Prior to the building of reliable overland roads and railroads, river travel was the primary method of transporting goods and people in the White River Valley. The indigenous Coast Salish people used canoes on the river, and later settlers would build barge-like scows. In the 1850s, the Traveler became the first steam-powered boat to travel up the Duwamish to the White River, ushering in a new era of steam-powered boat travel that expanded the social and economic worlds of White River residents by better connecting them to the larger population centers of Seattle, Tacoma, and Fort Nisqually. Steamboat traffic on the White River stopped in the late 1880s, but not before it had shaped settlement patterns, created new wealth, and left a legacy of nautical place names up and down the Valley.

River Transportation Before Steamboats

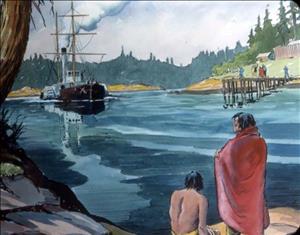

The first peoples of the White River Valley were Coast Salish families who used the rivers as their main highway and source of identity. Waterways were so important, many tribes in the area identified themselves as "the people of…" their home river or stream basin. Carving canoes from huge cedar trunks, they used these versatile vessels to travel long distances, transport goods, gather food, and visit distant relations. Shallow shovel-nosed river canoes allowed trade and life to continue as normal even when the White and Green rivers were going through their regular periods of flooding.

The earliest non-Native settlers in the area also lived near the rivers. Settlers along the Duwamish and White River waterways in the 1850s were farmers, aiming to clear the land and cultivate crops. The budding towns of Fort Nisqually, Tacoma, and Seattle were the marketplaces at the end of their river highways.

Most settlers were unfamiliar with river travel and tried to make overland roads and trails, but they were regularly stymied by mud and flooding. Land travel from the Valley to Seattle took 10 days by ox team and required fording six river crossings. To avoid this lengthy trip, settlers regularly paid Native people with canoes to transport White River farm families and their goods up and down the River. Canoes were sometimes paired up and crossed with planks lashed between them -- catamaran style -- to carry bulky cargo.

Settlers devised river craft of their own for runs to marketplaces and waterfront logging camps. As much barge as boat, these flat-bottomed "scows" were propelled by the river current, sometimes aided by long poles or sweeps. The downstream ride was relatively easy compared to the return trip against the current. Scow operators used poles or hired horse teams to tow their craft upstream. Patrick Hayes is credited with operating the first scow on the White River in the early 1860s. Scows attached to heavy-duty cables were also used as ferries at river crossings prior to permanent bridges being built.

The frequency of scow traffic on the White River gave birth to a series of boat landings at strategic farms fronting the river. Some landings were little more than plank wharves jutting from the shore, but they made loading and unloading boats immeasurably easier. Landings were named for the farmers who developed them. The principle White River landing places became Van Doren's Landing, located in what is today northwest Kent, and Alvord's Landing, south Kent today. Alvord's Landing was outfitted with a larger dock and a locked warehouse where neighbors could store their goods until the next scow trip, for a fee, making the landing a profitable venture for both the Alvord family and the ship captains who would soon dock there. Other large landing owners set up small stores and purchased general goods through boat captains that could be resold to their landlocked neighbors, making them some of the first retailers in the valley.

Steamboats in the Puget Sound

Steamboats were in use in the Puget Sound region as early as the 1830s, though it would take several decades before they reached the White River Valley area. The ponderous side-wheeler Beaver had been a workhorse for the British Hudson's Bay Company since 1836, paddling to and from Fort Nisqually as the first steamboat on the Pacific Ocean. In 1853, the Beaver was finally joined by the Otter. These early steamboats were built in England, sailed across the Atlantic, then had their steam components added once they arrived in the Americas.

