When Ann Marie Burr, 8, vanishes from her Tacoma home in the wee hours of the morning of August 31, 1961, it sparks a massive search for the missing girl and leads police down a maze of dead-end leads. With scant physical evidence, no witnesses, no body, no credible ransom demand, and no known motive, the case everntually goes cold -- until more than 20 years later, when convicted serial killer Ted Bundy allegedly claims in prison interviews that he murdered Ann Burr when he was 14 years old and living in Tacoma. Later, in a handwritten letter to Burr's mother, Bundy denies his involvement, and he is executed in Florida in 1989. Ann Burr's disappearance remains an open case some six decades after she vanished.

Labor Day Weekend 1961

August 30, 1961 was the Wednesday before Labor Day weekend, and the unusually warm weather in the Pacific Northwest had turned muggy. Beverly Burr, 33, spent the day getting her four children ready for the coming school year at Grant Elementary School in Tacoma. Ann, 8, her oldest child, was excited to start the third grade at Grant, the school Beverly had attended as a child. Julie was 14 months younger than Ann and was entering second grade; Greg was 5 years old, and Mary was 3.

The children spent the day playing with friends in their neighborhood. Ann was invited to sleep over at a friend's, but her mother wanted her home as she prepared the children for the beginning of school. Greg and Julie were permitted to spend one last night in a fort they had made in the basement. Julie and Ann usually shared a room; with Julie in the basement, Mary moved into Ann's room for the night. Bev said she was exhausted from the warm weather and hadn't been sleeping well. For a couple of weeks, both Bev and her husband, Don Burr, had imagined they heard noises in the yard at night. At about 11 p.m. on August 30, they locked up the house. Don put Barney, Ann's black cocker spaniel, on the landing between the kitchen and the back door, and Bev put the chain lock on the front door. A living room window was open a couple of inches, so the wires to the TV antenna on the roof could snake through.

That evening, rain drenched the city. Trees blew down, lights went out, and neighborhoods were plunged into darkness. When Bev work up at 5:15 a.m., she checked on Julie and Greg in the basement. They were still asleep. Then she went upstairs. Ann's bed was empty. Bev went downstairs to the main floor and found that the living room window, the one that was always kept cracked, was wide open. The latch on the front door was undone and the door stood open. In her bathrobe, Bev went to several nearby houses, knocking on doors and asking neighbors if they had seen Ann. No one had. She walked around the side of the house. A garden stool had been placed beneath the open living room window. She shook Don awake and they called the police.

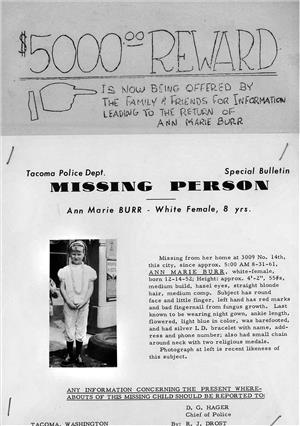

On the front page of the early edition of the Tacoma News-Tribune was a story about the storm. It had rained half an inch and hundreds of people had lost power. There also was a brief item reporting that 8-year-old Ann Marie Burr, daughter of Donald B. Burr and Beverly Burr, of 3009 North 14th Street, Tacoma, was found missing from her bed early that morning and was believed to be a possible victim of amnesia. Police camped out in the basement of the Burr house with a phone set up, hoping to record a ransom demand from a kidnapper. One never came. By the second edition of the newspaper, there was a longer story with a photo of Ann. In the picture, she wears a paper lei she won at a function that summer, and a headband, a blouse with short, puffy sleeves, and pedal pushers. A front-page headline proclaimed: "Girl, 8, Vanishes From Home -- Chief Hager Calls For Wide Hunt" (Tacoma News-Tribune).

The Burr Family

Beverly Ann Leach grew up in Tacoma, the daughter of a grocery store owner. The most memorable event in her childhood came when her closest friend, Haruye Kawanow, was expelled from Tacoma in April 1942, along with hundreds of other Japanese Americans during World War II, and Bev had to say goodbye at the train station. Bev met Don Burr when they were students at the University of Washington in Seattle, and they married in the summer of 1951. Bev, who graduated from Pacific Lutheran University in Tacoma, had been living in one of her father's cabins on Fox Island and teaching school, a job she disliked. She wanted to be a journalist. They spent the first year of their marriage logging in Oregon. Later, after they moved to Tacoma, Don was a civilian employee at Camp Murray, a National Guard base. They were members of St. Patrick's parish in North Tacoma. Bev said her faith would waver and vanish at about the same time Ann did.

