On December 22, 1933, amid growing fears over the perceived threat posed by that relatively new fad, jazz music, Washington State Representative William A. Allen submits his proposal (House Bill 194) to establish a commission that will study the presumably dangerous and deleterious effects that the largely African American art form might be having on the general public. Allen's bill never comes to a vote, but it exemplifies a long tradition, which will be repeated a generation later for rock 'n' roll, of efforts by authorities to clamp down on new trends in music.

Fear of Music

In countless instances over the centuries, new forms of music have been forbidden by rulers, religious leaders, and other societal and governmental authorities all across the globe -- often because music is seen as a potentially destabilizing force. These authorities' various angles of attack have included condemning songs for their beats, tempo, chord structures, instrumentation, volume, associated dance moves, or what they consider offensive lyrical content.

This fear of music is, however, not completely without merit as songs can have the ability to convey new ideas; to explore shockingly innovative chordal, melodic, and rhythmic terrain; to introduce radical instruments and their sounds; and to inspire new sensual body movements by dancers. The historical record reveals that most attempts to formally ban such things have failed. But not all -- and when jazz music arose about a century ago (as with rock 'n' roll music, five decades later), its detractors were legion.

As a matter of fact, plenty of people saw a direct correlation between jazz and rock 'n' roll -- and in truth, those two realms do share some musical DNA. But the people who fretted about such things also often shared a certain mindset about racial matters. For example, London, England's Daily Mail editorialized in 1956 that rock 'n' roll "is sexy music. It has something of the African tom tom and voodoo dance [about it]. It is deplorable. It is tribal. And it is from America. It follows rag-time, dixie, jazz, hot cha cha and boogie woogie, which surely originated in the jungle. We sometimes wonder whether it is the negro's revenge" (Blecha, 1, 15).

As an energetic and particularly rhythmic new form of music, early jazz faced detractors all across America -- opponents who had a propensity to couch their concerns in quasi-medical terms. In 1912 one elitist, writing in Musical America, claimed of jazz fans that "ragtime has dulled their taste for pure music just as intoxicants dull a drunkard's taste for pure water" (Berlin).

Jazz Menaces the Northwest

As a backdrop to the saga of the rise of jazz in the Pacific Northwest, it is not an insignificant factor that, for much of the twentieth century, Seattle had two racially segregated musicians' unions, the American Federation of Musicians Local 76 (for white players) and the "Negro Musicians' Union" AFM Local 493 (for everyone else). The fact that little Local 493 boasted the vast majority of the Northwest's jazz players is not irrelevant to understanding why some Seattleites -- including preachers, politicians, police, and newspaper publishers -- would have such a profound disdain for the music and its makers.

The "first documented jazz performance by a local band in Washington took place on June 10, 1918, at Seattle, Washington's Washington Hall [14th Avenue and Fir Street]. The performers were Miss Lillian Smith's Jazz Band" -- presumably an African American ensemble (de Barros). And the backlash against this music was soon to come. As early as June 13, 1921, The Seattle Daily Times published a front-page item with this headline: "Is Jazz Menace to Civilization? Worse Than Booze, Say Club Women." The essay went on to note that jazz "is a menace as serious as the narcotic menace and even worse than liquor." Indeed, one of the social club's leaders -- the music chairman of the General Federation of Women's Clubs -- stated that "as dearly as she loved music, she would rather see it wiped out of existence than to have it succumb to jazz."

And thus we see another early example of music falsely equated with chemical addictions. It was that same year when the Reverend Mark Matthews (1867-1940) of Seattle's First Presbyterian Church famously fulminated that "jazz is an evidence of intellectual and moral degradation" -- while a doctor in New York issued a report asserting that jazz "intoxicates like whisky" and "releases strong animal passions" (Blecha, 22).

Action in Olympia

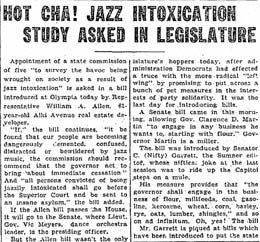

It is interesting that although Washington's 17-year-long experiment with alcohol Prohibition (1916-1933) was ended with federal repeal in 1933, the crusade against jazz didn't stop. In fact, it was that very same year that West Seattle's (District 34) State Representative William A. Allen whipped himself into frenzy over the perils of the music -- music that was by now wowing crowds nightly in any number of black-oriented speakeasies and nightclubs strung all along Seattle's S. Jackson Street scene. On December 22, 1933, Representative Allen -- a freshly elected real estate developer who was originally from Georgia -- submitted his "Jazz Intoxication" measure (House Bill 194) to the Washington State Legislature at the State Capitol Building in Olympia. This move was deemed newsworthy enough to merit front-page coverage in The Seattle Daily Times.

Allen's intention, as stated in that bill, was to establish a five-man statewide commission "to survey the havoc being wrought on society as a result of jazz intoxication." Furthermore, "If it be found that our people are becoming dangerously demented, confused, distracted or bewildered by jazz music, the commission should recommend that the governor act to bring about immediate cessation." Fret not though, Allen had a solution in mind for this problem: "All persons convicted of being jazzily intoxicated shall go before the Superior Court and be sent to an insane asylum" (The Seattle Daily Times, 1).

Alas, we will never know how that year's legislature would have voted on HB 194, as it never made its way to the floor of the House for a vote. Still, The Seattle Daily Times could not resist noting, with a bit of humor, that if HB 194 had passed the House it would then have gone "to the Senate, where Lieut. Gov. Vic Meyers [1897-1991], dance orchestra leader, is the presiding officer." Indeed, Meyers had plenty of personal experience playing wild dance music for liquored-up crowds who thronged an illicit speakeasy in Seattle's Butler Hotel all through the Roaring Twenties. Still, despite the threat posed by HB 194, jazz fans will likely rest a bit easier knowing that Representative Allen served only one term and was out of office by 1935.