Jacob Ziontz was a tenth-grade student in teacher Mikael Christensen's class at Shorewood High School when he won the 2010 HistoryLink.org award, senior division, for this essay on the history of Pacific Northwest Indian fishing and whaling treaty rights and the historic Boldt decision of 1974. Jacob's essay also won at both the local and regional levels of the National History Day competition, which HistoryLink is proud to support each year.

Broken Promises

Today, we see Native Americans in a respectful light. Gone are the old stereotypes of powwows, teepees, and headdresses. Especially in areas like the Pacific Northwest, Native Americans are viewed as a proud people, deserving of our respect and tolerance. This is in no small part due to the reacceptance of Native American treaty rights. These rights were established two hundred years ago by the founding fathers of our country, but were slowly forgotten and neglected. Thirty years ago, legal action taken by Native Americans helped them to regain their treaty rights, and the respect of the general public. The restoration of traditional Native American fishing and whaling rights in the Pacific Northwest in the mid to late 20th century promoted indigenous rights to natural resources not only locally but also nationally and internationally.

The dispute over Native Americans' rights to natural resources in the Pacific Northwest began in the 18th and 19th centuries, as the United States government was attempting to expand westward. The government gave its territorial governors one major goal: to procure as much land as possible as quickly as possible for the United States of America. However, they did not want to forcibly remove Native Americans from their lands. Instead, treaties were created that, in essence, traded the land the Native Americans lived on for various rights, privileges, and compensation. In less than one year, Washington territorial governor Isaac Stevens was able to procure 64 million acres of what is now Washington State, leaving only 6 million acres owned by the Native Americans (Chrisman). In 1855, Governor Stevens drew up one such treaty with the local tribes. The language barrier caused inexact translations and Governor Stevens was a crafty diplomat, so the tribes gave away many rights that they might have otherwise never ceded. However, the tribes stood their ground on one important issue: “the right of taking fish and of whaling or sealing at usual and accustomed grounds and stations”. This phrase from the “Treaty Between the United States of America and the Makah Tribe of Indians” guaranteed Native American tribes that they could continue to fish, whale, seal, and generally maintain access to their natural resources even though the land would no longer be theirs. In the fight for treaty rights more than a century later, this statement would be the foundation for Native American claims to rights to natural resources.

For a time, the rights secured by the Native American tribes in their treaty were upheld by all parties. But slowly, the authority of the treaties began to diminish, and the special privileges that Native Americans had because of the treaties were no longer recognized by state law. The treaty rights provided Native Americans the right to fish without restriction at their “usual and accustomed grounds." To the Native Americans of the Pacific Northwest, it seemed as though they had given their land in exchange for false promises, and there was little hope of such a small minority having an impact upon the powerful state governments that were opposing these rights.

Midway through the 20th century, the civil rights movement began in America. But while this phrase is more commonly associated with African-American empowerment, it had major impacts on the rights of Native Americans as well. The victories and achievements of the black Civil Rights Movement were an inspiration for minorities such as Native Americans to pursue their own goals of empowerment. Former Makah attorney Alvin Ziontz says that “[The legal cases brought forth by Native Americans in the 1960s and 1970s] was the equivalent of the black Civil Rights Movement.” Native American empowerment took place in the form of legal cases brought by the tribes and by individuals. At first, success was limited, and unfavorable rulings for Native Americans were common. Native Americans fighting for their rights were often ruled against in court, and no significant changes occurred. Then, the fight for Native American rights began to make headway in cases such as Satiacum v. Washington in 1973, which was given media attention and legal scrutiny. However, the culmination of decades of legal battle over Native American rights was U.S. v. Washington, a case more commonly identified by its historic conclusion: The Boldt Decision.

