The Civil War started with the Confederate shelling of Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor, South Carolina, on April 12, 1861. Washington Territory was just under eight years old and more than a quarter century away from statehood. The most populous town in the territory was Walla Walla, with 722 people, including 17 Indians and one African American. The population of the entire territory, which until 1863 included all of present-day Idaho and part of Western Montana, was just over 11,500. (This count excluded most Indians.) The nation's far Northwest was a continent away from the blood-drenched battlefields of the War Between the States, slave-free (with only one or two known exceptions), and populated by men and women intent on making new lives in a new land. An indeterminate number of the territory's men went east to voluntarily enlist, most on the Union side, although the siren song of states'-rights supremacy drew some to fight for the Confederacy. Others volunteered or were conscripted for the newly mustered First Washington Volunteer Infantry, which never saw battle. Many in the territory were ambivalent on the issue of slavery, but strongly in favor of preserving the union. Although not one shot was fired in anger in Washington Territory due to the war, nor any property destroyed, the people of the Northwest, in common with the rest of the nation, were deeply affected by the outcome of this most lethal of American conflicts.

Slavery in the Territories

In 1787, 18 years before Lewis & Clark's Corps of Discovery Expedition reached the Pacific Ocean, the United States Congress passed the Northwest Ordinance establishing rules of governance for "territories north of the River Ohio." One of its many and detailed provisions mandated that the subject territories were to remain free of slavery. More than 60 years later, the Organic Act of 1848 extended that prohibition to Oregon Territory, which then included all of what would much later become Washington state. But the ban on slavery did not mean that the territories were free of racism -- both as a Territory and as a State, Oregon sought to bar free blacks from residing within its borders.

When Washington Territory was carved off from the unwieldy Oregon Territory in 1853, it remained subject to the law prohibiting slavery, but it did not copy Oregon's attempts to bar free blacks from settlement. In the years leading up to the Civil War, former slaves and free black men and women seeking new lives in the Northwest had little choice but to settle north of Oregon. This they did, albeit in small numbers -- the 1860 federal census counted only 30 African Americans living in Washington Territory, 26 men and just four women.

In 1857 the U.S. Supreme Court, in the infamous Dred Scott decision, ruled that Congress had no power to prohibit slavery in the territories. Washington's Territorial Legislature passed a resolution expressing its approval of the decision, but the court's ruling turned out to have virtually no practical effect in the far hinterlands of the Northwest. There was little if any public support for allowing slavery in the territory, despite the fact that a significant number of those settling the area had come from the slaveholding states. Unlike in the intensively agricultural South, there was simply no need for slave labor in the territory, regardless of one's opinions about the morality of what had come to be called the "peculiar institution."

In an odd anomaly, although slavery was forbidden in Washington Territory before 1857, slaves were not, providing they had not originally been enslaved or bought and sold within its boundaries. Shortly before the Civil War began, there was known to be one slave in the territory and reports of a second. The latter was a woman, rumored to reside with her "owner" at Fort Steilacoom; little information about her has survived. But the existence of the other, a young man named Charles Mitchell, is well documented.

Charles Mitchell: Slave or Free?

Charles Mitchell (1847-1876?) was born into slavery on a plantation in Maryland, the son of an African American mother and a white father. His mother, personal servant to a child of the Gibson family that owned the plantation, died of cholera in 1850. The Gibsons assumed responsibility for her young child's care, and in 1855 they arranged for Charles to travel to Washington Territory with a Gibson in-law, James Tilton (1820-1878), recently appointed as the Territory's first surveyor general.

Young Mitchell's legal status in Washington Territory after the Dred Scott decision was open to dispute. As a matter of law, after the Supreme Court's 1857 ruling, slavery was legal in all American territories, at least until statehood was achieved and a vote taken on the issue. Yet, with apparently just the two exceptions, slaves were not kept in Washington. In 1860, when Mitchell was induced to stow away on a vessel heading for the Crown Colony of Victoria on Vancouver Island, the question of his status -- property or free person -- suddenly became a very public issue.