North Tacoma was a modest neighborhood, but the houses were tidy. The Burr home, on North 14th Street, just off Alder between Cedar and Junett, was a brick English bungalow built in 1934. Next door was a small orchard near the home of a Mrs. Gustafson. It was a dense landscape of apple trees and thick rows of raspberry bushes. At the end of the street were open ditches 30 feet deep, dug for a city sewer project.

Later, Bev regretted teaching her children that the world was safe. Like many Tacoma families, she didn't know that the city's police records were full of reports of (as the police called them) "sex perverts, exhibitionists, sex oddballs, psychos, crackpots, half-wits, queers, and women with lesbian tendencies" (Burr Missing Person Report). Ann's father didn't trust some of his neighbors, including a woman across the street who had spent time in an insane asylum after she gave birth to a mixed-race baby. There was a man who liked to sunbathe nude in his backyard. The neighborhood children visited him because he gave them candy. Just before Labor Day weekend, neighbors noticed a man in the neighborhood selling cookware, which they found strange because he had no pots or pans. The morning paper was filled with news of the Soviet Union and the U.S. testing nuclear weapons; one man was getting a jump on people's fears, going door to door selling plans for basement bomb shelters.

There was another Donald Burr in Tacoma who had more money than Ann's father, and had a daughter about the same age as Ann. Could his daughter Debra have been the intended kidnap victim? Donald F. Burr was an architect and lived in nearby Lakewood. He had had a messy divorce from Debra's mother, and for awhile detectives wondered if the wrong girl had been taken in a custody dispute.

The Search

As soon as police arrived at the Burr home and interviewed Ann's parents and siblings, Don Burr and his brother, Raleigh, went to search the neighborhood. They examined construction sites at the University of Puget Sound, about two blocks from the Burr home. There were seven campus buildings under construction that week, and there were deep ditches and excavated sites. Near one building site, the men saw a teenager kicking dirt into a ditch with one foot. They thought he had a smirk on his face. Don urged the police to search the campus. He would never forget the face of the teenager standing near an excavated site and watching them search for Ann.

Tacoma had a moniker it had hoped would fade, the "Kidnap Capital of the West." In 1935, three years after the Lindbergh kidnapping, 9-year-old George Weyerhaeuser, son of Washington timber baron John Philip Weyerhaeuser, was grabbed off a Tacoma street in broad daylight. His parents paid a $200,000 ransom, the boy was released unharmed, and an arrest was made within days. Then, two days after Christmas 1936, a man broke into the mansion of Tacoma physician William Mattson. The intruder menaced the four children present with a gun, picked up 10-year-old Charles Mattson and fled. He left a ransom note asking for $28,000. Two weeks later the boy's naked body was found on a snow-covered field 60 miles north, near Everett. The Mattson murder was never solved.

Beverly was 8 years old when Charles Mattson was kidnapped and murdered, and now Beverly's own 8-year-old was missing. Bev and her friends had ridden their bikes past the Mattson house. She would point to it and say, "That's where the boy was taken from." The Mattson case was front-page news, and the Burr case likewise stirred a media storm. Television was relatively new, and the first interview with Beverly was filmed by KOMO-TV, a Seattle station, just hours after her daughter went missing. Said Beverly, haltingly, "Probably the worst has happened to our little girl. I just hope they find her" (KOMO-TV interview).

Within hours there were hundreds of police, National Guardsmen, and Fort Lewis soldiers scouring fields, abandoned buildings, gulches, sewers, garbage cans, and Tacoma's many waterways. It would be the largest search in Tacoma history. It went on for months. Detectives with flashlights crawled under houses and into attics. The Public Works Department combed sewer lines near the Burr house. A three-man crew went underground "using portable lights to probe the pitch-black flumes of the city's sewer network through the North End" ("Full Week Passes ..."). At low tide, volunteer scuba divers went to the end of the line -- the main outfall pipe on Commencement Bay, not far from Tacoma's favorite night spot, The Top of the Ocean -- where the rushing flow of storm drainage and sewage was rapid enough to push a body out of the pipe and into the bay. But it had not.

On September 3, four days after Ann Burr vanished, the city did what Don Burr had suggested just hours after his daughter went missing; it sent men to search the sites being dug at the University of Puget Sound. There's no record of whether the police shared their bad news with Bev and Don, but by the time they went to search excavation sites, they couldn't find any open ditches. "At this time, all ditches are covered and the roads are open," the report in the case file said (Burr Missing Person Report). Traffic was driving over the spot where Don thought the body of his daughter might have been discarded.

