The Lake Washington Ship Canal's opening was celebrated on July 4, 1917, exactly 63 years after Seattle pioneer Thomas Mercer (1813-1898) first proposed the idea of connecting the saltwater of Puget Sound to the freshwater of Lake Washington via Lake Union. For five decades following Mercer's suggestion, local citizens, business leaders, government officials, military officers, and entrepreneurs discussed where to build the connection and how to pay for it. Finally, after Hiram M. Chittenden (1858-1917) took charge of the Seattle District of the Army Corps of Engineers in 1906, plans were made and federal funding obtained. The ship canal Chittenden designed consisted of two cuts, the Fremont Cut between Salmon Bay and Lake Union and the Montlake Cut between Lake Union and Lake Washington, and a set of locks at the west end of Salmon Bay. The canal's construction lowered the water level of Lake Washington by nine feet and raised that of Salmon Bay behind the locks, changing it from a tidal inlet to a freshwater reservoir.

Water Routes

People have been moving between the interior lakes and saltwater of the Seattle area for thousands of years. The earliest definitive evidence so far located of humans in the region comes from a site along Bear Creek in Redmond. Archaeologists radiocarbon dated that site to about 12,000 years ago. Other sites at the Sammamish River, Marymoor Park, Salmon Bay, and the Magnolia peninsula show that people have lived in the area more or less continuously since then.

Although archaeologists lack specific evidence of how these people traveled, they most likely used waterways to avoid the forests and hills that made overland travel in the region challenging. Among other routes, they would have floated down or walked along the Sammamish River to Lake Washington and continued out to Puget Sound via Lake Union (a small freshwater lake midway between the Sound and the larger lake) and Salmon Bay (a narrow saltwater inlet extending eastward from Shilshole Bay between the Magnolia peninsula and what is now the Ballard neighborhood), thus starting the long tradition of using this route as a central means of linking freshwater and saltwater.

In historic times, Lake Washington continued to be a central resource for Native people across the region. Closest to the lake, the Duwamish lived along its shores or reached it by trail or boat. East of the lake were the Snoqualmie, who traveled down from Lake Sammamish, and to the west were the Suquamish, who came over from their winter villages on the Kitsap Peninsula. All were seeking resources such as food and clothing.

Thomas Mercer was the first non-Native settler to recognize the potential of the route via Lake Union. At a July 4, 1854, picnic, he suggested the name "Union" for the lake a short distance north of the new settlement of Seattle on Elliott Bay, noting the possibility "of this little body of water sometime providing a connecting link uniting the larger lake and Puget Sound" (Bagley, 371).

As the Native travelers illustrated, connecting saltwater and freshwater made sense, except for one large problem. Lake Washington was about 29 feet, and Lake Union about 20 feet, above sea level, while Salmon Bay was a tidal inlet with a water level that fluctuated 10 to 12 feet daily. Uniting the bodies of water would require locks -- either one or two -- to raise or lower boats from one level to another, or lowering one or both lakes. Solving this question would be central to the decades-long debate following Mercer's speech.

First Attempts

Young Harvey Lake Pike (ca. 1842-1897) was the first to take up Mercer's idea. Pike's family arrived in Seattle in 1858. His father worked as carpenter, and Harvey as a painter, for the University of Washington. Pike Street in downtown Seattle honors the family.

In June 1861 Harvey Pike bartered land-clearing labor for some 162 acres between Lake Union and Lake Washington in what is now Seattle's Montlake neighborhood. At some point he began to cut a channel from one lake to the other using a pick, shovel, and wheelbarrow. No source identifies when Pike began work but it was probably sometime between when he acquired the land and June 24, 1869, when he filed the Plat of Union City on land now crossed by State Route (SR) 520. On the plat, Pike reserved space for a 200-foot-wide canal. Pike also helped form the Lake Washington Canal Company, which professed the goal of connecting Puget Sound to Lake Washington but made no actual attempt to build a canal.

However, others were now considering the idea. In 1867, Brigadier General Barton S. Alexander (1819-1878), senior military engineer for the Army Corps of Engineers on the Pacific coast, organized a coastal defense survey. Alexander concluded that Lake Washington had the potential as a port if a canal connected it to Puget Sound.

