The City of SeaTac was incorporated in 1989 and named after the Seattle-Tacoma International Airport, which it surrounds. Native Americans had occupied the region roughly midway between present-day Seattle and Tacoma for millennia before the arrival of the first Euro-American settlers in the mid-1850s. The area is centered on the Highline ridge separating Puget Sound and the valley of the Duwamish and Green rivers. The successive construction of Military Road, Des Moines Memorial Way, and Highway 99 (now International Boulevard) fueled the area’s gradual development up to the eve of World War II. The pace quickened with completion of the Seattle-Tacoma International Airport in 1944. Following World War II, as “Sea-Tac” airport quickly became the Puget Sound region’s primary aviation gateway, the area around it grew apace. After much debate, residents adjacent to the airport and in the nearby unincorporated areas of Angle Lake, Manhattan, Sunnydale, Riverton Heights, and Bow Lake voted to incorporate the City of SeaTac (sans hyphen). The city was incorporated on March 14, 1989. City limits embrace 10.5 square miles, including the airport, and more than 25,000 residents, and the community swells with more than 80,000 workers and travelers on an average weekday.

First Peoples

The greater SeaTac area is defined by the Highline (originally “High Line”) ridge, which separates the valley of the Duwamish, White, and Green rivers on the east from Puget Sound on the west. Like the array of generally north-south aligned ridges on the east shore of Puget Sound, Highline owes its elevation to the clay, sand, and gravel left behind by glaciers at the end of the last ice age.

Nearby Angle Lake, Lake Burien, and Bow Lake are small spring-fed lakes that survive from the great melting roughly 12,000 years ago. Native Americans generally inhabited the White/Green River Valley and the shores of Puget Sound rather than the ridge, for the obvious advantages of fishing, farming, and transportation in the lowlands. But especially in the warmer seasons the ridge and its lakes were also used for fishing and snaring waterfowl.

In 1990, William Westlake Walker discovered two submerged dugout canoes, thought to be 200 to 300 years old, while diving in Angle Lake. In a modern recapitulation of ancient territoriality, both the Muckleshoot and Duwamish tribes claimed these exceptional artifacts. Early human habitation of the area was also evidenced by the type of vegetation -- salal and huckleberries -- recorded by federal surveyors as they went through the future site of SeaTac in the 1850s.

Based on such data, local historian David Buerge believes that Indians periodically cleared the land by fire or other means for the cultivation of staples and to attract deer, another important food source. Buerge concludes, “This [area] was not a wilderness, but rather a garden that bore the imprint of human activity for thousands of years.”

The white first settlers arrived in the mid-1850s and generally marked claims close to either the Duwamish River or the Green River (then named the White River) or beside Puget Sound. Land transportation improved significantly in 1860 with the construction of the Military Road to expedite the movement of troops between Fort Steilacoom on southern Puget Sound and Fort Bellingham on the north. The original road ran along the eastern side of present day SeaTac and nearly touched the east shore of Angle Lake. The modern Military Road generally follows the original route.

Life on the Road

From this Military Road the first settlers built their own paths to their homesteads. Following the pattern of sticking close to the river, Jane Fenton and Mike Kelly settled with their families along the then serpentine Duwamish River. As teenagers in the 1860s they went to school together in the Foster and Riverton area. In 1869, the 19-year-old, redheaded Mike explored the nearby “High Line” ridge, an adventure noted in his future wife’s journal:

“Mike took our dog and his gun and struggled up the western hillside. What a surprise he got when he finally reached the top and found a beautiful valley with two streams, huge trees, and fertile land. Right then and there he named it Sunnydale. He posted his intention to homestead by putting a stake in the ground and then hurried home to tell about the treasure he found.”

After Mike and Jane married in 1872, they filed a claim for their Sunnydale land. Also in 1872, Mike Kelly got a permit to build a road between the future South Park (a Duwamish River farming community now part of Seattle) and his claim. With the help of relatives and a team of horses, he began to build what soon became known as the Kelly Road. Their first baby was three weeks old when the couple used the new road to move to their new Sunnydale log cabin in April 1873.

In their log cabin kitchen, the Kellys founded the first school in the future SeaTac. Jane was the teacher and her two kids and a couple of neighbor’s kids the student body. Later, a community of small farms developed around the Kelly spread, and the locals built a schoolhouse beside Miller Creek. The teachers -- almost always young women and by requirement unmarried -- were paid extra to make a fire in the morning. The water came from the creek. Bob Gilbert, age 94, a graduate of that first Sunnydale schoolhouse, remembers that it was he and the other boys who made the daily treks to replenish the cisterns.

