On December 31, 1918, the Seattle City Council approves purchasing the city's privately owned streetcar system for $15 million in utility bonds. The purchase gives the city full control of its streetcar system. But not known at the time is that issuing the 20-year utility bonds to pay for the purchase saddles the city with onerous debt that will result in financial calamity. The council's decision to authorize the bonds comes after Seattle voters in November 1918 overwhelmingly approved buying the Puget Sound Traction, Light & Power streetcar system. City residents have been frustrated by the privately run system's plethora of problems -- including pressure from city officials, mounting tax obligations, and dilapidated tracks and equipment -- and inability to handle the overwhelming increase in riders due to industrial buildup during World War I. After months of haggling, the city and the company agreed on the $15 million price tag. Voters apparently cared less about the cost and more about getting rid of the private transit monopoly.

Increasingly Frustrated

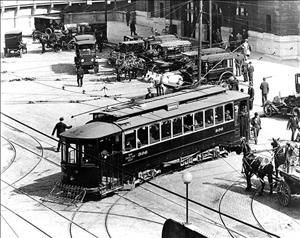

In the second half of the 1910s, a burst of World War I wartime production in Puget Sound created an influx of new workers, all of whom needed to get to and from their shipyards and airplane factories. Yet the Puget Sound Traction, Light & Power streetcar system was already dilapidated and overcrowded and couldn't handle the increase in riders or the continual scrutiny by the Seattle city officials.

Residents viewed the Puget Sound Traction, Light & Power system, owned by national utility giant Stone & Webster, as a monopoly and wanted change. City officials had also been increasingly frustrated and impatient with the Stone & Webster ownership -- especially since they saw the company as a competitor to the city's own fledgling streetcar system. The old private streetcar system was not up to the challenge and was handling "twice the traffic it was built for" (Kershner).

In May 1918, the company met with the city and attempted to get relief from two of its biggest problems. First, it wanted to raise the five-cent fare that had been imposed under its original franchise agreement with the city. Second, it wanted to be freed from the tax obligations it owed to the city. In response, Mayor Ole Hanson (1874-1940) wrote an "outraged scream" of a letter (Kershner) to the Seattle City Council in which he accused the company of packing the public "into suffocating, dirty, unsanitary cars like bananas in a bunch. ... Conditions are all but unbearable, and the service unspeakable" ("Mayor Ole Hanson's denunciation ...").

As for the nickel fare, city officials believed -- with plenty of evidence -- that the public would be appalled by any fare increase. Instead, the city demanded the company pay for paving between its tracks, essentially paving many of Seattle's streets. This was an increasingly important issue, since more autos were sharing the roads. At the same time, the federal government implied that if Seattle's transit mess wasn't cleared up, it would yank its Seattle shipbuilding contracts.

Offer and Acceptance

Faced with all this pressure, Puget Sound Traction, Light & Power offered to sell its entire transit system to the city for $18 million. The company claimed that this price was a bargain, because it had spent $19 million fixing up the system. Hanson countered with $15 million, extrapolated roughly from how much the city had just spent, per mile, to build its own municipal lines.

The company accepted the $15 million offer with startling alacrity, which only increased public suspicion that this was no bargain. These suspicions were correct. Hanson's estimate was based on the faulty assumption that the old system's dilapidated tracks and equipment were worth what the city had just paid for its own brand-new tracks and equipment. One city council member estimated that the true value of the system was "only about $5.5 million" (Kershner).

Voters apparently cared less about the price tag and more about the opportunity to rid the city of the private monopoly. In the November 1918 general election they approved, by a three-to-one margin, buying the streetcar system for $15 million. The vote was only advisory. That's why the Seattle City Council had to issue the 20-year utility bonds to pay for the system.

Bonds Approved

On December 31, 1918, in a 5-to-2 vote, the council approved the issuance 20-year utility bonds for that purpose, which meant Seattle's new possession was saddled with debt from day one. At the time, however, city officials celebrated the decision. Mayor Hanson told The Seattle Times after the council vote:

"Seattle has blazed the way for municipal ownership of public utilities for the whole nation ... It will be our duty, upon the property being delivered to the city, to conduct our transportation system in such a manner that it will reflect lasting credit on the city and give the people the service that has been denied them" ("Car Lines ...").

The paper also reported that the purchase "is said to be the largest municipal ownership transaction ever undertaken by any city in the world and will make Seattle the only city of its size in the United States owning and operating a complete street railway system" ("Car Lines ...").

"A Bully Good Trade"

On March 31, 1919, Puget Sound Traction, Light & Power officially turned over the deeds and contracts for streetcar system to the city in return for the $15 million in bonds, and the city of Seattle became the sole owner of the entire streetcar system.

History has been unkind to this transaction. It inaugurated 20 years of fiscal chaos. Seattle street railway historian Leslie Blanchard believed that it would have been better if the city had simply let the franchise expire in 1935 and send Stone & Webster packing then. At that point the city could have spent far less than $15 million to upgrade the system to modern standards.

Historian Walt Crowley concluded that the city's system was "crippled from the beginning by the debt of the system's purchase, which cost $833,000 a year in interest alone" (Crowley, 14). In 1991 Seattle civic historian Richard C. Berner concluded that the sale was "an almost satanic calamity for the city" with repercussions far into the future (Berner, 268). Two decades of system decline and brutal political warfare would ensue. Nobody benefited except one particular entity. Berner uncovered an internal letter from a top Stone & Webster executive, who called it "a bully good trade for the company" (Berner, 268).