In December 1871 Alexander released a survey made by engineer Lieutenant Thomas H. Handbury (1841-1915). Handbury favored the shortest route possible. Known as the Mercer's Farm route, it extended from Lake Union directly to Elliott Bay. Handbury's second potential route followed the path of the Seattle Coal & Transportation Company's tramway, which ran from a coal bunker at the base of Pike Street east to about modern-day Westlake Avenue and then north to Lake Union.

Despite the Mercer's Farm route requiring a 119-foot-deep cut, Alexander prioritized it over connecting Lake Union and Shilshole Bay via Salmon Bay because a canal there required too much dredging and would suffer from exposure to "the cannonade of an enemy in time of war" ("Report No. 494," p. 6). He also rejected a route that followed the Black River, then the outlet of Lake Washington, located at the lake's southern end, and the Duwamish River to Elliott Bay. Ultimately, Alexander concluded that although the Puget Sound region offered one of only three places on the West Coast to build a secure port for the U.S. Navy, the area possessed too few people and resources to justify further study.

Portage Canal Connects the Lakes

Another decade passed before serious consideration of a canal resurfaced. In March 1883, a group of investors led by Thomas Burke (1849-1925), David Denny (1832-1903), Guy Phinney (1851-1893), and Benjamin F. Day (1837-1904) formed the Lake Washington Improvement Company. All four owned land around Lake Union, then starting to become a manufacturing center.

By that June the Improvement Company had contracted with J. J. Cummings and Co. to dig the needed cuts. The contractor would employ 100 men and many teams of horses. Reflecting growing racism among some in Seattle, Cummings promised he would not hire any Chinese laborers.

By July Cummings's men had removed 14,000 cubic yards of material for a canal connecting the two lakes where SR 520 would later be built. But then his crews ran into a hard layer of sediment. When Cummings asked for more money than he had initially bid for sediment removal, the Improvement Company refused. In October, it abrogated his contract and hired Chinese workers through the contracting firm Wa Chong Company.

What the Wa Chong Company's men did and when is not clear. All information that exists comes from later sources. The crews finished digging sometime in 1885 (they had to have been done by February 1886, when Seattle mobs forced nearly all Chinese residents out of town). Contemporary accounts describe their work on the Fremont Cut between Salmon Bay and Lake Union, but there is no firsthand evidence for their work at Montlake, though they presumably finished the job Cummings began.

The completed connection between the lakes, known as the Portage Canal, was wide enough for logs and small vessels. A 1903 army report noted that the canal was 16 feet wide with two 51-foot-long locks, at the Lake Union end of the canal, to lift small boats and steamers up to the larger lake.

Possible Routes

After a two-decade hiatus, the federal government decided to reinvestigate canal options and provided $10,000 for a three-member board of engineers -- Colonel George H. Mendell (1831-1902), Captain Thomas W. Symons (1849-1920), and now-Major Thomas H. Handbury -- to study a canal "to connect Lakes Union, Samamish [sic], and Washington with Puget Sound" ("Canal Connecting ...").

Their 1891 report dismissed a canal from Lake Sammamish to Lake Washington and focused on five possible routes to connect Lake Washington to Puget Sound. The first followed the natural link of the Black and Duwamish Rivers. The second and third were Alexander's tramway and Mercer's Farm routes from Elliott Bay directly to Lake Union. The final two routes utilized Salmon Bay, one using Salmon Bay's existing outlet to Shilshole Bay and the other a cut from Smith Cove through today's Interbay. The board rejected the Duwamish route because of its great cost and eliminated Alexander's routes because the former wilderness between downtown and Lake Union had been built up with businesses, raising the price of procuring the right-of-way.

Of the remaining two routes, the engineers preferred going through Smith Cove because its entrance was closer to the main Seattle harbor and "less exposed to bombardment by an enemy's fleet" ("Canal Connecting ..."). It was, however, more expensive, $3.5 million compared to $2.9 million for the Shilshole route. For either route, they proposed keeping both Lake Union and Lake Washington at existing levels, with one set of locks to raise and lower boats between Puget Sound and Salmon Bay and another at Montlake to do so between the two lakes.

