On September 15, 1961, after months of planning, Air Force jets scream over South Beach on San Juan Island as thousands of Army infantry troops surge ashore from Navy landing craft in a joint training exercise to "liberate" the local population from "Aggressor" forces already entrenched there according to a detailed scenario. Islanders offer a warm welcome to all the participants and are invited to watch the incursion from bleachers overlooking the landing and first battles. Many have already agreed that their properties can be used for the exercise, which extends across miles of the island over four days before the official "surrender" ceremonies. After the exercise the Army is diligent about repairing or replacing damaged fences, roads, and property; islanders register few complaints. Reviews of the exercise note that much was learned while detailing issues needing attention in future training. The exercise is deemed a success overall, and even into the 2020s longtime residents will reminisce about the military spectacle and their personal encounters with some of the 12,000 participants in this most unusual episode in island history.

Planning Exercise Sea Wall

Events during 1961, including the failed Bay of Pigs invasion in Cuba, the building of the Berlin wall, and the build-up to the Vietnam conflict, emphasized new global areas of concern for the United States and reinforced the importance of military preparedness. As early as April, at a Joint Army/Navy Conference at the Presidio in San Francisco, representatives of the Army 4th Infantry Division and their counterparts in the Navy agreed that a major training exercise was needed to verify readiness and skills. Before the conference closed, a Joint Directive for Exercise Sea Wall was issued and tentative troop participation discussed. That the military should consider having this exercise on quiet, 55-square-mile San Juan Island, located between Canada's Vancouver Island and the Washington state mainland, was not surprising. The U.S. Army, Navy, and Air Force all had major installations around Puget Sound where San Juan Island and the surrounding San Juan archipelago were well-known. In a presentation that April in the Grange Hall in Friday Harbor (the only town on the island and county seat), military officials explained basic aspects of the exercise and sought contracts from residents to use their land for military operations. Assurances were made that damage to roads, fences, or property would be repaired or paid for. Military representatives were subsequently pleased to find islanders "'unusually cooperative' in permitting use of their land for maneuvers with few arrangements" (Keppel, "Sea Wall ...").

Planning started in earnest in early June when staff began to assemble at Fort Lewis south of Tacoma. Lieutenant General John L. Ryan Jr. (1903-1976), newly appointed Commander of the 6th Army, was designated Exercise Director. Colonel Michael Kane Jr. was named Chief of Staff. A general plan, operation plan, control plan, aggressor plan, administrative instructions, and exercise scenario were all developed.

The detailed exercise scenario was created based on specific training objectives for all military units and included opportunities for on-the-spot decision making and problem solving. A comprehensive backstory was developed: The fictional country of Olympia had been taken over by the totalitarian Greenstone regime bringing financial chaos, government power abuse, and censorship. Olympia appealed to the United Nations for assistance, and the U.N. asked the U.S. to accept the task of liberating the country. Well beyond this simple storyline, the scenario included many pages of cultural, political, and socio-economic details about the population of Olympia (only a third were literate; the languages were Olympian and Esperanto; the government included a prime minister and 12 ministries whose heads formed an advisory cabinet) and information on the Greenstone ideology and the representatives already entrenched in Olympia. The leader of their military "Aggressor" unit was said to be General Fritz Prinner, described as "a ruthless and completely dedicated officer, ... author of four books on the history and tactical uses of armor" ("Army Prepares ..."), whose forces were among the best in the world. The person assuming this daunting personality for the exercise was Colonel J. Grant Lemmon (1916-2011), Commander of the Second Battle Group, Army 47th Infantry. This was not the first time that the 47th had provided an "enemy" opponent for U.S. troop training; the "Aggressors" had, in fact, been formed in 1946 at Fort Riley, Kansas, and proven to be skilled and creative adversaries on numerous training exercises through the years.

