On April 25, 1895, an article appears in the Everett Herald featuring rare details about one of the Pacific Northwest’s first guitar-makers, Mr. W. O. Welch. The story apparently was originally published in Monte Cristo’s Mountaineer newspaper before being picked up in Everett. The occasion for this news coverage was that a local businessman, John Ross, had recently made a visit to the Snohomish County mining town of Monte Cristo, where he crossed paths, and conducted a transaction, with Welch.

The Rise of Monte Cristo

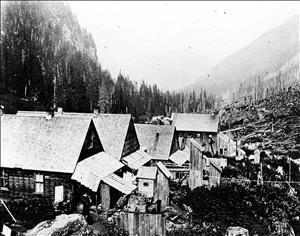

Monte Cristo, Washington, was a rip-roaring boomtown carved out of the Cascade Mountains about 37.5 miles east of Everett. Glittering gold and/or lead-silver deposits had first been spotted nearby by Joseph Pearsall in the summer of 1889. Other miners hiked in and began staking claims by 1890, and a ramshackle village took form along the South Fork of the Sauk River. Named Monte Cristo as a nod to the hugely popular romantic adventure serial, The Count of Monte Cristo (first published between 1844 and 1846) by Alexandre Dumas (1802-1870), the town's core residential strip was cleverly named Dumas Street.

In 1891 New York financier John D. Rockefeller (1839-1937) took an interest in the area's mineral exploration, and his investment syndicate -- which included two members of the Northern Pacific Railroad’s executive committee, Charles L. Colby (1839-1896) and Colgate Hoyt (1849-1922) -- soon bought out numerous other interests and eventually controlled two-thirds of the area’s most promising mines and claims. The Everett and Monte Cristo Railroad was built along the Sauk River in 1892 to haul ore from the mines down to a smelter in Everett, a town that would soon have major avenues with names like Rockefeller, Colby, and Hoyt.

By 1893 -- when Colby and others formed the Monte Cristo Mining Co. -- there were 211 claims in the area and approximately 200 men employed as miners as well as engineers, mechanics, and other mining-industry support crews. A town began taking shape, with the residential cabins clustered up along Dumas Street toward the northeastern end of town, located opposite the rowdy miners’ cabins, heavy industry, and godless saloons a few hundred feet west at the other end of town, just below the railroad turntable/roundhouse.

At that time Monte Cristo could boast a "post office, 7 saloons, 2 dance halls, 1 tailor shop, 1 newspaper -- the Monte Cristo Mountaineer, 1 meat market, hotels, rooming houses, boarding houses, stores, [h]orse barns, bachelor quarters, maid quarters, girl quarters, family residences, blacksmith shop, machine shop, cobbler, 1 church little used," and one small "jail not used at all" (Strom). Among the five hotels was one operated, legend holds, as a brothel by Frederick Trump (1869-1918), German immigrant and grandfather of the future U.S. president.

W. O. Welch

Where exactly W. O. Welch's cabin was located in Monte Cristo remains unknown. Indeed, little about Welch is certain other than that he was a mechanic who had woodworking skills and -- as area resident, Monte Cristo Preservation Association board member, and HistoryLink contributor David Cameron has written -- may possibly be the same William Welch who was born in Missouri in 1851 and then lived for a spell in White Horse, Washington, a tiny settlement between Oso and Darrington (on today’s Highway 530).

What is known is that in the mid-1890s it was not uncommon for mining company executives (and other curious investor types) to take trips from Everett to Monte Cristo to inspect the mining operations. And, it seems that some of them liked to bring back souvenirs. John Ross -- who may have been the same fellow as a co-founder of Seattle’s Lake Washington Coal Company -- commissioned from Welch an "elegant cane made of Alaska and dark red cedar in four alternate parts" and he was said to treasure it and "will have it properly mounted ... a memento of his sojourn in Monte Cristo" (Everett Herald).

In his definitive book, Monte Cristo, historian/author Phillip R. Woodhouse noted that Welch was a fellow "who fashioned objects from local woods with the skill of an accomplished craftsman. Welch specialized in musical instruments: he built violins, guitars, and viols from spruce and yellow cedar. He also manufactured inlaid canes and other wooden objects. His work was in much demand, and many company officials returned home from Monte Cristo with one of his instruments" (Woodhouse).

Indeed, Welch seems to have had his hands full in 1895: "Mr. Welch is now manufacturing an inlaid guitar of grand concert size, also a violin both of Alaska and mountain cedar. He is doing quite a stroke of business in the native woods and will probably make a large sized bass viol next" (Everett Herald).

The Fall of Monte Cristo

Monte Cristo's promise of providing riches never panned out. Not only had geologists overestimated the potential ore to be found, but the town's location on steep hillsides next to an unruly river also helped seal its fate. Major fall flooding in 1896 washed out railroad track and damaged tunnels, a scenario repeated in 1897. The expense of repairs, and the sheer hardship of life in the Cascades, took its toll on Monte Cristo. When word of a gold rush along the Klondike River in Yukon, Canada, broke in July 1897, workers began slipping away, and by 1900 most of them had joined the estimated 100,000 miners who'd headed north.

In 1903 Northern Pacific acquired the Monte Cristo railroad's right-of-way, the town dwindled away, and the once-booming mining operations fully ceased by 1907. Although W. O. Welch was among the earliest luthiers in the Pacific Northwest -- joining a short list including Seattle's Otto Anderson (1837-1938), Port Townsend's Chris J. Knutsen (1862-1930), Tacoma's John Hegberg, and Portland's Frank Coulter (1862-1940) -- none of his musical instruments are known to have survived. Monte Cristo remains a popular "ghost town" destination, still enjoyed by day hikers today.