On April 23, 1899, two ships collide in the early morning darkness on Commencement Bay. The Glenogle is a 400-foot ocean liner bound for Asia. The City of Kingston is a 246-foot day liner on its usual route from Victoria, British Columbia to Tacoma. In this original essay, Tacoma historian and preservationist Michael Sullivan describes the fateful mistakes leading to the crash, and the ensuing mayhem.

Warning Bells

In the predawn hours of April 23, 1899, Howard Corwin was shooting wharf rats at the Pyramid Flour grain elevator on the Tacoma waterfront, where he worked as a nightwatchman. The waterfront was getting a slow start on a sleepy Sunday morning as Corwin looked up from his gun sight long enough to watch the 400-foot British steamship Glenogle pull away from the Northern Pacific dock. The steel-hulled, blue-water ocean liner was headed to Asia in the days when several passenger ships a week arrived and departed from the rail head at Tacoma destined for Manila, Yokohama, and Shanghai. He watched the smoke plume rise and begin trailing from the main stack as the vessel sailed by, picking up speed across Commencement Bay headed for Browns Point.

In the half light just before 4 a.m. his sharp eye caught the silhouette of another, smaller vessel headed across the bay through a light fog, showing only running lights. In the few minutes that followed the watchman began hearing a series of signal bells and then warning sirens from both ships. Something was wrong.

Luxury on the City of Kingston

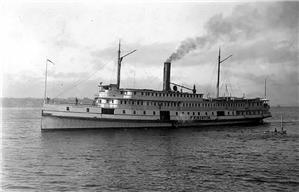

The City of Kingston was a Hudson River day liner built in Wilmington, Delaware and launched in 1884. In 1889, the elegant, 246-foot-long steamship was sold to the Puget Sound and Alaska Steamship Company (PS&A), which brought her from New York on a two-month voyage through the Straights of Magellan, into the Pacific Ocean, and on to Puget Sound just as Washington was becoming a state and Tacoma was reaching full-fledged boom velocity.

In building the City of Kingston, the Harlan & Hollingsworth shipyard crafted three decks of mahogany paneled salons, modern incandescent lights, hand-carved furniture, and staterooms for 300 overnight passengers. The heavy 1,400-horsepower steam engine and boilers were tucked deep into a steel hull that isolated the rumble and propeller vibration from the smooth-riding passenger decks above.

The PS&A steamship company was aligned with the powerful Northern Pacific Railroad, and they placed the new luxury liner on the daily route from Tacoma to Victoria, British Columbia, with stops in Seattle and the customs station at Port Townsend. The City of Kingston quickly beat out all maritime competitors on the prized international run, both for its fast, dependable service and for the unmatched on-board accommodations for up to 600 people. In the final days of the nineteenth century, on its own inland sea, the vessel was like a tiny Titanic.

Explosion in the Night

The Reverend Horace H. Clapham, rector at Tacoma's Trinity Church, was half awake in stateroom No. 41, amid-ship, starboard side on the upper middle deck of the City of Kingston. The upsound, Saturday trip the night before, on April 22, 1899, was crowded and noisy, but the ship was only part full and quiet as it returned to Tacoma in time for the clergyman to make morning services. The carefully handled stock of barreled Canadian whiskey and imported wine being brought to the restaurants and barrooms of Tacoma were the only unholy reminders of the previous voyage.

Gazing out his window at the familiar harbor lights of Tacoma, Clapham was puzzled as a dark shadow descended over his view. Then all hell broke loose. The outside wall of the stateroom exploded, spraying hardwood framing, glass, and metal splinters into the suddenly dark space. Something sharp slashed his forehead. He felt blood running down his face as he discovered he was hopelessly pinned under wreckage and shattered furniture. In a later account the clergyman said, "I was certain then I had met death and resigned myself to God."

Anatomy of a Shipwreck

The series of events that immediately preceded Rev. Clapham's encounter with his God would be controversial and intentionally obscured in the days and months that followed. Inquests and court proceedings would explore every decision that was made and analyze every condition of weather, human behavior, and maritime law. Among the known facts of that morning, however, is that the good reverend was an actor in one of Tacoma's most dramatic maritime disasters.

