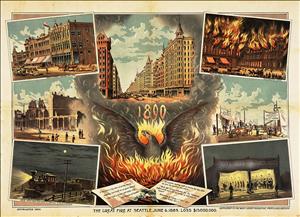

On June 7, 1889, the sun rose over a stunned and devastated Seattle. The day before, a massive fire had ravaged the city's commercial core and its waterfront. Seattle had been booming, and over the previous few years its downtown had been graced by a handful of elegant new buildings made of masonry. But most of the city's commercial structures, large and small, were made of wood, some dating back to pioneer days. The Great Seattle Fire began at about 2:45 p.m. on June 6, and its fury would destroy wood and masonry buildings alike. Within hours banks, stores, hotels, doctors' and lawyers' offices, docks, piers, mills, warehouses, and hundreds of businesses of every kind were leveled. Financial records, medical records, legal records, and entire law libraries went up in smoke; fortunes in goods were incinerated or damaged beyond repair. Remarkably, no lives were lost, and one day later, in an extraordinary public meeting, Seattle's civic leaders and prominent businessmen pledged to rebuild their city in a manner and style fitting to its emerging status as the Northwest's leading metropolis. It was a pledge that was kept, and the city soon was reborn.

Aftermath

On June 6, 1889, the Great Seattle Fire began in a basement of the Pontius Building on the southwest corner of Front Street (today's 1st Avenue) and Madison Street and was soon beyond containment. Sources vary somewhat on the geographical extent of the devastation. One account, published just a few months after the event, was specific, using a ratio of two acres per city block: "The burnt district included forty blocks, or eighty acres, exclusive of the waterfront, which comprises eighteen blocks, making the total acreage of the devastated territory 116 acres" (Austin and Scott, 20).

As the flames began to subside, Mayor Robert Moran (1857-1943) issued a proclamation imposing an 8 p.m. curfew, closing the surviving saloons, and banning the sale of liquor. Despite the mobilization of the National Guard (and contrary to some accounts), martial law was never formally declared -- all those arrested for looting or violating the edicts of the proclamation were handled by the civil courts, whether caught by the local police or by guardsmen. Among the first to be apprehended was a man wearing four new suits.

Tacoma, Seattle's rival for Puget Sound dominance, sent a train north on June 7 carrying a large party of volunteers and several carloads of blankets, tents, and food. The self-styled Tacoma Relief Bureau put up a large tent at the corner of 3rd Avenue and University, where each night they provided cots for about 400 homeless men; each morning they replaced the cots with long wooden tables and passed out free food all day, then put the cots back in place after the last evening meal. They put up a second large tent the next day, which included a separate sleeping space for displaced women and children. All thoughts of regional rivalry were put aside; for days additional supplies arrived from Tacoma on a near-hourly basis, by boat and by rail.

Other festering animosities also subsided in the face of disaster. On June 7, volunteers of the Relief Corps, many from the Woman's Christian Temperance Union, fed more than 6,000 people. On June 8, at the National Guard armory, 10,000 were fed. Among them were several hundred Chinese men, who were invited to return as often as necessary. Just three and a half years earlier, in a shameful episode, mobs of Seattle citizens had forcibly expelled many of the city's Chinese residents. In the wake of the fire, they were regarded as fellow human beings in need and treated accordingly.

Firefighters and equipment came from as far away as Portland and Victoria, and while the worst was well over by the time they arrived, they worked to douse remaining hot spots. Help from outside also came in the form of money. After learning of the fire, Tacomans raised $11,000 within an hour for Seattle's relief, and an additional $10,000 within a few days. San Francisco also sent $20,000, Portland $10,000, Olympia raised $1,000, and Virginia City, Nevada, $4,000. The total contributions eventually exceeded $120,000, nearly $3,500,000 in 2020 dollars.