The Boldt Decision

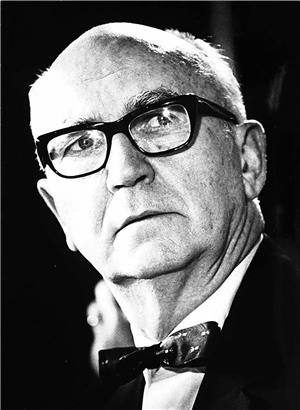

In 1970, the United States government, on behalf of the affected tribes, filed a case against the State of Washington in an effort to secure treaty rights for the Native American tribes that lived there. The reasons for this were many, but one of the federal government’s main incentives might have been the Cold War. During this time, the Soviet Union was criticizing the United States government for denying rights to their own indigenous peoples (Ziontz, Alvin. Personal Interview.). The main issue that was being debated was the Native American tribes’ right to fish in Washington State as their treaty provided. In 1974, after several years of legal proceedings and extensive deliberation, Federal Judge George Boldt issued his ruling on the case. In what would later be referred to as the “Boldt Decision”, Judge Boldt granted a major victory for Native American rights. He ruled, among other things, that Native American tribes in Western Washington were entitled to 50 percent of the annual catch of the salmon and steelhead species at the tribes’ “Usual and accustomed grounds (United States v. Washington). The U.S. Supreme Court later affirmed Boldt’s decision in 1979, which for the most part ended the legal dispute over this specific matter. In addition, Judge Boldt ruled that Native Americans could not be limited by the state as to where they could fish unless restricted by severe conservation measures. A consequence of this decision was that non-Native American commercial and sport fishermen were substantially limited in their ability to fish. This innovative decision "sent shockwaves throughout the state ..." (Ziontz, Alvin. Personal Interview).

The Boldt decision had a significant impact on indigenous peoples in many different respects. A flourishing Native American fishing industry developed, and many previously impoverished and despondent tribal members exercised their secured right as a new career. As a result, problems like Native American alcoholism, violence, and family disintegration were not solved, but were certainly alleviated by the Boldt decision. In addition, the general public’s view of Native Americans changed. Understandably, many non-Native American sport and commercial fishermen were upset about the new restrictions on their lifestyle, but the overall change in public view of Native Americans was positive. Native American history and culture began to be incorporated into public school curriculum, and the Native American tribal governments began to receive recognition in the same respect as state and federal government (Ziontz, Alvin: A Lawyer).

Makah Whaling

In the 1990’s, the Makah Indian Nation also regained another significant right. The Makah tribe had been hunting whale for thousands of years, but the white commercial whalers had decimated the whale population in the nineteenth century. In 1946, the International Whaling Commission (IWC) created an agreement, signed by many different countries including the United States, that essentially made whaling illegal, consequently stopping the Makah from their ancient practice (“International Convention For The Regulation Of Whaling”). This held true until 1999, when the population of the gray whale that the Makah hunted was reported to be at an all time high. The Makah announced that conservation was no longer an issue and that they would once again begin to whale.

The announcement that the Makah intended to hunt whale once again met immense opposition from many different organizations, from government agencies to animal-rights activists. But the Makah were determined to exercise their treaty right in order to preserve their culture and strengthen their tribal ties. What truly prevented them from whaling, however, was the IWC’s agreement, which made whaling illegal for the Makah. Fortunately, a solution was found. The Chukchi indigenous people of Eastern Russia had a generous whaling quota allowed by the IWC that they were for the most part not using. The Makah were able to reclaim their right by borrowing whales from this quota for their own tribe’s use. Of the 165 whales that the Chukchi were allowed to hunt every 5 years, they transferred the right to the Makah to take 20 whales every 5 years, or 4 whales every year (Ziontz, Alvin: A Lawyer). This agreement not only benefited the Makah and allowed them to regain their ancient tradition, but also was an inspiring collaboration of two indigenous peoples. On May 17th, 1999, for the first time in 70 years, the Makah people hunted and killed a whale. They were the only Native American tribe in the United States legally able to do so. This was a significant victory for Native American treaty rights and one that signified how far Native American treaty rights in the Pacific Northwest had come since the Boldt decision.

Wider Impacts of the Boldt Decision

The Boldt decision and cases like it had many impacts locally. But because of its innovative implications, it attracted attention from other indigenous people on a broader scale. In the United States, tribes from many different states used the Boldt decision as an authority for exercising their own treaty rights. The Chippewa tribe of the state of Minnesota had wording in their treaty with the United States government that was similar to that of the Makah treaty. “It shall not be obligatory upon the Indians, parties to this treaty, to remove from their present reservations (Treaty With The Chippewa).” They argued that because of what that wording meant for the Native American tribes of Western Washington, they should have the same rights as those tribes. They used this reasoning to help win legal cases and restore their treaty rights to natural resources. In addition, Native American tribes in Michigan, Wisconsin, and other states used the Boldt decision to win legal cases or to help establish a co-management of fisheries with the state governments.

