Mary A. Latham was Spokane's first woman physician -- a heroic and ultimately tragic figure in the city's history. She came to Spokane in 1887 and specialized in the diseases of women and children. She was considered nearly a "patron saint" of Spokane's poor (Illustrated Annual). She was one of the founders of the Spokane Public Library and the Spokane Humane Society. However, her life took a downward turn in 1903 when one of her beloved sons died. In 1905, she was arrested and convicted of arson when she set fire to a store in order to keep it out of the hands of a rival. Sentenced to four years hard labor, she escaped into the Idaho woods but was found after a seven-day manhunt and sent to the state penitentiary at Walla Walla. She returned a broken woman and died in 1917. Yet today she is honored in Spokane for the good she did in the first part of her life.

A Woman in Medicine

Mary Latham was born Mary Archard (some sources spell the name "Archer" or "Archerd") on October 18, 1844, to James and Jane Archard in New Richmond, Ohio. Theirs was a prominent pioneer family with many accomplishments. One of Mary's sisters, Eliza Archard Conner (1838-1912), would go on to become a celebrated writer for the Saturday Evening Post and a well-known suffragist.

Mary Archard married Edward H. Latham (1842-1928) on July 28, 1864, and they had three boys, Frank (1866-?), James (1870-1903) and Warren (1872-?). After raising the boys, Mary chose a career in medicine, rare for a woman of her time. She enrolled in the Cincinnati College of Medicine and Surgery and graduated in 1886 as part of the first class of women admitted to the clinical wards of Cincinnati General Hospital (Edwards, 394). Edward also decided to enter the field of medicine. He attended the Cincinnati College of Pharmacy and, in 1884, he graduated from the Miami (Ohio) Medical College. Mary and Edward practiced together briefly in Cincinnati.

But soon, unspecified health problems compelled Mary Latham "to seek a more salubrious climate" (meaning drier) and in 1887, she and her three boys moved to the burgeoning town of Spokane Falls, soon to be called just plain Spokane (Edwards, 394). The plan was for her husband to close his practice and follow, yet their marital problems may have already been simmering, because he tarried another two years.

Sought-after Specialist

A woman physician was unheard of in Spokane. One account says Latham was the "first woman physician to practice medicine" in all of Washington Territory, although this is difficult to verify since Washington did not start licensing physicians until later (Bragg, 130). She opened a home medical office at First Avenue and Stevens Street in downtown Spokane and later opened an office in the Frankfurt Block. Her husband Edward finally arrived in the summer of 1889, just days before the Great Fire of Spokane wiped out a huge portion of the city's business district, including their office, on August 4, 1889. Two days later, the Lathams ran an ad in the Spokane Falls Review announcing a new makeshift office and dispensary at their home ("Resuming Business"). Later they opened a new office nearby in the Blalock Block on Stevens Street.

Mary quickly established herself as a sought-after specialist. She delivered countless babies and helped hundreds of women through difficult pregnancies. In 1889 she was already being extolled as a paragon of good works in the community. A Spokane Falls Review correspondent accompanied her on her rounds and wrote, "Our pioneer lady physician is one whom Spokane may well honor. Her record as a lady and Christian, doing good deeds ... is incomparable. The smiles that lit up the sad faces as I passed with her through the Sisters' Hospital (Sacred Heart) told more plainly than words can tell that she was a frequent and welcome visitor. Mrs. Latham is an earnest worker in home mission fields and never gives up on a good cause" ("Our Beloved ...").

A newspaper profile of Mary Latham in 1892 said, "[I]n her special line of work -- the diseases of women and children -- she has no superior in the state" (Illustrated Annual). The profile was even more complimentary of her character:

"In nearly every community there is one who is a mediator between the wretchedness and wealth, a person whom the affluent respect and the needy love ... such a character is Dr. Mary A. Latham. Probably no woman in all Washington has so many friends as she. Many of the poor into whose lives she has thrown sunshine regard her as their patron saint" (Illustrated Annual).

Latham dreamed of opening her own private hospital for women and children, and she briefly realized that dream in 1893 when she opened the Lidgerwood Sanitarium.