Although thousands were left homeless, the fire did not reach residential areas north and east of downtown and, miraculously, it claimed no human lives. With no need for funerals or a period of mourning, the city's movers and shakers, who had lost the most but could best bear the loss, turned immediately to the question of how to rebuild. That process began with a remarkable public meeting on the afternoon of June 7, 1889. Before the ashes had fully cooled Seattle went to work on its rebirth.

The Public Speaks

In its first post-fire edition, distributed at 4 a.m. on June 7, the Seattle Post-Intelligencer published a call by Mayor Moran for a public meeting to be held at 11 a.m. that same day "to consider ways and means, and the necessities of the hour" ("The New Seattle"). The meeting's venue was the First Regiment Armory located on Union Street, a large and ornate wooden structure outside the fire zone. Although it had lost its offices and presses in the fire, the P-I was printing a two-page paper at a house at 4th Avenue and Columbia. It carried an extensive account of the citizens' meeting in its June 8 edition under the headline "Full of Hope."

More than 600 attended, mostly businessmen, and what understandably could have been a somber and depressing affair -- a cathartic recitation of losses and blame-placing -- was anything but. There was instead a near-festive mood, as the P-I reported the following day: "Not a single long face was seen. No one not familiar with the facts would have imagined that the assembly, as individuals, was in the midst of a calamity. The air of cheerful earnestness was surprising" ("Full of Hope"). All quotations below are taken from the P-I's account.

Moran gaveled the meeting to order at 11:00 a.m. and led off by posing two fundamental questions: Should Seattle permit the erection of wooden buildings within the fire limits, and should several important streets be widened and straightened. Judge John P. Hoyt (1841-1926), who had served on Washington's territorial supreme court, would serve again after statehood, and managed the territory's largest bank, then spoke. Hoyt told the assembled that "In the work of rebuilding Seattle, the banks may be depended upon to aid with all their power." This elicited three cheer for the city's bankers.

Next up was G. Morris Haller (1852-1889), a lawyer and real estate developer. To loud applause, he stated his opposition to any wooden buildings in the destroyed area. He also proposed, to more cheers, that Front Street be widened by 24 feet, with property owners on either side giving over 12 feet for the cause. Finally, Haller said, "We want to put Front Street right through." More cheers. (Haller would not live to see his city's renaissance; before the year was out, he and two companions drowned while on a duck-hunting excursion near Whidbey Island.)

A Necessary Digression

Haller's comment about putting Front Street (today's 1st Avenue) "right through" was a reference to a problem created in Seattle's earliest days. In 1853 Arthur Denny (1822-1899), Carson Boren (1824-1912), and Dr. David "Doc" Maynard (1808-1873) recorded the town's first plats. The only substantial road was Mill Street (later Yesler Avenue, and today Yesler Way), which ran east and west, dividing the town's oldest, flattest section from what lay to the north.

Maynard, whose plat was south of Mill Street, believed streets should follow cardinal compass points, and he platted his north-south streets accordingly, intersecting Mill Street at a 90 degree angle. Denny and Boren platted their streets to parallel the shore of Elliott Bay, intersecting Mill Street at a more shallow angle. The point where Front Street should have been able to carry "right through" to Commercial Street (today's 1st Avenue S) was barred by the Yesler Block and its magnificent Yesler-Leary Building. The block was lost to the flames, but the old and sometimes cantankerous Henry Yesler (1810-1892) still owned the land it had sat on. He wasn't about to give it up without a fight, but that fight would come a little later.

The Meeting Continues

Jacob Furth (1840-1914), the founder of Puget Sound National Bank, rose next and told the crowd, "The time is not far distant when we will look upon yesterday's fire as an actual benefit to Seattle." He too was strongly opposed to any wooden buildings being allowed in the fire zone. Like Hoyt before him, Furth pledged to great applause, "The banks will do everything in their power to assist the business community."