The South Canal

With the federal survey completed, the means to create a canal seemed imminent, or so Seattleites thought. However, Congress decided not to provide additional funding for a canal in the 1892 River and Harbor Act. But another canal proposal was already in the works. This one would not connect through Lake Union. Instead it would be south of downtown Seattle and link Elliott Bay directly to Lake Washington via a deep chasm dug through the high ridge of Beacon Hill.

Former territorial governor Eugene Semple (1840-1908) was the main driver of this "South Canal." In addition to cutting a canal, Semple planned to fill the tideflats of the Duwamish River, which for half the day were open mud and the other half 10 to 15 feet deep in water. The tideflats stretched from Beacon Hill to West Seattle and south to where the Spokane Street overpass is now located.

Semple incorporated the Seattle and Lake Washington Waterway Company (SLWWC) on June 25, 1894. The new company began to raise private funds in part by tapping into the Mississippi Valley Trust Company of St. Louis, which had connections to Semple's wealthy nephews. Also seeking financial support from Seattleites, the SLWWC held a public meeting on March 28, 1895. With speeches from the mayor and other prominent citizens, Semple's company raised the first $100,300 on the spot from the 3,500 attendees. By May 10, $545,000 had been pledged.

Work began on July 29, 1895, when Semple's daughter Zoe set the machinery on the dredger Anaconda in motion with the lift of a lever, which started a pump that sucked mud from the tideflats. The mud flowed through a pipe and was expelled behind a permeable barrier just west of where Safeco Field now stands. Despite various legal challenges, the SLWWC pumped millions of cubic yards of sediment, creating 333 acres of new land in the tideflats by September 1904.

Semple did not forget his South Canal. In November 1901, soon after completion of Seattle's first Cedar River pipeline provided an ample water supply, crews began cutting into the base of Beacon Hill. Their main tool was the hydraulic giant -- technology used in the California gold rush -- which used water to eat away the soft glacial sediments. Each day 14 million gallons of water flowed from atop Beacon Hill down through successively smaller pipes until it shot out of a nozzle with the force of cannon.

Not everyone supported Semple's plan. In particular, those who wanted a northern canal via Lake Union rallied public opinion and in June 1904 convinced the Seattle City Council to cut off Semple's supply of water. This was the end of the South Canal scheme, although the SLWWC continued filling tidelands, creating about 1,400 acres of new land by 1917.

Chittenden Takes Charge

But north-canal supporters were not doing that well either. In 1906, fearing Congress might not fully fund the canal in the near future, the Chamber of Commerce endorsed a new plan. James A. Moore (1861-1929), who built residential neighborhoods, the Moore Theater, and several downtown office buildings during his career, had a group of East Coast investors interested in building a steel plant on Lake Washington. They would need access to Puget Sound, so Moore proposed that King County pay him $500,000 to construct a timber lock and dredge the channel.

Congress granted Moore permission in June 1906, the King County Commissioners approved the plan in August, voters authorized issuance of bonds in September, and preparations for construction began -- but Moore did not get to build the canal. In April 1906, Hiram Chittenden replaced Francis A. Pope (1875-1953) as the head of the Seattle District of the Army Corps and began to study the canal situation at the request of the Chief of Engineers, General Alexander Mackenzie (1844-1921). Chittenden was concerned that the timber lock Moore proposed would be insufficient and the government would inherit an inadequate facility.

Chittenden filed his report on December 6, 1907. He explained the need for a masonry lock at the mouth of Salmon Bay, sometimes known as the Narrows, and recommended construction of two locks there -- one for smaller vessels and one for larger ships with a second set of gates to accommodate midsize vessels without having to fill the entire large lock. As a cost-saving measure, Chittenden omitted the lock at Montlake that the 1891 report had proposed, which meant Lake Washington would be lowered to the level of Lake Union.