But the Boldt decision’s impact goes beyond the boundaries of the United States. In New Zealand, the aboriginal Maori people made a treaty with its government similar to the treaty Native American tribes of Western Washington made with the United States government. The phrase “…the right of taking, at all usual and accustomed grounds and stations, is further secured to said Indians, in common with all citizens of the territory ..." (Treaty Between The United States of America and the Makah Tribe of Nations) in the Makah Treaty was argued by the Maori to be analogous to the phrase in the Treaty of Waitangi, which gives the Maori “full exclusive and undisturbed possession ..." (Treaty of Waitangi). The Maori pointed out this similarity to the governing British Crown in instances such as the Muriwhenua Fishing Claim and were able to retain full authority over their fisheries (Muriwhenua Fishing Claim).

In Australia, aboriginal tribes secured land rights in much the same way as Native Americans secured their fishing rights in Washington State. In the words of Australian Native Title lawyer Dr. Lisa Lombardi: “The treaty rights were upheld in a series of cases culminating in U.S. v Washington, more commonly called the Boldt decision. This decision has created an interest in public land in the U.S. very similar to native title interests in Crown lands in Australia … . [they] are viable and valuable interests that remain wherever they have not been explicitly extinguished and compensated for.”

And in Canada, First Nations saw the impacts of the innovative Boldt decision and thought they could secure their rights to natural resources in the same manner. In cases such as Sparrow v. The Queen, brought by First Nation tribe member Ronald Edward Sparrow against the Canadian Government, and Regina v. Sparrow, there were significant impacts by the Boldt decision. Associate Dean of Graduate Studies and Research at the University of British Columbia Douglas Harris commented on Regina v. Sparrow saying, “Thus, after conservation the Indian food fishery had priority. But conservation was, in the court’s words, a ‘compelling and substantial’ objective that would justify the federal government’s infringement of an Aboriginal right to fish. To this extent, the judgment mirrored the Boldt decision without citing it.”

It is clear that the Boldt decision was an innovative use of the law, and it had a huge impact on matters of aboriginal rights to natural resources around the world. Unlike many great moments of change throughout history, the innovation of the Boldt decision came not in the form of a new technology or law, but in a unique application of the law. Boldt took the original treaty between the Native Americans and the United States government and interpreted this treaty as the Native Americans would have understood it at the time it was signed. It was this interpretation of a law that already existed that was the innovation of Boldt’s actions. When Judge Boldt implemented the treaty law in such an innovative manner in his historic decision, it was a momentous change that would have an effect on aboriginal peoples worldwide. In the words of Seattle PI columnist Lewis Kamb: “Dozens and dozens of cases, and I’m sure well into the hundreds, have cited Boldt’s precedent-setting ruling.”

The Boldt decision and legal cases like it in the mid to late 20th century had significant impacts on the local communities where they were decided. But they also had impacts on a broader scale. The Boldt decision impacted Native Americans in Western Washington by securing their treaty rights to natural resources. In addition, in the Midwest United States, aborigines in New Zealand and Australia, and First Nation tribes in Canada, impacts of the Boldt decision were present in the form of a legal precedent for future cases. Though it was initially a victory for only a small percentage of native people, it became one of the century’s most significant victories for aboriginal peoples worldwide.

Sources:

Annotated Bibliography

Dark, Alx. “The Makah Indian Tribe and Whaling: A Fact Sheet Issued by the Makah Whaling Commission” Native Americans and the Environment, 25 May 1994. 2 Oct. 2009. http://ncseonline.org/NAE/docs/makahfaq.html. “Online Fact Sheet.”