Elijah P. Ferry (1825-1895), a former Washington territorial governor who in a few months would become the new state's first governor, took a somewhat different tack, arguing that dispossessed businesses should be allowed to build temporary wooden buildings, with the understanding that they would have to be torn down within a year. This proposal was greeted with silence, but Ferry was given "immense applause" when he said, "those who wish to build [with] bricks can get funds of the banks here, and when they run low we can get all the money we want in San Francisco." Further cheers followed his statement that Seattle would accept any aid it was freely offered, but would not go begging.

Almost without exception, speaker after speaker demanded that only brick and stone be used to rebuild the burned parts of the city. There also was near-unanimous agreement that some streets north of Yesler Avenue be joined seamlessly with those to its south, and that several be both widened and raised, the latter to improve drainage of the sewer system, which emptied into Elliott Bay and often backed up during high tides. Territorial Supreme Court Chief Justice Cornelius Holgate Hanford (1849-1926) mounted a chair on the edge of the crowd and brought a motion to appoint a committee of five to plan a replat of the commercial district to achieve these goals. The motion was seconded by "a hundred voices" and "carried with a shout." Near the end of the meeting, a formal motion was raised by Haller to ban any wooden buildings from the fire zone. A "thunder of 'ayes' was heard, followed by cheers when Mayor Moran announced the motion had been carried unanimously."

The final question raised at the meeting demonstrated the city's confidence in its resilience. On May 31, six days before the Great Seattle Fire, a burst dam led to the inundation of Johnstown, Pennsylvania, killing more than 2,200 people. The Seattle Board of Trade had so far raised more than $500 to aid the flood victims. Former Territorial Governor Watson C. Squire (1838-1926) suggested that the money be retained for the benefit of charred Seattle. The proposal was greeted with shouts of "Send it. Send it away. We don't want the money." The money went to Johnstown.

The Recovery Begins

More meetings followed, including one on the evening of June 7 that included the Seattle City Council and in every respect endorsed the sentiments of the earlier gathering. Several issues were definitively resolved. There would be no wooden buildings allowed in the fire zone (the waterfront area being an exception); tents would be allowed as temporary homes for burned-out businesses; the downtown area would be replatted to allow several streets to be widened, straightened, and raised. Throughout the remainder of June and into the summer, the city council passed dozens of ordinances to implement these plans.

Within 48 hours of the fire, some of the displaced businesses had moved to a row of undamaged buildings on the east side of Second Street north of Columbia Street. Across the street, and for blocks south on either side, a sea of well more than 100 tents would soon house myriad other businesses. One contemporary historian described the scene: "Within five days snowy lines of canvas began to cover the blackened blocks, and before a fortnight business was crowding the streets as before. During the remainder of the summer and through the autumn and winter business was thus housed" (Grant, 233).

On June 11 the exhausted national guardsmen were released from duty, but an unruly mob combing through the wreckage seeking valuables brought them back within days. On June 12, Mayor Moran hired 500 men to start clearing debris and salvage bricks from destroyed buildings. The total cleanup would eventually cost the city "scores of thousands of dollars" (Bagley, 427). Rather than remove the rubble, which would have been an arduous and time-consuming exercise, it was decided to build the streets and buildings on top of the charred remains. What could not be salvaged was leveled or used to fill the basements of burned buildings.

One account of the post-fire days, published just a few months later, summed up the prevailing view of the city's future:

"The new Seattle will be a much better city than the old. It will be constructed ... of brick and stone. It will have broad business thoroughfares, unexcelled dockage and wharfage facilities. The old city of pioneer days lies buried beneath 115 acres of ash, but already out of this grave a young Phoenix is rising, glorious in its beauty, and endowed with strength and energy" (Austin and Scott, 35).

