Maltby and Neighbors, a book issued by Snohomish Publishing Company in 2012, relates the early history of previously undocumented areas in South-Central Snohomish County including the small communities of Maltby, Grace, Cathcart, Clearview, and Lake Beecher, as well as settlements at Paradise Lake, Crystal Lake, Echo Lake, and Lost Lake. Geographically this area lies south of the town of Snohomish and is bounded by the Snohomish-King County line on the south, the Snohomish and Snoqualmie rivers on the east, Little Bear Creek on the west, and Fiddler’s Bluff-Lowell Road on the north. The book's author, local historian Elsie L. Mann, originally set out to write the history of Maltby's First Congregational Church, but her research in early newspapers, land and logging records, city directories, maps, documents, and oral histories turned up more than she used in the church history. What she found became the substance for her book Maltby and Neighbors. The People's History presented here by Elsie Mann is an abridged version of the book

Rails for Logs

A large area in South Central Snohomish County remained sparsely populated after the county was formed in 1861. There were desirable stands of timber, but logging occurred only in places where logs could be put into a river. That changed in April 1887 when construction of a railroad began. The West Coast Railway, a branch of the Seattle, Lake Shore & Eastern, was built through the area from Squak Slough (Woodinville) to Mission, British Columbia, for connection with the Canadian Pacific Railway.

Railroad contractor Thomas Earle & Company established a work camp known as Earl. This was located near a steep grade down to the river valley. It was so steep that trains had to be broken into small sections and moved down or up to "The Summit." From the other direction, trains had a long gradual grade to climb that was later called "Maltby Hill." To ascend the hill, trains had to be small and often needed a pusher engine to get them up to "The Summit."

Early Settlements

Logger Judson Lee was the first land claimant near "The Summit." He was followed by several investors and a pioneer, Ole Helickson Lee, who labored to build a community. The post office was Ole's dresser drawer after he established the future town as Yew (later Maltby). He successfully petitioned for and helped create county roads, a school district, and a voter precinct. George Stevens opened a store after his arrival in 1890 and installed telephone and telegraph service at the depot. The following year the town of Yew was platted.

Some two miles away, a group of Welsh settlers claimed property around a small lake they named Paradise. They called their settlement Paradise Valley. Many of the claimants sold their timberland to the Port Blakely Mill Company. Those who stayed were coal miner James Morgan Lloyd, whose farm was managed by his wife Eliza Ann, and farmers George Compton, William Daniels, and Henry Davis.

Thomas Sanders, John B. Kelly and Thomas Flaherty located near the Snohomish-King County line. The railroad established a flag stop there known as Grace. This was where locomotives began to strain to make it up Maltby Hill. Edgar Turner settled his parents and siblings farther away at a place that took the name of Turners Corner. He donated an acre of land for the Bear Creek Cemetery. Edgar and three siblings were teachers who educated children in the surrounding areas.

Midway down the steep grade from the summit was a stop named for logging camp owner Isaac Cathcart (1845-1909), an Irish immigrant. Cathcart willingly let the railroad go through his property. This was where trains were taken apart and put back together. Mr. Cathcart did not sell his logged land for settlement, so there were few settlers before 1913.

George H. Robinson and his brother-in-law Hans Robertson had located on a hilltop farther inland. They both moved down to Cathcart when their children were of school age. However, the children had a long treacherous walk down to the schoolhouse established at Lake Beecher in 1892. Lake Beecher was on the river delta, far below Cathcart Station. Mr. Cathcart owned a productive farm there. He and other logging companies used a long channel from the lake to get logs into the river.

The very first settler, John Krieschel, lived nearby. He too had an extremely productive farm because his wife, Ts-sal-ah-hass, aka Mary McYale, had many relatives working there. His farm was perilously close to the Snohomish River on a hummock that the annual floodwaters swirled around without disturbing his buildings or the people. Archeologists now believe this spot had once been a seasonal camp for the Native people. John had settled on it before Snohomish County was established. His wife and children stayed on Henderson Island until 1872.

