When Walt Sickler (b. 1927) was promoted from line crew foreman to Supervisor of Overhead Construction at Seattle City Light, he brought to the utility's management his knowledge of field operations and his leadership skills. One of his collateral duties was that of labor negotiator, which tested him in the mid-1970s. In this interview conducted by HistoryLink.org staff historian David Wilma, he recalls some of the labor relations issues during the administration of Superintendent Gordon Vickery (1920-1996).

The Interview

"In 1973, I was appointed to what's called Overhead Systems Supervisor and I was in charge of the line service crews and the street lighting. But I just had that job for a short time because the General Supervisor for Overhead, his name was Bob Stinson, passed away. And so in May of 1973 I became General Overhead Systems Supervisor.

"Then about that time there was a major reorganization of City Light. The superintendent at that time [Gordon Vickery] wanted to both consolidate and make some changes. He wanted all engineering to be in one division, rather than through other divisions. The Operations Division with the Line Division I was in, encompassed all the operating employees in City Light, around 1300 employees. That was everything from the Skagit to the Distribution Division. So in the reorganization they divided the Operations Division into the Distribution Division and Operations Division. I came under the distribution side, Manager of Overhead Construction.

"I was on the committee that did the reorganization although I don't think I profited from it. It was an interesting job to get involved in all the inner workings of City Light and determine the functions that all the divisions did, that could be consolidated or changed. As a result of that division, I became a manager.

"One of the first things that happened was that I was appointed as a labor negotiator for the City Light team to be with the city personnel at the negotiations for the various unions that City Light deals with. I think at that time there were in excess of 20 unions that we dealt with.

The New Superintendent

[In 1973, Mayor Wes Uhlman appointed Seattle Fire Chief Gordon Vickery to be Superintendent of City Light]

"He was what everybody deemed as an outsider and of course he was a fireman and we had a difficulty equating what a fireman knew about administering a power company. You think in your own channels that somebody to be your boss has to know what you're doing, but what you have to know is that when you get to a certain level it's more administrative than functional. I don't think it was his abilities because he did an outstanding job as Fire Chief. He modernized the Fire Department. I don't know if any people give him credit, but he's the father of 911. He started the Medics [Medic One] in the city and that was no small task. That's nationwide now.

"It wasn't so much his knowledge, but the mayor at that time wanted to make some changes in the administration of City Light, or at least the answering of, who they were responsible to. City Light was quite an independent department, starting back with J.D. Ross. Sort of stood aloof and far-off from the city functions. It was the mayor's intent that it be more accountable to the city. Vickery, we don't know what his marching orders were, but it sounded like he was sent over there to clean house at City Light and get it back in shape.

He was a very brusque and energetic and outspoken guy and he made some comments that bothered a lot of people. A lot of us in the lower ranks of supervision thought there could be some changes in City Light, certainly to meet the demands of modern days. [But] when your character is challenged, then that bothers you. He referred to City Light as 'a bunch of goof-offs.' No doubt, as in any place, there are ones. He came in kind of as a storm trooper and of course he riled up. One of the rile-ups was in the Line Division. He subsequently had a 10-day walkout in his superintendency.

"I know in the lower areas there have to be changes, but you need to find out what's going on in the system before you try and change it. Vickery acknowledged that in his later time, when I personally took him around to line crews so he could visit with the crews. He was very impressed by both attitude and capability in the crews. One of his admissions was that he had made an error in coming over and assuming that everybody needed squaring away.

The Coffee Break Incident

"There were directives regarding the conduct of the crews and such as that. There was one that when the crews completed a job they were to return to the shop and resupply their trucks and discontinue the practice of stopping somewhere to kill time until time to go in. It was reported in the White Center area that there were two crews that were stopping regularly in the substation. I was the manager of those crews at the time so I investigated it. I talked to the foremen and, yes, they admitted they had been stopping there and they would drink coffee for 15 or 20 minutes before they came in.

"I reported back to my immediate superior, Ken Hunich, who talked to the Assistant Superintendent Julian Whalley. The word was back from Mr. Whalley that they were to receive three days off. When Mr. Hunich reported that to me I indicated that if you require that, it's going to cause some real problems with the Line Division. Line crew foremen hadn't been disciplined before. And the word came back that they would receive the three days off. So I went down and told the two line crew foremen that they would receive three days off for misconduct. Their reaction was, 'we don't have to put up with this.' They walked out the door, got in their cars, and went down to the union hall.