Second Wave

A second wave of area-wide settlement began with the completion of the first transcontinental railroad to Puget Sound -- the Northern Pacific -- in 1883, but became a sustained tide of development in the late 1890s. Military and Kelly roads also attracted other settlers to mark claims and develop homes and farms serving the hungry markets of Seattle. By the turn of the century most of the area’s farmers were Japanese immigrants or their children.

Laif Hamilton purchased the Kelly homestead and arranged to have the Kelly Road paved with red bricks. Notoriously slippery when wet, the bricks were also likely to heave up in hot weather. Popularly known as “Hamilton’s Folly,” this pioneer highway was rededicated in 1922 as Des Moines Memorial Drive and 1,432 American elm trees were planted along its shoulders to commemorate Washington state’s World War I dead. Some of these trees still line the memorial highway, part of which now forms SeaTac’s western border.

In the 1890s, on Sunnydale land that is now part of the north end of Sea-Tac Airport, Albert Paul and Gardner Clark homesteaded 160 acres and raised hops. At the turn-of-the-century the George Wilcox family settled on land that is now part of the North Satellite of the Sea-Tac Airport. Wilcox built the first blacksmith shop in the area. Some SeaTac residents of this second wave are buried near the south end of the Sea-Tac runway in the small Hillgrove Cemetery. Frederick Kingling donated the land for this first community cemetery in 1900, and the first burial was made in February.

In 1893, Angle Lake got its own school with three rooms and three teachers. The earliest schools were almost always one-room institutions with a single teacher handling all eight grades. As late as 1915, second wave SeaTac resident Bill Utterbach attended a one-teacher, one-room school named for the Manhattan neighborhood at what is now (2004) the southwest corner of the airport. Before the opening of Highline High School in 1924, many of the students on the ridge concluded their education with eight grades.

The Highline Life

Two pioneer communities on the Duwamish River began to develop in the early twentieth century on the “Riverton Heights” above the Duwamish River settlements of Riverton and Foster. McMicken Heights formed to either side of Military Road S and directly north of the Angle Lake neighborhood. Today, McMicken Heights and Angle Lake constitute the largest residential section of the City of SeaTac and are home to many of the community’s 25,000 citizens.

Many details of Highline life in the early twentieth century were fondly remembered by SeaTac residents who participated in the oral history project conducted by the Valley View Library in the mid-1990s. Jim Matelich remembered gathering eggs from the 500 chickens on the family farm and the summer chore of collecting and chopping wood for the winter -- 15 cords of it. Bill Bender recalled how the Bender family’s welfare depended on selling cords at $6 each. The percussion of stumps being loosened by dynamite was a commonplace noise as land was cleared for homes and farms. Many families had both chickens and cows. For refrigeration they built root cellars. For fun they had taffy pulls or, as Bill Utterbach remembers, played pickup baseball using dry cowpies for bases. Or they went swimming – most often in Angle Lake.

Taking the Plunge

During the 1920s, the Reeploeg family developed the west end of Angle Lake, the largest lake in SeaTac, into a popular resort. The elaborate diving platform constructed by the Reeploegs gave a splash to the name of their resort, The Angle Lake Plunge. Included were a slide, springboards, and a 20-foot tower. The price of admission was 10 cents, but boys like Bill Utterbach avoided the price by paying 5 cents at the Dreamland Resort on the opposite shore and swimming across to the Plunge.

The resort also featured rental boats and cabins, and a dance hall that attracted persons from far beyond the borders of the future SeaTac. The Blind Radio Five -- an orchestra of blind players accompanied by a sighted pianist -- was a popular attraction. In 1928, the Pacific Coast Highway (now Highway 99) replaced the West Valley Road as the main arterial between Seattle and Tacoma and boosted the numbers of visitors who took the Plunge. After the dance hall burned down in 1957, King County purchased the resort and reopened it as Angle Lake Park.

The new Pacific Coast Highway created new businesses all along its way, mostly for gas, food, and lodging. Two surviving examples are the Malmberg family’s grocery store with a vintage gas pump at the corner of Highway 99 and S 188th Street (opened in 1931), and the Hassen family’s gas station and Seven Gables Restaurant, which opened in 1935 and has served patrons as the popular VIP Tavern since 1947.

Dawn of the Air Age

Late in 1940, Dean Spencer and George Wolff cleared and graded a crude 1,700-foot-long airstrip in 70 acres of forest near Bow Lake. They completed a hangar by December 1941, but the Japanese attack at Pearl Harbor that month changed the plans of both young aviators. Private flying was prohibited within 150 miles of the Pacific Coast and Spencer and Wolff were soon off flying for the military.

