The Latona Bridge, built in 1891 for Seattle pioneer and investor David T. Denny (1832-1903), carried the first streetcar line across Lake Union and was the first substantial bridge to cross the lake proper. In 1901 the Seattle Electric Company added an adjacent span dedicated to streetcar traffic, with the old bridge reserved for use by pedestrians, horses, and vehicles. In 1917 the pending completion of the Lake Washington Ship Canal required that both spans be modified to open for vessels, a task completed shortly before the canal's official dedication on July 4 that year. Two years earlier, Seattle voters had approved the sale of bonds to finance a new drawbridge at the site, and construction of the University Bridge, after some early missteps, was completed in June 1919. Within weeks, the Latona Bridge, part of which had been serving the public for nearly 30 years, was demolished. In 1932 and 1933 the University Bridge was widened, the approaches rebuilt, and its timber decking replaced with an open-grid steel surface. Computer and electrical upgrades were completed in 2014, and the span is expected to endure into the foreseeable future.

Settling Lake Union's North Shore

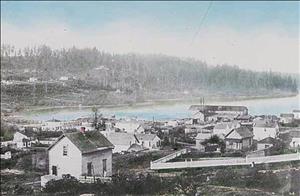

In a single decade, Seattle's population exploded, from 3,533 recorded in the 1880 census to 42,837 in the 1890 count. The areas of the city that could be reached without crossing water were rapidly filling, and by the early 1880s settlers and businesses in increasing numbers had staked claims on the south, west, and east shores of Lake Union. The north shore still was reachable only by boat, with the exception of the Montlake isthmus at the lake's eastern extremity (named Portage Bay in 1913).

In 1885 a horse-drawn streetcar line reached south Lake Union, and by 1887 steam-powered launches were carrying passengers to the new neighborhoods sprouting up on the lake's northern shore. The land recently had been cleared of its merchantable timber, and the pace of settlement steadily picked up. Among the new communities were Fremont, Edgewater, and Latona (part of today's Wallingford), and Brooklyn (today's University District).

The First Latona Bridge

David T. Denny was the first member of the famed pioneer family to set foot in the future city of Seattle. After decades of engagement in various business activities, in 1884 he became principal stockholder of the Western Mill Company on the south shore of Lake Union. The following year Denny and several other local businessmen who owned property on or near the lakeshore formed the Lake Washington Improvement Company, and in 1886, using mostly Chinese labor, completed a shallow channel between Lake Washington and Lake Union. Timber locks were erected that enabled passage only of very small boats and logs to feed Denny's mill. Known as the Portage Canal, it bisected the Montlake isthmus, which had been the only natural connection between the land north and that south of Lake Union.

It was obvious that if the land north of the lake were to be developed, people would have to have some way of getting there other than by boat. On August 5, 1890, Denny (joined by a different group of investors than that involved in the Washington Improvement Company) petitioned the King County commissioners to supplement $3,550 of investors' money with $2,550 of public money so that "the work could begin immediately" on building a bridge across Lake Union at its narrowest point ("To Bridge Lake Union").

The Seattle Post-Intelligencer reported that the bridge would extend "from Denny's point on the east side of Lake Union to Latona," and would have "a 100-foot cantilever span in the center, capable of being transformed into a draw at any time should a ship canal be made to Lake Washington" ("To Bridge Lake Union"). Even at this early date Denny and his partners anticipated the eventual completion of the Lake Washington Ship Canal, still 27 years in the future. The article also noted that "Mr. D. T. Denny has agreed to grade a fine driveway along the east side of the lake [Union] shore from the ... south end of the lake to the bridge" ("To Bridge Lake Union"). A streetcar line would run along that route all the way from downtown Seattle, then cross the planned bridge into the Brooklyn neighborhood.