Strike

"Word like that travels quite rapidly and suddenly all 600 electrical workers walked off the job [April 12, 1974]. It was strictly a decision of the assistant superintendent [to require three days off]. I doubt if Vickery even knew about it. The first thing Vickery knew about it, when they had the walkout, I met with him and a couple of the shop stewards and the union representatives. Actually the union representatives did not believe that was the way to resolve it. While we were in Vickery's office, the thing really broke loose because there were several departments at City Light that were very anti-Vickery and they figured this was an opportunity to get him roasted. So, they pulled a walkout on everybody else at City Light that would walk out. Just from the line crews going out, which I think we could [have] resolve[d] in the office that day. Then about two-thirds of City Light walked off the job.

Then it became a bigger issue. Just the line crews, that's when they made their protest, they marched on City Light. The chant that went down the street, 'We want Vickery!' Vickery was at the root of that particular thing and it escalated beyond the line crews. The line crews felt they had some injustice for that and they were using that means of showing their protest, but I don't believe that they had any intentions of prolonging it.

"I think the big part of the revolt was in the upper management. They were seeing that their sphere of dominance at City Light was being challenged by bringing an outsider in. City Light was kind of a close organization. The superintendents for the most part, other than Doc [Dr. Paul] Raver. [He] was quite a public power official, very well respected. All the others, John Nelson and those, all came from City Light.

"It got pretty ugly there when they marched on the Light building, the protests were getting quite, not violent, but protesting. There were some cool heads that said, 'We need to keep these people organized.' The primary ones was Larry Christensen and Miles Chamberlain and Gale Worth. They were, I believe, line crew foremen at the time. Miles was a dispatcher.

"They rented a large hall down at Seattle Center. Rather than people milling around places, they asked everybody to come down there. They had various speakers in. I'm sure they came in and talked against some of the policies and the change since Vickery came in. It gave them a chance to air themselves there. They finally came up with some demands and when they were transmitted to Vickery, Vickery responded by agreeing with, I believe, 10 different issues, forming an unbiased committee to look into these charges.

Settlement

"He called me into his office and said, 'I have here a list of things I'd like to be presented to the walkout people down at Seattle Center. I'd like you to take it down and announce it to them.' I says, 'You got to be out of your tree. A lot of the people equate the fact that I gave the men the time off. I'm part of the responsibility.' He said, 'No, that makes you the ideal person to go down.' And I did. I went down and they treated me very courteously and I told them in Vickery's words what he wanted to convey to them, that he would agree to this committee to meet. I got a standing ovation from the people, because they wanted a reason to come back. They had their pride, but once they got to a point, they had to stay until something broke. In fact, the old line crew foreman, Bob Whitlow, I had a lot of respect for old Bob, he came up and threw his arms around my neck and hugged me. He said, 'We're glad it's over.'

Lessons Learned

"The electrical workers maintained vital systems. They didn't vacate the service dispatcher and the power control center, the very nerves of City Light. Of course, things were restricted in responding to outages. We hastily had to get supervisory people together to be able to respond to outages that would occur. Cars hitting poles, all those things went out even during the strike. We got caught flat-footed, but after that was over we did establish emergency procedures for work stoppages and such as that.

The International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers Strikes

"It came in good stead because [on October 17, 1975] they had an electrical workers' strike. At that time, they, in a sense, paralyzed us, the dispatching, the power control center, workers at the dams, everybody walked off the job. We did have a system in motion and I guess to their dismay it worked very well, because for the 89 days of the strike, we maintained through all outages, fires, explosions and storms. We actually maintained the system in such an adequate state, there was very little pressure from the city to settle the strike.

"We got permission from Vickery to go talk to every member of the city council. Which was an unusual thing, to talk personally to city councilmen. Ivan Holbrook and I went over and talked to each individual councilman that would listen to us. Because the council was taking the attitude, 'We'll just fire the whole flock of them and start over again.' We were getting pretty worried about that, because you cannot fire that many people and start over again. I believe we changed the attitude of the city. Although we were running the system, Holbrook and I told them, if the city isn't being up front in wanting to settle this strike, we are not going to maintain it. We're getting tired. We could very easily have said, 'We can't do these things, but we're doing them.'