Military flights and accelerated production of Boeing bombers quickly clogged Seattle’s Boeing Field and Sand Point Naval Air Station, Renton’s Bryn Mar Field, and Tacoma’s McChord Airfield. The federal government begged state and local governments to take up the challenge of building a new regional airport to meet war needs and serve future air travelers. Only the Port of Seattle heeded the call.

After rejecting a possible site on the Sammamish Plateau as too close to the Cascades, the Port selected Bow Lake airfield for the new airport, swayed in part by Tacoma’s promise of $100,000 to help pay for a facility that could serve it as well (the new airport ended up costing more than $4 million, so Tacoma got quite a bargain). Planners ignored warnings from longtime residents that the area was prone to thick and persistent fogs and quickly purchased more than 900 acres on the plateau.

Construction on the future Seattle-Tacoma International Airport began in January 1943, but the site proved more challenging than expected. Excavators had to dig as deep as 20 feet into the gritty glacial soil, and hauled away a total of 6.5 million cubic yards of dirt to create a level plateau. Then workers poured 450,000 square feet of concrete to create the main 6,100-foot runway and an “X” of adjoining taxiways. The original airport was officially dedicated on October 31, 1944, and promptly taken over by the Army Air Force to shuttle Boeing B-29s to and from the Pacific Theater. By then, Sea-Tac’s construction had cost $4,235,000, with most of the tab picked up by the federal government.

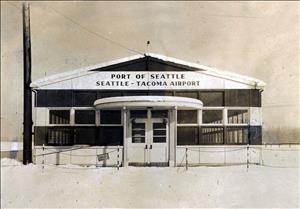

Limited civilian operations began in 1945, with waiting passengers and visitors confined to a Quonset hut heated by a single potbellied stove. King County voters approved a $3 million bond issue in 1946 to build a modern terminal and administration building. At its opening on July 9, 1949, Governor Arthur Langley warned the eagles and larks to move over, “for we, too, have won our place in the firmament of heaven.”

Growing Pains

As work progressed on Sea-Tac Airport during World War II, both Riverton Heights and McMicken Heights became bedroom communities for employees working in Boeing’s Seattle and Renton plants as well as on the new airport. Their populations tripled during the war, and King County approved fire districts for both neighborhoods. The construction of the Sea-Tac Airport was a considerable wartime attraction to those who lived near it. They soon dubbed the original control tower the “Easter Basket.”

The development of the Interstate 5 freeway in the 1960s created an unplanned eastern border for Highline and drew regional through traffic away from the old Pacific Coast Highway. The latter evolved into a seedy “strip” lined with bars, roadhouses, and cheap motels frequented by prostitutes, gamblers, and drug dealers. The neon-lined highway made national headlines in the 1980s as the hunting ground of the Green River Killer, who prowled it in search of some 48 female victims.

The rapid growth of air travel at Sea-Tac also changed the community’s character for both better and worse. The Port extended the main runway in 1956 to handle the new generation of jetliners, and undertook substantial terminal improvements for the 1962 Seattle World’s Fair. A second runway was completed in 1970, and the terminal continued to grow through successive additions over the next 20 years. By 1988, more than 20 million passengers passed through Sea-Tac annually, served by more than 14,000 persons working at jobs ranging from janitor to jet pilot. The Port of Seattle estimated that the number of persons who arrived at the airport each day equaled the population of Bellevue -- more than 80,000.

Noisy Neighbors

While the airport’s growth directly and indirectly supported thousands of new jobs and spurred the construction of adjacent conference hotels and business parks, it also attracted crime, and the arrival and departure of hundreds of jets every day generated more and more complaints about noise from nearby residents, businesses, and schools.

Even before jet aircraft began to fly regularly in and out of Sea-Tac in 1958, noise had disturbed the airport’s neighbors. The first “sonic” lawsuit was filed in 1950 by a poultry farmer who claimed his hens were not laying their expected quota of eggs. As takeoffs and landings by ever more powerful jetliners increased, so did the complaints of nearby businesses, schools, and residents. In response, the Port of Seattle began paying to soundproof the homes of some neighbors in the early 1970s and it purchased 420 acres north of its runways to create a public park in an “extended clear zone.”

Beginning in 1973, the Port joined with neighboring cities and communities to begin ratcheting down aircraft noise, to insulate homes and schools, and to acquire the hardest hit areas adjacent to the airport for parks and conservation areas. The formal “Sea-Tac Communities Plan” of 1976 led to the payment of millions to reduce or mitigate noise impacts and won national honors, but it did not silence all of the airport’s critics.

