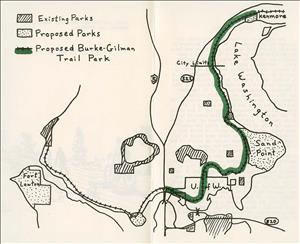

On August 19, 1978, Seattle and King County officials gather to inaugurate 12.1 miles of the Burke-Gilman Trail, built along a former rail corridor previously owned by Burlington Northern Railroad. The dedication is the culmination of seven years of negotiations, community meetings, civic advocacy, and support from environmental and recreation organizations. A citizen group from the Matthews Beach neighborhood helps raise support for the recreational corridor when it organizes a hike-in and rally in 1971 that draws more than 2,000 residents. Following months of negotiations, Burlington Northern agrees to exchange the abandoned rail bed for other Seattle and King County property. At the time of its dedication, the trail runs from Seattle's Gas Works Park to King County's Tracy Owen Station in Kenmore. Eventually, the Burke-Gilman Trail expanded to cover 18.8 miles, connecting Golden Gardens Park in Ballard to Blyth Park in Bothell, where it joins the Sammamish River Trail.

Dedication Ceremony

The dedication of the Burke-Gilman Trail was held at noon on Saturday, August 19, 1978, at Matthews Beach Park, just off of Sand Point Way NE at NE 93rd Street. Participants included Seattle Mayor Charles Royer (b. 1939), King County Executive (and later governor) John Spellman (1926-2018), and members of both the city and county councils.

To promote the trail's two primary uses, groups of runners and cyclists were engaged. A group of cyclists rode from the new Logboom Park at Kenmore (also dedicated that day) to Matthews Beach Park, transporting a pennant with the King County logo. From the opposite end, runners and joggers left Gas Works Park in Seattle. Both groups met up at Matthews Beach Park, kicking off the dedication ceremony and speech-making.

The Original Railroad Corridor

The Burke-Gilman Trail follows a former right-of-way of one of Seattle’s first railroads -- the Seattle, Lake Shore & Eastern Railway. The SLS&E was established by a group of 12 investors that included Judge Thomas Burke (1849-1925) and businessman Daniel Gilman (1845-1913), whose names were linked a century later to the mixed-use public trail.

Burke, Gilman, and their fellow businessmen were frustrated by promises made and broken over the years to connect the Pacific Northwest by rail with the rest of the country. In 1885, they raised funds to build their own rail line. The first segment of the SLS&E, which opened in 1887, ran from downtown Seattle to Woodinville. The businessmen continued to push the line northward, hoping to connect with the Canadian Transcontinental. More track was laid to the east with Spokane as the terminus, but the SLS&E never made it over the Cascade Mountains or to the Canadian border. In 1892, the SLS&E was absorbed by Northern Pacific Railroad.

"As part of the NP system, the former SLS&E lines mostly contributed timber and coal traffic, provided car-ferry service along Puget Sound, moved other general merchandise freight, and operated local passenger service. As early as the 1920s, passenger train schedules were reduced and ended entirely between Seattle and Woodinville by 1938. The railroad did, however, continue to offer excursions and fan trips along the route through the 1960s" ("Burke Gilman Trail History"). In 1970, Burlington Northern Railroad was formed from a merger and a year later, the company applied to abandon the rail line and sell the property.

Hike-in and Rally Capture Public Attention

Conversations arose between the League of American Wheelmen, Seattle Parks and Recreation, and city engineers about creating a pathway that would take cyclists from the University of Washington campus to the city limits. In 1968, a group of neighbors living in Matthews Beach, about two miles northeast of the University of Washington, formed the Burke-Gilman Trail Park Committee.

Matthews Beach resident Merrill Hille (b. 1939), a trail park committee member, often used the railroad overpass to cross Sand Point Way when out on walks with her family. Hille later remembered, "There was no railing, so we made the kids walk between the rails to get there so they wouldn't fall over the edge" (Banel).

Representing the neighborhood group, Hille met with Seattle Mayor Wes Uhlman (b. 1935), who encouraged her to get creative about drumming up public support. On September 12, 1971, the committee organized a hike-in, attracting hundreds of people who marched along the shores of Lake Washington. They came from both the north and the south end to converge at Matthews Beach Park, where signatures were collected. "Jim Todd, chairman of the Burke-Gilman Trail Park Committee, said his group is mailing a petition with 1,600 signatures asking that the property be donated to the public by Louis W. Menk, B.N. [Burlington Northern] president" (Parks).

Mayor Uhlman endorsed the project wholeheartedly and spent significant time and political capital pushing for its support, but not everyone was as enthusiastic. "Some homeowners feared the proposed trail would become a vector for crime, and that their property values would drop ... This was also the time of the 'Boeing Bust,' when massive layoffs had put the local economy into a tailspin" (Banel).

Uhlman persevered. "I felt very strongly that this was almost kind of a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity, to have a trail go through the middle of Seattle ... And so I held my guns" (Banel). Other conservation groups joined the cause, including the Sierra Club and the Izaak Walton League.

A Trail is Born and Named

When the neighborhood committee began researching the property's provenance, the names Burke and Gilman appeared frequently in old property records and regional histories. Inspired by the activities of these businessmen a century earlier, the group named their working committee the Burke-Gilman Trail Park Committee. The name stuck.

In February 1973, Burlington Northern ceded the railroad line in exchange for industrial property north of downtown Seattle. King County worked out a separate arrangement to secure the rail corridor north of Seattle to Kenmore.

According to Hille, Seattle Parks Department spent $10,000 on signage featuring the Burke-Gilman name before the city council met in 1974 to officially approve the designation. Luckily there were no objections.

Since its opening, there have been extensions to the original trail and the 18.8-mile Burke-Gilman connects with other trails on the Eastside, north to Snohomish County, and across the Cascades. "The feared trail-based crime wave never materialized, and proximity to the Burke-Gilman soon became a selling point for homes and apartments along the route" (Banel). The route is used by thousands each day, connecting business centers, cultural and recreational destinations, hospitals, neighborhoods, and the University of Washington campus.