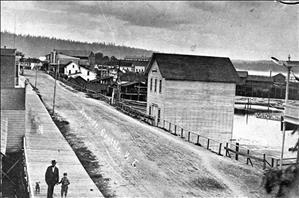

On June 8, 1876, the Seattle City Council passes an ordinance for the first ever large-scale grading of a Seattle street. For the next 11 months, contractor George Edwards and his crews use picks, shovels, and wheelbarrows to smooth out Front Street and make it a gentle grade from James Street north to Pike Street. At the time Front Street (which will later be renamed First Street) runs right along the waterfront and is one of Seattle's main commercial thoroughfares.

Making Molehills out of Mountains

Seattle's first stab at making a molehill out of its mountains began with city council passage of Ordinance 112, "To Provide for Grading Front Street." The measure described the bidding process and specifics of what would be done, and stated that adjacent property owners would have to pay for the work. When the council opened bids in July, George Edwards was awarded the right to cut and fill Front Street from James to Pike, even though the "Chinese firm of Quong Coon Lung" made the lowest of nine bids -- $9,000, which was $1,000 lower than Edwards's price (Post-Intelligencer, July 8, 1876).

This would not be the last time that racism played in a role in the project. The Seattle Post-Intelligencer complained that Chinese laborers who worked for Edwards were "puttering away at it tediously" while asserting that white workers were "busily engaged in the work with picks and shovels" (Post-Intelligencer, September 19, 1876). Moreover, the paper claimed that whites would save their earnings and eventually use them to buy a lot, build a house, or invest in land, but insisted that Chinese workers would only help Chinese companies and then send what money remained back to China. Eventually the paper reported, "We were much pleased to notice yesterday that Coolie labor had been dispensed with on Front Street" (Post-Intelligencer, October 8, 1876).

After getting his contract from the city council, Edwards began grading on July 13, 1876, in front of Henry Yesler's property between James Street and Cherry Street. The city's work plan required Edwards to create grades ranging from 4 percent to 7 percent, as Front Street rose from 12 feet to 107 feet above sea level. To keep back Elliott Bay, whose waters washed ashore just below Front, he would have to build log cribbing up to 27 feet high along the western edge of the street. In mid-August, City Surveyor Phillip G. Eastwick estimated that the project would require 26,000 cubic yards of dirt. Excavations along Front Street would provide two thirds of the material, with the rest coming from cutting down the side streets running east from Front. Eastwick also raised the project cost to $12,000.

Edwards employed up to 90 men and used 20 mules and horses. Using picks, shovels, carts, and wagons, the workers made their deepest cut of 25 feet at Spring Street and their greatest fill, an addition of eight feet, between Marion and Madison. They built extensive cribbing along the shorefront using cedars harvested from the woods behind Belltown, then more or less a suburb of Seattle. They raised many houses on stilts -- some up to 12 feet -- which would eventually be supported by fill, and left others high above the road, which required homeowners, such as Arthur Denny, to build what was described as a "prevent wall," to stop their houses from sliding.

Slow Going

Work did not always go as planned. Edwards had to rebuild an extended section of cribbing because he did not use long-enough logs to tie the cribbing into the embankment. When the rains came in October, runoff washed away fill, made deep gullies, and caused sliding. In some cases, the streets were "literal cesspools" (Post-Intelligencer, November 22, 1876). By January, work costs had increased to $13,000.

Seattle's typical winter rains continued to hamper progress, causing delays that extended into April. In March the P-I reported that the work would be finished in a week or so, but it wasn’t done until May. Nonetheless, the paper claimed that Front Street was now "one of the most pleasant and excellent thoroughfares to be found in any city this part of the coast" (Post-Intelligencer, March 28, 1877)

To the editors of the P-I and Seattle's other newspaper at the time, the Daily Pacific Tribune, street grading was essential to what came to be called "Seattle Spirit," the city's striving, pick-itself-up-by-its-bootstraps, can-do attitude. An editorial in the Pacific Tribune noted that "any one with half an eye can see the good already accomplished ... [it is] stamping the growth and business of the city as the most enduring, desirable character" (September 27, 1876). Said the P-I, the grading "bespeaks enterprise; shows that we mean business; that we mean to stay here" (October 15, 1876). Just 25 years after its founding, Seattle was a city to reckon with. Nature be damned, if roads blocked the pursuit of manna then they would be dealt with accordingly.

And once local leaders realized that they could tame the topography, they went at it with a passionate zeal. On Mill Street (now Yesler Way) workers made cuts of up to 20 feet as it climbed east and one block south on Washington Street, the men dug up stumps and burned huge logs to push that road further east. Within a few years, the city council passed ordinances for grading Second, Third, Fourth, Madison, Marion, and Commercial streets.