Five years before the 18th Amendment kicked off national Prohibition, Washington voters approved a state initiative banning the sale and manufacture of alcohol. Within days of this new state law, a thriving black market emerged to satisfy the sudden demand for illicit liquor. In the waters of Puget Sound, an active fleet of rum-running boats -- often powered by Boeing airplane engines -- smuggled liquor from Canada, through the Strait of Juan de Fuca, and to ports throughout Western Washington. From there, the contraband would be distributed by area bootleggers. Perhaps surprisingly, these local liquor men were known for their integrity and genteel ways, as well as their general disdain for violence. In Tacoma, the top trafficker of booze was Pete Marinoff, though everyone knew him as "Legitimate Pete." The Seattle market was run by the "King of the Puget Sound Bootleggers," Roy Olmstead, a former police lieutenant who became the area's top bootlegger. In the corridor between the two cities, restaurateur Frank Gatt set up a giant moonshining operation to satisfy the thirst of nearby residents. This rise in bootlegging invited an aggressive response from the law. Federal Prohibition agents became known for their pugnacious tactics, often using a "shoot first, ask questions later" approach to apprehending bootleggers. Out on the water, a fleet of Coast Guard cutters, armed with machine guns and cannons, remained vigilant for suspicious boats. This historical era, marked by decadent soirees, militant police raids, and late-night shootouts on local waterways, lasted nearly 20 years, until the national repeal of Prohibition in 1933.

The Early Years

On November 3, 1914, Washington state residents headed to the polls in record numbers to vote on State Initiative 3. The initiative, which would make the manufacture and sale of alcohol illegal, had been drafted and spearheaded by local temperance groups in response to the vice that had proliferated throughout the state at the turn of the century. The controversial initiative won by a slim margin, effectively transforming Washington into a dry state.

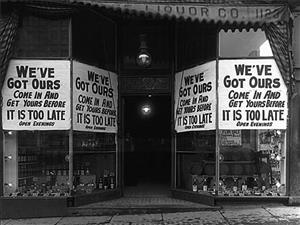

When this new law went into effect on January 1, 1916, state residents could still consume alcohol, but a legal permit was required to import it from out-of-state vendors. Quantity was limited to either a half gallon of hard liquor or a case of beer (24 cans) per month. Alcohol could also be obtained with a valid medical prescription, prompting the opening of hundreds of new pharmacies. Eventually, the right to buy out-of-state alcohol was removed as a legal privilege, thus establishing Washington as a truly dry state. A black market quickly opened up, paving the way for the first wave of area bootleggers.

In the Puget Sound region, the underground market for alcohol was controlled by two rival gangs. One of these crews was headed by Edward Jack Margett (sometimes spelled Marquett), a former Seattle patrolman who was otherwise known as "Pirate Jack" due to his penchant for hijacking rum-running ships and then selling the stolen alcohol from his Seattle headquarters. Battling Margett for control of the local booze market was a squad of bootleggers headed by brothers Logan and Fred Billingsley. When Washington went dry in 1916, the Billingsleys opened the Stewart Street Pharmacy to cash in on the sudden demand for medicinal liquor. They were eventually forced to close their pharmacy after receiving too many citations for various liquor violations. Typically, such citations involved the sale of black-market alcohol or selling to people without a valid prescription. Undeterred, the Billingsleys set up a large-sale moonshining operation in a warehouse on Seattle's Westlake Avenue and began manufacturing their own booze.

In response, Margett began hijacking deliveries of Billingsley's liquor, which set up a tense standoff between the two groups. In one of the more heated moments, the two gangs exchanged early morning gunfire after trying to claim the same shipment of liquor in an empty parking garage. The feud finally came to a head in the summer of 1916. Fearing further strikes by Margett, the Billingsleys hired an armed security guard to keep watch over their warehouse. On the night of July 24, 1916, two Seattle police officers were out patrolling their beat when the Billingsleys' watchmen mistook them for Margett's men and opened fire, resulting in a shootout that left the officers dead. An investigation into the shooting revealed the true purpose of warehouse, and the Billingsley brothers were promptly arrested. Soon after, Margett was arrested on charges of grand larceny and "accepting the earnings of unfortunate women," thus allowing for a brief lull in the local vice trade.

At Seattle City Hall, Hiram Gill was serving his second term as Seattle mayor. He had previously been removed from that office following a corruption scandal after it was revealed that he had permitted the opening of a 500-room brothel -- reportedly the largest such establishment in the world. Against all political odds, Gill managed to get re-elected after presenting himself as a reformed, law-and-order candidate. With the fall elections around the corner, Gill used the arrests of Margett and the Billingsleys as proof of his tough stance on crime, and he was elected mayor for a third time in November 1916. Despite publically promoting himself as a virtuous politician, Gill was soon back to his old ways, running a payoff system in which virtually anything was allowed for the right amount of money. Things got so bad that the army base at Fort Lewis declared the entire city off-limits to its soldiers after many of them were taken out of service due to venereal disease.

