In the heyday of railroad expansion, a bold new line out of Snohomish promised to transform the underserved agricultural towns of the Snohomish and Snoqualmie river valleys. The Snohomish Valley Railroad would bring wealth and opportunity to the rural inlands, served then only by boat or rough dirt road. Boosters boasted of "a sawmill for every mile of track" and courted investors both near and far. But this "bloomingest" opportunity was derailed when the railroad company’s sales agent went rogue, vanishing with half a million dollars of their hard-earned cash and leaving dreams and fortunes shattered.

Dreams of Major Terminus

For decades, Snohomish depended entirely on its river for transportation, with steamboats and canoes ferrying people and goods. Roads were scarce, winding through dense forest and passable only during dry weather. The arrival of railroads changed everything, both easing the burdens of transport and accelerating immigration. And railroad companies did not just build tracks; they sold visions of prosperity and opportunity. The promotional pamphlets and bird’s-eye maps they produced of the communities along their routes –and their decisions on how and where to route the tracks – could make or break burgeoning townsites.

The rail industry’s race to the Pacific Northwest began in the 1870s. Snohomish, still comparable in size and amenities to Seattle and Tacoma, dreamed of becoming a major rail terminus. It hoped to secure the prestige and economic growth that a central rail hub would bring. The first chance at such a line came in 1884, when Emory Ferguson, Isaac Cathcart, Clayton Packard, and other Snohomish civic leaders formed the Snake River, Priest Rapids, and Puget Sound Railroad and Navigation Company. It proposed a pioneering rail route from Tulalip Bay, east over the Cascade Mountains and Columbia River Plateau, to the Idaho-Washington border. Perhaps overeager in its scope, the men hoped to at least sow the seeds of Snohomish’s geographic potential in the minds of larger railroad developers.

Snohomish’s hopes were partly realized when the Seattle, Lake Shore & Eastern Railroad, incorporated in 1885, chose the town as a stop along its line from Seattle to the Canadian border. In July 1888, the first train arrived, though only to the relatively undeveloped south side of the river, as there was yet no bridge to cross it. At 9:30 in the morning on September 19, 1888, after weeks of rapid bridge building, Snohomish was ushered into the modern era: a steam-powered engine pulling seven cars loaded with iron and railroad ties became the first train in town.

By December, the town had service of two trains per day, with the trip to Seattle reduced to a mere two hours. Within a year, the city’s population doubled and the value of its real estate quadrupled. In response to the train’s arrival, news editor George W. Head penned these lyrics set to the tune of a popular song:

"At the sound of the whistle of cars on the bridge

Men, women and children did run.

Each screaming aloud at the top his voice,

The Lake Shore and Eastern is done.

"A town that for years has been counted as dead

To new business and life will soon come,

We all can have wealth to go where we please

Now the Lake Shore and Eastern has come" (An Illustrated History ...).

Railroad magnates rushed to capitalize on the region’s growing market. The Great Northern Railway planned to put a route through the Cascade Mountains. In 1891, it hired engineer John Frank Stevens to survey it and furnished a company-funded home for him in town. Two years later, his work paid off. The Great Northern’s new line passed through Snohomish, connecting it to St. Paul and the East Coast. Though Seattle became the terminus, Snohomish gained access to coast-to-coast rail travel – turning a months-long sea voyage into a journey of mere days. The mountain pass Stevens charted would later bear his name, as would the home at Fourth Street and Avenue C.

Underserved Interior

While major railroads competed for coastal and cross-country freight routes, the rural and suburban interior remained underserved. Snohomish businessmen spotted an opportunity: a rail line through some of the state’s most productive and fertile farmlands. They envisioned a route along the Snohomish and Snoqualmie river valleys, a "thickly settled section which needs rapid transit to make it the richest portion of [the] county" ("Snohomish To Have New Trolley Line"). They would employ the latest engine technology – electricity – which ran faster, quieter, and emitted no smoke like the coal and steam ones did. Most importantly, the line would be under local control, a "people’s road," where "every farmer along the route, every citizen of the mountain hamlets and in the rich farming region, was to be invited to take stock" ("Snohomish is Aroused").

The first public meeting to discuss the vision was held on July 31, 1903. At the time, there were several rail and trolley lines under consideration, all seeking exclusive rights to a city franchise, but these were outside enterprises seen as "suckers," rather than "feeders" that would bring opportunity to Snohomish ("Snohomish is Aroused"). This plan was different, taking shape as a community-controlled passenger trolley line, under contract directly with the city of Snohomish, which would receive an annual 2 percent investment of the company’s gross earnings. William Snyder, cashier of the First National Bank, was selected to lead it, and he hired civil engineer E. Lloyd Colburn to survey the proposed route. Colburn found the farmers southeast of the city "enthusiastically favorable to the creation of the proposed line" (An Illustrated History ...). In April 1904, the project was officially incorporated as the Snohomish-Cherry Valley Trolley Company.