Exercise Sea Wall was to begin with an amphibious landing on South Beach (called Red Beach in the scenario) on the south side of San Juan Island. Almost immediately some distinctly "island" issues presented planning challenges. The exercise was scheduled for September when the naval ships needed to transport personnel and equipment would be available. However, prime commercial fishing season along the island's south side Salmon Bank took place annually September 1-19, and both the Washington State Fisheries Department and several fishing fleet captains expressed concern that "landing forces can expect to find 210 American purse seiners and 265 gill net boats in the assault zone. Each boat can stretch out about 1,800 feet of net to a depth of 60 fathoms" ("'Armed Forces' Assault ..."). Hastily called meetings between high-level military and state officials resulted in an agreement that exercises would be scheduled for days when the water was not open to commercial fishermen.

And then there were the rabbits – in 1961 a major island nuisance. "San Juan Island is infested with rabbits. Rabbit burrows in excess of two feet in depth will be encountered. Vegetation may conceal these hazards to cross country travel. All cross country travel, vehicle or foot, must be made in consideration of this condition," warned the official rule book (Administrative Instructions ..., 11). One of the greatest concentrations of rabbits and their burrows was along the bluff and prairie directly above the beach where all of the troops and equipment would come ashore and the first battles take place. Twisted ankles, broken legs, and damaged vehicles were definite possibilities. Moreover, rabbit hunting was a popular pastime for islanders and visitors, and clearly rabbit hunters and battle-focused soldiers should not mingle. The sheriff therefore decreed that, for everyone's safety, no rabbit hunting would be allowed in San Juan County from Labor Day through September 22.

A third and perhaps especially anticipated difficulty was that, while much of the Pacific Northwest has dry summer weather, the San Juan Islands are in a particularly strong climatological "rain shadow" and often receive little or no rain from late June to mid-October. In September all vegetation on the island would be tinder dry and the fire danger extremely high. Although in a training exercise no live ammunition would be used, military activities greatly heightened the potential for inadvertent sparks and other ignitions, and fire prevention measures were necessarily given high priority in exercise planning. Ultimately military and state fire crews effectively monitored all activities from a hill that had great views over the action and quickly put out small spot fires as they erupted. These fire prevention and control activities were highlighted as one of the most successful aspects of the operation in after-action reviews.

The Administrative Instructions were lengthy and covered every conceivable aspect of the exercise from what troops should do when encountering livestock on the roads (farming was still a large part of the island economy in 1961) to procedures for processing and treating "prisoners of war" and how simulated nuclear-weapon use was to be undertaken. Islanders especially benefited from military efforts to "keep the American public informed and to merit confidence and support through appreciation and understanding of Army, Navy, and Air Force missions, objectives, and activities" (Administrative Instructions, 65). Information dissemination was manifest partly through 500 observer's handbooks, 3,500 troop information handbooks, 25 press kits, and 2,500 mimeographed handouts for visitors. Accommodations were made for still and film photography; coverage by print, radio, and television news reporters was facilitated.

The first national public announcement of the exercise appeared in The Associated Press reports in July. Island residents had a special opportunity to learn more details at the San Juan County Fair, an annual August event that drew crowds to Friday Harbor from throughout the region. An 8-by-12-foot relief map of the island was on display with areas marked for the planned maneuvers. Exercise personnel answered questions and provided information, and the exhibit was a popular stop for fairgoers. One local resident, Geraldine (Jerri) Rogers (1927-2024), noted that what seemed to be missing from the plan was an equivalent to "Tokyo Rose" of World War II fame, who had broadcast messages to demoralize U.S. troops. She laughingly volunteered to assume that role for the exercise; the military thought it was a splendid idea, even providing her an appropriate Aggressor uniform complete with medals. Throughout the exercise, "San Juan Sue" added her sultry voice to the maneuver's air waves, urging the U.S. troops to surrender with promises of better food, facilities, and treatment if they stopped fighting. Soldiers listening to her enticements probably didn't envision the seductive speaker as a respectable, married mother of three with a twinkle of humor in her green eyes.