Chittenden's plan for the Seattle locks faced two hurdles before construction could begin: location and funding. Ballard mill owners had long favored locating locks at the eastern head of Salmon Bay (the outlet of the Fremont Cut) rather than at the Narrows on the bay's western side, because the water level of Salmon Bay behind the locks would rise substantially and force the mills to move and/or raise their docks. The Chamber of Commerce threw its support behind the more easterly lock location, which Chittenden briefly agreed to as well, though his biographer suggests he only did so with the idea of getting consensus and moving the project forward.

Chittenden quickly retreated to his original preference, locating the locks at the Narrows. He also began to rally support by holding public meetings and writing articles for local newspapers. Poor health led him to retire from the Corps of Engineers in 1908 but he continued to aid the locks effort. Finally, in 1910, the U.S. Congress passed a River and Harbor Act that included a $2,275,000 appropriation for Seattle's ship canal. This allowed the project to proceed along the lines proposed by Chittenden.

Work Begins

Work on the project had actually begun in 1909, with excavation of a canal at Montlake. Funding for this part of the project came from the state and county. The plan was to replace the narrow channel that Chinese laborers had cut in 1885 with a new canal farther north, where today's Montlake Cut is. Contractor C. J. Erickson (1852-1937) began on October 27 and finished in the summer of 1910. Erickson's cut was smaller and shallower than the modern canal.

Recognizing the need for a bigger canal, in June 1912 the Corps of Engineers hired Stillwell Brothers Construction Company to excavate a larger cut, 2,200 feet long, 100 feet wide at the bottom, and 36 feet deep. Stillwell finished in late 1913 and on December 31, 1913, blasted out the cofferdam (or temporary dam) on the west end of the canal. Water gushed into the cut and soon rose to the level of Lake Union, 20 feet above sea level but 9 feet below Lake Washington. Unfortunately, the south side of the cut was slumping, an issue that had plagued the project throughout construction but that engineers hoped would stop when water entered the cut. Stillwell built another cofferdam, drained the canal, and poured concrete on the slide area. Workers blasted that cofferdam in November 1914. But slumping continued, leading to another cofferdam in March 1916 and additional concrete work.

Work on the locks themselves began in August 1911. The first task was building a cofferdam around the site of the locks, on the north side of Salmon Bay in Ballard. It was completed a year later and ran for about 2,300 feet in a large curve. South of the dam was a temporary channel dredged to allow water and boats to move in and out of Salmon Bay during construction.

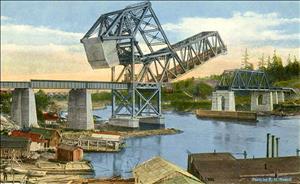

Building the Locks

Crews dredged 245,000 cubic yards of sediment to create a lock pit, then pumped the water out and began building a 65-foot-high wooden trestle down the center of the pit to support a supply train used throughout the project. Also built were two gantry cranes to travel overhead. Rising 75 feet above the trestle, the steel gantries spanned the entire workspace; each held two movable cars, or trolleys, able to transport five tons of supplies apiece. With the gantries, crews could easily move heavy loads, particularly concrete, to any point in the construction site.

Concrete pouring for the locks structure began in February 1913 and by November 1914 most of it was complete. The walls were not built completely solid -- two culverts run the length of each of the locks. These conduits facilitate the filling of the lock chambers; water enters at the upper, Salmon Bay, end of the culvert and flows into the locks via drains on each side of the chamber.

Before the concrete work was completed, workers began to install the lock gates. The locks required nine gates, three sets operating in the large lock and two in the smaller lock plus one set of guard gates at each end of each of the locks. These would be used when the lock chambers needed to be emptied and cleaned or repaired. The gates are known as mitering gates, because the doors, or leaves, meet at an angle facing upstream and resemble a miter joint. Each leaf is hollow and consists of a series of stacked layers of steel framing surrounded by a waterproof skin, also of steel. The tallest doors are 55 feet high and weigh 480,000 pounds. About 4.4 million pounds of steel went into gate construction.

With the gates in place and concrete work completed, workers could turn to the next stage of the project: connecting freshwater and saltwater. James B. Cavanaugh (1869-1927) of the Army Corps started the process on a cold February 2, 1916, by allowing water to flow into the larger lock. The first boat to go through was the Orcas, a tender operated by the corps.