Work on the Latona Bridge got underway and was nearing completion by November 1890. One indication of its immediate impact came in late October, when the Lake Union Transfer Company announced that its three passenger steamers, the Latona, City of Latona, and Maud Foster, would be transferred from Lake Union, where they were no longer needed, to Lake Washington, where they still were. How they made the passage remains a bit of a mystery.

The span was virtually complete by late January 1891, at a total cost of $5,000, somewhat below estimates. In May of that year, the Rainier Power & Railway Company, principally owned by David Denny, was granted the franchise to operate the street railway that would use the bridge. A ceremony dedicating the span was held on July 1, 1891, but due to a disputed right-of-way issue, the first streetcar did not cross until July 26.

Denny lost almost everything, including the railway company, during the national financial meltdown known as the Panic of 1893. As will be seen, in 1901 a second Latona Bridge adjacent to the first was built by the Seattle Electric Company, which a year earlier had consolidated all of the city's street railways under the corporate umbrella of the massive East Coast holding company Stone & Webster.

Very few specific details about the original Latona Bridge or its construction have survived. Keyed to modern landmarks, it was located directly under today's Interstate 5 span over the lake, left the south shore near the intersection of today's Fairview Avenue E and Fuhrman Avenue E and ended on the north shore at 6th Avenue NE. There were two wide roadways separated by a narrow gap, all borne by a framework of dozens of closely spaced piers along most of the bridge's length. Somewhat south of the middle was a wide gap in the piers spanned by a truss-type structure of steel beams. The gap permitted small vessels and log booms to pass under the bridge, and the superstructure above (which from an early photograph appears to be of a design known as a Warren truss) was intended to facilitate conversion to a drawbridge should a ship canal be completed.

The area encompassing Fremont, Edgewater, Latona, and Brooklyn (among other neighborhoods) was annexed to Seattle on May 1, 1891, but in some ways remained a place apart for a while longer, even after the bridge was completed. In May 1892 a grocery store near the north end of the Latona Bridge was robbed. The proprietor, Sylvia Paysee, "informed [Seattle] Chief of Police Jackson, who proceeded to inquire where Latona was, where the Latona Bridge crossed the lake and whether the place was within the city limits." In fact, commented The Seattle Times, "he knew little more about it than an utter stranger to the city" ("Latona Notes, May 19, 1892").

The Second Latona Bridge

By 1900 there was consensus that a ship canal was inevitable, and that anything that interfered with future navigability would eventually have to give way to its requirements. This was particularly so for bridges.

By 1901 ownership of the Latona Bridge had passed to the city and ownership of the streetcar line to the Seattle Electric Company. The span was in pretty bad shape, and the company was obligated by its franchise to share equally in the cost of repairing and maintaining it. The city proposed that they together tear down the structure and build a new, multipurpose bridge. In June 1901, the company told the city that it believed the eventual canal would require an expensive drawbridge at Fremont, which would become the primary route for its streetcars. The company saw little sense in also building an expensive multipurpose bridge at Latona that would only have to be removed sometime later.

What Seattle Electric proposed instead was that the first Latona Bridge be used for non-rail traffic (which would soon include automobiles), and that the company build a new trestle next to it for its streetcars, "because the present structure was built for small [rail] cars and it is our intention to run big cars on that line" ("That Latona Bridge"). That it wanted to do even this much was due to a belief that "Ravenna Park will be fixed up and made one of the chief pleasure resorts of the city," thus generating heavy streetcar use ("That Latona Bridge").

On August 1, 1901, The Seattle Times reported, "Yesterday the S. E. Co. [Seattle Electric Company] commenced the construction of its new street railway bridge at Latona. The new bridge is west of the old one and will be a trestle for the sole use of the company. The old bridge will be left for vehicles and foot passengers" ("New Latona Bridge").