Victoria had a large black community in 1860, estimated by some to be as high as 25 percent of the population. A black man visiting Olympia from Victoria noticed Mitchell and over the course of several conversations convinced him to flee to Canada, where, he was told, he would be without question free. He was hidden in the pantry of the mail steamer Eliza Anderson, but was discovered there and held under lock and key until the vessel docked in Victoria. It was the intent of the ship's captain, John Fleming, to return Mitchell to the custody of Tilton on the return trip.

Henry Crease (1823-1905), a Victoria barrister, took up Mitchell's cause and obtained a writ of habeas corpus compelling his release from the ship. After spending one night in the Victoria jail, he was given over to the care of the town's black community. Both James Tilton and Captain Fleming filed protests with the colonial government, to no avail. In the view of Canadian authorities, Canada was slave-free, Mitchell was in Canada, and that was that. Appeals by Tilton to the government in Washington D.C. went unanswered, and the lad remained on Vancouver Island, where he reportedly drowned in 1876.

The Mitchell case was a cause célèbre both north and south of the border. The nature of the relationship between Mitchell and Tilton was ambiguous, as historian Lorraine McConaghy has described:

"James Tilton was called a master, an employer, a guardian, an owner, and a man 'like a father to [Charlie].' Conversely, Charles Mitchell was called a slave, an employee, a ward, property, and '"like a son to [James Tilton]' ... . In the last analysis, Charles Mitchell was owned and was not free to come and go as he pleased — severed from his family, a black child in a white household" ("Charles Mitchell, Slavery, and Washington Territory in 1860").

The territorial press coverage of the Mitchell case shows that Washington Territory, although virtually free of slaves, was not free of a racist and paternalistic attitude towards African Americans. In a long recounting of Charles Mitchell's escape and the ensuing legal actions, the Territory's oldest newspaper, the Olympia Pioneer and Democrat, closely tied to the Democratic Party, let the veil slip:

"As with most mulattoes, he lacks stability, and has not the faithfulness and gratitude which distinguishes the pure African, and was remarkable in his mother's people for the several generations they have been held in Maryland" ("Fugitive Slave Case").

The Election of 1860

Going into the presidential election of 1860, America's political parties were sharply divided on the question of slavery's place in the nation's territories. The sitting president, James Buchanan (1821-1875), was a pro-slavery Democrat, but his party had split into two factions on the issue. One believed slavery should be decided by a vote of the people of the individual territories, and it nominated Stephen A. Douglas (1813-1861) for president in 1860. The other faction, led by Buchanan's vice-president, John C. Breckinridge (1821-1875), believed that the federal government should protect the right of slaveholders to settle in the territories. Breckinridge was selected to carry its banner in the presidential race.

The Whig Party, once the main opposition to the Democrats, had been torn apart in the 1850s by internal disputes over slavery. Its remnants, together with former members of the also-defunct Know Nothing Party, formed the Constitutional Union Party to contend in the 1860 election. Its platform, if such it could be called, promised to ensure the preservation of the union by simply ignoring the slavery issue. John Bell (1796-1869), a former Whig from Tennessee, was its nominee for president.

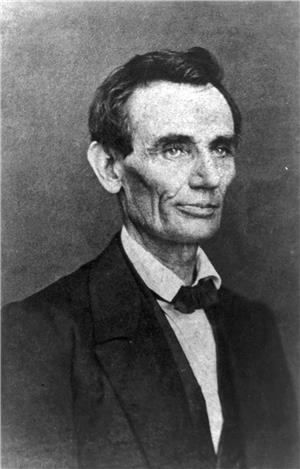

The Republican Party, the fourth to enter the race, was just six years old and had first contended for the presidency in the 1856 election, without success. The party was founded on opposition to the spread of slavery into the territories, but not its complete abolition. In one of the most fateful moves in American political history, it nominated Abraham Lincoln (1809-1865) as its candidate. With four men in the race, Lincoln won the 1860 election with just 39.65 percent of the popular vote, but still defeated his closest rival, Douglas, by nearly 500,000 votes.

