Jack Hanley, a Junior at Seattle Prep, won first place in the Senior Division of the 2007 History Day competition with this essay on Bainbridge Island's Japanese American incarceration.

A Community's Tragedy and Triumph

At the onset of World War II, over 122,000 Japanese Americans living in the Western United States were forced to leave their homes by order of the government. Almost all were sent to internment camps in remote locations away from the West Coast. For many of them local community pressure, fueled by war hysteria and racism, drove them out of their neighborhoods (Kashima 175). The experience of the Japanese-Americans on Bainbridge Island, Washington, was quite different. Japanese Americans were an integral part of the fabric of this island community; for that reason, their expulsion was more painful than elsewhere, but those community ties also greatly helped in their triumphant return at the end of the war.

The Japanese American community thrived on Bainbridge Island, living in harmony with other races until the Pearl Harbor attack (Visible Target). At the end of the nineteeth century, Bainbridge Island's Port Blakely mill, the largest in Washington, drew laborers from several countries including Japan. In 1890, the mill employed 200 Scandinavians, 50 Americans, and 24 Japanese (Swain 3). The Japanese mill workers eventually gravitated to agriculture. They had arrived with farming skills and an intense work ethic. No competition existed for this kind of difficult work, and the Japanese provided produce which the white population valued.

Wealthy Seattle families with summer homes on sparsely populated rural Bainbridge Island did not oppose settlement by the Issei, first generation Japanese Americans (Swain 3-7, 14). Despite their contributions and acceptance, the Issei faced barriers, including the 1921 Alien Land Law which forbade land ownership by noncitizens (Niiya). Japanese aliens found ways to sidestep the law by leasing property and eventually purchasing land in the names of their children (Nisei), who were American citizens. By 1940, there were 54 Japanese-ancestry families located on the Island, and they had become an integral, important part of the Bainbridge community (Swain 9, 19).

The shocking attack of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, threw the U.S. into a state of war against Japan. The next morning, publishers Walt and Millie Woodward released a special "War Extra" issue of their newspaper, the Bainbridge Review. In it they reassured their fellow islanders that the 300 Japanese Americans living on Bainbridge were completely loyal to the United States (Woodward, "War Extra"). They urged the community to look past the ancestry of their Japanese neighbors and to continue to accept them as loyal Americans.

"These Japanese-Americans of ours haven't bombed anybody. In the past, they have given every indication of loyalty to this nation ... Let us so live in this trying time that when it is all over loyal Americans can look loyal Americans in the eye with the knowledge that, together,

they kept the Stars and Stripes flying high over the land of

the brave and the home of the free" (Woodward: War Extra).

Woodward was the only editor of a newspaper in Western Washington to loudly and repeatedly stand up for the local Japanese and Japanese American residents (Hannula).

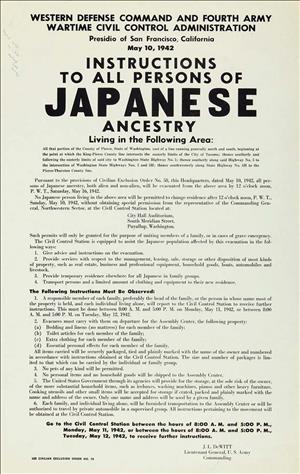

Fear of anything Japanese soon spread throughout the country. On February 19, 1942, President Roosevelt issued Executive Order No. 9066, which gave local military authorities the power to do whatever was necessary to protect the nation from the Japanese enemy (Roosevelt). As one historian wrote, "The belief that Japanese American citizens were untrustworthy and likely to engage in spying and sabotage was considered almost conventional wisdom" (Neiwert 123). Soon this led to the forced removal from their homes of all Japanese and Japanese Americans living along the West Coast. Bainbridge Island was the first to suffer (Niiya).

On March 24, 1942, military authorities issued Civilian Exclusion Order No. 1, requiring the removal of all Japanese and Japanese Americans from Bainbridge Island. Both Issei and Nisei were given only six days to prepare for the move (Ohtaki). This was a complete disruption of all aspects of life. The Island Japanese had to make arrangements regarding their property, complete their goodbyes, and evaluate what possessions they would take with them, as they were allowed to take only what they could physically carry (Visible Target). Their Island neighbors helped them as best they could by agreeing to care for their farms and protect their homes.