Preparing for the Landing

The first Aggressor troops arrived on the island early in September to prepare for the exercise. The South Beach area, soon to be part of the San Juan Island National Historical Park, was then under control of the San Juan Parks Department, a small agency with little equipment for major projects. Local officials were delighted, therefore, when the military decided to bring in a large earth mover and carve a new graded road behind the beach, improve and grade the entrance hill and road, and clear some of the big driftwood logs that littered the beach. Those huge piles of driftwood were expected to be an important, challenging feature of the beach landing and had, in fact, inspired the exercise title Sea Wall.

Air Force units needed encampment for 200 men and staging for helicopters. Organizers met with islander Roy Franklin (1924-2011), who had established the first air service on the island and built the island's airport. Franklin was assured that the military would not interfere with civilian air operations and merely needed space for a camp and fuel for the exercise aircraft. The former was easily managed. The latter was a problem, however, as getting fuel to the island was difficult and labor-intensive, but Franklin accommodatingly ordered 1,980 gallons of special high-octane aircraft fuel, expecting a profit from sale of the supply to the Air Force. The Air Force arrived two days after the fuel's delivery with its own supply. Ultimately Air Force personnel agreed to pay Franklin at cost for the unnecessary fuel purchased. However, they also demanded, despite previous contrary assurances, that civilian air operations cease during the exercise.

The military held an "open house" the weekend before the exercise and islanders were invited to visit the military camps, inspect the tanks, trucks, helicopters, and other military vehicles and equipment, and chat with the officers and troops preparing for the exercise. It was a well-attended event and heralded positive relations between the residents and military. Personal encounters throughout the exercise were friendly; one islander in 2024 remembers her family providing homemade cookies to appreciative soldiers passing long, dull hours on guard duty. The soldiers sometimes unofficially let local children sit in the jeeps and try on the soldiers' helmets.

Meanwhile, troops were massing at Fort Lewis and its marine facility at nearby Solo Point for the exercise. Air Force units from Fort Shawe in South Carolina left for McChord Air Force Base near Fort Lewis to support the landing. (The two later merged to become Joint Base Lewis-McChord.) Amphibious personnel and vehicles left Whidbey Island Naval Air Station for Solo Point and the Port of Tacoma. More than 4,000 sailors and 14 naval vessels from Amphibious Group One and Amphibious Squadron Five (all transport and landing craft; no warships were in the fleet) arrived to transport the Army Eighth Infantry, First Battle Group, and 39th Infantry, Second Battle Group, to the exercise. Finally on Thursday, September 14, the Seattle Post-Intelligencer announced, "At daybreak tomorrow, the 'good guys' will attack [San Juan] island to liberate it from the 'bad guys' who have held it since June" (Angeloff).

Exercise Sea Wall in Action

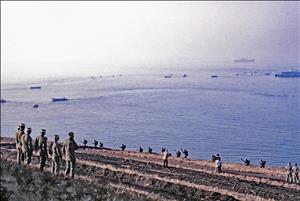

Island residents had been invited to view the landing, and on September 15 approximately 2,000 eager spectators (the total San Juan County population was less than 2,800) arrived carrying binoculars, cushions, and cameras. Schools and most town businesses were closed. The Army provided shuttle buses to bring the enthusiastic adults and children from the fairgrounds in Friday Harbor to the slopes of Mount Finlayson above the landing area where specially built bleachers offered a great view of all the activity.

At 5 a.m., preliminary to the landing scheduled for 7:30 a.m., Navy frogmen emerged from the water to simulate blasting paths through the huge driftwood piles to prepare for moving personnel and equipment on shore. It was a sunny, clear day with little breeze. By 7 a.m. Aggressor forces had set off dozens of smoke pots along the beach to hamper visibility for the landing. Unusually for this type of operation, the landing craft could put troops ashore with dry feet because of the sharp underwater drop off near the beach and the tidal conditions at the time of the landing. A Tacoma News Tribune reporter, whose byline for the day identified him as "staff writer with the Invading Forces" ("4th Division 'Invades' ..." ), described the scene as thousands of troops with heavy vehicles, tanks, armored personnel carriers, jeeps, and weapons carriers navigated 12 narrow channels through the driftwood, while Aggressor forces attacked them from the hillside. F-100 Super Sabre jets simulated dropping bombs and other deterrents while F-101B Voodoo Tactical Reconnaissance Aircraft roared across the sky above the action in support. Landing troops met heavy resistance from Aggressor defenders equipped with small arms and machine guns as well as rockets and howitzer field guns. The invasion had begun.