Lincoln had neither threatened nor promised to end slavery, but he was firmly opposed to its further expansion. This alone was enough to tear the union apart. South Carolina was the first state to secede, in December 1860. Before Lincoln was inaugurated on March 4, 1861, South Carolina had been followed by Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, and Texas. Virginia pulled out of the union in April 1861, Arkansas and North Carolina in May, and Tennessee in June. When the dust settled, there were 23 states left in the original United States and 11 in the new Confederate States of America.

Washington Territory and the Issue of Slavery

Residents of Washington Territory could not vote in the 1860 presidential election, nor did they have the right to participate in the parties' nominating conventions, but there was no lack of opinions on the nation's pressing issues. News was long-delayed at a time when neither telegraph wires nor railroad tracks had yet arrived, but word of what was going on in the wider country eventually trickled through.

The Democratic Party dominated Washington's territorial politics in the years leading up to the Civil War, and patronage ensured that appointed government officials reflected that domination. The Republican Party was growing, having gained new members from the collapsed Whig Party, but it remained in the minority. Territorial Democrats and Republicans generally hewed to the national parties' lines on the slavery issue, but without the passion and anger that reigned in the East. Typical for the day was the attitude of the Democratic Pioneer and Democrat, printed in Olympia. Its editorials trumpeted the pro-slavery cause, but noted that it had little significance in the territory, where the issue had "long since been settled by latitude and climate" ("Our Policy").

What was of significance to all was the threat that the slavery battle posed to the cohesiveness of the nation. Even before the election of 1860, the Pioneer and Democrat warned:

"It is the firm settled conviction of the public mind that we are approaching, nay, have reached a crisis in political affairs, compared with which all former ones were as gentle gales to the destroying whirlwind" ("The Present Position of the Parties").

But the newspaper left no doubt where its sentiment lay on the core issue:

"no force of argument can dislodge the simple but powerful fact, that the abolition of slavery, except by the lapse of time and the direct destiny of man, could confer no blessings on the white or colored race in American" ("The Present Position of the Parties").

The Republican Party was slowly growing in influence in slave-free regions, and the election of Lincoln was greeted with joy within its ranks. A Republican newspaper, the Washington Standard, was started in Olympia in 1860, espousing the anti-slavery views of the national party and promising to "do battle for the advancement of free territory, free labor, free speech, and free men" ("The Secession Crisis and the Frontier," 422).

But what of the people? What did they believe? There were no public opinion polls in 1860, at least not in Washington Territory, so reliance must be placed on what can be gleaned from the partisan press and local political developments. From these, it can be seen that moderation was more evident in the territory than in the overheated East. After the election, Republicans and "Douglas Democrats" in the lower house of the Territorial Legislature formed a coalition, much to the dismay of pro-slavery "Breckinridge Democrats." The Republican position -- to allow slavery to continue in the states in which it existed while barring its further spread -- seemed to most nearly reflect public sentiment.

There were, of course, strict abolitionists in the territory, fueled by moral outrage at the very idea of human bondage, but the consensus appears to have been much more nuanced. In January 1861 the Territory's first governor, Isaac Stevens (1818-1862), a pro-slavery Democrat who had supported the candidacy of Breckinridge and was serving as Territorial representative in Washington, D.C., wrote an open letter to the people that was published in the Pioneer and Democrat. Using the single name "Jefferson," Stevens wrote:

"the hope is cherished that the position you occupy as neutrals — it may be as an arbiter — to the irritating contest between north and south, will enable you to exercise a beneficial influence upon both sections; on one hand checking aggression, and on the other restraining rashness, and so helping to extricate the Union from a danger which no rational man can contemplate without a shudder" ("Correspondence From the States").

There clearly was deep ambivalence about slavery in Washington Territory, itself virtually untouched by the scourge. Should it be abolished throughout the nation? Should it be retained, but only where it already existed? Should it be allowed to spread with the settlement and eventual statehood of the territories? Should the issue be determined state by state on a vote of the people? All views found support, but none dominated.