A huge promontory loomed between Lake Beecher and Snohomish. This was blasted away by the railroad company to provide a roadbed. It was known as Fiddlers Bluff because a morose logger of questionable skill had settled atop and frequently sawed away on his fiddle.

A depot and sawmill were constructed at Yew (Maltby), while Grace and Cathcart were considered flag stops. Grace got a depot during its mill days, 1905-1911. There was no resident station agent but wooden benches lined the walls inside. The depot was removed when the county road was relocated to parallel the railroad track. Even later, probably after 1913, Cathcart had a covered waiting area and ticket office.

Fragile Beginnings

Development languished in most of the settlements due to the vagaries of the logging business. Robert Maltby purchased some land in 1890, subdivided it and went to Seattle to open his real-estate business. To accommodate him the post-office name was changed to Maltby in 1893. Albert V. Gray came to Maltby and built a schoolhouse in 1894, returning a year later to open a store. Within a short time, he also owned and operated the mill. Ole Lee built a shingle mill along a small tributary into Bear Creek.

Isaac Cathcart had gone into partnership with John Weber and built a large mill near Lake Beecher. This ended within six months and the mill was removed by creditors. A Canadian named William Blackman had a shingle mill on Fiddlers Bluff and Advance Shingle owned by Ford-Shaw was near Cathcart Station. It was moved to Maltby, then to Lake Beecher, and finally was sold at a sheriff’s sale.

In 1894, Isaac Cathcart built a large hotel at Cathcart Station. He began to experience cash-flow problems and made a contract with John Edgecomb, partner in the Winsor Mill in Bothell, to log a portion of his holding. He lived his final days in Seattle, and his sons shared ownership of the farm.

John Edgecomb initiated construction of a logging railroad to move logs to the Snohomish River, where the site was called a log dump. It was felt that one of the large mill companies was financing Edgecomb in this endeavor. By 1896, Cathcart was forced to put his holdings in the hands of a trustee. The timberland was taken over by Snohomish Logging, formed in 1900, and Snohomish Investment Company sold the logged land for homesteads.

Maltby, Paradise Valley, and Grace

Much of the area experienced prosperity right after the turn of the twentieth century. At Maltby, Hotel Stevens was built in 1902 and operated by Mary Stevens. Albert Gray built another store, and his father-in-law, Herbert H. Smith, took over the old one. Several new settlers arrived. Ole and Sena Lee donated a lot for construction of a Congregational Church designed by Albert Gray. It was completed early in 1905. The Maltby Bar was operated by Button & Dadow and another by Conrad Wiesel. George Olson’s bolt camp was operating and blacksmith Ben Kaiser was in residence. Postmaster Kellogg functioned in his own building and a Bruhn and Henry store opened nearby. Nils Johnson built a house across from the church for his growing family and moved there in 1907. The following year an eight-room parsonage was constructed on a lot next to the church. Another mill was built slightly north of Maltby at Diffley’s Spur. This mill changed hands frequently and closed within five years. Other 1902 arrivals were Thomas Fales, Jacob Mortenson and Joshua Dorley.

The settlers in Paradise Valley built a Congregational church in 1890. Six years later the church burned and the site was continued as a cemetery, since a small child had been buried there. By 1900, rail lines for logging purposes were built for a Shay engine. Logs were moved to landings by donkey engines. The Paradise Lake Shingle Mill was near the northeast end of the lake. School was held in the mill house from 1901-1903 when it burned down. A sawmill rumored to be funded by Port Blakely Mill was planned for the southwest end. This happened after completion of successful condemnation proceedings in 1902 for a railroad. This line connected with the one at Maltby. The saw mill and worker houses were built, but the mill failed and closed within three years.

