On June 11, 1906, President Theodore Roosevelt (1859-1919) signs an act, passed unanimously by Congress, that grants Seattle developer James Alexander Moore (1861-1929) authorization to build a canal along the federal government right of away connecting Puget Sound with Lake Washington via Lake Union. Moore grew up in Nova Scotia, Canada, and since 1897 has invested in real estate in Seattle. King County commissioners and voters will approve half a million dollars in government bonds payable to Moore to build the canal, but Moore will give up his plan and turn over the canal right-of-way less than a year later, following a state supreme court decision invalidating the bond issue. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers will ultimately build the Lake Washington Ship Canal, which will celebrate its grand opening 11 years after Moore's federal authorization.

History of Plans for a Ship Canal

The history of plans for a ship canal between Puget Sound and Lake Washington is as old as the city of Seattle. Captain George Brinton McLellan (1826-1885), nicknamed "Young Napoleon" or "Little Mac" and later a Union Army general in the Civil War, became part of a myth associated with the canal's origins. McClellan, who arrived in Seattle in 1853, has been credited as the first person to recommend the idea of a canal. However, while he evidently camped on Lake Union, which ultimately became a key link in the canal, he did not propose a canal and instead focused on the quality of the harbor at Elliott Bay. In a report to Governor Isaac Ingalls Stevens (1818-1862) in January 1854, McClellan wrote about returning from a trip to Snoqualmie Prairie and went on to praise Seattle's harbor:

"On the 15th (January), camped on a small lake which connects with the salt water, about five miles to the north of Seattle. On the 16th reached Seattle; the floating ice gave us much trouble, on the morning of the 17th abandoned the idea of going to the D'Wamish, the ice being so thick and abundant as to close the passage ... that of Seattle is by far, the best, being well protected against the wind, having thirty fathoms of water, a most excellent holding ground, being easily approached from the Straits of Fuca, and having a good back country. It is therefore my opinion, the proper terminus for any railroad extending the waters commonly now as Puget Sound" (Bagley, 386).

Later the same year, on July 4, 1854, at a picnic on Lake Union, Seattle pioneer Thomas Mercer (1813-1898) did propose the concept of a route connecting the fresh waters of Lake Washington and Lake Union to the salt waters of Puget Sound by way of a canal. "It is not clear why Mercer made his proposal"(Williams and Ott, 36), but the idea first raised in 1854 eventually launched a series of attempts and verbal battles over many years by various citizens supporting different ideas on whether and how to connect Seattle's saltwater harbor to its freshwater lakes, discussions and debates that ultimately extended from the state of Washington all the way to Washington, D.C.

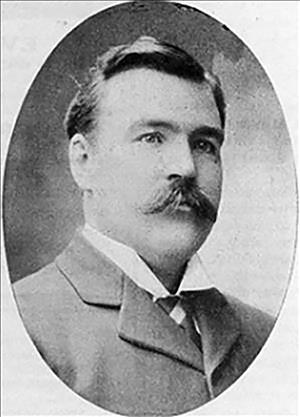

James Alexander Moore

James Alexander Moore was born in Nova Scotia, Canada, on October 23, 1861, to Andrew K. (1827-1900) and Isabel McClellan (1829-1893) Moore. The Moore family, deeply religious Presbyterians and Congregationalists of Scotch-Irish ancestry, had been living in Nova Scotia since the seventeenth century and was prominent in the ship-building industry. James Moore grew up in Nova Scotia as the only brother among five sisters. After graduating from public school, he began working with his father in the shipping business. Moore immigrated to the United States in 1880 at the age of 19, leaving the family business. He first made his way to Pomery, Iowa, then moved on to Denver, Colorado, where he married Eugenia G. "Bessie" Jones (1867-1908) on December 16, 1885. The couple would have four children, two of whom died very young. Moore arrived in Seattle in 1886 or 1887, and in 1888 he became a naturalized U.S. citizen.

Armed with ambition, vision, and a flamboyant personality, Moore opened a real-estate business, the Moore Investment Company, in 1897. From offices located downtown at 112 Columbia Street, Moore's firm focused on Seattle properties. With the launch of his new business, architectural assistance from William D. Kimbal (1855-1907), and contacts to raise money and purchase land in Seattle, Moore platted many tracts, developing numerous areas in such neighborhoods as Madison Park, Rainier Beach, Latona, Brooklyn (later the University District), Renton Hills, and Capitol Hill. In 1901, he platted Capitol Hill on a huge scale. During his career, Moore would go on to develop more neighborhoods, and build the Moore Theatre, the Washington Hotel, his own home on 14th Avenue E on Capitol Hill, and several other buildings in Seattle's downtown, along the way making a large fortune for himself.