Washington Territory and the Issue of Secession

On the issue of secession, there was little such ambivalence. The economic imperative used to justify slavery in the South was absent in Washington Territory. What people were concerned about was the sundering of the United States into separate and warring nations. Although it was still decades away, the settlers in the territory looked forward to eventual statehood, and the overwhelming majority wanted the country they hoped to join to stay intact. If permitting the continuation of slavery was the cost of maintaining the union, then it was considered by many to be a price worth paying. But allowing the Southern states to secede, for any reason, was unacceptable, and when first South Carolina and then 10 others did just that, most in Washington Territory threw their full support behind Lincoln and his vow to preserve the union whatever the cost.

The evolution of Isaac Stevens on the issues is instructive. Filling in for an absent delegate from Oregon State, he had voted for Breckinridge as the Democratic Party's pro-slavery presidential nominee at the 1860 convention. He actively worked for his election, even though the residents of the territory he once governed and now represented in Washington, D.C. could not vote. When Breckinridge lost and the slaveholding states seceded one by one, Stevens returned to Washington Territory to seek re-election as its delegate to the national government, hoping to work to preserve the Union. When thwarted, he first tried to put together a coalition to work for a peaceful resolution to the growing conflict. When this too failed and war began, Stevens enlisted in the Union Army, where he fought with distinction and died in defense of the Union cause.

The Pioneer and Democrat, despite having strongly supported Breckinridge, also opposed secession:

"the cheers for a Southern Confederacy ... oppress the heart of the patriot, while they dimly shadow forth long years of unknown trouble ....

"In the meantime, as we await the result of this revolution, let us cherish toward each other kind and magnanimous feelings, — and though we hail from different sections, let us not forget our duty to our country. We are for Union now and forever, and recognize no disunionist as a fellow partisan" ("Secession").

Another staunchly Democratic newspaper, the Port Townsend Register, was also adamant:

"Whilst we regret the election to the Presidency of one whose principles are aggressive of Southern rights, we maintain that it is the patriotic duty of every good citizen to stand by that preference which the Nation has expressed conformably to the provisions of the Constitution. We, therefore, disavow all sympathy with those who place themselves in the attitude of Rebels against the powers that be" ("The Secession Crisis and the Frontier," p. 427).

Although the overriding desire to preserve the Union seemed paramount, there was one interesting historical sidelight as the Union started nonetheless to unravel -- the revival of an earlier proposal for the creation of an independent nation, the "Pacific Republic," encompassing all lands west of the Rocky Mountains. But, as had happened when it was first proposed in 1855, the idea found little public support and lived on only as the hobbyhorse of a small fringe.

War and Rumors of War

In the tense months between the November 1860 election and Lincoln's inauguration on March 4, 1861, the press and political parties of Washington Territory tried mightily to be the "beneficial influence" that Stevens had hoped for. But they were far removed from the action, largely insulated from the passions that raged back East. While the territorial public was calling for compromise, states in the East, both north and south, were preparing for war. Fed by false rumors that Lincoln was determined to abolish slavery, Southern states continued to secede and arm themselves for combat. The Pioneer and Democrat, faced with the reality of serial secessions and the certainty of war, briefly and vainly reversed its position, calling for recognition of the Confederated States "not as a matter of Constitutional right, but as a matter of principle" ("The President's Inaugural").

On April 12, 1861, Confederate forces rained artillery fire upon the Union army's Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor, South Carolina, the first state to secede. The Union commander, Major Robert Anderson (1895-1871), was forced to surrender a day later. The Battle of Fort Sumter officially started the Civil War, the bloodiest by far in United States' history. There was no accurate contemporary accounting of the dead and wounded, but most postwar estimates put the number killed at more than 618,000. A study completed in 2012 placed the toll 20 percent higher, at 750,000. Many more men died from disease than from wounds, and in contrast to modern American wars, the dead greatly outnumbered the wounded.

News of the war's start reached Portland on April 28, 1861, carried by the steamship Cortez. It then percolated slowly up the coast by land, with the first mention in a Washington Territory newspaper coming on May 2, 1861, when Steilacoom's Puget Sound Herald, on page 2, announced:

THE WAR COMMENCED!

Battle and Surrender of Fort Sumner

A day later, the same news was announced in the Pioneer and Democrat in Olympia under a stack of emphatic headlines ("Attack on Fort Sumter"). It appears that the news then reaching the territory was fragmentary, overlapping, and one step ahead of the typesetters. In the same edition, on page one, the Pioneer and Democrat noted:

"A thousand rumors are in circulation, the principal of which indicates that Fort Sumpter [sic] will be attacked in the course of a few days" ("By Express and Overland Mail").

