Latinos, the largest minority in the United States at more than 13 percent of the population as of 2006, have been instrumental to the development of Washington state since the 1774 Spanish exploration of the Olympic Peninsula. The state's Hispanic population has increased dramatically, from 118,432 in 1980 to 549,774 in 2005. The foundation of the current Hispanic boom is rooted in economic and labor developments of the 1940s. (Editor's note: Although the term Latino is used throughout this essay, in actuality the Latino experience in Washington has been until very recently primarily a Mexican American and Mexican experience.)

Latino Pioneers

In Washington, the familiar names of the Strait of Juan de Fuca, the San Juan Islands, and Rosario Strait are a legacy of Spanish influence in the state. Spain formally claimed the Pacific Northwest in 1775, a year before the United States Declaration of Independence. The Spanish captain Juan Perez led the ship Santiago from the port city of San Blas, Nayarit, Mexico, to the coast of the future Washington state. The Spanish sent this expedition in response to other European claims to the area. Spanish expeditions from New Spain (present-day Mexico) were always composed mostly of Mexicans, not Spaniards.

The Spanish/Latino crew made four expeditions to Washington during the late 1700s. In the process, two settlements were established in the 1790s at Neah Bay (Nunez Gaoan) and Vancouver Island. Nunez Goana (est. 1792) was the first non-Native settlement in the state. It was the Mexican crewmembers of all four Spanish expeditions, rather than the Spanish captains, who were pioneers in the creation of the two settlements. Also, it was Mexicans, not Spaniards, who produced the first in-depth topography and scientific studies of the state.

Two Mexicans in particular contributed greatly to early knowledge of Washington state. Jose Mariano Mozino participated in the 1792 expedition, known as the Malaspian Expedition. He produced an ecological catalog of 200 species of plants, animals, and birds. He documented his research in Notcias de Nuka: An Account of Nootka Sound in 1792. Also a member of the Malaspian Expedition, Anastasio Echeverria was considered the best artist in Mexico at the time. Echeverria sketched one of the first detailed landscape profiles of the area.

The Spanish expeditions made many discoveries, but by the late eighteenth century, conflicts in Europe and Latin America forced Spain to abandon its claim to the region. In 1819, the United States and Spain signed the Adams-Onis Treaty in which Spain gave up its claim to the Pacific Northwest and sold Florida to the U.S. The area of Washington became Washington Territory in 1853, and became a state in 1889. Through it all, the Latino legacy remained.

Latino Mulepackers

Before statehood, Latinos contributed to the early economic development. After 1819 two economies developed in Washington: fur trapping and mining. Latinos were not instrumental to the trapping business, but they created the backbone of the transportation system for the mining economy of the late nineteenth century.

The Mexican mule-pack system was in regular use in the mining economy of California during the mid-eighteenth century. The discovery of gold in British Columbia and Idaho during the late 1850s prompted many miners to go through the future Washington state and stop there to purchase provisions. Before the 1870s, lack of commercial overland transportation hindered development of Washington Territory. Walla Walla was center of mining activity, and by 1870 had a large Mexican population, which developed the region's first dependable means of commercial transportation.

Mexicans mule packers were in high demand because of their skill. And since most non-Natives preferred mining to loading, most packers throughout the Pacific Northwest were Mexicans. The Mexican mule-packing systems showed its value during the Rogue River War in Oregon 1855-1856. The Rogue River War pitted Rogue River Indians against the army volunteers in Oregon. Mexican mule packers assisted the volunteer regiment in winning the war and securing American presence in the Oregon Territory. After the war Mexican mule packers were in high demand throughout the Northwest, up until the common use of the railroad in Washington by the late 1870s.

Permanent Settlement and Agriculture

During the nineteenth century, Latinos did not settle permanently in Washington in large numbers. Instead Latinos (mostly Mexicans) traveled to Washington as miners, ranchers, fur trappers, and to lead mule-packing commercial transportation. However, the political turmoil of Mexico during the most destructive years of the Mexican Revolution (1910-1917) influenced many Latinos to immigrate to the U.S. The agricultural development of Washington influenced many Mexicans and Chicanos (Mexican Americans) to settle in Washington during a time when their labor was in high demand.

World War II was the watershed moment of Latino settlement in Washington. The demand for agricultural labor in the state and the internment of Japanese Americans in areas such as the Yakima Valley created a labor crisis in the agricultural regions of the state. The solution was contracted Mexican labor known as the Bracero program and Chicano migrant workers. The term Bracero designated contracted Mexican workers in agriculture and later in the railroad industry from 1942-1947 in Washington, though it lasted from 1942-1964 nationally.

Although they were needed for the war effort in the state, Braceros were not immune to harmful treatment. While in Washington, Braceros experienced racism, poor housing facilities, and inadequate treatment from farmers. In response to their maltreatment many Braceros called on the Mexican consulate for protection and staged huelgas (strikes). Due to the growing costs of Braceros, the program ended in the state in 1947, but revived again during the Korean War (1950-1953).

One major consequence of the Bracero program was Chicano settlement in the state. The first wave of Latinos came from the states of Wyoming, Montana, and Colorado. The Utah-Idaho Sugar Company recruited a number of Chicano migrants to the state. A number of them settled in the Wapato-Harrah area, establishing one of the oldest Latino settlements in the Pacific Northwest. Wapato-Harrah during the war was a prime area for labor-intensive beet harvesting. After World War II, the agricultural economy of Washington encouraged more settlement of Latinos (mostly Chicanos), as farmers became dependent on migrant labor.

Eastern Washington. especially the Yakima Valley, was the first place of major settlement of Latinos, but by the 1950s Latinos began to move to the Puget Sound area and to the Skagit Valley. During the 1950s most Latinos came from Texas and California and began to settle permanently as Chicano labor replaced the Bracero labor of World War II.

