Scottish-born B. Marcus Priteca (1889-1971) arrived in Seattle around the time of the 1909 Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition. An architect specializing in classical design, a chance encounter with vaudeville magnate Alexander Pantages (1876-1936) led to his first major project, a Pantages venue in San Francisco. It was the beginning of a fruitful partnership -- one that lasted almost two decades and firmly established Priteca as America's foremost theater architect. In addition to theatre designs such as Seattle's Coliseum, Orpheum, Paramount, and Admiral theaters, Priteca also lent his design expertise to the Congregation Bikur Cholim Synagogue, the Jewish House Educational Center, Longacres Racetrack, and the 1962 conversion of the Civic Auditorium into the Seattle Center Opera House. Priteca was named a fellow by the American Institute of Architects in 1951, and continued his design work in Seattle up to his death in 1971, outlasting many of the magnificent structures for which he was responsible.

Early Years

B. Marcus Priteca was born in Glasgow, Scotland, on December 23, 1889, the son of Charles and Diana Priteca. Charles, a successful lawyer, provided his children with a privileged upbringing in Edinburgh, where the family eventually settled. Much of Priteca's early schooling was done privately, with studies that emphasized a classical education and the arts.

By 1904 Priteca, already inspired by the buildings around him, was completing coursework at George Watson College and beginning a five-year apprenticeship under noted architect Robert McFarlane Cameron (1860-1920). He continued his studies while under Cameron, graduating from the University of Edinburgh in 1907 and the Royal College of Fine Arts in 1909 (Bagley, 443).

Priteca combined his architectural studies with an interest in the properties of sound; he was particularly fascinated by the acoustical research then being done by Wallace Sabine (1868-1919) of Harvard University. It was this interest in sound that would play a pivotal role in Priteca's architectural career.

Coming to Seattle

Just how, when, and why B. Marcus Priteca uprooted himself from Scotland is a confusing maze of stories. For example, a 1915 article in Town Crier (one of the first Northwest papers to feature him) notes that he arrived in Seattle through "patronage of the Crown," having been selected to study architecture abroad. It was after hearing the opinions of fellow students that Priteca and his family decided to travel there -- glowing reports that observed that Seattle was ripe for the construction of a monumental building (Town Crier). It's tempting to give credence to this version, given that it came only six years after Priteca's known arrival, but the Town Crier article is so flamboyantly written that its truthfulness must be called into question. The article also appeared near the completion of the Priteca-designed Coliseum Theater (1916), at 5th Avenue and Pike in Seattle, leaving one to believe that the writer may have been wearing a promotional hat when penning the account.

Another version, and by far the most popular story associated with Priteca's arrival, was his abiding interest in visiting the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific (A-Y-P) Exposition, the world's fair held in Seattle during the summer of 1909. Historian Clarence Bagley (1843-1932), writing in 1929, went as far as to provide the exact date: July 6, 1909, about five weeks after the exposition opened. According to this version, the A-Y-P, coupled with his ailing father's need for a warmer climate, prompted the family move from Scotland. If true, Priteca couldn't have embraced the city immediately: He was fond of recounting how he was arrested within hours of his arrival for violating a prohibition against smoking on a public street. And despite the fact that it was July, one wonders how Seattle's climate would have been such a vast improvement over Edinburgh's.

The variations in the story continued over the years. In 1965, Priteca told John J. Reddin of The Seattle Times that the trip started with a 1909 office discussion about a city named "Seetle," where the A-Y-P Exposition was to open later that year. A disagreement rose when Priteca's boss, Robert MacFarlane Cameron, argued that Seetle was up along the Yukon River, which Priteca knew wasn't true. An atlas was produced to settle the Seetle argument, but no one could locate the city -- someplace called Tacoma appeared on the map where Priteca thought Seetle was supposed to be. Confident of his geography, Priteca made a quick trip to a local steamship office where he was given a more detailed map, as well as some travel brochures (perhaps A-Y-P related?) showing "Seetle" and some if its newer buildings, such as St. James Cathedral and the White Building. "'I made up my mind that I would visit 'Seetle' and also see the results of the recent [1906] San Francisco earthquake,'" Priteca recalled (Reddin).

Priteca's colleagues teased him about his interest in such a rural city -- after all, the pictures clearly showed that "Seetle" still had overhead wiring. (This became a running joke for Priteca over the years: For as much as his architectural work changed Seattle's downtown, the offensive overhead wires were still there 60 years later.) The architect visited, and although Priteca had not intended to stay, he was immediately struck by the city. "I fell in love with [Seattle]," he recalled in 1965, "especially the excellence of the brick work and architecture, some of which still can be seen in older parts of the town" (Reddin).