The Detectives

At 6:45 a.m. on August 31, veteran Tacoma detectives Tony Zatkovich and Ted Strand arrived at the Burr home. Zatkovich and Strand's white, 1958 four-door Chevy had an Oregon license plate, so they wouldn't look quite so much like cops, but they didn't fool many people. Bev shared with the detectives the story that she would tell hundreds of times, about waking up and looking for Ann. What Beverly didn't say -- to the police, Don, or anyone -- was that she had little hope. "When I first saw that window open, I knew I would never see her again. I knew I would never know what happened," she said years later. "It came to me, just like that. It was a strong feeling. When they were searching, I thought, 'What's the point?' I knew she was gone, and we would never see her again" (Beverly Burr interview with author).

The police tried speaking with little Mary Burr, who was the last to see her sister, but the 3-year-old was too young to articulate if she had seen anything, or else she didn't remember. Bev told police that she and Don had heard Barney, the cocker spaniel, bark during the night, but they assumed he was alarmed by the sound of the wind and rain. The parents told police they thought they had heard someone in their yard a few nights earlier, and three neighbors told police they had seen a peeping tom at their windows, but they couldn't describe the person.

There was scant evidence. A well-meaning relative had dusted the house. Police found a red thread snagged on a brick under the living room window. The bench that the intruder had moved was taken to police headquarters for examination; police thought it had a footprint on it, maybe from a tennis shoe, about the size of a teenager's or a small man's foot. The police were disappointed. There was no sign of a struggle, nothing left behind. Did that mean that Ann knew whoever had entered the house? Had she encountered the man (from the beginning, the kidnapper was assumed to have been a man) in the living room? Was it someone who knew the layout of the house and went directly to Ann's room? Or did she see someone she knew lean through the window and ask her to open the front door, and when she did, she was grabbed by him? Why didn't she make any noise? Or did she?

The police asked for a recent photograph of Ann, and Bev gave them the one of Ann wearing her lei. That evening, and on many evenings for years to come, detectives Zatkovich and Strand sat in the Zatkovich driveway in the white Chevy. They lit cigarette after cigarette and talked about how an 8-year-old girl could vanish.

Investigation and Suspects

Tacoma police questioned thousands of people and gave polygraphs to hundreds of them. It was the biggest manhunt in Tacoma history. The leading suspects included a teenage neighbor boy who flirted with Ann; and Ann's cousin (who grew up to be a convicted child molester). Others would surface over the years.

Complicating the search was the dearth of clues: there were no witnesses, little physical evidence at the crime scene, no vehicle description or license plate, no fingerprints, no credible ransom demand, no motive, no weapon, and no body. There was a footprint and a single red thread. Detectives went to shoe stores in town, trying to track down a boy's or men's tennis shoe that matched the print on the Burr's bench.

The detectives had another suspect three years later. In 1964, an auto parts salesman from Spokane took a 10-year-old girl from Tacoma on a ride around the Pacific Northwest in his Buick convertible. She was dropped off a few days later. The man shot himself as the FBI pounded at his door in Portland, Oregon.

In 1965, a prison inmate in Oklahoma wrote to the Burrs. He claimed that he and a friend, who were picking beans on an Oregon farm, took Ann when they were in Tacoma looking for work. The Burrs gave the letter to Tacoma police, and in 1967 the prisoner was flown to Oregon and a crew dug in an Oregon field. A flood had changed the landscape of the farm in 1964. Nothing was found.

The Bundy Connection

In 1961, no one suspected Ted Bundy, then 14, of the disappearance of Ann Marie Burr, though Bundy had lived in the same Tacoma neighborhood as the Burrs after his mother moved west from Pennsylvania in 1951. Bundy first became known to Tacoma police as a teenage peeping tom and shoplifter. He would grow up to be America's most infamous serial killer.

In 1946, when Eleanor Louise Cowell found herself unmarried and pregnant, she traveled to the Elizabeth Lund Home for Unwed Mothers in Burlington, Vermont, where she gave birth to a boy on November 24, 1946. She then went home alone, leaving the baby, before returning and retrieving him at her father's insistence. As events would show, the child, Ted Cowell (later Bundy), was damaged in childhood. After tests were performed on Bundy in 1986 in preparation for a death-row legal appeal, a psychologist concluded that Bundy lacked "any core experience of care and nurturance or early emotional sustenance" (Lewis interview with author).

In Tacoma, Eleanor Cowell began using her middle name, Louise, married Johnnie Bundy, and raised four other children. By 1974, her firstborn was abducting, raping, and bludgeoning women to death, leaving their bodies in the mountains. Thirty-six murders were attributed to him, but an FBI agent who befriended Bundy said there were at least 50. Bundy implied there were hundreds. His final victim was in Florida, where he was arrested in 1978.

