Kylie Heintzelman was a 10th Grade student at Mt. Spokane High School when she won the HistoryLink.org award for her Senior Division Paper in the 2011 state competition for National History Day. Her advisor was Luke Thomas. We are proud to publish her essay on Gordon Hirabayashi (1918-2012) and his resistance to the military order for Japanese Americans to evacuate the West Coast in 1942, during World War II.

Hirabayashi v. United States: An Inspiration During War

“I was always able to hold my head up high, because I wasn’t just objecting and saying ‘no,’ but was saying ‘yes’ to a prior principle, the highest of principles,”[1] said Gordon Hirabayashi. Hirabayashi v. United States, an influential Supreme Court case regarding the treatment of Japanese Americans during World War II, held true to the moral principles on which he conducted his debate.

Hirabayashi’s case technically ended in failure, yet it succeeded in leading the way for others challenging Japanese Internment to make their unjust fate known. Gordon Hirabayashi did not win his Supreme Court case, yet the fact that he questioned the constitutionality of Executive Order 9066 and Exclusion Order No. 57 by purposefully refusing to follow the exclusion order and curfew, stayed with his case until it reached the Supreme Court, and pursued the reversal of his convictions later in life gave others with similar views of internment inspiration and hope in a time of distress.

Issued on February 19, 1942, Executive Order 9066, gave the military the power to ban any citizen from an area stretching along the coast of Washington to California and extending inland to Arizona. It ordered evacuation of a large number of immigrant-Americans, especially Japanese because of the bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941.[2] Another proclamation, issued on March 24 1942, by General John DeWitt was casually referred to as the curfew order. It restricted all German, Italian, and Japanese aliens, plus Japanese non-aliens, to their homes between 8:00 P.M. and 6:00 A.M.[3]

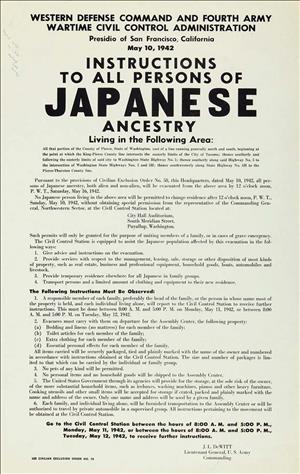

During this time, Gordon Hirabayashi, a student at the University of Washington, could already feel the effects of this racial discrimination:[4] Hirabayashi followed the curfew order daily, until he questioned his actions, “Why am I rushing back and my dorm mates are not? Am I not an American citizen the same as they?”[5] From then on, Hirabayashi intentionally disobeyed the curfew order. Soon after the curfew order, the government published another proclamation: On May 10, 1942, Exclusion Order No. 57 required people of Japanese ancestry, both alien and nonalien, to be excluded from parts of Military Area No. 1, and to register to assigned Civil Control Stations.[6] Once again, Hirabayashi disobeyed, refusing to register by May 16, when he was supposed to.

Viewing these orders as a violation of his Constitutional rights, Hirabayashi decided to challenge these proclamations. Soon, Hirabayashi caught the attention of others, including Senator Mary Farquharson, who aided Hirabayashi to take legal action. Farquharson, civil liberties activists, Quakers, peace organization members, ministers in Seattle's University District, professors, and businessmen formed the Gordon Hirabayashi Defense Committee. Businessman Ray Roberts was chair and treasurer, Farquharson was the general secretary, Arthur Barnett worked on endorsing his case, and Frank Walters was Hirabayashi’s attorney.[7] That Hirabayashi was able to get so many people to come together to support him so early in his case, before it even reached a courtroom, suggests the potential of one man to influence many during the turmoil caused by the curfew and exclusion orders.