At Grace, development was just getting under way. August Buthe and Thomas Flaherty had shingle mills on their properties. The Carsten Brothers, Henry and Allyn, operated Grace mill, a new shingle mill along Little Bear Creek. Woodinville Lumber owned by Jesse Brown & J. A. Rebhahn established a sawmill on adjacent property and had a logging camp and rail line, which ran alongside Little Bear Creek. There was also Fred Opdike’s shingle bolt camp. The Grace store opened on Woodinville Mill property and housed the Grace post office. The post office closed after two years in 1909 and the store went out of business the following year. Amid the prosperity, a new school house with two huge rooms was built. The children climbed over a stile to reach it. One room was used for classes, the other for rainy day recess, church, and social activities.

Brace, a logging spur from the railroad now operated by the Northern Pacific, was put in for Brace & Hergert, operators of the Western Mill in Seattle. Their line extended along Little Bear Creek for two or three miles. They transported logs and finished products from a mill on Thomas Ewing’s property next-door to Edgar Turner.

C. D. Hillman and Company

A 1907 downturn in the lumber industry put the Grace and Cathcart mills out of business; only the Maltby sawmill and Ole Lee’s shingle mill survived. Ole built a new house and large red barn covered with shakes from his mill. The settlers began experimenting with creation of productive orchards and berry fields and some began taking the train to jobs in the city. Granges were established at Maltby, Grace, and Cathcart, but these lasted only a few years. Snohomish Investment Company sold most of their holdings to Robert and Margaret Henry. This was 3,800 acres of Isaac Cathcart land that had been or was being logged. It was wrested from them through a 1908 lawsuit initiated by Clarence Dayton Hillman (1870-1935) doing business as C. D. Hillman’s Snohomish County Land and Railway Company, incorporated on August 6, 1908.

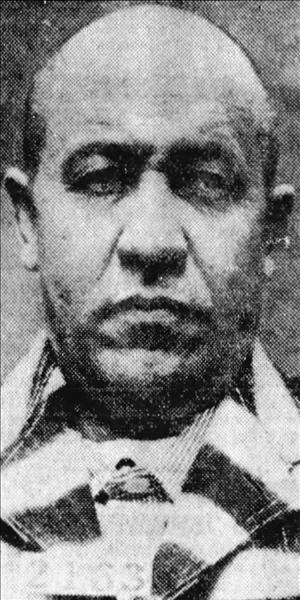

Isaac Cathcart's sons were often in financial difficulty. Isaac Jr. died in 1914 and William became heavily indebted to Clarence Hillman, who took over the ranch. Mr. Hillman had been convicted of fraud in a real-estate deal in Seattle in 1905. Again he was convicted of fraud in connection with land transactions in Snohomish County and was sentenced to jail. While on appeal, he announced establishment of a new office in Seattle and vowed to surround himself with only upright honest employees. By then, the estate had somehow doubled to 7,000 acres, of which 300 acres had already been sold, according to publicity. The estate was legally platted as Cathcart in October 1913 by Clarence Dayton Hillman and Bessie Olive Hillman.

The early proceedings were carried out by the Cathcart Development Company, because Mr. Hillman was in court again and sentenced to two years and nine months at McNeil Island for mail fraud in land transactions and contempt of court for trying to influence a judge. In 1916, he was found guilty of fraud in California and received a sentence. He was not with the family in 1920, when Bessie, the children, and a maid lived in an exclusive hotel in Paso Robles, California. He may have been finally serving time.

Hillman developments were attractive to folks wanting a fresh start or down on their luck. Only a small down payment was required for a small piece of land, purported to be able to support a family. Those without sufficient funds were hired to build houses or do some task for the developers. If a family wanted to depart, they could transfer their equity to another Hillman development.