It took another week for the news of war to reach Port Townsend, where it was announced in The North-West newspaper. From the territory's towns, the dire reports slowly spread by overland mail and travelers' mouths.

Mobilization

In response to the secession crisis, on April 15, 1861, President Lincoln issued a proclamation to:

"call forth the Militia of the several States of the Union to the aggregate number of 75,000, in order to suppress said combinations, and to cause the laws to be duly executed ... ." ("Commentary: Lincoln's Proclamation").

Although the proclamation referred only to "the several States of the Union," Washington Territory's acting governor, Henry M. McGill (1831-1915), on May 10, 1861, took steps to activate a Territorial militia:

"deeming it expedient that the militia of the Territory of Washington should be placed in readiness to meet any requisition from the President of the United States or the Governor of this Territory to aid in 'maintaining the laws and integrity of the National Union,' I do hereby call upon all citizens of this Territory capable of bearing arms and liable to militia duty, to report immediately to the Adjutant General of the Territory and proceed at once to organize themselves into companies, and elect their own officers ... ." ("Acting Governor Henry McGill issues a proclamation ... ")

Barely one week later, Isaac Stevens offered his services to the Union cause and joined the fray. He would not receive a command until August 1861, after which he distinguished himself in battle. Promoted to brigadier general, he lost his life at Chantilly, Virginia, in September 1862.

Several other officers who went on to fight for the Union or the Confederacy had before the war served at Washington Territory's Fort Vancouver. On the Union side, these included General Grant, General Philip Sheridan (1831-1888), General George B. McClellan (1826-1885) (who, before Grant's appointment, commanded the Union Army), and Brigadier General Joshua Sill (1831-1862). For the Confederates, the most noted was General George Pickett (1825-1875), who earned fame, or infamy, for the failed "Pickett's Charge" at the Battle of Gettysburg on July 3, 1863.

Any Volunteers?

Governor McGill's call to arms did not bring forth a stampede of patriotic volunteers. His proclamation merely "call[ed] upon" citizens to enlist, and did not command it. The war was remote and news was late and sparse. There was still significant sympathy for the Southern cause, and the full ramifications of secession may not yet have penetrated the public consciousness. A rather typical view of the situation is set forth by an early historian of the territory:

"They had long heard of the threats made by the secessionists to break up the Union, but did not regard them as serious. They were so far away that only the last and feeblest reverberations of the guns from Fort Sumpter [sic] reached them. The blare of trumpet, and soul-stirring throb of drum, that sounded so continually in the ears of people in the Eastern States, hardly penetrated to their quiet homes, and when they did it hardly seemed probable that any patriotic response on their part, if made, could be of any benefit.

"The Democrats had always been in the majority in the territory. All the governors so far had been Democrats, appointed by Democratic presidents, and all the delegates in Congress had been Democrats, and had been elected by considerable majorities. The majority had, therefore, long been opposed to any interference with slavery, and inclined to sympathize with the slaveholders, as against the abolitionists ... . The majority accordingly were but little inclined to march across the continent to engage in the war on either side, and the minority probably did not, for some time, comprehend that the attack on Sumpter had changed the issue from one about slavery, to one about union or disunion" (Snowden, Vol. 4, 103-104).

Despite this lack of enthusiasm, on May 14, 1861, Adjutant General Franklin Matthias of Seattle issued an order appointing men in each of the territory's 22 counties to identify and record "all persons liable to Militia duty" ("Washington Territorial Militia In the Civil War," p. 14). This achieved some results, and county militias were formed that carried such names as the Puget Sound Rangers, the King County Rifles, and the Jefferson Union Guards. But the response was far from overwhelming; in the first weeks after the call to arms, only six of the Territory's 22 counties had responded and the head count of volunteers stood at just 361, most of whom had no weapons fit to fight with.

