During the summer of 1906, Laurence J. Colman -- member of a prominent pioneer family and a longtime supporter of the Young Men's Christian Association in Seattle -- invites the YMCA to camp on the family's waterfront property on Orcas Island. This is the beginning of Camp Orkila, one of the oldest organized boys' camps in the Pacific Northwest.

The Seattle YMCA had been associated with camping since 1891, when Thomas S. Lippy, then the organization's physical education director, set up a three-month summer camp at Green Lake. The facilities were rustic, consisting of a cluster of tents on the lakeshore, semicircled around a campfire, with a latrine out back. The camp was open to all members of the Y, for a fee of $5 a week. The boys (most were actually young men, over age 14) went boating, swimming, and fishing. They also spent one or two hours a day in Bible study.

The predecessor to Camp Orkila was a series of boys' camps held on Hood Canal between 1899 and 1905. These camps included a strong emphasis on nature study. In the last of these camps, 30 boys spent six weeks at Hoodsport, supervised by H.A. Woodcock, educational director of the YMCA. They built a sloop and sailed it back to Seattle, bringing with them 93 stuffed animals and birds.

The Colman family apparently stopped using the Orcas Island property after 1906, and the YMCA campers kept coming back on a guest basis year after year. Ruth Norman, the camp's resident nurse and wife of Charles G. Norman (camp director from 1923 to 1946) is credited with coming up with the name "Orcila" in 1924, an abbreviation for Orcas Island. Because so many people who saw the name in print insisted on pronouncing it "or-sill-a," the spelling was officially changed to Orkila in 1938. That year, Kenneth Colman, son of Laurence, deeded the property to the YMCA.

Like other camps of the era, Orkila in the early days was characterized by tight schedules, planned by the adult leaders. Timed hikes were common and organized sports were emphasized. As one former camper recalled, "A boy just had to learn to play baseball and run in a track meet if he was to have a good time" (Craven). Campers were expected to spend two hours each morning working on camp improvement projects. The brochures warned that the camp was "no place for 'loafers'" ("What's Doing This Summer?").

Frank Pritchard, a longtime volunteer for the YMCA, remembers Orkila in the early 1930s as having a quasi-military atmosphere. "Every day after breakfast we had to rush back to our cabins and clean them and sweep them out and clean ourselves up -- making sure our nails were clean and so on -- and line up for inspection," he says. "The director would come along and inspect the cabin and look at our necks and check our fingernails. It was like being in the army" (Pritchard interview).

There was also a strong religious component. Along with their own bedding, towels, and eating utensils, campers were required to bring a New Testament to camp. Smoking, card playing, and the use of profane or obscene language was "positively prohibited" ("Camp Orcila: Paradise for Boys"). The camp's focus was on the development of Christian character and leadership in a marine-oriented environment. As late as 1963, boys applying for camp at Orkila were asked what church they attended.

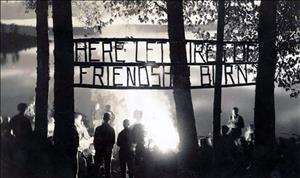

Girls were invited to camp at Orkila on a gradual basis beginning in 1967; since 1971, the camp has been entirely co-ed. The privies are long gone, along with the canvas tents and the rudimentary sanitary facilities, consisting of a cold water faucet, a comb tied to a tree with a string, and a cracked mirror tacked to the trunk of the tree. What remains is the magnificent physical setting, as unspoiled today as it was when the Colman family first offered to share it with the YMCA.