The Billingsleys' trial was underway where it was directly revealed that Gill had accepted $4,000 in bribes from the two brothers, leading to yet another bruising political scandal for the mayor. The Billingsleys were found guilty and sentenced to McNeil Island Penitentiary just as Gill served his final, scandal-plagued months in office. Gill died a few months later on January 7, 1919, just as national Prohibition was about to take effect. This new national law was much stricter than Washington state prohibition had ever been. It would usher in a new era in the region's Prohibition saga.

Rise of the Gentlemen Bootleggers

The biggest change revolved around Canada's emerging role in the booze trade. Prior to national Prohibition, bootleggers in dry states would simply purchase wholesale quantities of alcohol in wet states, smuggle it over state lines, and resell it for marked-up prices. Following passage of the 18th Amendment, however, there were no more wet states, and Canada emerged as the logical source for large quantities of alcohol, especially for states along the northern border of the United States.

In the Puget Sound region, rum-running ships would journey to Canadian port cities, such as Vancouver or Victoria, load their hulls with wholesale quantities of top-shelf liquor and then smuggle the illicit freight down the Strait of Juan de Fuca to various drop-off points along the stretch from Bellingham to Tacoma. In the early days of Prohibition, capture was easy to avoid as maritime enforcement belonged to a small fleet of outdated Coast Guard ships. Out of necessity, the Coast Guard quickly began updating its fleet with newer and faster cutters, which boasted long-range cannons and powerful machine guns. These weaponized Coast Guard ships were rarely hesitant to open fire on suspicious boats. They soon became highly feared by Puget Sound rumrunners. Another Coast Guard tactic was to chase suspected rumrunning ships toward bays and coves, trying to trap them inside for easy capture. In response, smugglers began installing powerful airplane engines on their boats. At the time, nearby Boeing Airfield was full of surplus aircraft leftover from World War I, and parts could be purchased for cheap. Innovative rumrunners would strip V-12 engines from decommissioned combat planes and use them to power their ships. These powerful smuggling ships soon became known as "fire boats," named not only for their fast speeds and loud engines, but also for their cargo of "firewater."

Most rumrunners acted as independent contractors for hire, smuggling shipments of booze for wealthy customers. Others worked as part of a crew for a specific bootlegger. Typically, Puget Sound rumrunners would operate at night, when it was more difficult to be spotted. Many would limit their smuggling to stormy weather, when Coast Guard ships were least likely to be out on patrol. This made their profession a particularly hazardous one, thanks to submerged logs throughout Puget Sound that could easily decimate a ship upon impact.

Another hazard was the threat of piracy, as several active pirate ships were known to patrol local waters, looking to relieve rumrunning ships of their cargo. Overall, though, rumrunning provided an easy way to make large amounts of money for any would-be risk taker with a fast enough boat. The most famous of these Puget Sound rumrunners was Johnny Schnarr, a World War I army veteran who grew up in Chehalis, Washington, and became the region's most successful rumrunner, having made more than 1,000 deliveries. He held the distinction of being one of the only rumrunners to have never been caught, even after having a $25,000 reward offered for his capture. Schnarr's reputation placed his services in high demand, and he hauled liquor for many of the region's top bootleggers.

The top supplier for all this black market alcohol was a quasi-legal Canadian export conglomerate known as Consolidated Exporters. Taking advantage of the American demand during Prohibition, Consolidated Exporters set up liquor warehouses in various British Columbia ports, creating a convenient way for Washington smugglers to load up their boats. Secret offices were also established by Consolidated Exporters in Olympia, Tacoma, and Seattle, offering a place where bootleggers could discreetly place orders that would then be picked up by their smuggling ships in Victoria or Vancouver. This provided a robust trade in smuggled booze, and the Puget Sound region was soon awash in Canadian liquor. When Canadian authorities finally caved to American political pressure, and prohibited the sale of alcohol from any of their ports, Consolidated Exporters simply purchased several freighter ships, loaded them with crates of alcohol, and anchored them in the Haro Straits. These floating warehouses, known as "motherships," would sit anchored in Canadian waters, waiting for American rumrunners, who would arrive at assigned times to pick up their orders.

Kings of the Booze Business

One of Consolidated Exporters' biggest customers was a former Seattle police lieutenant-turned-bootlegger, Roy Olmstead. Olmstead had been dismissed from the police force in 1920 after his arrest at Meadowdale Beach in one of the largest liquor busts in Washington state history. Immediately afterward, Olmstead turned to bootlegging as a fulltime career, eventually becoming known as "The King of the Puget Sound Bootleggers." At one point, his operation was so successful that he became one of the area's largest employers, with a giant workforce of clerks, lawyers, dispatchers, rumrunners, drivers, and mechanics.