Community Spirit

Latham's community spirit was by no means confined to medicine. In 1890 she wrote a letter to the editor of the Spokane Falls Review proposing a new community institution -- a public library. She wrote that a library would contribute:

"the greatest good to the greatest number ... Our children, in whom the craving for knowledge is innate, can then be learning something good, or at any rate, can never remain ignorant for the lack of opportunity for learning" ("For a Public Library").

She went on to offer, "as a starter," a complete set of the Encyclopedia Britannica, "nicely bound" ("For a Public Library"). From this beginning, a subscription library arose, and Latham was elected to its board. It eventually evolved into the Spokane City Library in 1894 and then in 1901 into the free Spokane Public Library, a civic institution that endures to this day. Latham also was an early proponent of the Spokane Humane Society, serving as its secretary and treasurer, and one of the founding officers of the Spokane Horticultural Society.

And she followed her sister's lead, becoming both an author and active in the suffragist movement. In 1891 she wrote a short story titled "A Lonely Christmas" for The Spokane Review. It was a melodramatic tale about a prospector who makes a lonely Christmas trek through the snow to bring assistance to his ailing son. A kindly Indian comes to their rescue. She also wrote essays about health and hygiene for woman. As an activist in the suffragist movement, she was elected the local chair of the Queen Isabella Association, a progressive organization for professional women.

With all of this energy and accomplishment, she was considered nearly a civic treasure. One of her fellow medical practitioners was quoted in 1892 as saying, "I believe that Mrs. Latham's career, as brilliant as it has been in this city, is only beginning, for with her indomitable energy, she will go on until the highest success is hers" (Illustrated Annual).

Veering Toward Tragedy

This prediction would prove to be almost completely, and heartbreakingly, wrong. From this point on, her story veers inexorably toward tragedy. Perhaps the first seeds can be seen in the breakup of her marriage. Edward Latham never enjoyed the same professional respect, possibly because he was a heavy drinker. He eventually accepted an appointment in 1891 as the first government doctor at Nespelem on the Colville Reservation. It was a lonely and primitive outpost, funded only for a single man, not for a couple. This might have been part of the appeal for Edward, who was already evidently estranged from his wife. He went off to Nespelem and four years later filed for divorce, on the grounds that she had essentially deserted him in 1888. She denied the charge, but the divorce was granted in 1895.

Latham had also become deeply involved in a new, and to modern eyes somewhat crackpot, medical movement called the Biochemic System of medicine. It claimed that disease was caused not by germs or microbes, but by the lack of certain cell-salts in the blood. A Biochemic College was briefly established in Spokane, and Mary Latham was its teacher of obstetrics. The college was gone by 1895.

More ominously, Latham began to demonstrate an alarming lack of financial judgment and accountability. She started getting involved in dubious business and real-estate ventures, including a huge fruit orchard near Mead, just north of Spokane. She bought land and purchased thousands of fruit trees, grape vines, and berry vines. This and other ventures soon turned sour. Latham, once known for her generosity, was now being routinely sued over money. For instance, the nursery sued her for not paying for the trees in full, and then the man managing her orchard sued for back pay. As the decade went on, she was sued repeatedly over matters large (failing to pay for property she had purchased on contract) and small (failing to pay for a series of books she ordered).

Latham, grown increasingly strong-willed, dealt with these problems in two particularly unwise ways. First, she typically countersued everyone who sued her, although usually in vain. Second, and most ominously, she started transferring her property deeds to third parties, in order keep it out of the hands of her creditors. This was a strategy that would backfire in a spectacular way.

Then, on April 20, 1903, came the ultimate turning point in her life. Her 33-year-old son James, a brakeman on the Northern Pacific Railroad, was walking across the Spokane freight yards in the dark when a train approaching from behind struck him and fatally crushed his skull. James and Mary were particularly close -- he was still living at home at the time of his death. Mary never recovered from the blow.

Legal Troubles

From this point on, Latham's grasp on reality became more and more tenuous. In fact, many of her later troubles can be tied directly to the circumstances of James's death. James had died without a will, which became a serious practical problem for Mary, since James was one of the people to whom Mary had deeded some property. She later claimed she did so only temporarily, just for the duration of a long trip she took to the Yukon. Yet when she came back, she forgot to have James return the property to her. So when James died without a will, she was faced with the possibility of having to share that property with her divorced husband. Instead, she resorted to the blatantly unwise move of drawing up a deed, backdating it, and forging James's signature on it. This bogus deed transferred most of her property in trust to James Scribner, a miner she had met in the Yukon, and whom she apparently planned to use as a third-party shield against her creditors.

