On November 25, 1892, Hans J. Claussen (1861-1937), Charles E. Crane (ca. 1853-1918), and George E. Sackett (ca. 1843-1921), owners of the Seattle Automatic Refrigeration Company, incorporate the Diamond Ice & Storage Company. Diamond Ice later takes over Seattle Automatic Refrigeration's manufacturing facility, housed in several wooden buildings at Western Avenue and Union Street. The company delivers the ice it makes to businesses and homes around the city, where it is used in ice boxes to chill perishable foods. The arrival of electric refrigerators in the early 1920s will greatly lessen demand for ice, and the company will permanently cease production of ice for sale in May 1949, while still offering cold storage.

Natural Ice vs. Artificial Ice

Diamond Ice sold so-called artificial ice, rather than natural ice. Natural ice (ice formed when water solidifies due to external temperatures falling below freezing) was harvested from ice caves, lakes, and rivers in Washington Territory beginning in the 1860s, but the quality and available quantity varied widely, and melt was a constant threat. An 1869 article in The Commercial Age, an Olympia publication, quoted in Jacqueline B. Williams's 1996 book The Way We Ate, explained the difficulty of transporting natural ice harvested from ice caves near The Dalles, Oregon: "The ice is quarried in slabs at 200 lbs; and two of these wrapped in gunny bags are loaded upon each animal [mules and horses]. The distance to the steamboat landing on the Columbia is about 35 miles, and the loss in transportation is nearly 50 percent" (Williams, 31).

In colder winters, the thin sheets of ice that formed on Seattle's Lake Union were harvested and stacked so that they would freeze together, forming more substantial and longer-lasting chunks. Seattle's maritime climate made such lake-ice harvests hit or miss, in contrast to natural ice harvested in Eastern Washington, where consistent cold weather made ice formation more dependable.

Prototypes for equipment to manufacture artificial ice were patented in the early 1850s and refined in the following decades. Artificial ice became more important commercially during the late 1880s. The New York Times took up the odd "artificial" nomenclature in an 1890 article:

"The Boston Purists have broken loose again and are protesting vigorously against the term 'artificial ice.' They assert that the product of the ice-making machines is 'ice' -- neither 'artificial' nor 'imitation' ice. Guess they are about right: yet how is the stuff to be distinguished by name from 'natural ice'?" ("Little Efforts to Amuse").

Puget Sound Ice Company

From 1872 to 1874, Seattleites in need of ice could order delivery from the Puget Sound Ice Company. The company originally planned to ship ice down from Sitka, Alaska, but ultimately took it from the Sierra Nevada Mountains in Nevada, from where it went by rail to San Francisco and was transported by bark to Seattle. The ice was stored in an insulated ice house at the foot of Mill Street (later renamed Yesler Way).

Some sources state that when the first shipment of ice was used up, which took two years, Puget Sound Ice went out of business, but this appears to be incorrect. Seattle city directories of the 1880s carried listings for Puget Sound Ice. A 1958 Seattle Times article states that in 1882 Arthur Denny (1822-1899), Dexter Horton (1825-1904), and other Seattle financiers put up $10,000 to build an artificial-ice plant, but it is unclear if this was a separate operation. Puget Sound Ice Company's advertisement in the 1887 Polk's Directory states that its plant produced 20 tons per day, a clear indication that the firm by then sold artificial ice, rather than natural ice. The company provided Seattle with ice until the plant, located at Western Avenue and Seneca Street, burned in the 1889 Seattle fire.

The Iceman Cometh

On November 25, 1892, Hans Claussen, Charles Crane, and George E. Sackett, who owned the Seattle Automatic Refrigeration Company, incorporated a new firm, the Diamond Ice & Storage Company. Somewhat later, Diamond Ice moved into several wooden buildings at Western Avenue and Union Street that had been Seattle Automatic Refrigeration's manufacturing facility.

Diamond initially contracted with the Renton Co-operative Coal Company for use of its horse-drawn vehicles for deliveries. A 1957 Seattle Times article recalled, "The ... company delivered to hotels, restaurants, saloons, ice-cream companies, and homes. It handled the icing of railroad cars and shipped ice, packed in burlap sacks, to nearby points" ("What Happened to the Ice Man?").

Icemen had delivery routes and customers indicated how much ice they required, using a card printed with a different weight (25, 50, 75, 100) on each side or corner. Households posted this card in their front windows. Ice-box size, and the weather, determined ice requirements. Icemen weighed or estimated weight for each order and carried the ice onto the back porch or into the kitchen and placed it in the icebox. A block of ice lasted about a day.

Ice boxes were usually wooden (often oak, pine, or ash) and lined with zinc, galvanized metal, wood, slate, or porcelain. Insulation material such as straw, charcoal, cork, or mineral wool (artificial felt made by spinning molten glass or mineral materials), and layers of airspace slowed melting. Melted water drained into a pan on the bottom of the box or sitting on the floor under it. Before the invention of gas and electric refrigerators, ice boxes were often advertised as refrigerators.

Hard Sell

Diamond's early advertisements set out to convince Seattleites that purchasing ice to chill their perishables was a prudent choice: "It is poor economy to allow milk, butter, and meats to spoil for want of a little ice, which costs less per day than the loss would be. Diamond Ice -- Telephone Pike 159 -- is what you want" (The Seattle Times, May 29, 1897).

One week later, Diamond made the case for its product based on quality. Under the heading "Ice vs. Snow," Diamond's ad stated:

"Don't buy snow from our competitors when you can get Crystal Diamond Ice. Made by the new process (no core in it) which will last twice as long, because it is FROZEN HARD. Some people buy the cheapest, regardless of quality or durability. Others use their brains and compare the goods. To such we recommend Diamond Ice. Buy a coupon book (25-pound size is the best and cheapest), and save 25 per cent on your ice bill" ("Ice vs. Snow").