The Hillman Company financed construction of houses, commercial buildings, and gas stations. These were sold to enterprising settlers. The houses were of wood construction, about 20 x 25 feet, and were built directly onto the ground. Settlers were hired to do the clearing, leveling, and construction. They were encouraged to raise rabbits, chickens, pigeons, berries, and produce on their small plots. Periodically, the company distributed free plants and vines to the homeowners. Mr. Hillman randomly came through with a group of potential investors and usually made a generous promise of some service or gift for the residents. Roads were being established, the Cathcart Hotel was again in operation, and a store and post office opened. Development took place on the hillsides and lower areas, because there was little access to the property atop the hills. In fact, it extended to Cherry Street in Maltby where a “Welcome to Cathcart” sign was erected above the county road.

Logging, Shingles, and Liquor

Snohomish Logging moved toward Maltby and in 1916 purchased a large amount of standing timber in the Maltby lakes area. The closest logging camp consolidated with a new one opened between Echo Lake and the Compton ranch at Paradise Valley. This new camp contained housing for families and added greatly to the area population.

Also in 1916, W. G. Goe operated the Graham Lake Shingle Mill for owner Alex Livingston who built a tramway from the railroad to the lake. A long freeze the first winter enabled bolt makers to put more shingle bolts on the lake than anyone could recall previously seeing. Herbert H. Bean took over the operation and finished after two years. A Seattle Sportsmen Club retained the lake and surrounding area for hunting and fishing.

Some area residents survived in part due to the sportsmen and because Prohibition went into effect at this time. Sportsmen flocked to rural areas and returned home with liquor from local stills, since many farmers had it for "their own use."

At Cathcart, C. D. Hillman sued his partners and gained control of everything. By then, people were living in tents and makeshift quarters while waiting for houses or trying to get one built. This touched the hearts of Snohomish citizens, who gathered bedding, clothing, and food to distribute to the needy.

Maltby Advances

Back at Maltby, things were advancing. A larger school was constructed in 1916 and locals were beginning to invest in poultry. Horticulturist Ben Hoggarth worked to develop plants suited to the climate and became a major local employer with his strawberry fields. He also developed a tomato, which he patented as "Beefsteak."

The Compton family had a large cherry orchard whose excess was sold to the Kirkland Cannery. Robertson Wellington Crim, Bill Suttles, and some of their neighbors had dairies. Fred Hall and Severin Sween both established large poultry and egg businesses, requiring many local employees. Victor F. Hugo and his wife, Fanny, operated two cars in a jitney business and opened a dance hall.

World War I and After

The community was moved to action because of war in Europe. They purchased government bonds and stamps during World War I, solicited and gave programs for the Red Cross, and sent funds so the boys "over there" could have "smokes" and make phone calls home. A teacher at Grace had her children making rifle wipers and writing letters to the soldiers. When the war ended, the boys were welcomed home and things got back to normal, most thinking this war had ended all wars.

On the home front, little attention was paid to the needs of the Snohomish Fruit Growers Association, which needed better roads to get their goods to market. At this time, there were no direct routes to Seattle. People in Snohomish had two options: through Cathcart, Maltby, Paradise Lake, Woodinville, and Bothell or across the marsh to the winding steep climb up Seattle Hill and over to the Pacific Highway. One suspects that possibly a fellow with some landlocked property may have fomented the discontent. This resulted in the Great Northern suddenly loaning its location engineer to find the best route. His route included a questionable grade that would cross the tops of the hills owned by C. D. Hillman. Hillman promptly donated right-of-way. Citizens along the route through Maltby filed a lawsuit, but the road was almost finished by the time there was a decision. It was concluded that the money used was for existing rather than new roads, so it was declared an existing road and other funds were used to complete the connection to Turners Corner. The road was locally called the Cut-off (or Woodinville Cut-off or Snohomish Cut-off).

Snohomish Logging neared the end of its harvest area and one of the partners had sold his holdings to George Miller. A Florence Logging crew moved into a new camp nearer Maltby and began construction of a logging railroad stretching from the Snohomish River Log Dump to Redmond. They finished and moved on to set up things for Miller Company's logging at Sultan and Lake Roesiger. Meanwhile, their Maltby manager was selected to head a company in 1925 called Siler Logging. It was financed by Port Blakely Mill and Weyerhaeuser, which both had timber in the area. Mr. Siler received one share of the company when it refinanced in 1934.