Further complicating the situation was the fact that after James's death, Mary Latham had appealed to James's fiancée, Jennie H. Johnson, one of several unwed mothers she had taken in after difficult pregnancies. Latham beseeched Johnson to come back to Spokane from Butte, Montana, where she had moved after James's death, and take care of Latham in her loneliness and grief. In exchange, Latham said that she would give Johnson all of the property held jointly by James and Mary, including 500 acres of land with a country store/pharmacy on it located in Mead. The day Johnson moved in, Latham transferred the Mead property deed to her.

A few months later, Johnson decided to sell the Mead property and discovered that Latham had also given Scribner a warranty deed for that property. Johnson went to court to question the validity of that obviously forged deed. Soon enough, Latham fell out with both Johnson and Scribner. Both emphatically denied Latham's claim that they had given her power of attorney to dispose of the property held in their names. A complicated series of nasty court battles ensued as Johnson sued for the rights to the Mead property.

Latham's defense strategies were ill-advised, to say the least. For instance, she produced several different "will forms" in court, purportedly written by her son James, yet they were easily revealed as "obvious forgeries written in Mary's flowery style" and with witness signatures in Mary's handwriting (Cochran, 199).

Latham also made the wild claim that her Mead store agreement was actually with an entirely different Jennie Johnson -- Jennie C. Johnson, another young woman who she said had also lived with the Latham family during her pregnancy. She claimed this Jennie C. Johnson was "a member of the royal family in Sweden" who had moved back to Europe and thus had no interest in taking over Mary's property ("Royalty Figures ..."). Latham's domestic servant quickly discredited this outlandish tale when she testified that the only Jennie Johnson who ever lived with the family was the original Jennie H. Johnson from Butte. Historian Barbara F. Cochran, author of a definitive biographical essay about Latham, wrote:

"The sad truth of the matter was that Mary simply could not understand how Jennie or Scribner had any claim to property she had bought and paid for ... They had not invested one cent. It seemed proper and reasonable for her to use the law for her own purpose, such as avoiding attachment for debts, but at the same time to ignore it when it suited her to do so" (Cochran, 200).

Latham realized she had gotten herself into serious trouble with these dubious strategies. She even made a trek to the prosecuting attorney's office in order to, in her own words, "find out what kind of jackpot I have gotten myself into" ("... Produces Will Form ..."). The prosecutor's reply was not recorded, but he may have reminded Latham of the laws against forgery and perjury. Unbowed, Latham remained stubbornly determined to thwart Johnson. She later told a friend that Johnson "would have to get up pretty early to beat Mrs. Latham," and said that even if Johnson won the case, "it wouldn't do her any good" because she would never take possession of the store ("... Serious Plight"). This sounded like a vengeful boast in light of later events.

Imprisoned for Arson

On April 29, 1905, the court ruled in favor of Jennie H. Johnson and awarded the Mead store and property to her. Before Johnson could take possession, however, a catastrophe occurred. In the middle of the night, on May 7, 1905, the Mead store burned to the ground. A stable boy, Melville Logan, discovered the fire after putting the horses away late that night. He told police that he saw Latham, standing across from the blazing building, fully dressed, watching silently and with what appeared to be grim satisfaction.

"Did she make an outcry?" he was later asked in court -- "None at all," he replied ("... Serious Plight"). When the panicked stable boy asked her if they should run and alert a neighbor Latham calmly said, "Let him sleep" ("... Serious Plight").

Latham knew authorities were suspicious and she immediately wrote a letter to The Spokesman-Review claiming she was home in bed at the time of the fire. She also made her housekeeper write another sympathetic letter to the editor, dictated by Latham, and signed with the fictitious name of Mrs. A. R. Smith. This letter also asserted that Dr. Latham was in bed at the time of the fire. It further asserted, "Dr. Latham is the victim of jealous enemies" ("... Was in Bed").