With the locks open, workers began to build a new cofferdam south of the locks in the temporary channel that had been excavated between Salmon Bay and Shilshole Bay. The cofferdam enclosed the area where the overflow, or spillway dam, was to be built. The spillway dam was 235 feet wide with six gates, known as Tainter gates, each resembling a piece of pie with the round end facing upstream. The gates, operated independently, were a standard design still used on waterways across the country.

The main job of the dam was to allow excess water to flow out of Salmon Bay, to help keep it, Lake Union, and Lake Washington all at an elevation of 20 to 22 feet above sea level. Workers completed the spillway in a little more than three months. The lock gates remained open during work on the spillway.

Connection Completed

Then, with the spillway dam in place, on July 12, 1916, at 6 a.m., the gates of the locks closed, and Salmon Bay ceased to be a tidal inlet and started to become a freshwater reservoir. Almost three weeks later, Salmon Bay was filled with enough water from Lake Union to allow boats to lock through. Again, the first boat to do so was the Orcas, which locked through the smaller lock on July 25. The official opening occurred at 10 a.m. on August 3, when the snag steamer Swinomish, accompanied by the Orcas, traveled through the larger lock.

On Friday, August 25, 1916, with the armoring of the Montlake Cut's walls complete, the Corps of Engineers began the long-awaited "union of the waters" of Lake Union and Lake Washington ("Waters of Lakes United ..."). At 2 p.m., workmen with shovels opened up a small cut in the third and final cofferdam at the west end of the Montlake Cut. The stream of water pouring into the cut from Lake Union quickly turned into a raging torrent, causing crowds on the cofferdam to flee the water, dirt, and huge timbers of the rapidly disintegrating dam.

Three days later, after crews had cleaned out the debris in the cut, the corps opened gates at the east end and began to lower Lake Washington. The plan was to let the water out slowly in order to not damage houseboats around the lakes, the Fremont Cut, or the locks. Lake Washington dropped two feet in the first week and four feet in the first month. After that it dropped up to two inches a day. As the water level dropped, it fell below the lake's drainage outlet to the Black River, and the river eventually dried up. The ship canal became the lake's new outlet.

By late October, Lake Washington had lowered a full nine feet and was equal in elevation to Lake Union and Salmon Bay, but boats were not immediately allowed to pass through the Montlake Cut. Crews still had to remove the gates that separated Union Bay on Lake Washington from the canal, as well as sediment and debris that had accumulated at either end of the cut. This was soon completed, and small boats finally began to move freely between Lake Union and Lake Washington.

Vessels small and large did not wait for 1917's big grand-opening celebration to use the locks and new freshwater harbor of Salmon Bay behind them. By early November, The Seattle Times reported that much of the Puget Sound fishing and whaling fleet was mooring for the winter at the Salmon Bay terminal soon named Fishermen's Terminal, adding that more than 5,000 vessels had passed through the locks since they opened to boat traffic in July.

When the grand-opening celebration for the Lake Washington Ship Canal and Government Locks was finally held on July 4, 1917, 63 years to the day after Thomas Mercer suggested the connection, the P-I reported that more than half the city's population lined the shores. The great day consisted of the SS Roosevelt locking through to Salmon Bay, stopping for series of speeches, then leading a parade of more than 200 boats through the cuts and Lake Union into Lake Washington.

The Times proclaimed: "[H]ere, completed, ready for use, actually in use, [is] a thing that will do more toward bringing Seattle its destined million inhabitants and undisputed Pacific Coast supremacy than any other factor the city has ever known or is likely to know in the present generation" ("Seattle's Ship Way ...").

The city of Seattle itself hasn't reached "its destined million inhabitants," but by the canal's centennial year the larger Seattle metropolitan area was nearing 4 million (and growing fast). The Lake Washington Ship Canal and the development it made possible in Lake Union and Lake Washington played a significant part in that growth.

Hiram Chittenden did not live to see the impact of the canal whose realization he spearheaded. He died in October 1917, just months after the grand opening. In 1956, the locks were officially renamed the Hiram M. Chittenden Locks in his honor, though they are commonly called the Ballard Locks.