This source was a website launched on behalf of the Makah Native American tribe by a non-Native American in 1994. Its primary purpose was to publish the opinions and perspective of the Makah nation prior to the 1999 Makah whale hunt, when the topic still had much controversy around it. Though the website was mostly written by the author Alx Dark, it was officially created in cooperation with the National Council for Science and the Arts. The main document from this source that was researched in this project was a fact sheet created to portray the views and provide information about the Makah Native Americans and their intent to continue hunting whales in their “usual and accustomed grounds” as promised in their treaty with the United States. This can be best described as a primary source because it was written by a Public Relations representative for the Makah tribe at the time that the whaling controversy was taking place. The source has an obvious slant in favor of the Makah Native Americans because the author was working a Public Relations representative, but most if not all of the information has been checked for accuracy and is correct.

“International Convention For the Regulation of Whaling.” International Whaling Commission. 11 Mar. 2008. 9 Oct. 2009. http://www.iwcoffice.org/commission/convention.htm#convention. “International Convention.”

This document is responsible for limiting and ultimately preventing the Makah Native American tribe from hunting whales in Neah Bay. It was created in 1946 and signed by various nations around the world including the United States, which is why it is pertinent to the Makah nation. The document states, in short, that any country that signs will be subject to the decisions of the International Whaling Commission (IWC) in regards to whaling restrictions and regulations. The IWC was to be composed of one member from each signing country and his supporting experts and scientists. This Commission eventually decided to ban whaling with the exception of a few indigenous tribes that used whaling as a source of food, and the Makah did not fall under this category. This is a primary source because it is the text of the direct cause of the Makah nation’s loss of whaling rights.

R. V. Sparrow. 1 S.C.R. 1075. (1990). Judgments of the Supreme Court of Canada. University of Montreal. 3 Nov. 2009. “Supreme Court Case.”

This source is a judgment by the Supreme Court of Canada regarding First Nation tribe member Ronald Edward Sparrow who is fined by the federal government for fishing with an oversize net. His claim is that he has the right to fish however he chooses since he is protected by his treaty rights. The First Nation tribe member cites the Boldt decision in this case, showing the Boldt decision’s widespread application throughout the world. This is a primary source because it is the actual court proceeding of the trial described above. The official title of this case is Ronald Edward Sparrow v. Her Majesty The Queen, or Sparrow v. The Queen. This is because the Queen represents the Canadian federal government, which is involved in the case. The case was found on an online database called “Judgments of the Supreme Court of Canada.”

Treaty Between The United States of America and the Makah Tribe of Nations. 18 Apr. 1859. University of Washington Libraries Digital Collections. University of Washington. 1 Oct. 2009. http://content.lib.washington.edu/cdm4/document.php?CISOROOT=/lctext&CISOPTR=1576&REC=18&CISOSHOW=7606. “Federal Treaty.”

This document is the original treaty between the United States and the Makah tribe. It has been made into digital text and put on the Internet for public use by the University of Washington Libraries. The treaty essentially describes what the United States government, under the direction of former Washington Territory Governor Isaac Stevens, promised to provide for the Native Americans of the Puget Sound Region in exchange for their land. This source is a very reliable primary source as it is an exact copy of the original words written down in 1855 that were agreed to and signed upon by the United States’ representatives and the various chiefs of the Native American tribes of the Puget Sound region. It was extremely helpful in determining what the was language of the treaty that was so influential in the 1960s and 1970s legal cases of the Native American Civil rights movement. This source was surprisingly easy to read and understand for a complex legal document of the 19th century. It clearly outlined all of the actions its enactment would carry out if it were signed.

Treaty of Waitangi. 6 Feb. 1840. New Zealand History Online. History Group of the New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage. 13 Dec. 2009. http://www.nzhistory.net.nz/politics/treaty/read-the-treaty/english-text. “Federal Treaty.”

The Treaty of Waitangi is the document the government of New Zealand, which in 1840 was the British crown, signed with the indigenous Maori of New Zealand. It is comparable to Native American treaties in that the indigenous Maori are ceding the possession of their land in exchange for monetary and social gain. The analysis of this document was essential in comparing the Native American and Maori treaties in this project. It is a primary source because it is the text of the original treaty created when the Maori negotiated their land rights with the New Zealand government. A picture of the original document with a zoom function was also available on the website I located the treaty on, so I was able to see the original treaty and even read parts of it, although the distorted writing was sometimes illegible.