Fighting along the beach and up the hillside was fierce, as spectators watched enthralled. The islanders were remarkably bipartisan in response to the battle for "their country" and cheered almost equally when skirmishes were won by either side. At least two islanders were most unofficially, but actively, involved in the battle. Wayne Fowler (1927-2023) of nearby Shaw Island owned a World War II fighter aircraft; he and Roy Franklin decided that the U.S. forces needed more challenge and plotted to fly in support of the "enemy" in opposition to the assault forces. It was an undertaking they carried off with glee and skill, infuriating the general in command who fumed that the old fighter had gone "like the hubs of hell right through our coordinated attack ... It was a reckless, irresponsible thing to do" (Franklin, 207). Attempting to identify the culprits after the exercise, he demanded to know whether anyone on the island had an old trainer aircraft. Franklin could, with precision (since the aircraft was not a trainer, and the owner did not live on San Juan Island), honestly answer, "No, Sir."

For the rest of September 15 and the following days, battles ranged up and down San Juan Island, the Aggressors retreating toward False Bay and the interior but continuing to challenge the U.S. forces. They even dropped six guerillas by parachute behind the beaches to harass the U.S. forces from the rear as they moved inland. When U.S. forces seemed to be gaining ground, the Aggressors would counter with surprise attacks, even managing to contaminate (in simulation, of course) the drinking water of the U.S. troops camped near the beachhead. All the action was closely monitored by 37 military "umpires" (57 had been requested but not all were available during the exercise) who determined on the spot what outcomes were achieved, whether the rules of engagement were being strictly followed, and which soldiers became "casualties" or "prisoners of war." As with all aspects of the exercise, appropriate medical procedures were undertaken, with some "injured" soldiers being treated at the hospital tent on shore and others evacuated to ships where they often immediately "recovered" and were reassigned as replacement troops and returned to the island to fight on.

Some soldiers were placed on guard duty on local roads, primarily to assure that residents did not stray into combat areas. After long tedious hours, they were delighted to have visitors stop for conversation. One islander remembers that he and a couple of buddies had been driving around and enjoying the warm evening with a beer or two when they came upon one of the roadblocks, manned by soldiers of about their age. They offered the soldiers some beer, an offer happily accepted, and the soldiers in turn offered to let the islanders try firing their big machine gun (armed only with blanks), an opportunity also happily accepted.

Headquarters for the exercise was located at the popular Mar Vista Resort (which closed in 2013) where a portable post exchange was also established selling, among other products, soda and beer. A real-estate field office was set up in the Friday Harbor Town Hall where islanders could make claims of property damage or other disruption. Few claims or complaints were ever made even when, in early November, long after the exercise, islanders learned that the Army had somewhat belatedly determined that unexploded practice land mines and munitions remained on the island. The residents were warned that any items found should not be touched but reported to the sheriff who would notify personnel at Fort Lewis. The military even planned classes for adults and children on recognizing these items and their potential harm.

In a final push, U.S. forces encircled the remnants of the Aggressor troops near Cady Mountain and fierce fighting supported by combat aircraft eventually severed the Aggressors' communication lines. As the battle raged, the U.S. general ordered a small "nuclear blast" (then considered an acceptable action in certain military situations) to assure the final destruction of Aggressor headquarters and command capabilities. It was reported that "a mushroom cloud boiled above this usually quiet island" (Keppel, "Sea Wall ..."), a simulated nuclear detonation achieved by setting off thickened gasoline in barrels with small explosives creating a dense cloud of smoke. Aggressor forces soon lay down their arms and surrendered (as scheduled). On September 19 a formal "unconditional surrender" ceremony was held, and Col. Lemmon, as Aggressor General Prinner, signed the agreement. Exercise Sea Wall was over.