There was a large change in the migrant circuit as more and more Latinos opted to settle in Washington. Although Latinos' work was welcomed in Washington, they faced discrimination. As in the Southwest, this led to confrontation during the late 1960s and 1970s. Latinos in Washington joined the civil rights movement and established a distinct movement of their own.

Political Activism and Latino Boom

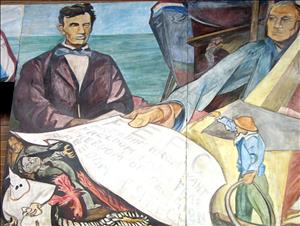

The Mexican American Civil Rights movement (Chicano Movement) developed in Washington following the movement started in the Southwest by Cesar Chaves and Dolores Huerta. Just as Washington was notorious for Bracero strikes during the 1940s, the state experienced the most activity of the Chicano Movement within the Pacific Northwest. Chicano farm workers launched strikes in the Yakima Valley, Chicano students in Seattle established a presence at the University of Washington, and Latinos in Seattle established the social services building, El Centro de la Raza, and later Sea Mar. In the Yakima Valley the Farm Workers Clinic (est. 1972) was founded serving migrant workers. Numerous Latino civil rights organizations emerged throughout the 1970s, including a muralist movement.

By 1968 the ripples of the civil rights movement in the South reached Washington. Chicano students in the Yakima Valley recruited by African American students from the Black Student Union at the University of Washington became active on campus. Influenced by the farm workers movement in Southern California and the Chicano Movement, the Latino students formed United Mexican American Students (UMAS). UMAS later joined with the national Chicano Movement and became Mecha (Movimiento Estudiantil Chicano de Aztlan). UMAS joined the national grape boycott of 1968-1970 and by 1969 was marching in the streets of Seattle for Latino civil rights.

From 1969-1970 the Yakima Valley saw a number of wildcat strikes by Latino farm workers. Many of the Chicano students at the UW participated and negotiated during the strikes. In the spirit of the farm workers movement led by Cesar Chavez, a United Farm Worker Co-Op in Toppenish was set up. Wildcat strikes in 1970 at Granger and Mabton targeted Yakima Chief hop ranches for better pay and working conditions. The strikes succeeded, though much of what the workers gained did not last.

As Latinos made strides during the 1960s and 1970s, an important event took place in 1965 to change the Latino makeup of the state. The 1965 Immigration Act eliminated racial quotas in the U.S. immigration system. This encouraged a change of Latino immigration into Washington from Chicano (Mexican American) to primarily Mexican immigrant.

During the 1980s and early 1990s Washington was the site of a short revival in the Latino farm workers movement. In 1986 Chavez visited the Yakima Valley and led a march for the improvement of working conditions. Also in the same year the United Farm Workers of Washington State became official. The movement culminated in the first union contract for farm workers in 1995 with Chateau Ste. Michelle winery, leading the UFW of Washington to join with the national UFW union.

As the Chicano Movement died down in Washington and across the U.S during the late 1970s, the Mexican immigrant population increased. During the 1960s, many Chicanos left the migrant farm labor circuit, and during the 1970s, many left farm work altogether. In an ironic twist, Mexican immigrant labor supplanted Chicano farmworker labor and low skilled labor altogether.

Just as the early twentieth century ushered in an era of large Latino immigration into Washington, so did the end of the century. The Latino immigrant influx increased during the 1990s as Latin American countries experienced economic and political turmoil, especially in Mexico.

Most Latino immigrants settled in older Hispanic communities of the Yakima Valley and Eastern Washington, but others moved to areas such as King Country. By 2004, King County's population of 1,793,583 was 6.5 percent Hispanic or Latino -- close to 117,000 Latinos live in the county, illustrating a Latino community that favored urban areas.

Latinization of Washington

An observer traveling through the Yakima Valley, Pasco, Burien, or Mount Vernon will notice an undeniable Latino influence. In the Yakima Valley alone, from Wapato to Prosser, Latinos make up [in 2006] the majority of the population. Yakima County as a whole has a population of 231,586, of which 38.6 percent, or more than 89,000 persons, are of Hispanic or Latino origin.

The presence of panaderias (bakeries), taquerias (taco restaurants), and Spanish radio stations are as common or more common than their English counterparts. What this means is that Latinos are becoming the foundation of communities that were previously Anglo American based. In Wapato, many Latinos are still farm workers but many have become farmers themselves. In addition, the city had a Latino mayor, its highest-grossing businesses were owned by Latinos, and the town was more than 76 percent Latino. In 2004, Latinos comprised 8.5 percent of the entire Washington population.

The 2006 visit by Mexican President Vicente Fox to Yakima and Seattle illustrated a growing Latino presence in Washington during the twenty-first century. Although President Fox came only to talk of trade with local leaders, his visit gave additional attention to Latino residents. In addition, the immigration rights protests of the same year showed a Latino population as active community members in the state.

April 11, 2006, was a historic day in Washington. More than 15,000 people marched in Seattle for immigrant rights. The majority were Latino residents, both U.S citizens and undocumented. This historic rally was followed by one on May 1 in Yakima, which is considered the Latino center of the state, and once again in Seattle. The marchers responded to legislation that would criminalize illegal immigrants and fortify the U.S-Mexico border. Marchers instead pushed for a clear path to citizenship, assistance in uniting families of undocumented residents, and ensuring workplace and civil-rights protections.

Many residents consider Latino issues to be a recent phenomena but, as we have seen, Latinos have a long history in the state, and since 1970 have been the largest minority. Latinos still face major challenges similar to issues that arose during the Chicano Movement. Latinos are disproportionately affected with high school dropout rates, poor housing, poverty, and minor political participation.