The primary role of the territorial militia was to replace those soldiers from the regular Union army who were being called to the battlefields of the East. This exodus led to the immediate closure of several forts in the territory and in Oregon, including Fort Cascades, Fort Yamhill, Fort Townsend, and Camp Chehalis. By mid-summer 1861, 3,361 federal troops had been removed from the army's Department of the Pacific and sent east.

Despite the public's tepid response to calls for volunteers in Washington Territory, there was some resistance from Territorial officials when, in October 1861, it was announced that California volunteers would be sent north to replace soldiers who had been called east. J. G. Hyatt, the militia representative for Whatcom County, wrote to Governor McGill:

"We learn with regret that the Federal Government have determined to garrison the military posts of this Territory (made vacant by the withdrawal of the regular troops) by a Volunteer force from California ... . It looks very much like a slight to the people of this Territory and that their loyalty is questioned" ("Washington Territorial Militia In the Civil War," p. 18)

In another attempt to sign up troops, Colonel Justus Steinberger was sent from Washington, D.C. in October 1861 "to raise and organize a regiment of infantry in that territory and the country adjacent thereto, for the service of the United States, to serve for three years, or during the war ... . ("Washington Territorial Militia In the Civil War"). Before his search was even well underway, Union military authorities were expressing doubt about its efficacy. A December 10, 1861, letter to the army's adjutant general from Brigadier General George Wright, commander of its Department of the Pacific, said:

"I anticipate considerable difficulty in raising a regiment of Infantry in that country. The sparse population and the intense excitement caused by the recent discovery of very rich gold mines may render it impossible to obtain such a large number of men" ("Washington Territorial Militia In the Civil War," p. 19)

Wright's concerns proved valid. Steinberger found few volunteers and received little official encouragement. Resolutions of support for the Northern cause were introduced in both houses of the Territorial Legislature, but did not pass. Steinberger moved on to California and eventually managed to raise a regiment of volunteers, named, somewhat oddly, the "First Washington Volunteer Infantry." Only two of its 10 companies were recruited from north of California, and one of those was composed primarily of men from the state of Oregon. Only a single unit, Company K, was made up exclusively of men from Washington Territory. This company rarely left Fort Steilacoom, and none of the First Washington Volunteer Infantry ever got farther east than Idaho, saw a Confederate soldier, or fired a shot in anger.

Conscription

The difficulties that the Union cause had recruiting volunteers finally led to the passage of the Conscription Act in March 1863, the nation's first such coercive call-up of troops. All able-bodied males between 20 and 45 years of age were required to enlist in the army for three years, although exemptions could be purchased for $300 and substitutes hired to serve in place of those not willing. In Washington Territory, this at first proved even less popular than Steinberger's earlier efforts to muster volunteers. As one historian recounts:

"The enrolling officers appointed under the conscription act in 1863, to make up the lists of able-bodied men subject to military duty, met with some trouble, as they did everywhere else. The provost marshal established his headquarters at Vancouver, and special deputies were appointed in all the counties. Edwin Eells, who served in Walla Walla County, probably met with as much resistance in the discharge of his duty as any of them. The lawless element, which had been attracted to that part of the territory by the successive gold discoveries, was still strong in the community, and it was not patriotic in any sense. It became openly defiant when it began to be known that it would be compelled to furnish its share of recruits for the army in case of need. In one saloon a bucket of water was thrown over the enrolling officer; in another a bunch of firecrackers was set off under his chair, as soon as he began to write, and in another all his books and papers were taken away and destroyed" (Snowden, Vol. 4, 112).

Slowly, however, sympathy for the Union cause grew in Washington Territory, although it did not ever lead to mass enlistments. There was much else to be done, building new lives in a new land. Many men were loathe to leave their homesteads unguarded against attacks by Indians, which, although rare by then, did still occur. The war was being fought on battlefields far away; the only Confederate threat to the territory was the odd privateer roaming ineffectually in the waters of the North Pacific. There was simply little sense of urgency or peril this far west, and no great patriotic fervor.

Through the entire four years of war the regular Union Army found no Confederates to fight in the Northwest. In January 1863 it fought its only battle in Washington Territory, in the far southeast corner of what is now Idaho. Known as the Battle of Bear River or the Massacre at Boa Ogoi, the enemy was not the Confederate army, but Shoshone Indians.

