On September 29, 1978, the Seattle School District begins mandatory, district-wide busing of students to achieve racial balance. Limited mandatory busing (involving four middle schools) had been in effect since 1972.

Seattle's schools had become increasingly segregated as a result of decades of housing discrimination, with students of color concentrated in schools south of the Lake Washington Ship Canal. At Garfield High School, for example, more than half the students were African Americans, compared to only about 5 percent of the students in the district as a whole. Predominantly nonwhite schools generally got fewer resources from the district than predominantly white schools.

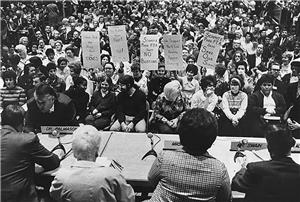

Responding to the threat of legal action by civil rights groups, the Seattle School Board adopted a limited busing plan to desegregate the district’s middle schools in 1970. Implementation of that plan, involving about 2,000 students, was delayed for two years by a lawsuit filed by an anti-busing group. In 1977, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), and the Church Council of Greater Seattle threatened to seek federal intervention unless the district took more aggressive action.

Convinced that a homegrown plan would be better than a court-ordered one, Seattle became the first big city in the United States to voluntarily undertake district-wide desegregation through massive, cross-town busing. In the first year of what became known as the Seattle Plan, about 12,500 of the district’s 54,000 students were bused to schools outside their neighborhoods.

The plan was implemented without incident, although the opening of school was delayed for three weeks because of a teachers' strike, which was ended by a court order. "We find it paradoxical that school will be opened Friday with court-ordered teachers and voluntary desegregation," commented Richard L. Andrews, chairman of the Seattle Public Schools District-Wide Advisory Committee for Desegregation (The Seattle Times, 1978).

The Seattle Plan was endorsed by a broad coalition of city officials and community groups, including African American and Asian community leaders, both the outgoing and the newly elected mayors, the Chamber of Commerce, religious leaders, the League of Women Voters, the Municipal League, and the teachers' association. However, two months after it went into effect, 61 percent of Seattle’s voters (and 66 percent statewide) approved an anti-busing initiative sponsored by the Citizens for Voluntary Integration Committee, headed by Seattle businessman Robert O. Dorse. The initiative was declared unconstitutional, in a case that reached the U.S. Supreme Court in 1982, but the vote was a reminder of grassroots resistance to busing.

The School Board began to phase out mandatory busing in 1988, introducing a "controlled choice" plan that let parents select a school for their child from within a cluster of schools. The following year, Seattle voters approved a local anti-busing initiative that promised to give the school district 6 percent of all city revenue in return for an end to mandatory busing, with the money to be used to improve neighborhood schools. The School Board turned down the extra money, meaning the initiative had no effect, but it was clear that political support for busing was collapsing.

Busing for the sake of desegregation ended in Seattle’s elementary schools in 1997 and in middle and high schools two years later.

"My job was to avert a federal lawsuit by coming up with a plan of our own, and we were successful in that," said David Moberly, superintendent of the district from 1976 to 1981, looking back on the busing experiment. "Was the plan successful educationally? No. I don't think it did anything to enhance the academic achievement of minority students" (The Seattle Times, 2001).