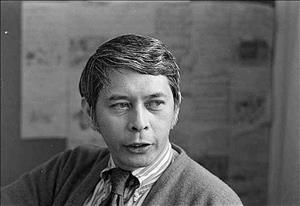

Bob Santos (1934-2016), born and raised in Seattle's Chinatown-International District, spent most of his life as an activist in his old neighborhood -- saving it, nurturing it, defending it against outside threats, whether environmental, cultural, or political. Considered the unofficial mayor of the ID and known to most as Uncle Bob, he was arrested six times fighting for civil rights. On July 30, 2014, he sat down for an interview with HistoryLink.org intern Alex Cail and that interview is here presented in four parts. In Part 3, Santos talks about his work during the Clinton years as director of the Department of Housing and Urban Development's Region 10; providing shelter for the homeless in Seattle's old Federal Building; keeping a planned prison out of the International District; and efforts to create a community that welcomes and attracts residents from a range of socio-economic backgrounds. The interviewer's questions are not included, and the transcript has been slightly edited for clarity and length.

Influence and Innovation

I ran for office a couple times. I didn't win. So I said "that's not for me," but I was appointed the regional administrator for the Department of Housing and Urban Development. The United States is divided into 10 regions. The East, New York, that's Northeast section, and you have the Southeast section, and the Midwest. Ten different zones actually, and up north, here, the Region 10 states are Washington, Oregon, Idaho, and Alaska. I was appointed to run the HUD office in the region. So that was pretty good. An elevation to a really high position, because as regional director of HUD, we're representing the administration, the White House, in all matters that deal with housing issues.

I did that for two terms under Clinton. I'm sitting here in this big plushy office, and everything is done for you. When you're working in a community, your mind is consistently trying to figure out how to get resources to run your programs. When you're at HUD, you are the resource. You're the ones that start throwing money out there to the communities. I wasn't used to that kind of stuff -- it was a nice change.

I'm sitting there and thinking "God, there's gotta be more to this," and then I figured one day, "I'm never going be in this influential position ever again." I come from the community, and all of a sudden I'm representing the administration in this whole region. So I started to do stuff that the HUD office had never done before. One of the key things I did was open up the Federal Building as a homeless shelter. And that's never been done before -- not in a federal office. And I worked with other federal agencies in the building, the old Federal Building, got them to a meeting and said "This is what I want to do, I want to bring in the homeless folks here, because this building has lights, it has heat, it has showers, it has bathrooms. And there's no one is in this building after 8 o'clock at night until 6, 6:30 in the morning, it's empty, so let's use it."

There was a lot of apprehension too, because some of these directors of other federal programs didn't want these homeless people running around the office. I promised them that we would find an area that could be secured, that they wouldn't have to worry about people running around the building, and then we would hire security just for that period of time the homeless people were here. And they bought that, they said, "Okay, let's try it out for six months, let's meet again, see, and then you tell us the results." After six months I called them back, and they said, "Well, when do we start?" I say "They've been here for six months, but you've never seen them, none of your employees have ever seen the homeless people" because they leave at 6 o'clock in the evening, the homeless people come in at 8 p.m., and there's never overlap.

So, when I'm sitting here in Seattle, thinking about projects to do ... I'm thinking, "I'll never be in this position again, to really do something for the community." And my bosses are 3,000 miles away in Washington, D.C. They don't care what I do out here as long as it's still legal. My boss, President Clinton, I mean, he's got his problems with Monica Lewinsky. And the secretary, my boss, Henry Cisneros, he has some women problems out there. They don't know what I do out here.

So I used that, I said "I'm gonna start doing things outside the box," and it was always accepted by my bosses in D.C.: "Santos, if you can run this program successfully, you go ahead with it." [It gave me more freedom] than any other regional guy, because every other regional guy, they operated under that strict cylinder, they never went outside that cylinder. I said "Bullshit." You come from a community, you really gotta be innovative. There's no reason why government can't be too.

Protecting the Community

Before I got into the government [I dealt with issues] such as the plans for a work-release center and prisons. Because people are always thinking of placing "unwanted projects" downtown that were unwanted by other neighborhoods. "Well, let's put it in the International District, because those folks down there, they're not gonna mind." Well, we said "No." [It wasn't racial so much] as availability of land that was probably more affordable in the downtown area. International District property values were a little bit lower.

There were work-release programs that were planned. An actual prison was being planned by the federal government on 8th and Charles Street, just right on the other side of Dearborn. And at the very same time that the government wanted to build a prison I was working for the Public Development Authorities, and I helped acquire the property that the village square was on, two half-blocks there that we developed. But as we were planning development there, the feds wanted to build a prison. We said, "That's not going to help us with funding sources." Foundations, businesses, even government, are not going to invest in our community if there's a prison across the street. So we stopped that. They built it up by the airport.

It took a lot. We had to go to the senators, all the politicians. And you go to the elected officials because they're the ones that hate bad publicity. In our minds we just terrorized the elected officials. McDonald's wanted to open up a franchise here, right on 5th and Jackson -- we stopped that. The reason why is if we would allow the first national franchise in our community, all the others would follow, so we had to stop the first one, so we stopped McDonald's. It's not forever. McDonald's is still the primary financial support of the International District street fair, the Dragon Festival. They're sponsoring that as the biggest sponsor, so they're hovering. But at some point they're going to try to open up again down here. If we're smart enough we'll just keep them at bay.

The city and the county were coming up with the idea of building an "energy recovery plant" just south of the district. Energy recovery is garbage burning. And they were going to bring in 20 tons of garbage and trash a day and burn it. And of course, you know, the fumes and the ash from that garbage burning plant would settle here in the International District, because the winds come from the southwest every day. So we stopped that even before it went to a planning grant. They wanted our support to apply for a federal planning grant, the city and the county were together on that. We met with them and said, "No way, we will not support this." And they actually listened to us and they shelved that project. They're telling us, "Well, it works in Europe," but this isn't Europe, this is our community. And none of those folks live down here.

Changing Minds

When you're looking back, you're comparing, I'm comparing our community here with other communities around, especially in the urban center in the downtown area. Most communities want a vibrant resident base. Most communities want people living in their communities with higher incomes. So they can shop, and go to their restaurants, and all that kind of stuff. Here, we want a strong resident base, but we're willing to provide housing for the lowest incomes, all the way up.

Most people don't want low-income people in their neighborhoods. I mean, if they were there when they got there, that's okay, but they're going to die off -- right? So, most communities want to build a very strong residential base with middle-income people and above. Here, we've gotten the community to understand that, no matter how much your residents earn, they're going to spend 95 percent of the income in your community. To get everybody in the community agreeing that providing housing and services -- healthcare and all that -- for retired seniors and low-income families is a good thing, is a positive thing.

To go to Part 4, click "Next Feature"