After-exercise Activities and Review

As most soldiers were leaving the island, some (primarily engineers) were busy restoring damage done to island roads and properties by combat activities and, especially, the heavy military vehicles and equipment. Efforts were made to repair fences, although military engineers were not fence-building experts, and repairs in the middle of fence lines could be difficult; farmers had to redo many of the repairs later. Excess supplies of fencing materials were left on the island; some residents were still using up the stockpiles years later. Ruts and eroded areas on roads were filled, and grading and gravel replacement left island roads in good condition as had been promised. The military, in turn, was pleased that exercise trash could be disposed of at the local island dump rather than needing to be hauled away to the ships. Exercise Director Lt. General Ryan wrote an open letter to the island community that was published in the local paper: "The success [of the exercise] was due in large part to the enthusiastic support of so many of the San Juan Islanders who graciously allowed use of their lands for maneuver purposes. The hospitality received by all of the military will long be remembered" (Ryan). The troops had enjoyed exploring Friday Harbor, visiting local establishments, and meeting residents. After the exercise "as one sergeant put it: 'I've heard lots of guys who want to spend leave time here. They never knew these islands existed'" ("Islanders Have No Gripes ...").

Meanwhile, commanders of the various units and activities during the exercise were writing their reviews, noting outcomes both successful and not so successful. One commander opined that while the objectives of the exercise had been approved during planning, the site and conditions in which the exercise actually took place precluded fulfillment of some of those objectives. Environmental issues were noted: the landing was somewhat artificial, as the seas had been too calm (no roiling waves through which troops had to slog to shore) and the weather and visibility too good (at least for the landing; the second day the island was shrouded in thick fog). The designated landing area was too small for the number of soldiers arriving and consequently they could not disperse effectively. Communications in the field and with headquarters could have been improved. Heliborne and electronic warfare were not part of the exercise (helicopters were only used to transport "casualties" to the ships) and therefore not tested. And other issues were noted as needing further training attention and procedural refinement. A fundamental concern was that the physical fitness of the troops was found to be remarkably low, and "many assault and supporting troops were exhausted by the time they moved inland from the beachhead" (Headquarters Exercise Director ..., 46). Nevertheless, as one commander summarized, "Exercise Sea Wall again demonstrated the ability of the services to function together as one team ... [and] enhanced appreciably the knowledge and competence of all participants" (Commander, Landing Force, 3-1). And it was notable that among the 12,000 exercise personnel, aside from one broken leg and arm sustained on ship before the landing on day one, no serious actual casualties (as opposed to the 149 simulated battle injuries or deaths) occurred, with most injuries limited to simple cuts and abrasions, sprains, toothaches, flu, anxiety reactions, and other minor ills.

Exercise Sea Wall was a major event in the lives of both participants and islanders. In the Puget Sound area, along with days of coverage by Bellingham and Seattle as well as local island newspapers, Seattle CBS television channel 7 featured the entire operation on its September 21 "Assignment – Northwest" program. And soldiers, sailors, and airmen discovered that local newspapers across the country, from the Jackson Independent of Jonesboro, Louisiana, to the Suburbanite Economist of Chicago and from The World of Coos Bay, Oregon, to the Swanton Courier of Swanton, Vermont, had been apprised of the exercise and the participation (by name, rank, and service) of their hometown men, stories they published with pride. On the island, improved (and some new) roads, trampled farmland, collections of unused reconstruction materials, and a few forgotten empty shell casings here and there were physical evidence of the recent activities that had animated the residents' usually quiet lives, but it was the many photos and memories of people met and experiences shared that would be the most lasting reminders of Exercise Sea Wall for San Juan Islanders.