On December 23, 1918, heavy rain causes a blowout in the glacial moraine along the Cedar River Watershed, sending hundreds of thousands of gallons of water, mixed with gravel and detritus, down small Boxley Creek. Later known by some as the “Boxley Burst,” the disaster destroys the logging community of Edgewick, but spares the lives of every resident therein.

A River Ran Through It

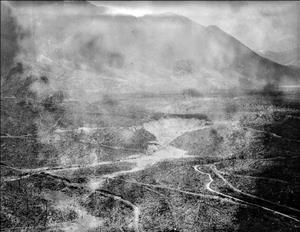

Cedar Lake (now Chester Morse Lake), three miles east of Rattlesnake Lake and several hundred feet higher, feeds Rattlesnake Lake, which in turn feeds Boxley Creek. The Cedar River watershed feeds Rattlesnake Lake specifically from seepage through the glacial moraine beneath Cedar Lake.

In 1914, the City of Seattle began building a masonry dam on the Cedar River between Cedar Lake and Rattlesnake Lake. The dam was needed to impound water to generate electric power for City Light. During the four-year construction, a 12-foot diameter opening was left in the foot of the dam to allow the river to flow freely during construction. In October 1918, the project was completed and the hole was plugged.

For the next two months, water gradually rose behind the dam. As a small lake filled the valley between the dam and Cedar Lake, more water seeped into the ground and through the moraine. Below the dam, Rattlesnake Lake swelled, causing more runoff into Boxley Creek. In December, the rains came, and with them, disaster.

Down in the Valley

By the morning of December 23, 1918, there was too much rain. Before sunrise, a landslide and washout occurred near the masonry dam. A surge of water sluiced half a million cubic yards of earth and gravel away from the hillside. The churning mass roared down the small valley leading to Boxley Creek. Within minutes the little stream turned into a 150-foot wide river. Directly in its path was the little community of Edgewick.

Edgewick was a company town built for the North Bend Lumber Company (NBLC) by owners Robert Vinnedge and William C. Weeks. The name of the town came from combining their names -- the last syllable of Vinnedge followed by “Wick,” a popular pronunciation of Weeks. The first sawmill at Edgewick was built in 1906, and by 1918, the little community consisted of 18 identical row houses for families, a bunkhouse for single workers, a kitchen, a dining room, and a company store. The mill and the town were located at the foot of Boxley Creek as it drained into the South Fork of the Snoqualmie River.

Run for the Hills

Standing in torrential rain, NBLC night watchman Charles Moore had been keeping a close eye on the creek as it pushed up against a dam built for the millpond. Throughout the night, the water had been slowly rising, but then the creek began swelling by a foot or more every two minutes.

Moore realized that a break had occurred upstream, and that he had to immediately warn the townspeople sleeping in their homes below. Acting quickly, he tied down the whistle with a length of cord. As the whistle shrieked out over the falling rain, he ran through the town, battering on every door. “Out of your beds!” he screamed. “The dam is going to go!”

There was no time to waste. Some folks dressed quickly, but many ran from their homes in nightclothes, clutching a hastily grabbed shirt, blouse, or pair of pants. As the community gathered outside in the downpour, they heard a sickening crunch upstream, followed by a deafening roar. Their dam had just given way, and they were right in the floodpath.

Men, women, and children frantically rushed for high ground, fearing the worst. Fortunately, circumstances gave them a few extra seconds that probably saved their lives. Before the swell could reach them, it crashed into the main mill, which acted as a barrier, if only temporarily. Ankle-deep water quickly rose to waist-deep. As the last folks climbed out of the way, the water was almost up to their necks. The mill buckled and collapsed. Everyone on the dark hillside caught their breath, as they heard the remains of their town carom through the raging current below.

Swept Away

As quickly as the flood had begun, it ended. Once the surge of water joined with the Snoqualmie River, the levels at Boxley Creek began to drop. The 60 or so ex-residents of Edgewick built a small fire on the hillside and huddled around it in shock. Tomorrow would be a cheerless Christmas Eve, but at least they were alive.

As morning broke, they peered into the valley at what had once been their home. Almost every building was destroyed, some completely obliterated. The company owned the houses, but everyone’s personal belongings were now strewn amidst mud, rock, and timber. Some families lost all that they owned.

Downstream, North Bend officials saw the mill debris in the Snoqualmie River and sent a train to Edgewick to help with the recovery. Four families rode the train back to North Bend, but everyone else stayed, hoping to find things that were once theirs. For now, all they had were the clothes on their backs.

Picking up the Pieces

The disaster was devastating for Vinnedge and Weeks, beyond their business concerns. Vinnedge and his wife had just lost a daughter to a spinal disorder, and were recovering in California at their doctor’s behest. They returned after receiving word that their home in Edgewick had been destroyed. Weeks was dealing with his own personal tragedy: His wife had died days before in the worldwide flu epidemic, leaving him to raise their three small children on his own.

The NBLC began salvaging in the spring, but there was no hope of rebuilding and resuming operations. They sold what little equipment was still usable, trying to cover their losses. They also fought with the City of Seattle for damage compensation, but litigation dragged on for almost 10 years. After seemingly endless lawsuits and appeals, in April 1928, the courts awarded NBLC $361,867.81.

By this time, the town of Edgewick was mostly a memory, and although it was never formally renamed, many locals now referred to the stream as Christmas Creek.