While pursuing legal action, Hirabayashi stayed at the University YMCA, but, not wanting the University to get in trouble for protecting a fugitive, he turned himself in to the FBI, following the instruction of his legal advisor, Arthur Barnett. Hirabayashi was charged for breaking the curfew and exclusion order, and from then he spent five months in the King County jail to wait for his trial. On October 20, 1942 Hirabayashi’s trial was held, the first trial of its kind.[8] Frank Walters represented Hirabayashi, and he argued that the curfew and evacuation violated the Fifth Amendment and Japanese American rights as a racial minority.[9]

Ultimately, the jury ignored these claims about unconstitutionality, and focused only on Hirabayashi’s actions. Hirabayashi was found guilty because he admitted that he had not reported to the Civil Control Station and had disobeyed the curfew. The federal district court sentencing was originally 30 days on count 1 for ignoring the exclusion order and thirty days on count 2 for breaking the curfew. Hirabayashi asked to add 15 days to each sentence because a sentence of at least 90 days allowed him to serve time in an outdoor road-camp. Judge Lloyd Black suggested making the sentence 90 days for each: Hirabayashi agreed, and spent his sentence in a prison camp in the Santa Catalina Mountains in Arizona.[10]

Before the Supreme Court

After serving 90 days of his sentence, Hirabayashi went before the Supreme Court with his case.[11] Harold Evans and Frank Walters argued for Hirabayashi. Evans argued that Public Law 503 -- which stated that anyone who entered, remained in, left, or committed an act in a military area prearranged from the authority of an executive order violating the restrictions in that area, would be guilty of a misdemeanor [12] -- was an unconstitutional allocation of the lawmaking power to General DeWitt. Walters also argued that DeWitt’s orders were dishonest.

Charles Fahy then presented the government’s argument. Fahy argued that the powers that the Congress and President shared for acting during wartime took precedence over the rights of citizens. Fahy also argued that, to convict Hirabayashi, the Court only needed to find that Hirabayashi had knowledge of the orders and that he had deliberately disobeyed them.[13] In Hirabayashi’s opposition, Hirabayashi was presented as a person of Japanese ancestry who broke curfew and exclusion orders that were legitimate and honest laws. The prosecution held the focus of the trial was not about the Constitution, but about a citizen breaking the law. Eventually, because of Hirabayashi’s 90 day sentence, the Supreme Court chose to dwell on his violation of the curfew order, and Hirabayashi was declared guilty. On June 21, 1943 Hirabayashi was sent back to prison.

The fact that Hirabayashi stuck with his faith in the Constitution through two losing trials, even saying: “I at first questioned the effectiveness of the Constitution ... Fortunately I did not give up on the Constitution,”[14] illustrates Hirabayashi’s steadfast conviction in his country, which inspired others to aid him notwithstanding that years had passed after his original trials.

The New Japanese American Internment Cases

In the early 1980s, Aiko Herzig-Yoshinaga, a senior archival researcher for the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians, found an original draft that had been used in order to justify Japanese-American removal and relocation. The draft showed inconsistencies with the copy used in Hirabayashi’s federal court hearings in 1942 and 1943.[15]

Soon after that, Peter Irons, a historian and political science professor, found correspondence between the lawyer that made the Supreme Court brief in Hirabayashi’s case, Edward Ennis, and Charles Fahy. Fahy had withheld this correspondence, a report regarding racial bias, from Supreme Court. This evidence showing error in Hirabayashi’s trial, led Hirabayashi to request a new hearing for his case. The legal justification was based on the writ of coram nobis, an order by a court of appeals to think about details that are not on the trial record, which may have changed the outcome of the case if it had been known at the time of a trial.

So Hirabayashi, joined by Fred Korematsu and Minoru Yasui (who had endured similar trials during WWII and whose cases would have been affected by this evidence) had their hearings. Hirabayashi’s hearing was the last of the three, and when it came time for his hearing, attorneys fought for dismissal because of technicalities, saying that the allowed time for a petition had expired, and that since Hirabayashi had become a successful professor he had not suffered from his wartime convictions, so he did not qualify for a coram nobis petition.[16]

In 1986 Judge Donald Voorhees ruled that the time for a petition should be extended and that Hirabayashi had indeed suffered because he had been accused of a crime based on race, causing lasting grief. The decision on whether Hirabayashi’s wartime convictions should remain the same came in February 1986. Hirabayashi’s convictions were decidedly overturned on technical grounds, but his Supreme Court rulings from the case remained the same.[17]