The construction apparently went smoothly and the new rail-only bridge opened with little fanfare in 1902. Although there were now actually two separate bridges at Latona, most newspaper accounts referred to them as a single span. For its part, the city allotted funds later that year to rebuild the original Latona Bridge. According to at least one news report, it required near-total replacement, but was done in record time:

"The smartest piece of construction work ever done by a street contractor in this city is conceded to have been accomplished last week by J. A. Bailey on the Latona Bridge. Every bolt and nail and every piece of timber was assembled before a blow was struck.

"Then on Monday morning, October 20, Mr. Bailey began tearing down the old bridge and put in the new. Monday morning, October 27, the new bridge was completed and opened for traffic" ("Built in One Week").

The Latona Bridge served well for several years. In 1909, nearly four million people crossed it, by rail, horse, foot, and car, most of them drawn to the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition on the University of Washington campus. The original bridge was given a new deck and an asphalted surface in 1912 to accommodate increasing numbers of automobiles, but by 1916 it was once again in poor shape. A steel shortage caused by World War I and the pending completion of the Lake Washington Ship Canal dampened support for pouring more money into the aging structure, and the bridge foreman was forced to make a public plea for planking and material to repair the deck and approaches one more time.

Bridges, Open and Closed

Much of the cost of the Lake Washington Ship Canal, including the locks at Ballard, was borne by the federal government, but building the drawbridges that would cross it was the responsibility of the city of Seattle. Bridge-funding proposals had to be put to the voters, and the voters were not always in a generous mood.

The first ballot measure for bridge financing appeared on the ballot on March 3, 1913. The $1.6-million request included not only ship-canal bridges, but also spans over the East and West waterways of the Duwamish River south of downtown. It was defeated by a margin of more than two to one, in large part because it was an all-or-nothing vote and specific details were notably lacking.

It soon became clear that replacement of the Latona Bridge was going to be a harder sell than building new bridges in Ballard and Fremont. In October 1913 the editorial page of The Seattle Times carried a single untitled sentence on the issue: "The Latona Bridge continues largely in the limelight as a most perplexing problem in the spanning of the Lake Washington canal" (The Seattle Times, October 9, 1913, p. 4). The following year, voters were presented proposals for four bridges over the ship canal -- at Ballard, Fremont, 6th Avenue NE, and Montlake -- and could vote them up or down individually. On June 30, 1914, they approved bonds to provide funding for those at Ballard and Fremont, while rejecting those at 6th Avenue NE (site of the Latona Bridge) and Montlake.

Voters would not approve a bridge at Montlake until 1924, but on March 2, 1915, they passed by a narrow margin funding for a new span to replace the Latona Bridge. After prolonged and heated public debate, the proposed route had been changed, and this seems to have been the deciding factor. The new bridge would connect Eastlake Avenue E on the south with 10th Avenue NE on the north, putting it somewhat east of the existing bridge.

Construction of the Fremont and Ballard bridges went full-steam ahead and would be completed before or not long after the formal opening of the canal in 1917. The same was not true of the Latona replacement, first dubbed the "Tenth Avenue Bridge" ("Substructure Not Ready..."). About 18,000 people a day crossed the lake on the spans of the old bridge, and simply tearing it down without a replacement in place seemed out of the question. On the other hand, if the long-sought goal of sizable ships being able to travel from Lake Washington to Elliott Bay were to be realized, both sections of the Latona Bridge would have to open. Neither did.

Awkward Openings

Even before work began on converting the Latona Bridge from fixed spans to draw-spans, both sections had to be temporarily breached to allow a government dredge to reach Montlake for work on the connection to Lake Washington. This was done on November 15, 1916, with traffic rerouted west to the equally doomed Stone Way Bridge, built in 1911 and slated to be torn down upon completion of the bascule bridge at Fremont. Once the dredge was through, the two spans of the Latona Bridge were patched back together to await their fate.