This was in sharp contrast to other communities, such as Bellevue, Washington; when a relocation order was issued for that area, the white neighbors chose to take advantage of the situation. There were many instances of whites buying household goods for unfair prices from the evicted Japanese and taking possession of farmland with no intention of sharing the resulting profits (Neiwert 134-138). Mitsi Shiraishi, a Japanese woman from Bellevue, recalled, "People came to buy things for nothing. And they would offer you a measly five dollars or something for something that we could still use" (Neiwert 138).

When news of Exclusion Order No. 1 hit Bainbridge, Woodward became furious and began a series of newspaper articles defending the Islanders and criticizing the forced removal. He also argued that such a violation of constitutional rights could be directed at anyone (Holt). Woodward said, "The Review has stuck its neck out good and proper for you people not because you are [you people] but because you are Americans and temporarily have lost the citizenship rights this nation guarantees to every citizen" (Ohtaki). This reaction to the removal of the Japanese was vastly different from the media's actions in other parts of the West Coast. In San Francisco, the media created hatred toward the Japanese. Kazuo Ishimitsu remembered the newspapers:

"Well, if you read the Hearst papers or any of those, or listen to the radio programs, you know that they created hate....And because of that, they tell you you're 'slant-eyes' and all that, it was so predominant, 'yellow-belly,' that kind, it does affect the young mind" (Pak 130).

This hatred seeped into the surrounding communities. Japanese American students in schools noticed changes in the attitudes of their fellow white students. Some Chinese even began wearing buttons saying, "I am Chinese," in order not to be associated with the Japanese. Other students were abused by former friends who allowed the propaganda to influence their opinions of the Japanese (Pak 130-134).

On March 30, 1942, at 11:00 a.m. the Island Japanese Americans boarded a ferry to Seattle. From Seattle, they rode a train to central California (UW article). On that day, many Island people showed their support by heading to the ferry dock and saying their final goodbyes. Students at Bainbridge High left their classes, and adults took the day off to watch as their companions boarded the ship without protest or resistance. This day still represents the saddest day of many persons' lives.

"We said goodbye, With a great deal of worry. Everyone cried and apologized, And said 'We're so sorry!' They did come back, After years of strife, Now 54 years later I recall, The saddest day of my life" (Ritchie).

By contrast, in the following months Japanese Americans were uprooted from other communities in Washington without public acknowledgment from their neighbors, who were either indifferent or glad to see them go (Neiwert 140-141).

Once the Bainbridge Islanders reached their first internment camp in faraway Manzanar, California, they did not show anger or malice to the authorities or government; they wished to show continuing loyalty by being extremely obedient and compliant. In Manzanar, the Islanders found themselves to be the outsiders. Of the 10,000 internees, the Islanders made up about 275 of them. (Another 25 Islanders had voluntarily left the West Coast before Order No. 1 was issued.) Walt Woodward criticized the choice of Manzanar for them.

"That is like putting one Washington apple in a crate of California lemons. The Review has a pitiful file of letters – as do many Islanders – from our evacuated residents, telling how utterly foreign they have found some of their California 'neighbors' to be"(Woodward: Apples and Lemons).

The Islanders noticed that, while they had the same ancestry as the Californian internees, and looked the same, they were quite different. They felt extremely isolated and did not mix well with the Californian Japanese. During a riot at the camp, the Bainbridge Island Japanese displayed their loyalty by not participating. They hoped that they would be relocated to another camp where they would fit in better. The Islanders were unique in their unwavering obedience to the camp authorities (Woodward: Apples and Lemons).

Woodward used the Bainbridge Review as a unique channel of communication for the internees. He created an "Open Forum" column in his newspaper and published articles from Japanese internment camp correspondents. These articles humanized the Japanese's situation by reporting births, deaths, graduations, marriages, Army enlistments, and the location of those Islanders who were allowed to work or attend school outside the camp. This allowed Island readers to follow the misfortunes of their former neighbors. The Island readers responded by expressing their support for Woodward's activities. "I would like to take this opportunity to congratulate you on your front-page editorial in last week's Review on the Japanese evacuation problem. It was excellent and, I believe, well expressed the attitude of the majority of Islanders" (Halvorsen).

Woodward made sure his newspaper was also a channel of communication to the internees. He sent copies of the Review to the camp each week. In this fashion the internees were able to keep informed about events and activities in their former community such as sports, the activities of churches and clubs, and election results. This helped the internees remain mentally connected to Bainbridge Island (Ohtaki). Paul Ohtaki said it best: "Walt Woodward wanted us to feel like we had a home to come back to" (Visible Target).