Atop the hills, a couple of stores and gas stations opened. The population seemed to change rapidly -- as did some of the merchants -- but there were also early settlers like DesMarais, Zanon, and Dalton who stayed. Snohomish residents continued to come out and bring help for the needy. It has been said, as late as the 1950s, that if your dad had a job you were considered a rich kid.

Confusion arose because all the new developments were within the Carthcart estate. Along the Cut-off the area was called West Cathcart, while the area below was called Lower Cathcart and Old Cathcart and near Maltby, Upper Cathcart. The West Cathcart people changed their name to Cathcart Heights, until a Civic Improvement Club contest chose the name of Clearview. The establishment celebration was Armistice Day, 1931.

The Great Depression and World War II

In October 1929 a financial depression began to grip the country. The Great Depression was hard for the citizenry of Maltby and surrounding communities, but not felt as severely, because they had been used to scraping out a living for some time. Federal programs such as Works Progress and the Civilian Conservation Corps provided employment in road construction and maintenance, school hot lunches, and the building of a gymnasium at Maltby. These projects gave work to younger workers who could help support their families.

As recovery took place, a well driller Oliver Willson moved into the old Florence Logging Camp. His son-in-law Vern Hodgson opened another store and gas station along Broadway. Area-wide people formed a Community Club and eventually built a clubhouse to replace the chicken houses they had used. Cathcart and Clearview Community Clubs were formed, but disbanded in a few years. Bear Creek and Horse Shoe Granges organized and built clubhouses. Youth activities such as 4-H, Scouts, Campfire, and Little League waxed and waned in the various settlements. The Sportsmen's Club property at Crystal Lake became the site for permanent homes during the Depression and became a gated community.

The location of a Boeing assembly plant in Everett during World War II induced a change in county zoning codes to permit more population density. The area clearly was becoming a bedroom community. A light industry area was approved at Maltby where the George Stevens claim gradually filled with businesses, as well as along Broadway Avenue. Two new schools were built.

Maltby and Neighbors Evolve

A fire protection district formed in August 1946, the services growing from a volunteer department into eight stations that in 2015 are staffed by full-time employees who also provide emergency medical treatment. Pope and Talbot platted their land around Echo Lake and Lost Lake. A State Highway (SR 522) traversed the area from Bothell to Monroe in 1963. The interchange served a golf course, small store, and more housing developments.

The highway displaced a large dairy farm near Grace. Poultry farms and berry fields became auto recycling yards that later became business parks, a Costco store, and a King County Sewage Treatment Plant called Brightwater. Sween Manufacturing had made Single Hen Batteries and Freezer Locker units at Turners Corner. The corners were filled by a power substation, two small markets, one with a gas station, and another corner with a marijuana shop.

A rail line from Snohomish to Woodinville was operational through Cathcart, which had one small store and a real estate office. The schoolhouse was replaced by five homes. Clearview had a closed county garbage dump, four strip malls, one church, auto and metal recycling yards, a wrecker service, some landscaping and marijuana places along Highway 9, but continued to be mainly residential.

Lake Beecher remained rural. Although the dairies were gone, Bob’s Corn & Pumpkin Farm (Bob and Sarah Ricci) became a popular Halloween destination. A co-op used some of the Ricci farm and hot air balloonists landed in their fields. Bob Heirman Park was established as a county wildlife and fishing sanctuary along the Snohomish River at Thomas Eddy.

One of the area's well-known attractions is the Maltby Café, which has been operating under present ownership since 1988. Located on Maltby Road in the basement of the 1937 Depression-era gymnasium, the restaurant is consistently a winner, or near the top, of many "Best of" restaurant lists for the Seattle area.