On November 24, 1916, the Seattle Board of Public Works ordered that work on converting both sections of the Latona Bridge to draw-spans should begin immediately, and that they would remain in place until the Tenth Avenue Bridge was completed, a task estimated to take two years. As noted above, the easternmost Latona trestle, built in 1901, had a steel-truss section spanning a gap in the piers, designed to facilitate its conversion to a drawbridge. The idea proved sound, and in rather short order that section of the original bridge was modified to swing horizontally to the east from a pivot point at the gap's south end.

By this time the Seattle Electric Company had been absorbed into an even-larger Stone & Webster conglomerate, the Puget Sound Traction, Light and Power Company. It now had to modify its rail-only portion of the Latona Bridge so it too could open. There is little contemporary record of just how or precisely when that was done, but the job was completed before the formal opening of the ship canal on July 4, 1917. In the very few photos that exist, the streetcar tracks leading to the bridge from the north can be seen to curve to the west and onto the new trestle, which wends a somewhat serpentine way across the water to the other shore.

For reasons that are unclear, but probably had to do with the original configuration of its trestle, the power company elected to have its movable section open vertically, rather than horizontally as the city had done. A series of cables and pulleys were threaded through a tall framework adjacent to the movable section's south end, attached to the north end, then used to pull it into a near-vertical position.

When both draw-span sections were completed and opened for the first time, they presented a rather unusual sight, somewhat resembling a semaphore signaler flagging the letter "P," with one arm thrust skyward and the other flung out to the side. It was neither pretty nor easy to operate, but it worked. The canal opened on time, and the Latona Bridge stayed in awkward operation until its successor, the University Bridge, was dedicated on June 30, 1919. A month and a half later, on August 15, the city ordered "the immediate removal of the street car and vehicles bridges now paralleling the new bridge across Lake Union" ("Latona Bridge Soon to Be Past..."). Two weeks later barely a trace remained.

The University Bridge

The construction of the Latona Bridge's replacement seemed, on the surface, a rather simpler affair, particularly because city engineers had gained valuable experience building similar double-leaf bascule bridges at Ballard and Fremont. Once the plans and specifications were complete, the Beers Construction Company won the contract to build both the steel superstructure and concrete substructure of the new span with a bid of $302,979.75. Construction was to start by May 1, 1916, and to be completed within 15 months.

By August that year Beers had defaulted on both the substructure and superstructure work, and virtually no progress had been made. A primary cause was the soil at the south end of the bridge, which was found to have the approximate consistency of quicksand. The northern foundation would rest on solid ground, but on the south pilings would have to be driven deep into the sandy soil until a solid, clay layer was reached.

A Do-Over

All the steel for the bridge's superstructure was ready by November 1916, but there was nothing to attach it to. In January 1917 Seattle City Engineer A. H. Dimock (d. 1929) called upon the board of public works to solicit new bids for the bridge, even as the city haggled with Beers's bonding company over the default. Booker, Kiehl & Whipple of Seattle was given the contract to complete the bridge's south foundation, a job that would not be completed until 1918. In the end, 676 piles were driven to depths of 40 to 65 feet below the level of the lake bed before work could proceed on the concrete foundation.

The United States Steel Products Company was the winning bidder for the erection of the bridge's superstructure. Perhaps the only bright side was that during the delays the price of steel had soared, but the city earlier had purchased almost all the needed steel at lower prices.

Judging by the absence of bad news in the local press, it seems that progress on the bridge proceeded without major complications after the south foundation was in place. Or the absence of news may have been due to a belief that by 1918 the public was thoroughly sated with bridges, having been bombarded with dozens if not hundreds of stories about the new ones at Ballard and Fremont and the old ones at Stone Way and Latona. For whatever reason, the work on the Tenth Avenue Bridge, formally renamed the University Bridge in early June 1919, went almost undocumented by local newspapers right up until its completion.