Steamboats were smaller than their steamship counterparts, and generally intended for use on calmer waters such as lakes, rivers, and protected harbors like those found in the Salish Sea. Like their larger cousins, steamboats used steam power to spin one or more large paddlewheels which in turn paddled the steamboat. Side-wheelers had one or two wheels located in the middle of the boat; sternwheelers had a single large wheel attached to the rear of the boat. Propeller boats, also called screw steamers, used steam power to turn large metal propellers under the waterline, and were also considered part of the region's steam fleet despite their lack of the traditional visible paddlewheel.

River travel by steamboat started once there was enough economic incentive to justify the costs in time, fuel, and potential damage to the boats. The Traveler, a sleek, 85-foot-long iron propeller boat, had been built in Philadelphia and brought to Puget Sound by way of Cape Horn and San Francisco. Its owner and captain, John G. Parker, began running the Traveler on the Olympia-Steilacoom-Seattle mail route in 1855.

Steamboats Come to the White River Valley

The Traveler was soon elected for new kinds of service. Chartered by the Territorial Adjunct General, Captain Parker's Traveler carried arms and soldiers where needed. One of its early missions (in November 1855) was to transport Captain C. C. Hewitt's Company "H" volunteers up the Duwamish River from Seattle, with six large canoes in tow. The troops were heading to their assigned post at the junction of the White and Green rivers, but the Traveler could navigate no farther than the mouth of the Black River.

In April 1856, the Traveler ascended the same route to Fort Dent on the Black River and continued on to Fort Thomas, located at the border between Kent and Auburn today. The White River had finally been breached by steamboat. The Traveler was also the first steamer on the Snohomish and Nooksack Rivers.

The steamboat era on White River soon began in earnest. Shallower than today and unimpeded by levee improvements, the River was full of bends and sandbars. It flooded frequently in wet-weather seasons, hurling massive logs downstream and hiding them in its depths, creating treacherous snags and jams. A boat on the River could not be too big, or have too round a hull, or too deep a draft below the water's surface. And whatever propelled it could not be apt to catch snags. This gave preference to steamboats with stern-mounted paddlewheels and very flat bottoms. Boats with the right construction could sail through portions of the river as shallow as 18 inches.

River Traffic Increases

Seeing a growing potential in the Duwamish River and White River trade, Seattle scow and steamboat operator John S. Hill built a small sternwheeler specifically for the route named Gem. For several years the Gem maintained erratic service on the White River route, and was occasionally chartered for special excursions -- like a June 1868 "camp meeting" conducted "on the banks of the [White] River near Brannan's schoolhouse" (then located in today's southwest Kent, near West Valley Highway).

But the Gem was a round-bottomed boat, unable to ply the White in low-water seasons. In 1866, Captain Hill converted his Black Diamond, a flat-bottomed schooner (sailing scow) into a sternwheeler. The Black Diamond did fine on the White River and logging camp routes, but even Captain Hill seemed to lack confidence in its abilities on the open water. When it made rare trips between Seattle and Olympia, he was known to go around town bidding farewells to everyone he knew.

In 1871, a new entry joined the growing competition for the White River transportation trade. Captain Simon Peter Randolph had been active in boating on the Duwamish and Black rivers and Lake Washington since 1868, and was responsible for dredging much of the lower White River, clearing it of many logs and snags. He devised a unique new way to construct the relatively flat hull upside down. When it was finished and rolled to the water, he used heavy rocks to lower one side of the hull as the tide came in, then employed the outgoing tide to flip the hull over -- right side up.

Once its engines, stern wheel, and tall deckhouse were installed, the Comet was in commission. The Comet was considered the most successful steamboat on the White River. It could reach Alvord's Landing above Kent at virtually any water level. Captain Randolph later built the stern-wheeler Edith R. for the White River trade as well.