"We only used people who were not represented by a union. We didn't use engineers that were in the union. We used the supervisory and the non-represented people. The vast majority of supervision and middle management people of City Light in the Operations and Distribution divisions were former crew people from the field. They had outstanding abilities and were able to do those things.

Supervisors Fill In

"We put in long hours. We had cars hit poles, a major storm, a fire downtown under the viaduct. George Rouse, who was underground supervisor, was very instrumental in getting power back in to City Hall. And then we had a major explosion at a substation. I took a crew out there of supervisors. We installed a temporary substation to replace a 6 megawatt system out there in three days. The bombing at the Laurelhurst substation [January 1, 1976].

"I really think that was the thing that broke the hearts of the union people, they figured if we could do something like that. There were in a sense somewhat of a victim. Once it gets to a certain point, they don't have any control over it. Shortly after the explosion at the substation, we did negotiate a settlement.

"None of these things I referred to, the fire, the explosion was the result of any type of sabotage of City Light workers. The only thing that I recall that they did is when they went off the job, a bunch of them stuck toothpicks in the ignitions of their vehicles. That made them difficult to start. They did no sabotage to the system at all.

"As the strike went on and things got more testy between us, they did become more irritated and they followed us to the job and reported us that we didn't do things we should as far as safety. It was kind of a general harassment. But it got to the point that instead of being quiet about where we were going to the next job, we just told them. It kind of took some of the starch out when we weren't so secretive.

"In fact, we'd have coffee with them afterward. There was no animosity between us, we just had different positions. The hard part, I had worked with some of these people for many years and it was not easy to see them in that state. They would say, 'How can you do this to us?' I said, 'Well, when you change jobs, you change your position. I'm a role-player. I'm acting as a manager. When I do this job, I have to do it in accordance with that.' At the very last, they did mass picketing. I'm so grateful that they hadn't thought of that sooner. That was probably the most harassing thing. They would mob you as you came into the facility and had the police hold them back.

"We had a meeting with the Police Department and the Police Chief told us, 'We can keep these people back as far as you want, but your best bet is to let them get as close as you can stand them because they have a chance of venting themselves. The frustrations of keeping them back, then you get the violence.' And so that was the practice we adhered to. They would thump on the hood of the car as you went in and those things. After they had their say, they would back off. That was nerve-racking and that happened only the last three weeks of the strike.

Director of Operations

"Bob Walker retired in January of '78. They had an examination to replace him as Director of Operations. I applied and about three weeks after the thing closed they notified me that I didn't have sufficient supervisory experience. The job required a degree in engineering, but you could augment that with two years of supervisory experience for each year of engineering. I shrugged it off with, 'I guess that's that.' Then I got a call from the Assistant Superintendent, Joe Recchi, he said, 'You had many years as line crew foreman which was equal to supervisory experience.' Up to that point, I could honestly say I didn't really know that I wanted the job, but being as I was put in the spot like this, I had to perform. As the results of that, I was selected as the Director of Operations.

"I had approximately 500 people, ranging from the maintenance and operations, the dams, the substations, the shops -- paint, carpenter, electric, steel, over 800 pieces of mobile equipment (I have to say we were allowed to buy the best in equipment) and substation, communication, and relay. It was a good-sized organization, but I have to say that I was fortunate enough that I had four managers that took care of each of these four divisions that did outstanding work.

"I had been offered the Division Director's job when they formed the division, but I declined because I felt that I had not been in management that long. It didn't make Vickery overly happy. He said, 'Sickler, you have to extend yourself beyond what you think you can do to get anywhere.' As the results of that, I was on the negotiating committee and I did a lot of other training that I was allowed to pursue.

"It was a tremendous change because I had come from overhead distribution where I had worked on overhead power lines and had nothing to do with dams and generating plants and substations. I kind of learned the same thing Vickery did. You don't have to have intimate knowledge of things you have control over, as long as you have the ability to encourage people and to put people around you who can do the job.

The Skagit River Dams

"I got a special appreciation for the generating facilities. They were remote from the city. Sometimes I think that was to their advantage. I think they felt that they were kind of neglected. The only time [they heard from us] was when they were under criticism and something happened. I took a particular interest in it because it was intriguing to talk to the operators and the various people working up there. I found that those Skagit people were a very dedicated group of people. [Three Seattle City Light dams on the Upper Skagit River in the Cascade Mountains are located in southeast Whatcom County along a 7 to 8 mile section of Skagit River. They are Gorge Dam, Diablo Dam, and Ross Dam.] And they [the Skagit people] really liked the fact that somebody at City Light showed an interest in what they were doing as well as 'Just send the power to us.'