His experience as a Seattle police officer certainly helped his standing as the area's kingpin -- he knew which officers could be paid off and which could not. He knew their schedules and how they conducted their operations, which gave him the upper hand in avoiding arrest. He also used D'Arcy Island (part of the San Juan archipelago) as the primary drop-off point for his smuggling operation. At the time, D'Arcy Island was home to a leper colony, so visitors to the island were infrequent. This gave Olmstead a unique geographic advantage. Even more important to his success, Olmstead devised a scheme to avoid paying Canadian export taxes, thereby allowing him to sell liquor at lower prices than his competitors. Lastly, Olmstead enlisted the help of Al Hubbard, a Seattle whiz kid who had recently made headlines with his invention of the "atmospheric power generator," a mysterious engine that allegedly drew electricity from the air. Olmstead was able to rely on Hubbard's technological prowess to maintain his fleet of ships and vehicles, as well as install them with state-of-the-art communication devices to help steer clear of the Coast Guard. Hubbard also constructed one of Seattle's first radio stations for the bootlegger, which Olmstead operated from his mansion in the Mount Baker neighborhood. Urban legend holds that this radio station, KFQX, was used to assist Olmstead's liquor operation. With all of this at his disposal, Olmstead was able to monopolize the Seattle black market until his incarceration in 1927.

In Tacoma, the top bootlegger was Pete Marinoff. He had been given the nickname "Legitimate Pete" due to his avoidance of other criminal enterprises such as prostitution, narcotics, and gambling. Considered to be one of the region's shrewdest bootleggers, Marinoff maintained a fleet of seven speedboats that he used to smuggle Canadian liquor into the Tacoma market. In the early days, Marinoff would often pilot his own ships; he later formed a partnership with Johnny Schnarr in which the ace rumrunner served as his top smuggler.

In South Seattle, Frank Gatt became known for his top-quality moonshine. Prior to statewide Prohibition, Gatt was a successful saloon owner who had lost his means to earn a living when Washington voted to go dry. He decided to remain in the alcohol industry by manufacturing his own, setting up large-scale distilleries in the rural farmlands of north Seattle. Gatt would lease barns from dairy farms, using them as space for setting up his enormous moonshine stills. Gatt's rural locations were unlikely to be discovered, and the smell from the cattle farms would offset strong odors often created by the distillation process. It was a clever way to avoid detection by the authorities. Gatt opened up a few small restaurants in downtown Seattle that he used as fronts for selling his popular brand of moonshine. He became one of the area's top liquor men, satisfying the market from South Seattle to Federal Way. The black market in Aberdeen was similarly controlled by moonshine kingpin Chris Curtis.

The Good Guys?

The region's bootleggers would often work together, sometimes splitting liquor deliveries or sharing parts of their crews. Overall, they respected each other's territories and conflict was infrequent, with very few incidents of violence. Their shared enemy was federal Prohibition agents, which probably helped encourage this level of partisanship. Overall, many of the Puget Sound liquor bosses were known for their gentlemanly ways. This was perhaps best embodied by Olmstead, dubbed "The Gentleman Bootlegger" for his ethical rules of conduct. Olmstead was still a Seattle police officer in the early days of Prohibition, and after witnessing senseless violence perpetuated by such outfits as the Billingsleys and Margett, decided to operate in a different manner. His No. 1 rule was that his men could not carry guns or engage in violence. To his way of thinking, this only invited unwanted trouble, which could be just as easily avoided by paying people off. In addition, Olmstead sold only premium bonded liquor that he smuggled from Canada, as he wanted to provide alcohol that was both safe to drink and untainted by other criminal activity. On a personal level, Olmstead was approachable, always willing to stop on the street for a photograph or engage in conversation with an admirer. He became a folk hero to some in the region.

Other local bootleggers held similar reputations. Pete Marinoff was "Legitimate Pete" because he engaged only in bootlegging, which at the time was widely viewed as an honorable profession. In South Seattle, Frank Gatt was known for his philanthropic ways and willingness to help locals in need. These Pacific Northwest bootleggers were markedly different than their eastern counterparts; there were no gun battles over turf, nor massacres like those seen in New York, Chicago, and St. Louis. Bootleggers in the Puget Sound region tended to approach the trade as entrepreneurs rather than mobsters. This level of civility was on display in March 1922, when a bootleggers convention was held at a Seattle hotel. Utilizing Robert's Rules of Order, more than 100 bootleggers formally established rules and protocols for their profession, and then celebrated together afterward.