World War II ended on September 2, 1945, with the unconditional surrender of the Empire of Japan (Kashima 221). After three and half years of internment, the Japanese Americans from Bainbridge Island wanted to return home, but they were uncertain what the future held. Woodward used the Bainbridge Review to promote the idea of return.

Even in the close-knit community, there was some public resistance. Lambert Schuyler was the leading advocate for the continuing exclusion of the Japanese. He was an open racist and tried to stir up the community to oppose the return of the Japanese. He verbally attacked anyone who was in favor of the Japanese's return and passionately argued for their exclusion from the Island:

"Whether Nisei or not, whether loyal or not, Japs who return to Bainbridge will be met by insult and abuse, if not worse ... The Jap is not assimilable ... Unless we are prepared to love and intermarry with the Japs we may expect more Nisei to be traitors at heart ... . We don't want any Japs back here ever" (Schuyler).

A meeting was held on the Island on November 3, 1944, called by Schuyler to stir up opposition to any return of the Japanese to Bainbridge. About 200 people attended. It was later recognized that the reason for such a high number was mere curiosity. For example, even Millie Woodward, Walt's wife, attended the meeting to see what was going on. At the next meeting called by the agitators, on November 24, 1944, only 34 persons attended, including many children (Swain 124-126 ). In fact, by the time the internees arrived, there was no visible opposition to the Japanese American Islanders' return and they were welcomed.

The return of the Bainbridge Island Japanese was facilitated by a public welcome from their former friends, neighbors, and business associates. "When the interned Japanese Americans returned to Bainbridge, 'there wasn't one damned incident, Woodward recalls. He claims no credit, but others know that his treatment of the tragedy of internment was largely responsible" (Hannula).

The internees did not come back as strangers. When Gerry Nakata returned, "one of his closest white friends from high school met him at the ferry dock to welcome him home. Back on the Island, Nakata felt no animosity and he and his brother resumed their family's grocery business" (Swain 154). They partnered with the Loveriches to open a grocery, butcher, and florist operation. Myrtle Norman had looked after her longtime friend Shigako Kitamoto's home and property. Felix Narta had managed Shigako Kitamoto's strawberry farms and turned them back to her; she rewarded him with a piece of property on which to build a home. Bainbridge Gardens Greenhouse & Store, which had been a showcase, was ruined from neglect and theft during the war, but the two Japanese owners' families divided the property and began life anew on the Island. Over one-half of the Japanese-American families who had been exiled from Bainbridge Island returned to the island after the war (Moriwaki 4). They were reintegrated into the community and reclaimed their rightful places in society (Visible Target).

The experiences in other Washington communities were not so triumphant. For example, in Bellevue, agitators called a meeting to express opposition to the return of their former Japanese American neighbors, and over 500 persons attended. The local business interests did not want to see the Japanese return their fields to strawberry production, hoping to purchase and redevelop the lands as office parks and residential suburbs for their own profit. The Issei and Nisei who had been exiled from Bellevue did not have a local champion like Woodward, and had fewer and weaker bonds to their former neighborhood. Consequently, out of the 60 Japanese American families in Bellevue at the time of their removal, only 11 returned after the War (Neiwert 214).

Through perseverance and courage, the Bainbridge Island Japanese were able to recover more quickly and completely from the tragedy of internment after the war. In a country filled with people of all nationalities, a melting pot, the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor caused an unjustified suspension of constitutional rights. The tragedy of uprooting legal aliens and U.S. citizens of Japanese descent without legal warrants, hearings, or court orders demonstrates the vulnerability of freedom in America in time of war. The loss of economic livelihood and prosperity suffered by these victims was not compensated in any significant way. (In 1988, finally, Congress passed a law, signed by President Reagan, requiring the federal government to send, to each surviving internee, a letter of apology and a payment of $20,000.)

The government's ability to turn a blind eye toward human rights when they conflict with the goal of national defense is an important lesson for today. The United States government is waging a "War on Terror" against Muslim extremists. Even today, the government can abuse the rights of Muslim Americans for national security. As in 1941, a vocal press is needed to protect those rights.

Relocation was a tragic injustice. Individual human determination and neighborly compassion helped the Islanders heal the wounds of this injustice, maintain their ties to this community even while exiled, and regain their standing on Bainbridge Island after the war ended. Other Japanese American communities were not as blessed, and some never recovered from the effects of exile. One should never forget the lesson of this tragedy, that even the United States government is capable of abusing basic citizen rights in the name of security (Rehnquist 3-8). One should also remember the lesson of the triumph achieved by Bainbridge Island, which is that individual courage and a strong sense of community loyalty can overcome such abuse.