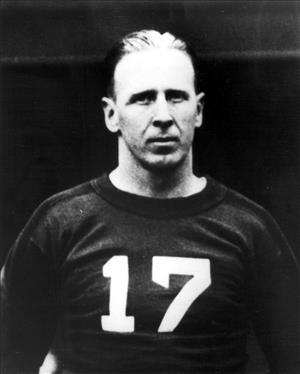

On December 17, 1933, Red Badgro (1902-1998) scores the first touchdown in the first official National Football League (NFL) championship game. Badgro, who grew up near the small town of Orillia in South King County, is an end for the New York Giants, who are playing the Chicago Bears for the championship. A multi-sport athlete who has also played major-league baseball, Badgro will go on to complete a nine-year NFL career and in 1981 will be inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

Three-sport Star

Badgro grew up on a farm near Orillia, a one-time community in southern Tukwila, and was a standout baseball, basketball, and football player at Kent High School and the University of Southern California (USC). He played major league baseball briefly with the St. Louis Browns before making his mark in the National Football League.

The NFL was formed in 1922 but did not have an official championship game until 1933 when it was split into two five-team divisions. By then Badgro was in his fourth season with the Giants and twice had been named an All-Pro. He played both offense and defense, and was known as a rugged blocker and tough defender. He also was one of the league's top receivers, although runs were more common than passes in those days.

Making History

The 1933 Giants were coached by a defensive lineman, Steve Owen (1898-1964), and had two other future Hall of Famers with Washington ties -- center Mel Hein (1909-1992), who played at Washington State College, and end Ray Flaherty (1903-1994), who grew up in Spokane and played at Washington State and Gonzaga. After four victories in their first seven games, the Giants won their remaining seven while allowing just 33 points, winning the Eastern Division title. That set up a showdown with the Western Division champs, the Chicago Bears, who had a defense even better than New York's and three men on their way to legendary status -- coach George Halas (1895-1983), halfback Red Grange (1903-1991), and fullback Bronko Nagurski (1908-1990).

The championship game was played at Chicago's Wrigley Field before a crowd of about 30,000. The Bears made two field goals to take a 6-0 lead before Badgro made NFL history. In the second quarter, he caught a pass from rookie quarterback Harry Newman (1909-2000) for a 29-yard touchdown and a 7-6 lead for the Giants. Although it was the first title game's first touchdown, it was greatly overshadowed by the drama that followed.

The Giants were ahead 14-9 in the third quarter when the Bears turned to brute force, giving the ball to Nagurski on nine straight plays to the Giants 16-yard line. The next play started out looking like another run by the powerful fullback, but he pulled up before crossing the line of scrimmage and threw a jump pass to Bill Karr (1911-1979) in the end zone. That touchdown plus the extra point put the Bears on top, 16-14, setting up a fourth quarter for the ages.

"Wild Finish"

"Only a Hollywood scriptwriter could have conceived the wild finish," Joe Garner and Bob Costas wrote in their 2011 book, 100 Yards of Glory (64). It started with Newman completing two straight passes to Flaherty for a total of 51 yards, and Giants halfback Ken Strong (1906-1979) running for another 15. At that point, the Chicago defense stiffened, forcing the Giants to improvise a play that came to be known as a flea-flicker. Newman took the center snap and handed the ball to Strong. He tried to run around left end but was hemmed in by Bears. He lateraled the ball back to Newman, and the quarterback started running to the right. With defenders converging on him, he stopped just short of the line of scrimmage and threw a touchdown pass to Strong waiting in the end zone. The extra point put the Giants ahead, 21-16.

The Bears again turned to Nagurski, and he again surprised the Giants by passing. From the New York 33, he threw to Bill Hewitt (1909-1947), an end playing without a helmet. (Although worn by nearly all players, helmets were not mandatory.) Hewitt lateraled the ball to Karr at about the New York 19 and Karr took it in from there, giving the Bears a 23-21 lead with about three minutes remaining.

One more remarkable play remained. It would be the game's last, and it would involve Badgro. He caught a pass from Newman and was headed for the goal line with a teammate -- he thought it was Hein or running back Dale Burnett -- close behind him and only Grange between them and the end zone. Badgro intended to pitch the ball back to his teammate and block Grange out of the play, but Grange lunged and grabbed him around the upper body, pinning his arms to his sides so he couldn't get rid of the ball. They went down in a heap, the ball sandwiched between them, just short of the goal line. Chicago won the championship, and Badgro and his teammates had to settle for the loser's share, $142.22 each.

Unforgettable

The Associated Press account of the game called it "a thrilling combat of forward passing skill, desperate line plunging and gridiron strategy that kept the chilled spectators on their feet in constant excitement" ("Bears Beat Giants"). Writer Peter King in 1995 rated it the greatest game in league history.

It was one Badgro couldn't forget -- not for his touchdown but for the one he was denied.

He was living in retirement with his wife Dorothea at their home in Kent when he was voted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1981 at age 78. It had been 45 years since he quit playing, and 48 years since that first championship game. When interviewers asked him about it, he invariably brought up regrets about the final play. "I wish," he said, "I had the ball again" (Litsky).