Final Days

Upon the onset of national Prohibition, the Bureau of Prohibition was established in the interest of enforcing these new liquor laws, with federal offices in each of the U.S. states. The two men tasked with running the Washington state branch from a downtown Seattle office building were Director Roy Lyle and Assistant Director William Whitney. Lyle was known for being more quiet and reserved; he tended to focus his efforts on the administrative duties of the job. This left Whitney in charge of commanding their team of "dry agents." With the belief that strong-armed tactics yielded the best results, Whitney set out to form a team of aggressive enforcers and specifically selected men known for having brutish personalities. If a business or private residence was suspected of engaging in the distribution of illegal booze, Whitney and his agents would drag the suspects out after smashing their front door down with sledgehammers. When asked about accusations of police brutality, Whitney dismissed them by stating, "no bootlegger gets rough treatment unless he deserves it."

It didn't take Whitney long to begin focusing his efforts on the area's two biggest moonshiners, Roy Olmstead and Frank Gatt. Olmstead proved to be particularly elusive because he had so many people on his payroll. Whitney was never able to catch him in the act. Out of desperation, Whitney began wiretapping Olmstead's phone lines, which gave him valuable insight into how the bootlegger was conducting his operation. From this, Whitney was able to obtain a search warrant, and on the evening of November 17, 1924, Whitney and a team of agents raided Olmstead's house. While they found no liquor, Whitney and his team ransacked Olmstead's home until discovering incriminating documents and business records that proved to be even more valuable. Together with the phone records, Whitney used these seized documents to secure a federal grand jury indictment against Olmstead and his associates.

At the same time, Whiney and his agents were conducting surveillance on Gatt's operation, trying to locate his stills. Their eventual breakthrough came from a disgruntled ex-employee of Gatt's who reported the details of Gatt's operation to the feds, leading to an immediate raid at his restaurant headquarters, the Monte Carlo. Gatt was arrested on the spot and would later plead guilty to his crimes. Both he and Olmstead were imprisoned at McNeil Island Penitentiary, Olmstead from 1927 through 1931, and Gatt from 1927 through 1929.

With two of his biggest competitors behind bars, Tacoma's Peter Marinoff was able to increase his share of the liquor trade, with Johnny Schnarr now serving as his top rumrunner. By this time, Canada had introduced new shipping laws mandating that any Canadian ship carrying alcohol had to stay at least 40 miles off the U.S. coast. Consolidated Exports was forced to relocate its freighters from the Haro Strait to the open waters of the Pacific Ocean. For rumrunners, this added a new level of difficulty, as ocean-faring ships were now required for picking up orders. Schnarr built such a ship with Marinoff's financial backing, helping cement their control over the local booze trade. In Seattle, no single person emerged to take over Olmstead's previous role as the city's kingpin; rather, control shifted between various marginal-level bootlegging syndicates.

National Prohibition officially ended when the Twenty-First Amendment was adopted on December 5, 1933. While alcohol was once again legal, the lives of many were profoundly changed. After their release from jail, the Billingsley brothers moved to New York City, where Logan established himself as a civic leader, serving as president of the Bronx Chamber of Commerce and helping to secure New York City as the site of the 1939 New York World's Fair.

Jack Margett re-established himself in Northern California, serving as the manager of a housing organization until finding himself at the center of a pension scam. Roy Olmstead dedicated himself to the Christian Science religion, which he had converted to during his time in prison. He avoided all criminal activity, and spent the remainder of his years helping to rehabilitate ex-convicts so they could live productive lives. The radio station he started in 1924 was eventually sold to Seattle businessman Birt Fisher and operates today as KOMO radio and television.

Frank Gatt followed a less redemptive arc. He was sent back to prison in 1935 after IRS agents raided an illegal still he was operating in Renton and arrested him for tax evasion. Following his release, Gatt was finally able to avoid any other criminal activity and spent his remaining years working as a home contractor, helping to repair homes in his Beacon Hill neighborhood. Meanwhile, Pete Marinoff opened the Northwest Brewing Company in an old Tacoma meatpacking plant. It was a successful brewery until a union strike left one of Marinoff's delivery drivers dead. The resulting litigation forced him out of business in 1935. Afterward, Marinoff moved to California and became an insurance executive.

Consolidated Exporters was put out of business as soon as Prohibition was repealed in 1933. Its remaining fleet of "mother ships" was eventually auctioned off and used as logging ships. Many of the Puget Sound rumrunners returned to their previous maritime jobs as merchant marines or longshoremen.

Johnny Schnarr spent the rest of his years working as a commercial fisherman. The various rumrunning ships he piloted still serve as innovative examples in today's modern speedboat industry. It has often been speculated that hydroplanes evolved from these local smuggling ships, which had been modified with airplane engines, and it is no coincidence that locations where rumrunning was prevalent (Detroit, Seattle, and Florida) have since become popular hubs for hydroplane racing. In Seattle, such races are held every year as part of the Seafair Festival. Started in 1950, the annual festival serves as a nod to a time when "fireboats" dotted the Puget Sound and bootleggers quenched the region's thirst for black market booze.