Making the Rules

Before new construction could begin, builders had to know where they could build. On June 10, 1889, just four days after the fire, the committee appointed by Mayor Moran (which included Hanford, Haller, and Hoyt) issued its plan for a replat of much of the downtown area. Among the important recommendations that were soon adopted by the city council by ordinance were:

- Front Street and Commercial (today's 1st Avenue S) would be widened to 84 feet by cutting 9 feet off adjacent property on each side; Yesler's Corner would be cut off to allow those two streets to meet;

- 2nd Street, S 2nd Street, and S 3rd Street would be made 90 feet wide by cutting twelve feet off adjacent property on each side;

- The width of Yesler Avenue would be increased from 66 to 90 feet.

A mechanism was established to compensate property owners for the land taken, but they also needed to know what they could build. On July 1, 1889, just three weeks after the fire, the city council passed Ordinance 1147, Seattle's first comprehensive building code. Comprising 44 sections over 61 typescript pages, it led off with the most fundamental requirement: "All buildings hereafter erected within the fire limits of the City of Seattle shall be made and constructed of brick or stone" (Ordinance 1147, Sec. 1). The code also required firewalls between buildings, set standards for foundation walls and for "privies or water closets," set out detailed and lengthy standards for every "theatre, opera house, concert hall, or building to be used for public entertainment" (Ordinance 1147, Sec. 9), and established dozens of other requirements. On July 9 Mayor Moran signed Ordinance No. 1148, which created the city's first Office of Superintendant of Buildings to enforce compliance with the building code.

The Building Begins

The ban on wooden buildings in the fire zone had one immediate and highly beneficial effect -- financial sources from San Francisco and East Coast cities, who had conditioned their investments on just such a provision, stood in line to pour money into Seattle's rebirth. A suggestion to move the city's business district to the flat land south of Yesler Avenue was rejected; most burned-out businesses would rebuild on their pre-fire sites. Although it was known that several of Seattle's commercial streets were going to be raised, that was still in the future. Businessmen and builders were not prepared to wait.

There was one immediate problem. The fire had destroyed the docks and railroad depots necessary to receive the huge shipments of needed building supplies. It was estimated that three-quarters of the bricks from destroyed buildings could be reused, and there were 15 operating brickyards in the area, but getting their output to the burned area remained difficult. Much of the early effort went to repairing the waterfront. One material in abundant supply was lumber. Despite the ban on wooden buildings, this was before the age of steel construction, and wood was still needed to frame the new masonry buildings. Six million board feet were ordered in the first three weeks after the fire. Several small local mills were outside the fire zone, and large mills in Port Gamble, Port Madison, and Port Blakely soon were shipping huge amounts of lumber to the city.

There seems to be no detailed contemporaneous account of the progress of the work other than newspaper reports, but the haste and skill with which it was accomplished was widely commented on. Within a year, more than 400 new buildings were up. A typical summary view is found in Frederick Grant's History of Seattle, Washington, published two years after the fire:

"[J]ust as soon as the embers began to cool, the work of reconstruction was begun, and was continued without interruption until the ruins had been replaced with large and stately buildings and the business district of the city was once more a scene of commercial activity. Indeed, the speed and thoroughness with which Seattle was rebuilt was phenomenal and almost without precedent. Eighteen months after the disaster, all traces of it had been removed. Where wooden building has formerly stood were massive building of brick. Where brick buildings had been were palaces of commerce, the superiors of which few cities possess" (Grant, 235).

The dominant architectural style for the new buildings was Romanesque Revival, with many designed by architect Elmer H. Fisher (1844-1905). Henry Yesler's Pioneer Building on Pioneer Square, designed by Fisher, still stands today as an example of the new construction, and is listed on the National Registry of Historic Places.

Old Henry Balks

Henry Yesler arrived in Elliott Bay in October 1852, already a middle-aged man, and quickly built the region's first steam-operated sawmill. In the words of historian Grant:

"Yesler's mill did not create the town, yet it did more than any one thing to fix the seat of the place ... As the first steam mill, and the first mill of any capacity, it gave a temporary advantage to the town, placing the means of building decent houses and establishing pleasant homes within the reach of the people. The effect of this in fixing the people here was very great" (Grant, 243).