Treaty With The Chippewa Of The Mississippi And The Pillager And Lake Winnibigoshish Bands. 11 Mar. 1863. Indian Affairs: Laws and Treaties. OSU Library Electronic Publishing Center. 3 December 2009. http://digital.library.okstate.edu/kappler/Vol2/treaties/chi0839.htm. “Federal Treaty.”

This is the treaty the Chippewa tribe of Native Americans signed with the United States government. Just like in the Pacific Northwest, the Chippewa cede their land to the U.S. government in this treaty in exchange for various forms of compensation. This is a primary source because it is the original text of the treaty the Chippewa signed with the U.S. government. It is important to this project because it is comparable to the treaties with the Native Americans of the Pacific Northwest and it can be analyzed how the two impacted each other. This online copy of the treaty was found through a law and treaty database that was very helpful in my research.

United States v. Washington. 384 F. Supp. 312. (1974). Center For Columbia River History. 7 Oct. 2009. http://www.ccrh.org/comm/river/legal/boldt.htm. “District Court Case.”

This is the full text of the historic Boldt Decision, the conclusion of the U.S. v. Washington case that resulting in restoring the Pacific Northwest Native American tribes’ fishing rights. The document consists of the full and exact words of Judge George Boldt as well as a summary of the attorney’s arguments, recorded at the time of the case. This is a primary source because it is either the exact words of the members of the case or a summary of their words as the case was happening. It is somewhat hard to read through because of its confusing legal format and language, but it contains essential information to obtaining information about the restoring fishing rights of the Pacific Northwest Native Americans.

Ziontz, Alvin. A Lawyer in Indian Country. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2009. “Book.”

Alvin Ziontz’s close association with Native Americans and his work on the Boldt case and Makah whaling rights makes him a very qualified source. His book, A Lawyer in Indian Country, gives a detailed account of his life as an Indian law attorney. The book is written as a memoir, but because of the nature of his career, Ziontz includes many details regarding legal cases and facts. This is a primary source because it is a direct account by a lawyer who personally worked on and around these cases. The book was published in 2009 and so is a very recent and up to date source for information about the eventual outcomes of the Native American civil rights movement’s legal cases. The book also gives information about Ziontz’s personal life, as is customary with memoirs, and is less relevant for the research purposes that it was used for in this case. Overall, this book is a detailed and accurate account of the legal cases of the Native American civil rights movement with some irrelevant information that is interesting but unnecessary in a research situation.

Ziontz, Alvin. Personal Interview. 24 Oct. 2009 “Personal Interview.”

Alvin Ziontz was an attorney litigating for the Makah Indian nation and other Native American tribes in the U.S. v. Washington case. He has access to specific knowledge about how the Boldt decision came about that few are able to provide. He also was the longstanding attorney for the Makah Indian Nation and served as a public relations representative to them during their attempts to reclaim their whaling rights. This interview was conducted in order to obtain information from a source that was “behind the scenes” and also deeply invested in the topic. This is primary source because it is information and opinion that comes from a person directly involved in the U.S. v. Washington case at the time of the case. The interview asked questions about the impacts of the Boldt decision and the restored Makah whaling rights as well as the historical context of these two

SECONDARY SOURCES

“American Indian Movement.” Minnesota Historical Society Library. Minnesota Historical Society, Minneapolis, Minnesota. 22 October 2009. http://www.mnhs.org/library/tips/history_topics/93aim.html. “Online Database Entry.”

A brief encyclopedic description of the American Indian Movement (AIM). This was a movement of the 1970s and 1980s but also an official organization composed of Native American members that became official in 1968 and today work with the United States Bureau of Indian Affairs. This source talks about the AIM in the context of its history, achievements, and modern role in society. The authors are the staff of the AIM and Native Americans themselves, so the source is reliable. However, the source is simply a retelling of the AIM’s history, so it is a secondary source. The source was used in this project to help put the Boldt decision and the restored Makah whaling rights in context with other Native American historical events of the era.

Chrisman, Gabriel. “The Fish-in Protests at Frank’s Landing.” UW Departments Web Server. 12 Aug. 2006. UW Departments, Seattle, WA. 29 Sept. 2009. http://depts.washington.edu/civilr/fish-ins.htm. “ Historical Essay.”