War's End

Although there were scattered engagements shortly afterwards, the Civil War is generally considered to have ended on April 9, 1865, when Confederate General Robert E. Lee (1807-1870) surrendered to General Ulysses S. Grant (1822-1885) on the courthouse steps in Appomattox, Virginia. It was almost exactly four years since Southern forces had shelled Fort Sumter. During that four years more than a million American soldiers, North and South, had been killed or wounded.

The 1860 federal census had counted 3,950,528 slaves in the United States. At the end of the Civil War there were none, and a shameful, dark, and protracted chapter of American history was at an end. The secessions that had torn the country in two were rolled back, and the United States was again made whole.

Abraham Lincoln did not live to enjoy the benefits of peace; six days after Lee's surrender, John Wilkes Booth (1838-1865) assassinated the president, a tragic coda to a tragic era in the nation's history. Lincoln was succeeded by his vice-president, Andrew Johnson (1808-1875), and a long process of rebuilding and reconciliation began. In 1869, Ulysses S. Grant, the general credited for the victory of the Union forces, was elected to the presidency.

The Legacy of War

Washington Territory's distance from the battlefields and the reluctance of its men to leap en masse into the cauldron of a far-away conflict left its population almost totally unscathed by the most deadly war in American history. When the grisly accounting of dead and wounded was done, it could be seen just how moderate Washington Territory's contributions had been.

The total number of men from Washington Territory who volunteered or were conscripted into the First Washington Volunteer Infantry is uncertain, with different sources providing counts ranging from 964 to 1,521. Whatever the number, it represented a vanishingly small percentage of the more than 2,000,000 men who served the Union cause. Casualties were equally modest, and not a single member of the unit died in battle. The fatalities that did occur were:

- Twelve territorial soldiers who died of disease.

- Five who died from "accidents."

- Five more who died from "from all Causes except Battle," which included one murder.

("Union - Troops Furnished and Deaths").

There were no doubt other casualties with connections to the territory, including members of the regular military and men who had moved on their own to enlist in the East. One such was Isaac Stevens, killed at Chantilly. A few volunteers and military men from Washington Territory fought for the Confederate cause, but their numbers and fates appear to be largely unrecorded.

Fifteen men who were awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor during the Civil War are today buried in Washington state, all but one of whom moved here after the war ended. A sixteenth recipient, Hazard Stevens (1842-1918), son of Isaac Stevens, is buried at Newport, Rhode Island.

The memory of the war lived on in Washington Territory, and then in Washington state, in greater measure than the actual contributions made by its citizens. In Seattle, Stevens Post No. 1 of the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR) was established in 1878, the largest of nearly 100 such posts in the Washington Territory organized by veterans of the Union side. It began the tradition of an annual Memorial Day observance in Seattle the following year. In 1895, David (1833-1912) and Hulda (1829-1906) Kauffman donated land on Seattle's Capitol Hill adjacent to Lake View Cemetery to local chapters of the GAR for the establishment of a burial ground for Union veterans. The site fell into disrepair over the years, but between 1997 and 2002 it was rehabilitated by a volunteer group, Friends of GAR, and is still in use today (2013).

A Washington chapter of the Sons of Confederate Veterans was established in 1904 and still exists today. The Robert E. Lee Chapter No. 885 of the United Daughters of the Confederacy was started in Seattle in 1905 for the stated purpose of providing "care to the Confederate Veterans and their families" ("History," UDC website). In 1926, the group erected a monument in Lake View Cemetery in memory of "United Confederate Veterans." Although later vandalized of its bronze decorations, it remains there today, and the United Daughters of the Confederacy is still an active organization.

Washington Territory, far removed from the bloody battles and the keeping of slaves, suffered almost no loss of life or property in the war, but the issues that fueled the conflict, and their resolution, touched every corner of the nation. The blight of slavery was lifted from the land, and the Union that the territory hoped eventually to join, and did finally join in 1889, was preserved. The Civil War was a tragic ordeal for the country, but when it was over, Washington Territory had lost very little and gained much.