Racism in America

Although not as well known as civil rights dissidents in the early 1950s and 1960s, Japanese Americans were still subject to the same kind of racial discrimination during WWII, more than German or Italian Americans during World War II, because of their obvious heritage.[18] People and groups organized against Japanese Americans, believing them to be America’s enemy. Newspapers such as The Japanese Exclusion League Journal propagated news about Japanese who were perverting American citizens with quotes such as, “Admiral Halsey says: ‘We have found definite signs of cannibalism among the Japs. In defeat they revert to wild beasts.’”[19] Other articles circulated “The Yellow Peril,” insisting that Japanese Americans were corrupting white society.[20]

This sort of discrimination was mainly propaganda, in that upon reading, little evidence proves the truth in these assertions. For example, in The Japanese Exclusion League Journal, it is claimed that “The Japanese in the United States, considering the exigencies of war, have been exceptionally well treated,” but as the article continues, no evidence is provided to support this claim.[21] In many ways, Gordon Hirabayashi’s case raised lingering questions about racial prejudice for Japanese-Americans during World War II. Historically, Hirabayashi v. United States was significant because it was the first case during World War II to raise questions about the morality of Japanese Internment.[22] Although, amidst the conflict of World War II. Hirabayashi’s case was not nationally well-known, it was locally known by Hirabayashi’s supporters, family, and friends, and it did indeed question the morality of racial exclusion shown by groups and orders against Japanese-Americans.[23]

Legacy of the Case

Reflecting on his actions during World War II, Gordon Hirabayashi said, “Raising constitutional and moral questions during World War II, as I had done, was not the norm.”[24] Gordon Hirabayashi’s trial, his Supreme Court trial, and his hearing in 1986 may not seem revolutionary looking back because cases with similar problems emerged during World War II, but at the time, most Japanese Americans did not question their internment or curfews the way Hirabayashi did.

Another significant aspect of Hirabayashi’s case was that it was the first to question internment. It was even said that, “His case before the Supreme Court, Hirabayashi v. United States, was the first challenge to the government’s wartime curfew and expulsion of Japanese-Americans.” [25] There were, of course, others who took the same measures that Hirabayashi did in taking legal action because of the harm they endured being Japanese Americans during World War II, but Hirabayashi’s cases proved very inspirational. While Hirabayashi’s mother was in a prison camp, two women confronted her about her son: “When they finally located her, the two women said they had heard that the mother of the fellow in jail fighting for their rights was housed in that block. They had come to greet her and say ‘Thank you!’”[26]

When the evidence of distorted facts in the cases of Fred Korematsu, Minoru Yasui, and Gordon Hirabayashi was discovered, Aiko Herzig-Yoshinaga originally presented the information to Hirabayashi.[27] Through his good will, Hirabayashi reached out to Korematsu and Yasui so they too could have the same opportunity to further pursue their cases. Not only did Hirabayashi inspire people when he was young, his story continues to inspire young people today.

An example of someone inspired by Hirabayashi is Ryun Yu, who played Hirabayashi in “Dawn’s Light: The Story of Gordon Hirabayashi,” a play about Hirabayashi. Contemplating Hirabayashi’s story, Yu said: “Gordon Hirabayashi taught me so much of what it is to be a man. I did a lot of research on the time, on the places where he grew up and lived. As the work went on, I became a little awed. I think like many extraordinary people, it might be easy for him to hide those world-conquering qualities that he possesses.”[28]

While Hirabayashi v. United States was did not succeed for Gordon Hirabayashi, Hirabayashi did manage to stick through two trials, prison camp, and the unconstitutionality of Japanese internment during World War II. The very fact that Hirabayashi stayed with his cases, convinced that justice would eventually prevail, proves inspiring enough. The act itself, of pursuing deserved justice over 40 years after his original cases demonstrates that Hirabayashi’s willful resistance to Executive Order 9066 and Exclusion Order No. 57, was indeed a successful and influential dispute, not only in his own life, but in that of others, then and today.