This is an in-depth essay about the Native American rights protest that occurred at Frank’s Landing. It not only covers the protests at this location, however, but also the many events that led up to and followed this event, such as the Native American fishing treaties that came before and the Boldt decision of 1974 that came after. The author, Gabriel Chrisman, doesn’t have any specific credentials mentioned, but his article is featured in an online collection of essays sponsored by the University of Washington, so it is assumed that he is fairly credible. It is a very detailed source but it is secondary and the author might have had a bias when he wrote it. Along with an extensive analysis of the Frank’s Landing protests and the events surrounding them, there are also a good number of primary-source images from the era with captions throughout the article.

Crowley, Walt and Wilma, David. “Federal Judge George Boldt issues historic ruling affirming Native American treaty fishing rights on February 12, 1974.” HistoryLink.org. 29 Sept. 2009. http://www.historylink.org/index.cfm?DisplayPage=output.cfm&File_Id=5282. “Online Encyclopedia Entry.”

This source is a good brief review of the Boldt case and the major events relating to it. It discusses the Boldt decision, why it was made, and how history shaped its eventual outcome. This article is purely a secondary source and so a bias by the authors should be considered. The authors, Walt Crowley and David Wilma, have no credentials mentioned on the site but are both respected Seattle journalists and historians. The site itself is an online encyclopedia sponsored by well-known institutions like the State of Washington, Paul Allen, and the Museum of History and Industry. The essay is short enough and the information it contains is concise enough so that the essay itself can easily be checked with other sources to determine its credibility and bias. This essay was a great introduction to the complicated and intricate topic of the 1974 Boldt Decision.

Harris, Douglas C., The Boldt Decision in Canada: Aboriginal Treaty Rights to Fish on the Pacific (2008). THE POWER OF PROMISES: RETHINKING INDIAN TREATIES IN THE PACIFIC NORTHWEST, Alexandra Harmon, ed., University of Washington Press, 2008. Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1394436. “Historical Essay.”

This source is an essay written by Douglas Harris about the impact of the Boldt decision in Canada. Harris specifically focuses on the how the United States and Canada each interpreted their indigenous peoples’ treaty rights in regards to fishing. Essentially, the essay asks how the Boldt decision and decisions like it compare to their Canadian counterparts. This is secondary source because it is an author removed from the topic in question, giving his opinion on the subject. Douglas Harris is the associate Dean of Graduate Studies at the University of British Columbia, and so is a very credible source. The essay is quite long and detailed, but certain parts were filled with helpful information and strengthened this project.

Kamb, Lewis. “Boldt ruling’s effect felt around the world.” Seattle Post-Intelligencer 12 Feb. 2004. Morriset, Schlosser & Jozwiak Search. 23 Oct. 2009 http://www.msaj.com/Boldt021204.htm. “Online Newspaper Article.”

This was a very brief online newspaper article that was nonetheless essential to this project’s research. The article asserted that the Boldt decision had impacts not only in the Pacific Northwest but also all around the world. This was in essence this project’s thesis, and so the article provided a very key array of information. The author, Lewis Kamb, has written many articles relating to the Boldt decision and Indian Law, and so is reliable. Although this is a newspaper article, it is a secondary source because it is the author’s interpretation of the facts after the events that are the subject of the source. The article discusses the effects of the Boldt decision being felt in the Pacific Northwest, around the United States, and in other countries such as Canada and Australia.

Kamb, Lewis. “Boldt decision ‘very much alive’ 30 years later.” Seattle Post-Intelligencer 12 Feb. 2004. seattlepi.com. 24 Oct. 2009. http://www.seattlepi.com/local/160345_boldt12.html. “Online Newspaper Article.”

A newspaper article that describes the effects of the Boldt decision on its 30 year anniversary. The piece draws attention to the fact that the fishing rights dispute has been put to rest, but the fight over conservation is still at large. Author Lewis Kamb is a credible source with much experience in the background of the Boldt decision and Indian law. This secondary source reviews a case long since decided, even though there are still unresolved issues today. This article served to provide relevance for the Boldt decision in this topic. The article interviews several important figures in Boldt decision from both sides of the debate. This provides many useful and enlightening quotes to be used in this project.