A few months earlier, in December 1903, an electric trolley line had opened west of town, connecting Snohomish with Everett. It was a triumphant success within its first few months of operation. The Everett Daily Herald reported that "parties of tourists dropping into Snohomish from train and trolley cars have become quite common, and so favorably have most of the visitors been impressed, that people here are anticipating an influx of new residents and the beginning of a new industrial era" ("Looking at the Town"). The promise and benefits of rail seemed guaranteed.

The following year, the Snohomish-Cherry Valley Company reorganized as the Snohomish Valley Railroad (SVR) and established an office in the Marks Building. The restructuring aimed to develop a more robust company, capable of managing a larger rail system. The SVR’s scope expanded – now meant to serve both industry and passenger needs – and supporters hoped this would attract deep-pocketed investors. George M. Cochran, the owner of the Snohomish Hardware Company and one of the leading merchants of the city, became the company’s new president. Alongside him as vice-president was Colburn, the project’s original surveyor; Oscar E. Crossman, a dry goods store owner, as treasurer; John P. Tinley, an attorney, serving as secretary; and Charles A. Barron, a former employee of the Great Northern, as general agent.

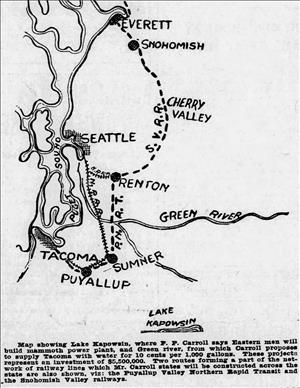

The SVR mapped out an ambitious 55-mile route. It would run east from Snohomish to Monroe, then south through Cherry Valley, Tolt, Issaquah, and Renton, where it would then connect to an existing line out of Seattle. An additional spur would head southwest from Snohomish, crossing the river and following the base of the hill toward Lowell. The prospectus delivered to investors noted numerous sawmills, dairies, and fruit businesses along the path that were eager for rail service, ensuring a steady flow of shipments. "The road will be immensely useful in building up the country traversed by it," declared project promoters in the Herald. "[It] will furnish transportation for products of farm, mill and forest as well as general merchandise, and will offer frequent and speedy passenger service" ("Contract For New Trolley Line Let"). Reported the Herald on March 13, 1906:

"Everett is the western terminal of the Snohomish Valley railroad. Its course from Everett is in an easterly direction along the south side of the Snohomish Valley to Monroe, there crossing the Skykomish River, thence along the north side of the Snoqualmie Valley to Cherry Valley, thence continuing along the same valley to Novelty, thence to Tolt, crossing the Snoqualmie River between Tolt and Fall City, passing within one and one-half miles of Fall City, thence via Patterson Creek Valley to Issaquah, thence via Issaquah Creek to May Creek Valley, thence via May Creek Valley to the town of Kennydale (Garden of Eden), thence continuing via May Creek Valley and the shore of Lake Washington to Renton, which is about 14 miles from Seattle and served by two interurban lines with hourly service" ("Contract For New Trolley Line Let").

With enthusiasm and regional support behind the project, the SVR faced a critical challenge: securing rights of way from landowners along their proposed route. This was a difficult and tedious process, requiring the railroad company to negotiate with and pay individual property owners for permission to lay tracks across their acreage. Beyond the financial cost of purchasing all 55 miles of rights of way, the effort demanded extensive relationship-building, legal work, and grading and stump clearing before the first mile of track could be laid. To fund this phase, the organizers hoped to raise $750,000 through the sale of gold bonds. Their first offering launched in the fall of 1905. These bonds, ensuring buyers 5 percent annual interest, were marketed with confidence that the railroad would generate strong profits. Secretary Tinley told investors, "We expect to begin throwing dirt on the right of way within ten days ... We have succeeded in getting some of the best men in the city to take hold of the matter, and with such men interested there can be no doubt of our putting things in such shape that the road can be bonded for capital to build it. Do we have confidence in the road being built, and paying after it is completed? We surely do" ("Valley Railroad Files Articles").

Seeking Investors

Investors were told they could redeem their bond tickets for regular payments, plus interest, beginning July 1906 and see full repayment in 30 years. A few sales were made locally, but the project’s ambitions and financial demands stirred President Cochran to seek capital from financiers on the East Coast. He took multiple trips to New York but returned with mixed results. Railroad speculation was a crowded market, and the SVR’s reliance on the cooperation of so many individual property owners in a far-flung corner of the remote Northwest made the venture seem risky and speculative.

Support back at home was also waning. Sentiments had shifted since the original proposal for a local trolley line in 1904. The project had grown more ambitious – its latest plans numbered 71 total miles with added spur lines – and doubts were mounting. The board of trustees always seemed busy and the project seemed to be moving forward, but continual rebranding, restructuring, and rerouting in a quest to find more capital had done little to instill confidence that this would truly be a "locals-first" rail line. Frustrated by changes, uncertainties, and delays, locals began to refer to the railroad as the "hot-air line."