The mid-1870s and early 1880s were the heyday of steam-boating on the river, and also the beginning of the hop-growing boom in the valley. Some five or six boats, all sternwheelers, simultaneously ran the route, transporting both farm goods and heavier materials like machinery and construction supplies. Farmers could also sell timber from their land to steamboat captains -- steamboat boilers burned massive amounts of wood, which increased the demand for cut firewood up and down the River. (The early steamboat Beaver is described as burning 40 cords of firewood a day during normal operations.) Among the newcomers were craft named Wenat, Nellie, Lily, and Lanny Lake (and later, the Daisy, Glide, Rose, and Gazelle). When they were empty of cargo, the boats were often leased for special events such as meetings, weddings, and parties, becoming anchored, floating community halls.

The boats would take around 12 to 14 hours to churn upriver from Seattle to Alvord's Landing -- a far cry from the four-day trips required when traveling by scow. They could sometimes push farther to Brannan's farm, located in what is today northeast Auburn, but only in the highest water. It was impossible to turn the boats around in the river, so they usually backed down the river stern first, dragging heavy lengths of chain behind their rudderless bows to stay centered in the channel. They still got stuck from time to time. People on shore helped break them free with towropes, or they would simply wait for the river to rise enough to let the boat float free.

Steamboat Captains Become Local Figures

Puget Sound maritime historian Gordon Newell gave this description of a riverboat captain's stature in the mid-nineteenth century:

"Deep-water skippers are seldom at home, and so take little part in the affairs of their communities, but the American river captains had long been counted among the most distinguished citizens of their localities; the Puget Sound steamboat men followed the tradition. Their dignity was enhanced by impressive side-whiskers ... handlebar mustaches, at the very least ... blue serge, brass buttons and, when ashore, high silk hats. To the small-fry of the Puget Sound Country they took the place of modern jet pilots, locomotive engineers, and racing car drivers, with a dash of Hopalong Cassidy thrown in" (Ships of the Inland Sea ...).

Steamboat crews were generally more affable than efficient in following their trade. When boat whistles blew, White River folks gathered at the landings to welcome them and see what news, mail, goods, and newcomers had arrived. As they picked up produce for the markets, captains were often given lists of items to shop for in Seattle and bring back on their next excursion.

The boats stopped almost on demand. One anecdote related by historian Clarence Bagley regards Captain Charles G. True, then skipper of the Comet. He was heading downstream with his cargo when a White River farmwife ran to the riverbank and yelled, "Stop! I have a large lot of eggs to send to Seattle, but need one more egg to fill the last dozen. Will you wait?"

"Certainly, madam," responded Captain True, "but please hurry up the hen!" Forty-five minutes later, the hen delivered and the Comet resumed its trip.

A local romanticized hero among the captains was James Jeremiah Crow. Raised in Oregon's Willamette Valley, 20-year-old Crow was at school in Seattle in 1862 when he met and eloped with Emma Russell, 17-year-old daughter of White River homesteaders Samuel and Jane Russell. The couple rowed a canoe up White River to her parents' homestead in what is today southern Kent, where they resided for several years.

They took up their own homestead in 1867 and went on to have 13 children. Crow planted one of the early hops fields in the valley and engaged in other business pursuits. Hops made him (and many of his neighbors) rich. With their wealth, the Crows built a magnificent Kent mansion. In 1883, James Crow bought the sternwheeler Lily and earned his pilot's credentials. He operated the Lily first on the White River and later on Puget Sound for four years.

End of the Steamboat Era

By 1887 railroad construction through the Valley had made the steamboat trade obsolete. The last skipper to bring a steamer up the White River was Captain Brooks Randolph, son of local steamboat pioneer S. P. Randolph. His Edith R. hauled loads of railroad iron to rail construction sites, ushering in the new era of transportation. Captain Crow docked the Lily at Alvord's Landing, where it eventually rotted and sank.

In 1976, a century after the heyday of steamboats in the White River Valley, members of the Citizens Band for Common Courtesy set concrete and bronze historical markings along the river at the location of Alvord and Van Doren's Landings. These markers stood for a few decades, but due to construction and vandalism were removed by the Greater Kent Historical Society & Museum and reinstalled on the museum's grounds in 2018.