On June 5, 1876, Eldridge Morse (1847-1914) dedicates the Snohomish Atheneum beginning with the words, “Around me are many familiar faces of brave, true-hearted pioneers, who, a few years ago found this valley a wilderness, uninhabited by civilized beings.” His address at the laying of the cornerstone will be published in his own newspaper, the Northern Star, the following Saturday. Located at Snohomish's central intersection of Avenue D and 1st Street, the two-story building represents the evolution of a literary and cultural organization begun in 1873 when the elite of early Snohomish pooled their books to establish the county’s first lending library of some 300 volumes. Ultimately hard times will result in the building's being sold for use as a saloon. It will be dismantled and sold for scrap in 1910.

Flight from Cultural Insularity

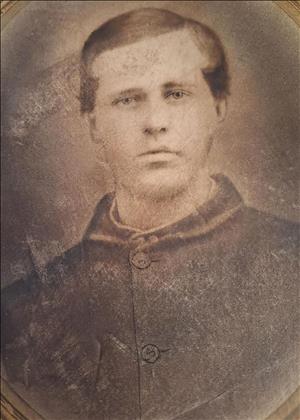

The two guiding lights of Snohomish’s Atheneum Society arrived in town a month apart. Eldridge Morse was born in Wallingford, Connecticut, on April 14, 1847, into a family descended from the early Puritan settlers of Massachusetts, and boasting of a branch in the family tree holding Samuel F. B. Morse, inventor of the Morse code. Trained as a lawyer at the University of Michigan, he and his young family migrated to the Pacific Coast, landing in Port Madison, Kitsap County. On a visit to Seattle, Morse happened to meet E. C. Ferguson (1833-1911), considered the founder of Snohomish, who talked him into moving his family to the riverside settlement. Morse arrived in Snohomish on October 26, 1872, where he remained until his death January 5, 1914.

The exact date in November 1872, that Albert Folsom (1847-1885) arrived in Snohomish has not been found; evidently, he was not the chronicler of his own life that Morse was. Born in New Hampshire July 14, 1827, he was exactly 20 years older than Morse, who wrote a moving elegy for The Eye, Snohomish’s second newspaper, upon Folsom’s death on May 15, 1885, and from which we learn the outline of a most interesting life.

Folsom interrupted his enrollment in the Classics Department at Harvard University to travel with his botany professor for study in Peru and other parts of South America. Earning a degree in Classics upon his return, Folsom immediately entered the medical school to earn a second degree from Harvard. He was commissioned as a second assistant surgeon in the U.S. Infantry in 1948, and assigned to serve under Robert E. Lee, the beginning of a long stretch of military service that included an assignment with the Secret Service in Costa Rica. His first wife died many years ago, and upon resigning his military commission, he married a Wisconsin woman, but it was a union that “proved very unfortunate,” Morse writes. It seems that the first medical doctor of Snohomish County arrived with a broken heart and no ambition to “accumulate property or secure a place or position for himself’’ – he offered his medical services for voluntary payment.

Together, Morse and Folsom proposed the idea of the Atheneum Society to Snohomish’s elite, and its establishment in late Autumn 1873, has been described as “fuel [for] their flight from [the] insularity” of frontier life (Grover).

From Library to Live New Paper

The collection of books with titles as diverse as The Works of Flavius Josephus, The Arabian Nights, even Darwin’s Descent of Man, seemed only to stir the appetite for more intellectual interaction among members of the society; so, in January 1874, the group launched a handwritten newsletter called The Shillalah to be read aloud at the meetings and circulated among interested members.

It is assumed Eldridge Morse served as first editor, although no names are listed, but it seems to be his style to give the journal the subtitle, “A Live New Paper, devoted to Art, Science, Literature, and General News, regularly appearing now and then, designed to promote harmony, sociability, good nature, and good behavior.” Under the guidance of both men, however, the theme of rejecting the cultural isolation of frontier life wove self-consciously in and out of the content of the first issues – like the home-made binding of thread holding the chapbook together.

Snohomish Women's Voices

Once initiated by the men, as the old story goes, the continuous operation of the journal was eventually assumed by the women. In short order they changed the name to The Athenea. The tone and content also changed to include more news of the community, comments on world events, and direct-from-the-heart essays, some about unfair treatment by husbands. The uncorseted women of Snohomish expressed expectations of freedom from the strict codes and mores of the East. Advocating more than women’s rights, the writers called for greater temperance in their city, a common call in frontier towns.

The women also recommended to the men dancing as a healthier form of recreation than drinking and playing poker. Snohomish’s social life did expand along with the population to include dances, even an annual masked ball. After the Atheneum building was sold, these dances were held there, though the building was now called the Cathcart Opera House. In newspaper articles and advertisements it was still referred to as Atheneum Hall, perhaps as a way to skirt around the seedy connotations that the label opera house held in frontier communities.

Snohomish County's First Newspaper

The success of the handwritten newsletter encouraged Morse and Folsom to establish the first newspaper of both town and county. Morse traveled to Olympia to purchase a used printing press, brought it back via steamship, then taught himself how to set type. The first issue circulated up and down the one-street-town on January 15, 1876. The last was issued on May 3, 1879. In his address to dedicate the Atheneum on June 5, 1876, Morse asked rhetorically, “What is this community? How does its spirit harmonize with the tendencies of the age? And what is the work we have in hand by which we hope to ‘leave behind us, footprints on the sands of time?’”

End of the Atheneum

Unfortunately, economic times slowly soured, leaving the nascent cultural organization little choice but to accept the offer of Isaac Cathcart (1845-1909) to purchase the unfinished building. Cathcart, a logger turned entrepreneur, opened a store to serve the growing logging industry, and an upscale saloon that he called the Cathcart Opera House, which is how it is most likely remembered today. Over the ensuing years, Cathcart made and lost a fortune, and ended up offering his empty opera house to the town’s first militia for drills until their own Amory was ready. The cultural landmark of early Snohomish was listed as vacant on Sanborn Insurance maps just before it was dismantled for scrap in 1910.