Moore's Canal Plan

In April 1906, James A. Moore, in a succession of several meetings with a Seattle Chamber of Commerce committee consisting of Judge Thomas Burke (1849-1925), John Harte McGraw (1850-1910), and Fredrick Crane Harper (1855-1936), proposed a new plan to build a canal connecting the waters of Puget Sound and Lake Washington. (Over the past half century, attempts at a canal had been made by a variety of people, including Burke, and a narrow channel suitable for logs and small boats had been dredged between Lake Washington and Lake Union, but there was still nothing resembling a ship canal to saltwater.) Moore discussed his new plan carefully, emphasizing the advantages of building a steel plant in Kirkland on Lake Washington and noting that doing so was dependent on constructing a canal that would provide transportation for raw materials and finished products. Two other sites for the plant were being considered if it was not possible to build the canal.

The Seattle Chamber of Commerce rallied behind the plan Moore proposed and numerous ideas were suggested to secure construction right away. Moore promised to build a canal with wooden locks (single timber locks), 600 feet long and 75 feet wide, at the head of Salmon Bay, to raise ships to the level of Lake Union; the level of Lake Washington would be lowered to that of Lake Union. In return, Moore would receive payment of $500,000, and the canal right-of-way. Construction of the canal and locks would not begin until after plans and specifications were submitted to the Secretary of War for his approval. Moore would operate for three years and then turn the canal over to the federal government. The end result of the many discussions was to approach the government with the new canal plan.

At the same time as Moore was presenting his plan, however, Hiram Martin Chittenden (1858-1917) arrived in April 1906 to take charge of the Seattle District of the Army Corps of Engineers, which had been involved in surveying and considering various potential canal routes since the 1860s. Chittenden came to Seattle with extensive experience working on important projects such as the road system for Yellowstone National Park and flood control projects in the Ohio River Basin and along the Sacramento River in California. The Corps' Chief of Engineers, General Alexander A. Mackenzie (1844-1921), asked Chittenden to review Moore's canal plan and provide his opinion. Chittenden was not pleased with the plan at all:

"The lock in the Moore plan, he contended, was much too narrow for the traffic it would have to bear and for the flowage of water from Lake Washington into the canal. Above all the construction of a timber lock was foolish because it would probably last only five years before deterioration. The United States thus would be presented with a canal with a weak lock that soon would require replacement at great expense. Finally, the promoter had grossly underestimated the costs of the project, which would be twice the $500,000 Moore expected to expend, a financial miscalculation" (Dodds, 132).

Chittenden recommended postponing federal approval of the plan until the next session of Congress so that it could be presented and considered in more detail. Mackenzie followed this advice and tried to postpone congressional consideration of the plan, but his efforts to do so failed.

Federal Authorities Approve

In May 1906, the Seattle Chamber of Commerce sent John H. McGraw and Moore to Washington, D.C., to appear before a congressional committee on behalf of King County, lobbying to obtain the federal right-of-way and to get permission to build the canal. On June 1, 1906, Wesley L. Jones (1863-1932), one of the state's U.S. representatives, submitted a report to Congress in support of Moore's request to construct a canal connecting Lake Washington with Puget Sound.

On June 11, 1906, after both branches of Congress approved Moore's plan unanimously, President Theodore Roosevelt signed the legislation. Even before the president gave the necessary final approval, Moore and McGraw headed home with the confidence they needed to move forward and begin preparing to build the canal. When he reached Seattle on June 12, Moore told The Seattle Star:

"We had little difficulty in convincing the federal authorities of the advisability of granting our request. Before I left Washington, I was quite sure that the President would sign the bill, as he did yesterday"("Canal Work Only Awaits Bond Issue").

The business community hailed the approval as a victory. The next step was for the King County commissioners to call, as early as possible, a special election for voters to approve the the issuance of $500,000 in public bonds to fund the project, with the money from the bonds to be paid to Moore for constructing the canal. Controversy over the plan began to increase. Before authorizing an election to approve the issuance of public bonds, P. J. Smith, the chairman of Board of County Commissioners, wanted Moore to give King County a bond insuring payment of any damages caused by construction of the canal that the county might be held liable for. The commissioners argued it would be impossible to sell the construction bonds unless the county was protected from any liability. Moore pushed back and refused to give a bond to protect King County against liability for any damages. This dispute went on for several weeks between Moore and the commissioners, threatening the entire project.

King County Commissioners and Voters Approve

A Seattle Chamber of Commerce committee consisting of McGraw, Burke, and Richard Achilles Ballinger (1858-1922) met to discuss the status of the canal question due to the liability concerns. The committee collectively decided to see King County Prosecuting Attorney Kenneth Mackintosh (1875-1957) for the sole purpose of convincing Smith to change his opinion and support passage of a resolution calling for an election to approve the bond issue, with a provision that any damages the county had to pay would be deducted from the $500,000 due to Moore upon completion of the canal. On August 6, 1906, the committee asked Mackintosh to write a letter to the commissioners expressing his opinion of the proposed resolution. Mackintosh wrote:

"As this office has already advised you we deem it essential that the Board of County Commissioners should protect King County against the contingency of any damages being recovered against it by the reason of the construction of this canal. It was first suggested that a bond be taken from Mr. Moore who is to construct the canal to thus secure the country. This Mr. Moore refused to do. The resolution now under consideration provided that the county may be protected in a way other than by bond, namely: by putting the $500,000 bond issue in escrow to be delivered to Mr. Moore upon the completion of the canal, in the event that no damages have been recovered against the county by reason of such construction. In other words, the amount of damages recovered against the county, if any such are recovered, may be deducted from the amount of the $500,000 bond issue before the same is delivered to Mr. Moore. This plan not only amply protects the county but is probably more satisfactory than the giving of a bond by Mr. Moore, as it places the bonds absolutely in the control of the County Commissioners and they may withhold payment of these bonds up to an amount sufficient to cover any judgments that may be obtained against the county, thus obviating the necessity of a suit. I would therefore advise you that in my opinion this resolution if adopted would amply protect the county and it also gives the citizens of the county an early opportunity to express their opinion as to the advisability of issuing $500,000 in bonds to insure the completion of this canal" (Mackintosh to Commissioners).

With considerable hesitation and concern, the Board of County Commissioners -- Smith, Charles Baker, and Dan R. Abraham (1856-1943) -- approved the resolution on August 10, 1906. Now more than ever support for the canal in Seattle and throughout King County was at an all-time high, with supporters arguing that construction of a canal would be the region's greatest commercial and maritime achievement, and warning that failing to proceed would foreclose hope of a canal for many years. A special election was held on Wednesday, September 12, 1906, and voters approved the bond issue overwhelmingly, with 13,095 votes in favor and only 2,694 opposed. Planning for construction of the canal began immediately.

Washington State Supreme Court Disapproves

The popularity of the canal did not discourage either Chittenden or the county commissioners from expressing concerns about Moore's canal plan to community leaders. Chittenden filed a report in December 1906 strongly recommending changes to Moore's canal plan. Moore began to lose local support even as a lawsuit challenging the constitutionality of the $500,000 bond issue made its way through the courts. Local taxpayers opposed to the bond funding argued that the state constitutional prohibition on giving or loaning public funds to private individuals invalidated the bonds, since they were to be paid to Moore. Mackintosh, defending the county's right to issue the bonds, asserted that they were valid because the canal whose construction they funded would ultimately go to the federal government, not a private individual. In November 1906, a King County Superior Court judge dismissed the lawsuit, but the taxpayers appealed.

On March 1, 1907, the Washington State Supreme Court declared that the canal bond issue was invalid, holding that even if the bonds ultimately benefited the federal government rather than a private individual, the county had no authority to issue bonds for such a purpose. The invalidation of the bonds led to the end of Moore's involvement with the canal. The supreme court decision confirmed the county commissioners' concerns and fears regarding the bond issue at the time they were being pressured by Moore, the Seattle Chamber of Commerce, and the opinion of Prosecuting Attorney Mackintosh to move forward with the special election in September 1906.

In February 1907, even before the court ruled, the Lake Shore Owners Club began taking the necessary steps to take over the canal project. On March 22, 1907, the Lake Shore Owners Club became the Lake Washington Canal Association (LWCA). Members included John McGraw, Thomas Burke, George Alexander Virtue (1862-1935), C. E. Remsberg, and Roger Sherman Greene (1840-1930), with John Stuart Brace (1861-1918) as president. The LWCA was formed specifically to obtain the rights to the canal from Moore in order to negotiate new terms for funding canal construction and to protect the interests of property owners on Lake Union and Lake Washington. On June 10, 1907, one day short of a year after receiving federal authorization for his project, Moore assigned the canal right-of-way to the LWCA. The association in turn transferred the right-of-way to King County and the county reassumed direct responsibility for building the canal.

In the End

In the end, the Army Corps of Engineers took on the task of building the canal, following plans devised by Chittenden to eliminate the deficiencies he had identified in Moore's plan. Chittenden called for two locks -- built of concrete, not timber, and larger than those Moore proposed -- at the mouth of Salmon Bay, raising the level of the bay to that of Lake Union. As in Moore's plan, Lake Washington was lowered to the level of Lake Union. Chittenden retired due to ill health in 1910, and construction of the locks and canal he designed was supervised by his successor as Seattle District Engineer, James Bates Cavanaugh (1869-1927). The Lake Washington Ship Canal opened to boat traffic in the fall of 1916. Its grand opening was celebrated on July 4, 1917, exactly 63 years after Thomas Mercer had suggested the canal connection.

James Moore's beloved wife of 23 years died on September 5, 1908. He moved in 1914 to California, settling in San Francisco. Moore continued to invest in other projects. James A. Moore died at the age of 67 on May 21, 1929, at the Palace Hotel in San Francisco, with his second wife, Elsie Clark Moore, at his side. The cause of death was given as a strained heart, and it was said Moore died of overworking himself. Funeral services were held at the Chapel of Cypress Lawn Memorial Park in San Francisco.