Done at Last

Finally, on June 29, 1919, The Seattle Times announced in large type: "University Bridge to Be Opened Monday" ("University Bridge to Be Opened..."). The paper could barely contain itself:

"Cutting the threads that have bound the giant of development, the great 'jack knife' of the University Bridge, which crosses Lake Union at Eastlake and 10th Avenue Northeast, will swing open on the evening of July 1. Again the knife blades will close and from the Eastlake side toward the University district will pass a parade of pedestrians, automobiles and street cars, the first to cross the bridge, symbolic of the traffic that the bridge is destined to carry" ("University Bridge to Be Opened...").

Public sentiment may have been one of relief more than joy. The dedication ceremony was July 1, 1919. If the original contract with Beers had been adhered to, the University Bridge should have been completed by September 1917. The problems encountered and Beers's default had delayed progress by almost two years, and the final cost of the bridge, $825,275, was more than twice what either the Ballard or Fremont bridges had cost. (Note: The Seattle Times pegged the cost at $747,000 in its June 29, 1919, edition but later, more detailed accountings arrived at the larger figure.) Although money had been saved by the early purchase of steel, the massive, unanticipated work on the south foundation and the reletting of major portions of the contract at wartime prices drove up the cost.

The Times went on to provide a concise, non-technical description of what four years and more than $800,000 had wrought:

"The bridge is described as the double leaf bascule type. It is fifty-two feet above the water, high enough for ordinary traffic to pass without opening the draw. The roadway is forty feet wide, the distance between the piers is 360 feet, and the bascules are 180 feet long. When the bridge is open there is a clear channel 175 feet wide. The length of the bridge from the beginning of the approaches is approximately a half-mile. The bridge itself is of steel on concrete piers. The approaches are built on piles but will be replaced later with permanent material" ("University Bridge to Be Opened...").

The article did not point out that the bridge also had a mechanism by which it could be raised and lowered by hand if the electrical motors malfunctioned, an interesting fact perhaps omitted because it was estimated that doing so would take at least six hours.

A Depression-Era Rebuild

In 1931, in the depths of the Great Depression, Seattle voters approved a $675,000 bond issue to rebuild the University Bridge, which had become grossly inadequate for the volume of traffic it had to bear. By April 1932 a temporary, wood-trestle drawbridge was near completion immediately adjacent to the bridge on the east, which may have given those with long memories an eerie sense of Latona Bridge deja vu. It was designed to carry pedestrians, streetcars, and a few automobiles, but most drivers were expected to use the bridges at Fremont and Montlake until the work was completed. The permanent bridge was closed to traffic in May that year.

The General Construction Company contracted to build the temporary trestle and replace the old wooden approaches to the bridge with wider ones of concrete and steel, at a cost of $446,475. Puget Sound Bridge and Dredging had a separate contract in a lesser amount to widen the main bascule leaves of the bridge to accommodate two additional lanes of traffic, and to add cantilevered extensions along its length on both sides for pedestrians.

Because of the weight of two additional traffic lanes, the University Bridge's wooden decking was replaced with a steel, open-mesh grating. This was the first use of this technology in the United States and was a tremendous improvement. It made the leaves lighter and easier to raise and lower, reduced wind pressure on the structure, and provided a less-slippery surface for automobile traffic.

On April 6, 1933, the day the new bridge was dedicated, President Franklin D. Roosevelt (1882-1945) pressed a button in his office at the White House. It is not clear if the button was actually connected to anything, much less did anything, but it at least symbolically marked the opening of the bridge and was the cue for celebrations to begin. These included a review of the history of the Latona and University bridges by professor and historian Edmond Meany (1862-1935), who had been master of ceremonies for the bridge's 1919 opening celebration.

The streetcar tracks over the bridge were eventually replaced by overhead trolley wires, but the steel decking installed in 1933 lasted until 1990. A computer-aided system for operating the bridge was installed in the early 1980s and upgraded in 2014. The third of Seattle's four ship-canal bascule bridges, the University Bridge, despite a rather difficult beginning, has served its city well, and has been listed on the National Register of Historic Places since 1982.