Third Runway

In 1988, planners at the Federal Aviation Administration, Puget Sound Council of Governments (now Puget Sound Regional Council), and Port of Seattle independently concluded that at current rates of air travel growth Sea-Tac’s two existing runways could reach its “maximum efficient capacity” as early as 2000. The Council of Governments then organized the Puget Sound Air Transportation Committee to guide a public involvement program of unprecedented scale, called “Flight Plan” to determine how the region could best meet its projected air service needs.

This study recognized that the narrow separation of Sea-Tac’s two existing runways (a mere 800 feet) posed a fundamental problem because it prevented the simultaneous use of the runways when weather limited pilot visibility -- which happens about 40 percent of the year. Thus, construction of a third “dependent” runway some 2,500 feet west of Sea-Tac’s second landing strip offered one approach to greatly expanding the airport’s effective capacity by allowing the use of two runways in bad weather.

The Flight Plan process, and an independent analysis by the State Air Transportation Commission (AIRTRAC), examined this and numerous alternatives and combinations including commercial use of Paine and McChord fields, construction of supplemental regional airports, more and faster commuter trains between Vancouver, B.C., and Portland, and even a cross-Cascades “bullet train” between Sea-Tac and a large airfield near Moses Lake in Eastern Washington.

Milking the Cash Cow

The third runway was not yet a major political factor in 1989 and early 1990. Rather, Sea-Tac’s immediate neighbors were frustrated with King County’s ability to deliver services, with rampant crime on the Highway 99 “strip,” and with their own inability to directly guide the community’s development.

There had been earlier efforts at incorporation. Some favored a larger city including more distant communities along the Highline ridge. The name proposed was, of course, Highline, but a smaller jurisdiction ringing the airport ultimately made more political and economic sense. As Joe Brennan, SeaTac Mayor in the mid-1990s, explained:

“We were a cash cow for King County. With the airport and the tremendous hospitality industry we have here there were revenues being produced that were never coming home. By surrounding the airport this community gets all the lease hold tax and we get a parking tax here where 50 cents is paid to the city in taxes for every car that parks at that airport. That’s a lot of 50 cents. Sea-Tac (the airport) is the engine that drives SeaTac (the city).”

The mail-in vote for incorporation on March 14, 1989, passed by 52.4 percent. It created a council-manager form of government with a largely ceremonial mayor chosen from the city council. The new city’s first mayor, retired pilot Frank Hansen, was fond of explaining that there were two factions on the first council and that he was chosen because he was an outsider to both.

The new city scored an early success through tougher policing, public works, and some clever public relations by patrolling and landscaping Highway 99 and changing its name to International Boulevard within the city limits. The amount of prostitution and related crimes fell dramatically.

A Quiet Approach

By 1995, Highline Times editor Rob Smith noted, “Burien, Des Moines and Federal Way were all a little envious of SeaTac’s wealth.” As Mayor Brennan then put it, “SeaTac can be described as very much a blue collar community with a champagne budget.” SeaTac refused to join its neighbors in opposing the third runway, which was approved in 1996 as the only viable alternative to meet the region’s projected aviation needs (it is slated for completion in 2008).

Instead, SeaTac negotiated its own bilateral “mitigation” agreement with the Port in 1997. The Port then developed abandoned residential blocks north of the airport into North SeaTac Park -- the largest park in SeaTac -- and the city built a popular Community Center there. At the south end of its runway, the Port of Seattle purchased the privately developed Tyee Valley Golf Course. Here the airport’s plans for its third runway will cut the 18-hole course to nine holes. The Port has proposed to replace -- perhaps by 2008 -- the lost nine holes on 65 acres owned by the City of SeaTac south of the exiting links.

In 2003, the teenaged City of SeaTac could count many civic, social, and economic assets. It moved its city hall into a former business building at 4800 S 188th Street and displayed artworks there from its growing permanent collection. The city planned to join with the Highline Historical Society to maintain museum exhibits in the District Court lobby.

Every year SeaTac is home to several parades, festivals, and fairs including the three-day annual International Festival at Angle Lake Park in June. The festival reflects the fact that the percentage of foreign-born residents living in SeaTac is near the top for King County communities.

Today (2004), citizens SeaTac and of contiguous communities like Tukwila are paying as much attention to how Sound Transit’s new light rail system will bind them to Seattle as to jets and runways. When rapid transit reaches SeaTac, it will be the latest version of a vision first imagined by the young Mike Kelly when he and his uncles built the Kelly Road between the river and the ridge in 1872.