"After the construction of Boundary Dam [on the Pend Orielle River in Northeastern Washington near the Idaho border], there were two large metal buildings. They must have been 100 feet wide and 600 feet long. They were huge buildings. The manager of the Skagit, Bill Newby, came to me and said, "I'd like to have something like that." Between him and the manager of the shops, Harold Tufts, they had the steel workers under Tufts's control, they can go over and disassemble that building and then bring it over in the spring over the pass and reassemble it over at the Skagit. We talked to engineering and they said, 'It's too much of a hassle. We don't think you should do her. It wouldn't work.'

"Well, they didn't know those two managers and the ingenuity of that Skagit. Skagit people kind of remind you of Seabees [U.S. Navy Construction Battalions]. It's a can-do group. The less you tell them that they can do, the more they can do. Through conniving, they did get some engineering information on bases like that, how to build it stronger than it should be. Subsequently they moved the building over to the Skagit and erected it at the service center.

"At a staff meeting, Tom Rockey, head of engineering, my coworker said, 'I have to report that Sickler's group have constructed a building that's illegal and contrary to engineering practices.' [Assistant Superintendent Malcom MacDonald] who was an ex-Seabee, he just looked over at Tom and said, 'Thank you Tom.' We got the building without any problems.

"We had some really capable engineers at City Light. Sometimes I wondered why some of them stayed there, because I'm sure they could have done better at other places.

Automation

"The automation [of generating stations] had taken place, but we still had a lot of quirks in it. It's kind of a awesome, scary thing when you think that at 4:00 or 4:30 in the evening, those generating plants are all abandoned. There's nobody in them. Subsequently, you have to have people on standby and of course control from the Power Control Center. We had the quirks and the worms to iron out to make sure that people available on a moment's notice to go up and operate the plants. I believe City Light did an awesome thing in being able to convert all those manually operated systems from Cedar Falls, to the Skagit, even the Boundary, which is, what, 400 miles away. They're all automated. Even in the daytime, when an operator was there, the dam was actually under the control of the Power Control Center.

"The more difficult thing was Ross Dam. To get to Ross Dam, you had to go up to Diablo and get on a boat and go up, all the way up Lake Diablo up to Ross Dam to get up there. And the weather sometimes is quite severe. There were quite a few stories of operators getting up to the dam.

Steam

"The Lake Union Steam Plant was, on paper, a moneymaker for City Light because it gave the capability of having standby generation, which helped us in our rates with Bonneville. We could, supposedly, under an emergency, inject that amount of power into the system. It was a valuable asset.

The reality was, environmentally, the Lake Union Steam Plant was difficult to operate. It required a crew to maintain it and it was pretty archaic. In one instance when we found PCB [polychlorinated biphenyls - a toxic substance] in the Bunker C fuel oil caused quite a problem to get that out of the system and out of the city. I think it was around $5 million.

Women Join the Line Crews

"I was the manager of overhead and under my responsibility, they brought in ten electrical worker trainees. This was a group of women who they had screened and brought into that position and so I had to work with their coordinator. And then of course with their supervisors to set up the administrative part for integrating these women into the system.

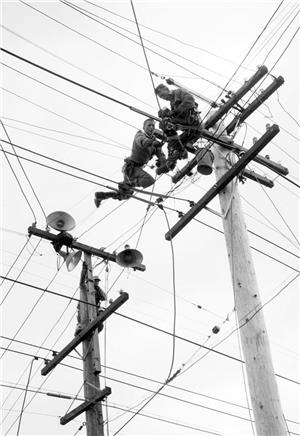

"What was more difficult was actually integrating the females into the crew structure. They were male-dominated, but I guess it was just the physical aspect of it, the requirements they had on line crews. There were some difficulties in making this change-over. It was the difficulty of bringing them into such a labor-demanding job as a lineman helper. We tried to work out the fact that there's a lot of physical difficulties doing that work.