Yet another story has Priteca first settling in Montreal before coming to the Pacific Northwest. And not even Priteca's death could put an end to the proliferation of stories -- one 1971 obituary claimed that Priteca lived in Vancouver before relocating farther south.

A Fateful Encounter

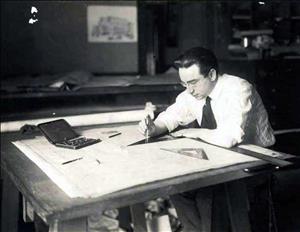

Once Priteca did arrive in Seattle, however, the facts of his life begin to fall into place. A friendship with local attorney Philip Tworoger led to Priteca's first job, as a draftsman for architect E. W. Houghton (1856-1927), who designed the Moore Theatre (1907) among other buildings. He didn't stay long; Priteca eventually left Houghton and joined a firm headed by W. Marbury Somervell (1872-1939), who had offices in the White Building.

It was likely that while in Somervell's employment, sometime in 1911, Priteca had an encounter with local vaudeville magnate Alexander Pantages -- a meeting that would change the young man's life forever. Priteca would spend the next two decades as Pantages's personal architect, expanding his own practice as Pantages expanded his circuit of popularly priced vaudeville houses throughout North America.

Six months before his death, Priteca recounted that Alexander Pantages was having acoustical trouble at his Portland venue, and summoned Priteca on the recommendation of others who knew of the architect's interest in acoustical properties. And here again, a possible discrepancy -- Jackie McDermott, writing in 1973, related a story in which Priteca had a chance encounter with Pantages while delivering some drawings to a Seattle architectural firm. In this version, the vaudeville manager was struck by the classical features in Priteca's work, which appealed to Pantages' own Greek heritage.

Regardless of how this first meeting actually occurred, by mid-1911 the 21-year-old Priteca had been hired to design his first house for the Pantages Vaudeville Circuit -- the Pantages in San Francisco, which opened on December 30, 1911. This was followed by a smaller Pantages venue (actually a scaled-back version of the San Francisco design) in nearby Oakland, which opened in August 1912. It was the beginning of a fruitful partnership, and many other projects followed over the years, taking Priteca as far east as Memphis and as far north as Winnipeg.

When designing houses for Alexander Pantages, Priteca often drew on classical and Renaissance architecture, building theaters into larger office complexes. The exteriors of these buildings were often done in brick or terra cotta, a building material that lent itself to various types of ornamentation. The interior details of the theaters were lavish, consistent with Alexander Pantages's desire to pull audiences out of their everyday lives and into a place of wealth and splendor.

The basic Pantages theater consisted of Roman columns on the sides of the proscenium arch, ivory and gold color schemes (these were Pantages' favorite colors), heavy drapes, and an ornamental drop curtain. The size could vary, but seating of 1,200 to 1,600 was typical, with side boxes and loge seating toward the front of the house; Priteca himself often planned the seating arrangement to maintain optimal sightlines throughout the house. ("Seeing is hearing," he once remarked to an interviewer. "Of course, a good ear doesn't hurt" [Duncan].) The auditorium itself often had contoured walls and ceilings, providing architectural detail and improving the venue's acoustics, and frequently employed ornamental domes as a centerpiece of the ceiling decoration. Pantages himself did not prefer formal lobbies, but Priteca incorporated them because rival vaudeville circuits put so much emphasis in this area. Stage lighting was often state-of-the-art in a Pantages house, but in other areas Priteca's designs were more practical. "'Actors are harder on things than any other breed of man,'" he told a reporter in 1971, "so I always made dressing rooms 'actor proof,' with lots of sheet metal'" (Duncan).

The theaters growing out of Priteca's designs certainly looked impressive, but that isn't to say that Alexander Pantages's spent a fortune on them. Priteca adopted a Pantages's quote as his own personal mantra: "'Any darn fool can build a million-dollar theater with a million dollars. But it takes a good one to build [a theater] that looks like a million and costs half that amount'" (Duncan, Kreisman [p. 25], and McDermott [p. 11]).

And to this end, Alexander Pantages had a plan: He stressed that Priteca should design shallow stages and small orchestra pits, both of which allowed the venue to hire fewer musicians and stagehands. Alexander Pantages also had his houses designed to practice Jim Crow seating policies -- but only, Priteca insisted, because that's what business demanded. (Priteca maintained that Alexander Pantages was not racist and often settled lawsuits on his seating policies under very generous terms -- very uncharacteristic for a businessman with such a tight-fisted reputation.)