Yesler had the distinction of being known as both a generous benefactor and a litigious rascal. He was not a great businessman, but his large property holdings in what became downtown Seattle eventually made him one of the city's richest men, and he was twice elected mayor. When the post-fire replatting committee recommended that a portion of Yesler's Corner be taken so Front Street and Commercial Street could finally be united, Yesler, nearing 80 years of age, balked. He revoked a million-dollar bequest to the city, complaining that no amount of money would make up for the income he would have reaped from the buildings he intended to build on his corner. He offered the city nine feet of his land, not the 84 feet that was needed, and warned, "Accept this or be involved in litigation with me as long as I live" (Speidel, 247).

On June 26, 1889, the city council met. Seven votes were needed to approve the taking of a portion of Yesler's Corner; one of the eight members of the council was absent, having had a heart attack earlier in the day. When the vote was taken, one councilmember, F. J. Burns, voted against taking the old pioneer's property. It seemed that Yesler had prevailed, and that Front Street and Commercial Avenue would never meet.

The decision was highly unpopular, the press railed against it, and within days the council members realized that all their political futures were in jeopardy. On June 30 they met again and passed Ordinance 1143, entitled "An ordinance to lay off and establish a public square in the City of Seattle." A portion of Yesler's Corner would be condemned for the purpose; Front Street and Commercial Street would be joined, and Pioneer Square created.

But Yesler wasn't through. He sued the city for compensation and was awarded $156,000 for the 13,000 square feet that was taken, or $12 per square foot. (At least one source says Yesler was awarded only $125,000, or about $9.60 per square foot.) All the property owners together who had to surrender land for the street widenings, which totaled approximately 250,000 square feet, received $144,000, less than 60 cents per square foot.

What Lies Beneath

On June 21, 1889, the city council passed a series of ordinances establishing which streets would be raised and by how much. The raising would be accomplished by building thick retaining walls of stone or timber on either side of the streets where they would meet the curb, then filling the space between. New roadways, often of heavy timbers, were placed atop the fill.

Many of the buildings erected soon after the fire ended up having their first and sometimes second stories below the new level of the street, their now-dark entrances and large storefront windows staring out at the retaining walls. At first, ladders or stair led down to those businesses from the edge of the new roadway, but new sidewalks were soon added that further limited light and access. The now-underground levels, no longer easily accessible, were generally abandoned by the businesses above. Some areas became rather dystopian, havens for prostitution, drugs, and other illicit activities. The city finally sealed off access during a typhoid scare in 1907, but parts were reopened in the mid-1960s for commercial underground tours.

Another Silver Lining

In addition to its other benefits, the Great Seattle Fire also brought Seattle its first publicly owned utility. When the fire hit, the city's commercial area was relying on the Spring Hill Water Company, which diverted spring water and pumped Lake Washington water into wooden tanks on First Hill and Beacon Hill. From there it was gravity-fed to the city's downtown in too-small mains made of hollowed logs. The water supply proved essentially and disastrously useless in battling the blaze.

Barely a month after the fire, Seattle voters were asked "whether or not the City of Seattle shall erect and maintain water-works at a cost not to exceed One Million Dollars" (Ordinance No. 1125). The measure was approved by a dramatic margin, 1,875 to 51, and in 1890 the city purchased the Spring Hills Water Company and another private supplier. As the commercial core was rebuilt, new and larger mains were put in place, and eventually the Cedar River was tapped to ensure an adequate supply for the city.

Looking Back

In 1914 writer Welford Beaton looked back on Seattle's renaissance following the Great Seattle Fire and noted that many of those who helped the city recover were among its earliest settlers:

"The frontiersmen had had another challenge; fate lit a torch which called to arms the enterprise and spirit of the people and while the ashes were still warm the task of building the city again began. The men upon whom the city relied, who had fought her battles in the past, again rose to the emergency and proved equal to the task" (Beaton, 10).

And, of course, the women too.