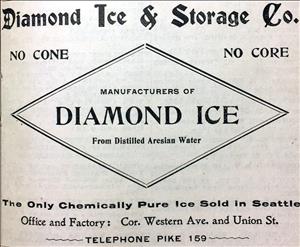

By the next year, Diamond's advertisements had been distilled to a calm single line: "Diamond Ice is pure" (The Seattle Times, June 11, 1898). And in the 1899 Polk's City of Seattle Directory, it promised customers "No cone. No core. Distilled from Ar[t]esian water. The only chemically pure ice sold in Seattle" (1899 Polk's, 1096). Using distilled water helped produce clear, rather than opaque, ice.

Cold on Call

Crystal Diamond Ice was harder, more attractive, and slower to melt than natural ice. An 1897 Seattle Times article announcing that Diamond would be offering direct delivery rather than contracting out that service dismissed ice made by its competitors as "soft snow ice that will not only have a core in it, but will melt if you look at it" ("A Card to the Public").

The company leaned heavily on Seattle residents to buy their ice from Diamond, even implying that doing so satisfied a civic duty:

"Our ice is made in Seattle, and the stockholders of the company are Seattle men, who work for its interests. By giving us your trade we feel you help yourselves as well as the Diamond Ice & Storage Company" ("A Card to the Public").

Hot and Cold

Seattle's icemen unionized in April 1900. In 1902, Diamond's owners organized and began operating the Mutual Light & Heat Company. The plant supplied steam heat and electricity to part of downtown Seattle. The Seattle-Tacoma Power & Light Company purchased Diamond Ice & Storage and Mutual Light & Heat in 1905. Diamond Ice eventually became a subsidiary of the Puget Sound Power & Light Company, part of the Stone and Webster conglomerate.

In 1911, Diamond Ice razed its original wooden buildings and erected a four-story concrete structure with twice the capacity. This building, which opened in 1912, was in 2018 a Public Storage facility, using the address 1334 Alaskan Way.

A 1957 Seattle Times article identifies Diamond Ice as Seattle's "first mechanically refrigerated ice plant and warehouse" ("What Happened ..."). Dating at least from the time the 1912 facility opened, and possibly before, Diamond Ice used the so-called shell-cooler method, utilizing liquid ammonia and pipes filled with calcium chloride to freeze water into ice. A minute air tube blew air through the water as it froze in order to keep it circulating. This process made the finished product transparent, rather than cloudy. It took 36 to 48 hours for the 9000-pound plates of ice to form. The ice was lifted to a horizontal position using an electric crane and cut to smaller size using a circular saw. The Diamond Ice plant turned out 60 tons a day.

Diamond Ice persevered even as smaller companies failed. In 1906 the Seattle Mail and Herald decried the question of whether Diamond held Seattle in the grip of an "Ice Trust." "People here get ice cheaper than they do in Portland, Los Angeles and other cities of the grade, and have done so for years. It costs more to deliver ice in this city than in most cities because of the hills" ("The Ice Trust Bugaboo").

Enter the Refrigerator

The earliest household refrigerators cooled with electric motors appeared in 1887. They were not widely available, and their technology had not yet been perfected. During the late 1910s, several companies manufactured equipment that could be used to retrofit iceboxes for electricity, but they were expensive and difficult to service.

Electric refrigerators were first mentioned in The Seattle Times in 1905: "Heretofore the difficulty has been to make a practical apparatus small enough to use for the average household ... Now, it is claimed, a smaller electric refrigerator is about ready for general introduction, which will take the place of ice boxes which now use 100 pounds daily" ("Electric Refrigerator"). This announcement was premature -- the newspaper's first advertisement for an electric refrigerator (a Frigidaire) ran on September 24, 1922.

Frozen Out

As mechanical refrigerators eclipsed ice boxes in Seattle households, demand for ice delivery dissolved. In 1938, Diamond converted half of its ice-making space into cold storage and freezer space. Cold storage and freezers could preserve perishable foods over time, making these facilities an important part of the commercial food chain. Diamond ceased ice production and delivery service in 1941, although it still offered cold storage. Diamond's ice production resumed during World War II, but ceased for good in May 1949. A 1969 Seattle Times article called Rainier Ice & Cold Storage -- formerly one of Diamond Ice's competitors -- "the only ice works in the city" ("Ice-Making -- It's Big Business").

In 1966 Diamond Cold Storage's Seattle facility and the Seattle portion of the business were sold to the Olympic Cold Storage Company, a former competitor. Diamond's building at 1331 Western Avenue became Olympic's Cold Storage Warehouse No. 2. At the time of the sale, Diamond had a second plant in Auburn. In 1977, the West Coast Grocery Company, a Tacoma firm, purchased the Auburn operation.

By 2018, only five cold-storage companies held Seattle business licenses, and none offered ice delivery. Most businesses requiring ice for beverages or, for example, crushed ice on which to display fresh fish, used their own relatively inexpensive commercial ice machines.

However, ice delivery remained available to both wholesale and retail customers throughout the Puget Sound region via a Tacoma firm, Star Ice and Fuel. One hundred thirty years after its founding in 1888, Star was delivering party ice, shaved ice, block ice, and dry ice, and offering a 24-hour emergency service in case of power outage or equipment failure. The company's website stated "Each piece of ice is blast-frozen, sized and touched only by stainless steel surfaces from freezing to packaging" ("About Star Ice and Fuel").