Although he built numerous impressive theaters over his lifetime, Priteca was particularly fond of the Seattle Pantages at 3rd Avenue and University Street, and not simply because the building housed Priteca's own offices from 1915 to 1965. That venue was, in Priteca's estimation, the one that most closely fit the times in which it was built and conformed to Alexander Pantages's view of what the perfect theater should be like.

Priteca oversaw the construction details of each new Pantages house, and frequently worked with same contractors on each project -- A. B. Heinsbergen of Seattle, for example, was the interior decorator for most Pantages houses erected between 1916 and 1931. But no one individual had more input on a house under construction than did Alexander Pantages, who remained closely involved with Priteca on every step. The Priteca Papers at the University of Washington, in fact (consisting mostly of business papers and correspondence from the early to mid-1920s), are littered with memos, notes, and correspondence from the vaudeville showman, who would sometimes engage Priteca on such tiny details as elevator service in his new houses.

However proud Priteca was of his Seattle Pantages, his efforts were topped by the Vancouver Pantages (1917), designed in French Renaissance fashion, and the Tacoma Pantages (1918), the earliest of his theaters to remain standing today (in 2008). But it was his work on the Hollywood Pantages (1930) for which he is most remembered, a radical departure in style in that he employed an Art Deco design. At the opening ceremonies for the Hollywood Pantages, Priteca himself remarked that the theater would "best exemplify America of the moment. Effort centered upon motifs that were modern -- never futuristic -- yet based on time-tested classiccism [sic] of enduring good taste and beauty" (McDermott, p. 7 and Sutermeister, p. 182). Longtime home of the Academy Award ceremonies, it may be the most significant of Priteca's work and holds the distinction of being the last movie house of its kind to open in Hollywood.

Outside the Pantages Circuit

Priteca's work with the Pantages circuit had become his calling card in the industry. "Mr. Priteca has back of him the ideals of old world architecture and possesses the resourcefulness and initiative which enable him to meet the demands of the new world," remarked Clarence Bagley in a 1929 profile. "A scholar in his craft, he his thoroughly acquainted with the various styles and distinctive periods of architecture and shows an unusual power of modifying and combining the qualities composing them ... [Priteca] excels in that branch of the profession and his work has attracted much favorable attention" (Bagley, 443-444). But that isn't to say he was a one-trick pony with the Pantages folks.

When his theatrical designs were in the most demand, during the 1920s, Priteca's offices expanded along the West Coast, perhaps not-so-coincidently in areas where the Pantages vaudeville circuit was also the most active. At one time or another Priteca had branch offices in Oakland, San Francisco, and Los Angeles, though he always called Seattle home -- unlike Alexander Pantages himself, who eventually relocated to California. Priteca was in such in demand as a theater architect, in fact, that he had to remove the phone from his own conference room so he wouldn't be interrupted by calls from one theater chain while meeting with another (Duncan). During his lifetime, Priteca worked not only with the Pantages and Orpheum vaudeville circuits, but also with Warner Bros. and the locallyowned Sterling Theaters.

Priteca's influence was felt all over the West Coast, in Seattle in particular: In addition to theaters spanning from Alaska to California, he personally designed the Admiral Theatre (1942) in West Seattle and the Magnolia Theatre (1948) in Magnolia, the Orpheum (1927) at 5th Avenue and Westlake, the Capitol Theatre (1920) in Yakima, and contributed to the design of Seattle's Paramount Theatre (which opened as the Seattle Theatre in 1928), working alongside the Chicago firm of Rapp & Rapp. Another collaboration took place in 1962, when Priteca worked with James J. Chiarelli to turn the existing Civic Auditorium (1928) into the Seattle Opera House. (The Opera House project wasn't one that Priteca was very enthusiastic about, given the amount of work required and the miniscule $2.3 million dollar budget. When it opened, however, as part of the 1962 Seattle World's Fair, he and Chiarelli won huge raves for their work.)

Even so, Priteca's work went beyond theaters, even from the beginning of his career. He designed Seattle's Crystal Pool (1914) at 2nd Avenue and Lenora, a neoclassical terra cotta building said to be a direct influence when he was hired by Joseph Gottstein (1891-1971) to build the Coliseum Theatre in 1916. His work on Congregation Bikur Cholim Synagogue (1915, later the Langston Hughes Cultural Center) and the Jewish House Educational Center (1916) reflected Priteca's own heritage as an Eastern European Jew. (Priteca, along with another firm, would later work on the design for the Temple de Hirsch Sinai [1960].) He also was involved with the design of Seattle's Public Safety Building (1950) at 3rd Avenue and Cherry Street, a less-than-memorable building that was demolished in 2005.

