre tract, which was mostly owned by King County. County Commissioner Frank Paul balked at the use of public property for private industrial use, but he was overruled and Boeing Field (aka King County International Airport) was dedicated by its eponym on July 26, 1928. William Boeing, who had already begun building his adjacent Plant 2, said, “This is just about the happiest day of my life.”

War Clogs Existing Airfields

Even before December 7, 1941, construction of growing numbers of B-17 bombers was clogging Boeing Field. Following the Pearl Harbor attack, the military took control of it, Renton’s airport, and Tacoma's McChord Field. This spurred demands for a new airport to serve the greater Seattle area.

On January 6, 1942, the federal Civil Aviation Authority offered $1 million to any local government that would undertake the task of building a new regional airport. After much political hand wringing, the Port of Seattle rose to the challenge.

On February 25, 1942, Port Commission chair Horace Chapman (1871-1950) declared that building the airport "is our duty, and if we can do it, we will." The Chamber of Commerce pledged its support at a mass meeting on March 2, and the Port Commission formally voted to accept the job five days later.

The early favorite for the new airport's location was Lake Sammamish. Seaplanes still dominated commercial Pacific and Alaskan airline routes. The lake offered an attractive base away from busy urban waterways, but its proximity to the Cascades posed serious safety concerns. The other candidate was a tract of rough scrubland at Bow Lake, approximately midway between Seattle and Tacoma on Highway 99. It was the site of a small private airfield, developed by Dean Spencer and George Wolf in 1940. Planners thought it would be relatively fog-free -- despite public warnings that it was, in the words of a neighbor, "one of the foggiest places in the whole state." Tacoma and Pierce County tipped the balance by offering $100,000 to help build the airport at Bow Lake. Given that the field ended up costing more than $4 million, that proved to be quite a bargain.

A New Nest at Bow Lake

The Port of Seattle approved the Bow Lake site on March 30, 1942. Planners surveyed 906.9 acres roughly bounded by South 188th Street on the south, Des Moines Memorial Way on the west, South 160th Street on the north, and Highway 99 on the east. The Port spent $637,019 to acquire the site from 264 individual owners.

The Civil Aviation Authority took charge of actual construction. Crews led by Ray Bishop began detailed surveys on April 18, 1942, for north-south and east-west runways forming a “T” connected by an “X” of taxiways. Surveyors encountered coyotes, deer, an Army machine gun nest, and at least one pair of young lovers while laying out the future airport and taking samples of its sandy soil. The condition of the ground pushed construction bids up to $1.7 million, far over initial estimates. The California-based firms of Minnis & Moody, Vista Construction and Finance, and Johnson, Inc. won the final contract and their crews were on the site by Christmas Eve.

Ground was broken on January 2, 1943, by dignitaries including Governor Arthur Langlie, Congressman (soon to become Senator) Warren G. Magnuson, Seattle Port Commission president Horace Chapman, and Tacoma Port Commission President Fred Marvin. Actual construction proved much harder than turning the ceremonial shovels of earth and ultimately required the excavation of 6.5 million cubic yards of earth to establish a level plateau. When this was finally done, the workers laid 14 miles of pipes and six miles of electrical cable, and Seattle’s Fiorito Brothers poured 450,000 cubic yards of concrete for the runways.

Shortly before the airport’s completion, Boeing president Philip Johnson died of a cerebral hemorrhage on September 14, 1944. The Seattle Port Commission proposed renaming the new field in his memory, but quickly retreated in the face of Tacoma’s strenuous objections. Costs had risen to $4,235,000 by the time the new Seattle-Tacoma Airport was dedicated with ceremonial landing by United Air Lines DC-3 on October 31, 1944.

On May 31, 1945, a Northwest Airlines DC-3 inaugurated transcontinental service when it departed Sea-Tac for New York City. On July 17, Pan Am signed the first lease to build an airline terminal and hangar at Sea-Tac, but this would have to wait. The Army Air Force had taken control of the new Seattle-Tacoma Airport for transshipment of B-29 bombers, two of which would drop the atomic bombs that ended World War II in August 1945.

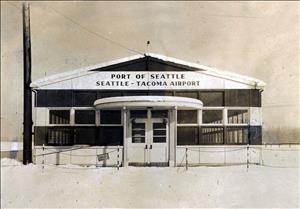

Significant commercial use did not begin until 1946, and passengers had to use a Quonset hut, called “The Pantry,” heated by a single potbellied stove. Port planners recognized that such primitive accommodations would have to be replaced quickly to meet the anticipated post-war surge in air travel. The Port placed a $3 million bond issue on the November 5, 1946, ballot for a new administration building and terminal. Although the bonds won a sizable majority, insufficient voters turned out to validate the election, and the Port had to apply its reserves to the terminal project.

On January 8, 1947, Sea-Tac experienced its first crash when a Pan Am DC-3 overshot the runway, shaking up but not injuring its 17 passengers. A second crash turned out less happily on November 30, 1947. An Alaska Airlines DC-4 charter came in too fast and bounced through buffer lands into the middle of Des Moines Way, and struck a car. The driver survived but not a blind woman riding with him. A flight attendant (stewardess) and seven passengers on the plane also died. The pilot, copilot, and 18 passengers made it out alive.

Meanwhile in 1947, Northwest Airlines and Western Airlines inaugurated the new airport’s first scheduled flights on September 1. One month later, Colonel Earle S. Bigler, a native Kansan who had headed the Chamber of Commerce’s aviation efforts during World War II, took command of Sea-Tac for the Port.

Bigler coordinated design of the new administration building by Herman A. Moldenhour (1880-1976) and Port of Seattle architects. The building was constructed by Lease-Leighland, while Northwest Airlines built a new hangar to service its new “Oriental” runs to the Far East.

Upon completion, the gleaming white building and its soaring control tower and airy, glass-walled concourses were hailed as the state of the art for airport design. Thirty thousand attended the terminal’s dedication on July 9, 1949, dubbed “Conqueror’s Day.” They watched Boeing president William Allen present Northwest Airlines with its first Model 377 Stratocruiser and gawked at the squadrons of military jets and bombers that roared overhead. Governor Arthur Langlie (1900-1966) warned the eagles and the skylarks to move over for "we, too, have won our place in the firmament of heaven." Sea-Tac officially became the Seattle-Tacoma International Airport on that day. The federal government, Port of Seattle, and airlines had by then invested $11 million in the facility, which remains Puget Sound’s aviation gateway to the world.

Next: Part 2, from props to jets (1950-1970)