These protestations were in vain. On May 10, 1905, Latham was arrested for arson. The sheriff noted her "many contradictory statements," including the statements in the letters ("Sheriff Arrests ..."). By the time her trial started in June 1905, the evidence had piled up against her. She had clearly been busy the week before the fire, removing many items of value and stashing them elsewhere. The stable boy said she even had him move out a few more things just minutes before the fire started. Her defense was that she was home in bed, and knew nothing until a man pounded on the door, yelling about the fire. But the stable boy, her housekeeper, and several other witnesses refuted this version of events.

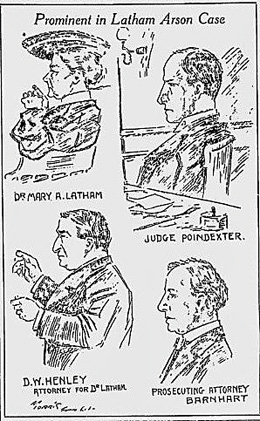

Following a dramatic and often emotional trial, the jury found her guilty of arson on June 18, 1905. Latham collapsed after the conviction and tried to starve herself and poison herself with drugs before sentencing. The judge had her brought in on a cot and sentenced her to four years of hard labor at the Washington State Penitentiary in Walla Walla. Because of her condition, the judge allowed her to return to a friend's home on bond until the sentence could be carried out.

Then, late at night on July 22, 1905, Latham lit out for the wilds of Idaho in a buggy, accompanied by her dog. She proceeded to drive the buggy over the back roads into the rugged mountains. Things quickly went wrong. One night, her horse ran off. She abandoned the buggy and all of her provisions and wandered the trails and logging roads on foot. A manhunt was launched, all over North Idaho, looking for a lone woman in a buggy. Latham wandered the timber with nothing to eat. At a lonely farmhouse owned by the Schraeder family, 60 miles northeast of Spokane, she asked for food. She was also sighted at several other farmhouses. Then the Schraeders woke up to find her back in their kitchen, fixing herself some breakfast. They notified the sheriff who soon took her back to Spokane, this time to jail.

Latham first claimed she had been innocently camping with friends and had no idea anyone was looking for her, then later confided that she had a plan to cross the Rocky Mountains into Montana, float down the Missouri on a houseboat, and escape to Mexico. She came closer to telling the truth in a jailhouse interview, saying she was suffering from mental shock, "a cyclone of force on the nerves, and the nerves collapse" ("Just Too Tired ..."). On January 9, 1906, she was sent to the Women's Prison at Walla Walla, and she served about 15 months of her sentence, until she was paroled because of poor health.

Final Years, Later Memorials

Latham came back to Spokane, broken in many ways, but still determined to practice her profession. Yet she was still dogged by lawsuits over money and property. She also reappeared on the front pages in one puzzling incident. In 1911 she was discovered in her own room, bound hand and foot to her bedposts, with a pillow containing chloroform tied over her mouth. She was groggy, but survived. She told police that two unknown men entered her room, ransacked it, demanded money, knocked her over the head, and left her for dead. Police made no statement about the case except to say that "it contained many mysterious features" ("... Drugged in Home"). It was never solved.

Later in 1911, Latham was charged with another felony: performing illegal abortions. She had been arrested for this before, soon after she got out of prison, but those charges were dropped. This time a 17-year-old delinquent girl told police that Dr. Latham had performed her abortion. Latham was released on bond, and the charges were dismissed after she agreed to "retire from active life" -- meaning from practicing medicine (... Order of Dismissal). She was, the prosecutor said, "in broken health" and her mental condition was "very much impaired" (... Order of Dismissal). Yet she still tried to help women and children when she could. In 1917 she agreed to take care of a 12-day old infant with pneumonia. She contracted pneumonia herself and died on January 20, 1917, at the age of 72.

Over the decades, the sensational aspects of her story began to recede and she was remembered mostly for the good she had done in her life. In 2007, the Fairmount Memorial Association erected a large stone monument engraved with her image at Greenwood Memorial Terrace, where she was buried along with her ex-husband. The original headstone said simply "Edward H. Latham and Mary his wife." The new memorial was far more fitting. It recounted her many accomplishments and re-established her position as a powerful influence, mostly for the good, in Spokane's early life.

Today, her visage gazes out over downtown Spokane at Riverside Avenue and Monroe Street. Her bronze bust is one of 12 sculptures honoring 12 of Spokane's founding fathers -- and mothers. Her inscription reads: "Physician. Essayist. Library Advocate."