On that Sunday morning, the incoming City of Kingston rounded the lighthouse at Browns Point and fell almost immediately into a dead-on course with the larger steamship Glenogle, which had just cast off from the Northern Pacific Wharf. Headed for the same dock, pilot John Brandow steered the City of Kingston through a light fog bank and called down by voice tube for engineer W. S. Everett to reduce speed as they crossed the bay. Then Brandow spotted the Glenogle emerging from the fog, signaled his intentions to pass on his starboard, and called for all stop below.

Both ships began using bell signals to communicate their respective courses as the smaller City of Kingston chose to cross the larger ship's path, Brandow assuming that the Glenogle would steer north out of the harbor. A painfully long, slow choreography of unintended consequences began to play out over the next few minutes as a multitude of small decisions on both vessels grew into a major maritime mistake. With no headway (in fact the engines were in reverse) the City of Kingston lost steering and came to a full stop directly in the larger ship's course, while Captain Frank Gatter of the Glenogle found he could not slow his fully loaded and coaled steamer as it was pushed by the outgoing tide and flow of the Puyallup River.

Both Captains had time to warn their crews that a collision was coming as piercing, unmistakable warning signals and steam whistles began blaring from both vessels. At 4:10 a.m. the knife-edge bow of the massive Glenogle sliced deep into the City of Kingston at about a 45-degree angle. The deafening sound of the collision carried all the way to Old Town. Before escaping the engine room, Chief Engineer Everett witnessed the massive hull cutting directly into the boilers of the City of Kingston. Steam and jets of seawater began flooding the engine room. The two ships were locked together by the impact.

The jolt to both vessels threw crew and passengers off their feet and immediately woke the people still in their bunks. On the main deck of the Glenogle, crewmen began throwing lines down to the smaller, severely heeled-over City of Kingston as people poured out onto her decks in bedclothes and blankets. Philippine crew members dove into the water to pull out several panicked passengers and lifeboats on both vessels were lowered.

Then a completely unexpected and terrifying noise rose from the City of Kingston, and just 10 minutes after the collision the stern section began sinking fast -- sucking down with it the rear staterooms and deck. In the moments that followed the Glenogle slipped back and out from the gaping wound in the side of the City of Kingston and it looked like the damaged ship was about to snap in two. Instead, the heavy steel hull, with its ruptured boilers and disabled engine, tore away from the wood superstructure and sank like a anchor.

Astonishingly, the entire upper, three-deck section of the City of Kingston, with all passengers and crew, was still afloat and stable as a log raft.

Rescue Efforts

Now the harbor was awake. The Gig Harbor passenger steamer Victor changed course and pulled up next to the Glenogle, followed by the steam tug Favorite. Gangplanks were rigged so that some passengers simply walked to safety on the big British liner. Once the the Glenogle was found not to be in danger of sinking, it returned to the Northern Pacific dock with passengers from both ships. By daylight, the still-floating section of the City of Kingston was towed to the shore near Old Town and the grim task of determining causalities began.

Miraculously, Reverend Clapham was freed from the wreckage when the hull dropped away from the upper decks. He had time to pick up his satchel and bible before walking away from the experience without even getting wet. In fact, once everyone was counted, passengers and crew, there were no deaths or serious injuries in the most storied shipwreck in Commencement Bay's history.

In the April 25, 1899 issue of the Tacoma Daily Ledger, pages of details about the collision were published along with a colorful variety of stories and personal accounts. A special note was printed about the fate of the Canadian spirits, which had been washing up along the beach at Old Town. Customs officials and police officers were troubled by the fact that only one barrel of whiskey and a few bottles had been recovered from a large shipment of spirits shown in the City of Kingston's bill of lading. The officials referred to the mysteriously disappeared liquor as an illegal casualty of the wreck, lost to the wharf rats.