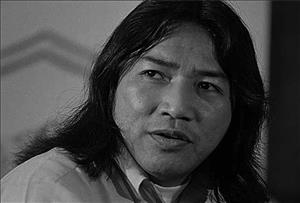

Bob Santos (1934-2016), born and raised in Seattle's Chinatown-International District, spent most of his life as an activist in his old neighborhood -- saving it, nurturing it, defending it against outside threats, whether environmental, cultural, or political. Considered the unofficial mayor of the ID and known to most as Uncle Bob, he was arrested six times fighting for civil rights. On July 30, 2014, he sat down for an interview with HistoryLink.org intern Alex Cail and that interview is here presented in four parts. In Part 4, Santos tells the story of the "Gang of Four," a group of activists representing four different ethnic groups; summarizes some of their accomplishments; reveals plans for a book about the group; and muses with some regret about the effect his activism has had on his family life, and what he would do differently next time. The interviewer's questions are not included, and the transcript has been slightly edited for clarity and length.

The Gang of Four

I'm also writing a book now, just completing, with another guy, we're co-authoring a book called A Gang of Four. One Mexican guy, one Native American guy, one black guy, and me, the Asian guy. We formed a coalition. We were, all four of us, executive directors of our own agencies, serving our individual communities. And at one point, we got together, said "Hey, we have to work together." So it was really a very innovative approach for activism that included all the major ethnic groups. [It was me], Bernie Whitebear, Larry Gossett, and Roberto Maestas. Maestas and Whitebear both passed away. After they passed away, Larry Gossett and I said, "We gotta write this book, we gotta, before anybody else leaves." So we have our own publisher.

Each of us was directing our own agencies, and this is when the four of us were hired by our community groups in the late '60s into the '70s. And Bernie Whitebear organized all the Indians in the region, and they occupied Fort Lawton. The land at the fort was being surplused by the government back to the original owners. And the city said "We're the original owners," and the Indians said "Bullshit! We're the original owners." And so the Indians went over the fence, climbed over the fence, and they set up teepees and occupied the fort for several weeks. So that was Bernie Whitebear leading that occupation.

Roberto Maestas and the Latinos saw this old abandoned school on Beacon Hill. So the Latinos occupied that school, Beacon Hill School, and through the years were able to acquire that building and the land to build El Centro de la Raza, which is a service area to the community, Latinos and others.

Larry Gossett was executive director of the Central Area Motivation Program. One of the first anti-poverty programs that were funded through the federal government in the late 60s. And so that organization provided all kinds of services to the black community, especially in the central area.

And I was down here at the International District, preserving neighborhoods, building housing.

When we got together as the Gang of Four, here you have these activists, militants, that were leading demonstrations, and getting arrested. All four of us were in that. But then, on the more relaxing side, we were goofy. And when we were with each other, we just nitpicked, and we just teased each other, and people wouldn't understand it. I can't write about our relationship in the book that I'm writing, because people wouldn't believe it. And some of 'em would say, "That's sort of derogatory, you know, some of the things you did." Well, it's just like a group of friends, guys, it was guy things, hate to say that, but it was guy mentality. And there's hundreds and hundreds of stories about the lighter side of organizing communities. Yeah. Anyway.

So, each of us had our own projects that we were dealing with, but then we joined forces many times to support each other's causes. And that was something that was pretty unique. You look in any urban neighborhood throughout the country, you don't find that. So that's why we're writing this book. And we think -- our publisher thinks -- that it's going to be a very popular book in the urban centers throughout the country. So, we'll give it a shot. And the Muckleshoot Tribal Council voted to finance the whole project. We don't have to raise any money, so that's pretty cool.

Hard on the Home Front

The family actually suffered when they're growing up and Dad's out organizing the community 'til nine, ten o'clock every night, and one of the things I found out very early on down here, when you organize a community like ours, it's hard for me as a director to go to the business community and say "Listen, I'm director of a program, we're here to help you." And you know what they would say, the businesses? "Not right now, Bob. This is a mom-and-pop operation. Just me and my wife are operating the business. We don't have any time to talk to you. We're trying to survive." And so, I'm thinking, "How do I get to these people?" You sort of have to make time with the people who you want to interview. It's easy to do interviews from nine to five, that's where most people do their interviews, and people working in administrative positions -- I'm talking probably mostly in business -- they don't like to work overtime, not when they don't get paid for it.

In non-profits we don't get paid for overtime, but you have to find out the best way to get to people that you want to interview. If it's after work at a bar, that's where you have to go. They're relaxed. They're relaxed and they complain about everything that's going on, and all you do is just listen and store it in your mind about what their issues are, without even asking: "What is your problem down here in your community?" They're not going to tell you. But if they're among each other and you're a bystander, they don't mind talking about what their issues are.

Some of them are saying, "I hate those activists, those communists." So we had to think about "How do we get them to accept what the activists are doing?" And, you know, the garden, creating and building that garden, where the activists were out there. Before then they were out there marching, cussing, and swearing, and having a good time on demonstrations, the business community said "We don't like that kind of attention down here." But when they saw the same activists up there in the garden, knee deep in horse manure, and creating this garden, they're saying "look, they're for real." They started realizing how important our existence was in their community.

In the early days, we were raising a family -- Anita [my first wife] and I -- were raising a family, and I'm spending as much time on the job as I am at home, and there were some instances where people were arrested. And one person that was arrested was an immigrant, and we had to come up with bail to get him out of jail. So, I put my house up for bail. And when I told my wife that, she said "You can't do that kind of stuff, jeopardize our whole family, losing our home for some guy that" -- she said -- "I don't even know."

I started doing things like that, and when you look back on it, I was pretty rough on family life. I still took kids to Saturdays, their football games, and basketball games, and if I got home early enough I'd always cook, so I did a lot of that. But she had to raise the family. She was working at that time, at Boeing, and I just put too much pressure on her to spend all her time -- free time -- with the family. And I learned a lot from that -- you know. You gotta be home.

Now, with my wife, Sharon Tomiko, I do all the cooking. I do all the laundry. I do all the dishes. So that way, well, my wife is a state legislator. So she's out at meetings, and the meeting ends at seven o'clock. I don't want her rushing to the store, shopping and cooking a meal that she slaps together -- right? So I said, "Hey, listen. You go to your meetings, and don't worry about rushing home to cook a meal. The meal will be ready when you hit that door, when you come in." So it's a shared responsibility that we have.

If I'd have known that very early on, I might have been together with my first wife -- no, she passed away, but -- you know. It's a different environment when you're growing up as an activist. You're only thinking of yourself and the community that you're trying to make friends with. And then, the second thought is your family. That was all backwards. If I did that today, it would be family first, and then [the general community].

Today I'm still involved in leading tours down here [in the International District]. I provide lectures, just like we're talking about, the activism and preservation of the district. A lot of young people want to learn about the civil rights movement, the human rights movement, and I provide, from my point of view, my involvement in those issues. So I'm still doing that.