Lombardi, Lisa. “American Indian Rights: Some Observations and their Implications for Australia.” Australasian Legal Information Institute. 9 Jan. 2004. UTS and UNSW Faculties of Law. 11 November 2009. http://www.austlii.edu.au/cgi-bin/sinodisp/au/journals/ILB/2004/9.html?query=Boldt%20decision. “Law Bulletin Entry.”

Dr. Lisa Lombardi, an expert of Native Title Law in Australia spent much time in the Pacific Northwest studying Native American Law. She therefore has an extensive knowledge of the relationship between Northwest Native American treaties and Australian and New Zealand aboriginal treaties. This was crucial in this project where the two types of treaties and their interdependence were examined. This was a secondary source because it was removed analysis of a topic by an expert who was not directly involved in the creation of these treaties. Lisa Lombardi is a reliable source because of her extensive knowledge of and background in Native Title Law.

“Muriwhenua Fisheries Claim.” Waitangi Tribunal. 10 Nov. 2009. http://www.waitangi-tribunal.govt.nz/reports/viewchapter.asp?reportID=337EEC7B-555A-47A5-910E-B12796A26C01&chapter=13. “Online Report.”

This document is an extended analysis of the Treaty of Waitangi and its role in New Zealand’s history. It compares the Treaty of Waitangi to other treaties and legal cases concerning treaty rights. It was critical in the research of this project because it helped to understand the role of the Boldt decision in New Zealand. It is a secondary source because it is a removed analysis, not a firsthand account. Although there is no recognized author, it is supported by the Waitangi Tribunal, an esteem tribal law organization of New Zealand. The document found on this website was very lengthy, and it should be noted that only parts relating to Native American treaty rights in Washington State were considered.

Oldham, Kit. “Makah Whaling. HistoryLink.org. 19 Oct. 2009. http://www.historylink.org/index.cfm?DisplayPage=output.cfm&File_Id=5301. “Online Encyclopedia Entry.”

This encyclopedia entry was a very good piece of background information for this project. The article especially focuses the historical context of the Makah whale hunt, an item often lost or forgotten in the controversy of the hunt itself. This is a secondary source as the author was not a first-hand witness but is merely stating facts founded by his research. The author himself, Kit Oldham, is the Staff Historian of the online encyclopedia History Link, an organization funded by, among other notable sponsors, the State of Washington. This is a great source for “filling in the cracks” of one’s research, because it doesn’t go into too much depth or insight of any subject, but covers practically all aspects of the historic Makah whale hunt.

“The Native American Movement” Country Studies. December 4, 1986. 7 Oct. 2009. http://countrystudies.us/united-states/history-133.htm. “Online Database Entry.”

This source was from a database-like website that collected the contents of books from 1986-1998. It was created by the Federal Research Division of the Library of Congress as part of the Country Studies/Area Handbook Series sponsored by the U.S. Department of the Army. There are detailed studies of many historical events from almost every country around the world. The specific page used for research in this project was an excerpt about the Native American Movement as part of United States History. This excerpt was very brief and concise but informative. It put the Native American movement of the 1960s and 1970s in context with other United States History occurring at that time. It also gave this project a broader perspective about the Native American civil rights movements going on outside the Pacific Northwest region, which this project focuses on almost entirely. This excerpt was a secondary source because it is by a historian recounting the events in United States History from others’ accounts, not from his own experience.

Licensing: This essay is licensed under a Creative Commons license that

encourages reproduction with attribution. Credit should be given to both

HistoryLink.org and to the author, and sources must be included with any

reproduction. Click the icon for more info. Please note that this

Creative Commons license applies to text only, and not to images. For

more information regarding individual photos or images, please contact

the source noted in the image credit.

Major Support for HistoryLink.org Provided

By:

The State of Washington | Patsy Bullitt Collins

| Paul G. Allen Family Foundation | Museum Of History & Industry

| 4Culture (King County Lodging Tax Revenue) | City of Seattle

| City of Bellevue | City of Tacoma | King County | The Peach

Foundation | Microsoft Corporation, Other Public and Private

Sponsors and Visitors Like You