Easily Priteca's most incredible feat, however, was his design of Longacres Racetrack (1933), built for Joseph Gottstein in a mere 28 days with a construction crew that worked around the clock (Becker). (Gottstein was eager to capitalize on the state of Washington's recent legalization of horse racing following a quarter-century ban.) He picked the right man: Priteca, an avid sports fan, was known to frequent Longacres over the years in order to play the ponies -- and was probably tickled that a special "Priteca Handicap" was run at the track for many years.

Priteca's designs weren't limited to buildings. He once submitted plans for the Locomobile auto, as well as a grille and windshield design for the Paige automobile, forerunner of the Graham-Paige. These may have been a stretch for America's foremost theatrical designer, but were undertaken only partly for the professional experience. Years later Priteca admitted that he took on these challenges primarily because he was interested in the woman who asked him to submit the designs (Duncan). Apparently it didn't work -- Priteca remained a lifelong bachelor.

Honors

Although his designs had been earning raves for decades, it wasn't until 1951 that B. Marcus Priteca was formally recognized by his peers: In that year he was elected a fellow by the American Institute of Architects, the only theater architect in his lifetime to be so honored by the group. Priteca was long held as the "dean" of theatrical architects in America, and the honors continued to come in through the years. Even after his death, in fact, Priteca was extended an honorary membership in the Theatre Historical Society, which lauded him as "the last of the giants" (Sutermeister, p. 184). Later, in 1986, he was recognized by the University of Washington as one of eight original members in a new "architectural hall of fame."

But, despite all his accomplishments, Priteca ("Bennie," to his friends) wasn't a pretentious man and never liked to call attention to himself. A Scottish Rite Mason and member of the Arctic Club, he was -- in his own eyes -- not all that notable. His only claims to fame, he once told a reporter, was that he was one of few Pritecas in the United States, that he smoked in upwards of 20 cigars a day, and that he was one of only a handful of Jews entitled to wear a Scottish kilt (Reddin). He frequently brushed off his professional reputation by calling himself "just an old vaudeville architect," and was always dissatisfied with his building projects. 'I don't think I'm a good architect,'" he told John J. Reddin in 1964. "In fact, I would like to start [every job] all over again" (Reddin).

Last Days

Although the Great Depression brought an end to the era of lavish theaters, Priteca maintained a busy schedule well into the 1960s, when time eventually caught up with the architect -- and many of the structures he helped design. For half a century Priteca's Seattle offices were on the 5th floor of the Pantages Building (eventually, in the 1930s, renamed the Palomar), but in 1965 the building was demolished for the construction of a parking garage. (The site remains a parking garage in 2008. Like overhead wiring, these things don't go easily.)

The demolition of the Palomar marked a bittersweet end for a longstanding Seattle monument, but was one of many Priteca designs to come down during his lifetime. The Crystal Pool had been gutted years before, the Pantages/Palomar demolished in 1965, followed by the Orpheum in 1967. Other once-spectacular venues, such as the Coliseum and Paramount theaters, continued to operate but were hardly the glamorous venues they had once been.

Priteca often claimed that he would retire after the Palomar came down, but in reality he couldn't leave the trade behind, often serving as a consulting architect on projects. ("I've been retiring for 20 years, [but] they won't let me," he frequently exclaimed [Duncan].) Priteca continued to work (and smoke his 20 cigars) almost right up to his death.

Cancer claimed B. Marcus Priteca on October 1, 1971. He was survived by sisters Fannie Green and Esther Priteca, both of Seattle. Memorials were left with Children's Orthopedic Hospital and the American Cancer Society.

Following his passing, many people lauded Priteca's architectural work, but those who knew him intimately mourned instead the passing of a good friend. James Chiarelli, who worked with Priteca on the Seattle Opera House project in 1962, praised not only his professional accomplishments, but also his personal warmth and willingness to teach others. "To [Priteca]," Chiarelli noted, "contentment was a cigar, friends and talk" (Evans).

It was perhaps a sentiment that B. Marcus Priteca himself would have agreed with. "'For some, life has been work,'" he told Don Duncan shortly before his death. "[F]or me, it has been a happy time. It has been nice" (Duncan).