This piece on violence in the history of Seattle was written by Walt Crowley (1947-2007), Executive Director of www.historylink.org. It appeared in The Seattle Times on December 12, 1999, immediately following the massive protests in Seattle of the World Trade Organization's (WTO's) third Minesterial Conference, which took place in Seattle from November 29 to December 4, 1999.

A Brief History of Civil Violence in Seattle

Bands of radicals smash store windows and set trash cans afire. Teenagers loot stores. Police fire tear gas and swing billy clubs. Bystanders and reporters are injured or arrested. A business district is left in shambles. The policies of a liberal mayor are tested, and an embattled police chief resigns.

Downtown Seattle during WTO?

No, Seattle's University District in 1969.

As citizens and officials begin to investigate what went wrong during the World Trade Organization conference, they should remember that we have seen this movie before. Indeed, the events during WTO pale in comparison to some previous incidents of civil turmoil. We've experienced worse, and not all that long ago.

Like most Western cities, Seattle was forged in violence. The first "Battle of Seattle" was fought by settlers and Salish warriors, who attacked the village and were repelled by naval artillery and Marines in January 26, 1856. The public peace was later disturbed by lynchings, gun fights, and the ignominious Anti-Chinese Riots of February 1886, when an armed mob led by the Knights of Labor expelled the town's Chinese immigrant workers.

Unionization of the region's industries also produced its share of violence on both sides of the class divide. Five members of the radical Industrial Workers of the World died during a bloody gun battle in Everett in 1916, and another Wobbly was castrated and lynched after a 1919 confrontation in which four American Legionnaires died while storming the IWW office in Centralia.

Local labor's power peaked in February 1919 with the nation's first general strike, but this event was notably peaceful despite hysterical comparisons with the Bolshevik Revolution. Business in Seattle was effectively stilled for nearly a week, until most citizens grew weary of the inconvenience. The strike proved a Pyrrhic victory by undermining labor's public support and rationalizing government crackdowns on union militants.

The Great Depression helped restore organized labor's influence, but often at a high price. Longshoremen, teamsters, and sailors fought running battles with police, Pinkertons, and, sometimes, themselves, during the West Coast waterfront strike of 1934. Seven strikers died on the Coast that summer, including a Seattle longshoreman shot by guards in Everett. A Seattle "special deputy" also died during a clash with strikers near the Smith Tower.

Seattle Police armed themselves with Tommy Guns and gas grenades to defend Piers 90 and 91, while strikers lay down on train tracks to idle the docks. Mayor Charles Smith prodded Chief of Police George Howard to be more forceful, and Howard finally resigned rather than trigger a blood bath. The mayor took over and began arresting scores of suspected "Communists," but not enough to secure his re-election that fall.

The 1934 waterfront strike ended with a union victory and spurred passage of federal laws ensuring workers' right to organize and bargain collectively. Further reforms and the production demands of World War II helped to pacify labor-management relations in most industries.

Labor strife was not the only cause of civil unrest in Seattle. The large influx of African American workers and military personnel during World War II dramatically changed the complexion of the nearly all-white city. Ironically, many new arrivals occupied homes involuntarily vacated by Seattle's former Japanese American community, and the city's new citizens found themselves largely confined to a de facto Central Area ghetto.

Racial tensions briefly flared in 1944, when African American guards at Fort Lawton's POW camp rioted over their conditions, but black-white resentments mostly simmered through the 1950s. The pot didn't boil over until the late 1960s, although racial violence in Seattle was relatively mild compared to a Watts or Detroit.

Agitation against the war in Vietnam produced its share of violence on the local home front. The University of Washington campus witnessed arson fires, bombings, and even a "Battle of the Bees." Under late President Charles Odegaard, the campus fared better than most, chiefly by barring city police from University property.

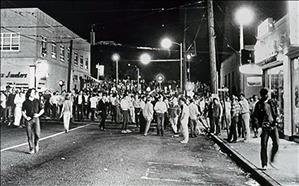

The generation gap, not politics, led to the worst nights of violence in 1969. They began when police broke up an Alki Beach concert with tear gas on August 10. The following night, "street people" battled police in the University District, and thousands of teenagers converged on "the Ave" for two more nights of rioting and looting. The disturbance was finally quelled when police retreated and let citizen volunteers patrol the neighborhood. Police Chief Frank Ramon, already undercut by a growing payoff scandal, resigned soon after.

Anti-war demonstrations moved to downtown Seattle in 1970, beginning with a riotous February demonstration at the Federal Courthouse that led to Chicago-style indictments against the "Seattle Seven." More violence followed the famous Freeway March of May 5, 1970, and simultaneous student strike at the UW.

After a May 7 evening demonstration in the University District, roving gangs of disguised "vigilante" Seattle Police officers attacked students and bystanders, while their uniformed colleagues stormed through UW dormitories. The next day, Mayor Wes Uhlman authorized a legal Freeway March on the Express Lanes -- escorted by police with daffodils taped to their truncheons.

Civil disturbances have been rare in the past two decades, but incidents such as youth-police clashes on Capitol Hill and the Rodney King post-verdict rampage should have reminded us that our city retains a capacity for urban violence. It is like a recessive gene that, while usually hidden and often forgotten, can flare up at any time.

Seattle's vaunted sense of its own civility took the worst beating of all during WTO. History does not justify last week's violence but it does show how such civic conceit can turn into a fatal delusion