"The line crew work is very physical. That's why we had that rope test pulling that weighted rope through a pulley for a period of time. Just the physical aspect of raising a crossarm up a pole. A crossarm might weigh upwards of a hundred pounds. You have to overcome quite an inertia to pull that up through a pulley. Just the shear physics of it, if you don't weigh hardly any more than that crossarm, you're going to have a hard time getting it up the pole. It is very physical.

"Then there was the fact that there were just men on the crew. Some of your personal things you did on the crew easy to take care of because there was no women around. It was strictly the physical aspect. They had difficulty. Of course on a crew, it's a joint operation. Each lineman had a helper. If another lineman was doing something that maybe two helpers might have to go help, then you went over to help him. And because of friction that developed, sometimes maybe not in the best words, somebody sees a woman struggling, 'Can I help you?' 'No, don't you think I can handle this myself?' 'Sure you can handle it.' So, he'd walk off and let her do it. That creates problems. When they really did need help there was nobody to help them. Those type frictions built up.

"Some of those trainees went into different departments. Patricia Eng (1947-2007) ended up over in the Meter Division and I believe she became a crew chief. I recall her as very much a success. Heidi Durham was quite a controversial person, probably very talented, but she got injured falling off a pole, and subsequently had some paralysis. She ended up in the power control center.

"It was kind of a rough row of them coming into that particularly difficult part of our system. I believe there has been a lot of success, a lot of good women working at City Light.

[Regarding a 1983 report critical of City Light for instances of racial and gender discrimination:] "We had ongoing situations, with an organization our size. City Light is one of the most integrated as far as minorities and women into the operating workforce, into the crew workforce. There no doubt were varying number of both harassment and discrimination things. I didn't recall that there be any specific times where it was greater than others.

Vickery Leaves

"[Mayor Charles Royer] made a campaign promise to dump Vickery. Then the tables were turned. I honestly believed that a poll of City Light indicated that in the latter part of Vickery's administration they preferred him to stay, the City Light people. I think they had come to understand that he kind of got his feet on the ground and really got a knowledge of what the system was like. But Royer made a campaign promise.

"I was at the staff meeting when he fired Vickery. But Vickery had a contract. Vickery didn't have to go. But I think ... he chose [to leave] rather than cause problems. I recall that Vickery didn't have to go peaceably, but he chose to go peaceably. He did have a contract.

Audits and Reorganizations

"Instability arises from constantly trying to make changes in the system. Of course we had to go [to] automation and then we had to be able to justify our budget by justifying the number of hours it takes, right down [to] the tightening of a nut on a transformer. I think some of them went a little too far. It took some of the responsibility and accountability away from the supervisors by determining what persons should do rather than supervisors having a better knowledge of it.

"I used to have a saying that reorganization gets you away from having to justify what you are doing. Because you always have to have some historical data before you can be accountable for what you have done. If you go in and do some reorganization, then you can't be held accountable for a period of time, because you need to be able to get this data assembled so you can justify your change. I wasn't a fond participant in these management studies.

Looking back at 40 years

"I've seen some tremendous organizational changes at City Light. Some for good, some for bad. It seems to go around in circles. I understand it's back around now where it was years and years ago. I've seen City Light modernize. Some of it came under Vickery just like at the Fire Department. We were allowed to buy the best of equipment. City Light was a very safety oriented company.

"As with any organization, it's the people. City Light was fortunate in that it had outstanding people work for it, some through adverse conditions. It's a plum for the city to have. I think they have misused it somewhat over the years. I think that environmentally and some of their social programs, I think they have used City Light as a bulwark for funding them. Some for good. I think especially on the environmental side, not being able to raise Ross Dam, not being able to build Copper Creek. Those were all internal things. I think we could have overcome those. It's hard to have people fighting in your own organization to keep you from doing those things. I think that City Light was kind of the golden egg for the city of Seattle. It's been a real asset to the community because of the low-cost power that they have supplied for years. I think it did get misused some in their environmental programs and some of their social programs.

"I was probably one of the most fortunate people there. I was limited in education in the sense of formal, but I was given the opportunities and I think I seized on them. I was fortunate to be where I could move ahead in the company and be part of the system. I think I contributed a lot. As with anything else, you never become so much a part of the system that it can't do without you, because I don't think they lost a stroke when I left there. I enjoyed my career there. I make the facetious remark that, 'After 40 years, they needed a change and so did I.' "