Bundy spent 11 years on Florida's death row. During that time, he did interviews with journalists, a psychiatrist, and researchers. During audio-taped interviews with journalists Stephen Michaud and Hugh Aynesworth in 1980 and 1981, Bundy, speaking in the third person, told them a story about killing a young girl in an orchard. In 1983, Bev and Don Burr read the book based on these interviews, The Only Living Witness. On May 30, 1986, Bev wrote to Bundy: "With all appeals likely to be refused and soon, there is nothing left for you in this world; there can STILL be everything good for you in the next. You have nothing more to lose in this world ... will you write to me regarding Ann Marie?" (Personal letters).

Bundy answered within a few days:

Dear Beverly, Thank you for your letter of May 30. I can certainly understand you doing everything you can to find your daughter. Unfortunately, you have been misled by what can only be called rumors about me. The best thing I can do for you is to correct these rumors, these falsehoods.

First and foremost, I do not know what happened to your daughter Ann Marie. I had nothing to do with her disappearance. You said she disappeared August 31, 1961. At the time I was a normal 14-year-old boy. I did not wander the streets late at night. I did not steal cars. I had absolutely no desire to harm anyone. I was just an average kid. For your sake you really must understand this.

Again and finally, I did not abduct your daughter. I had nothing to do with her disappearance. If there is still something you wish to ask me about this please don't hesitate to write again. God bless you and be with you, peace, ted (Personal letters).

That same year, Bundy again told the story of the murder of a girl in an orchard. Bundy met with Dr. Ronald Holmes, an associate professor of criminal justice at the University of Louisville's School of Justice Administration, who had a two-year grant to study serial killers in the U.S. Bundy told Holmes that he had "stalked, strangled and sexually mauled his first victim, an eight-year-old girl who mysteriously vanished from her Tacoma home 26 years ago" (Holmes interview with author). His admission didn't make news until the next year, when Holmes presented a paper to a conference in Colorado. Bundy told Holmes that he had "stashed the body of Ann Marie Burr in a muddy pit, possibly near the University of Puget Sound" (Holmes interview). Some have discounted the account, but Holmes remained adamant about what Bundy told him.

Bundy told Dr. Dorothy Otnow Lewis, a Yale psychiatrist and researcher who was working with a pro bono attorney to get a new sentence for Budy, that when he was "twelve, fourteen, fifteen ... in the summer ... something happened, something, I'm not sure what it was. ... I would fantasize about coming up to some girl sunbathing in the woods, or something innocuous like that ... I was beginning to get involved in what they would call, developed a preference for what they call, autoerotic sexual activity," he told her. "A portion of my personality was not fully ... it began to emerge ... by the time I realized how powerful it was, I was in big trouble" (Lewis interview).

Bundy was executed on January 24, 1989. The Burrs spent the evening listening to the radio, hoping to hear that he had confessed to more killings, specifically Ann's, prior to his death. He did not.

After

After her daughter disappeared, Beverly Burr made sure the story continued to receive news coverage. There were frequent updates in the newspapers. At the six-month mark. On each year's anniversary. When Bev and Don adopted a baby girl. When they moved from the home on 14th to a different place. In the mid-1990s, Bev received a telephone call from a psychiatrist in Tacoma. He had a patient, he said, who believed she was Ann Marie. Bev baked an apple pie and invited the woman over. "I took one look at her and knew it wasn't her," Bev said years later, "but she was so determined that she was Ann" (Beverly Burr interview). The woman remembered having a canary (as did Ann) and a few other details. Bev and Don visited with the woman five or six times. Finally, Julie encouraged her parents to do a DNA test. "I said, 'Mom, you've got to find out if it's her'" (Julie Burr interview with author). After two years Bev and Don had themselves and the woman tested. The woman was not Ann, but Bev kept photographs of her in an album.

In 1999, 38 years after their daughter vanished, Bev and Don Burr held a memorial mass for Ann. There were numerous articles in the Tacoma and Seattle newspapers revisiting the case and the possible Bundy connection. By then, Bev was glad that she didn't know what had happened to Ann. "I still think it was someone she knew," she concluded. But she was glad she didn't know the details of how Ann died. "You know, he tortured women," she said of Bundy (author interview).

For more than five years, detectives Strand and Zatkovich worked to solve the case. After they retired, they spent another 30 years doing what they did best -- talking it through. It was how they had solved hundreds of other crimes. Zatkovich went back to the police department to get the case file. He was disgusted and saddened to learn that half of it was missing. The two men were still trying to solve the disappearance of Ann Burr when they died, Strand in 1997 and Zatkovich in 2004.

Don Burr died in 2003. Beverly Burr died in September 2008, almost 20 years after Bundy was executed. She was the mother of five, grandmother of seven, and great-grandmother of three. Ann's disappearance remains an open case with the Tacoma Police Department.