Another pivotal task was renewing and securing the company’s franchise with the city of Snohomish and, crucially, whether the agreement should last 35 or 50 years. Now with a few years of construction delays, their original contract had expired. The city had also grown skeptical and preferred the shorter term, but Secretary Tinley insisted that SVR needed a long-term commitment to be viable, and that outside investors would balk at a 35-year franchise. Yet "even this statement," wrote the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, "failed to arouse any great interest and his proposition to pay the expenses of a special election submitting the matter to the people was waived aside and the matter disposed of for two weeks by referring it to the ordinance committee" ("Trolley Road After ..."). Meanwhile, citizens and council members also grappled with the SVR’s request for expansion of railroad property and rights of way, which would impact several key streets. Plans required laying the track parallel to First Street, disrupting infrastructure already built along the river's edge, and tunneling northward through a stream gulch below the streets of Union and Cedar.

On April 16, 1906, the issue went to the voters, who were asked two ballot questions: whether to approve a new city franchise for the SVR, and if so, for what length of time. Over 300 votes were cast, and while the majority of voters did support a 50-year franchise, when asked whether the SVR should be allowed to build at all, the vast majority voted no. News reporters saw "little likelihood of the franchise being granted" unless "the council is assured beyond peradventure that the concern is financially able to carry out its plans to the letter" (Minutes ...). The mayor appointed a committee to consider the implications of not granting the franchise and to rewrite the ordinance concerning the SVR.

The SVR’s agent Barron, known for having a loose tongue and hot temper, threatened to run the track elsewhere if SVR did not get the 50-year franchise. He warned he could easily spend "a few thousand dollars" of investment money building a new business block northeast of town, which would not require city approval for its route and potentially siphon business away. He made a similar threat to the Everett City Council a week later, threatening to bypass that city. After months of heated debate, all came to a head at a special Snohomish City Council meeting held at the Eagles' Hall: "A crisis comes in the lives of every one, so does a crisis come to every city," read that week’s editorial in the Herald, "And the mass meeting at Eagles’ hall tonight is a crisis in the history of Snohomish, compared with which the removal of the county court house fades into insignificance" ("Meeting Will Be Important"). Perhaps under duress, and desiring to be done with the whole thing, both Snohomish and Everett finally granted the 50-year franchise, providing the SVR project with a critical lifeline.

Meeker's Duplicity

Yet financial hurdles continued to plague the project. Still needing to secure investors, Cochran increased the amount of capital stock to $2,500,000, more than triple the company’s initial ask. He enlisted Charles M. Meeker to help it. A seasoned railroad speculator who had lived in Snohomish 20 years prior and witnessed the dawn of the railroad age, Meeker was now representing the Bank for Foreign Trade in London and proposed travelling to Europe to target the major money markets of London, Paris, Antwerp, and Berlin. European investors were keen on high-risk American ventures that promised lucrative returns, and Meeker assured the SVR he would find eager buyers. In February 1908, Meeker packed a suitcase full of $500,000 in SVR bonds, now totalling a fifth of the company’s value, and boarded a ship out of Seattle.

Confident they would soon meet their funding goals and secure the last remaining rights of way, the SVR pressed forward and signed a contract for building the "long-looked-for trolley line" ("Contract for Trolley Line") with the Continental Engineering & Construction Company of New York. Known for their successful regional rail lines, the company planned to complete the line within eight months. The SVR’s southern terminal in Renton would connect with the Continental Company’s Puget Sound-Chelan-Spokane Railway and the Puyallup Valley Northern Rapid Transit Company, solidifying SVR’s place in the region’s growing network. Continental made a subcontract for immediate clearing and grading with a local Snohomish construction firm, which "pleased the people here and added not a little to the feeling that the tide of prosperity was rising" ("Snohomish Pleased").

Snohomish residents and SVR investors celebrated the progress. SVR even expanded its offices, to a new two-story building built by Vice-President Colburn, and hired a bookkeeper, pledging that work would commence as soon as possible. But the optimism was short-lived. In August, their new office at the corner of Cedar and First Street burned in a fire. The entirety of the company’s records were incinerated, including "field notes covering fully four years’ work" and maps, "which will cause much delay in financing the road" ("Snohomish Suffers ..."). Barron, just back from New York, seemed unfazed at the setback. He assured the local public that there was an "astonishing number of people looking towards Puget Sound. Financiers on Wall Street all have their eyes on this region" ("Big Things Only"). Money to recover and renew work on the project would be no issue, he said, as the people SVR was courting "think in millions, talk in millions and handle millions. Mr. Meeker told me that a twenty million proposition takes no more time to investigate than a little scheme; and they have so much money to invest yearly they pass up the little schemes for actual lack of time" ("Big Things Only"). The more money SVR requested, the more appealing it became to investors.

With such published reassurances, other regional rail lines begin to spring up, hoping to connect with the route of the SVR. Work to clear and grade did commence the following spring. But in July 1909, SVR officers made a startling announcement: their agent, Charles Meeker, had deceived them. His banking credentials were forged. And though he had successfully sold nearly all of SVR’s bonds, he had kept the half million in proceeds for himself.

Desperate to contain the fallout, SVR officers urgently sent letters and telegrams to financial agents in the East, as well as in London and Paris, warning them of Meeker’s fraud. Cochran reported the scheme to Scotland Yard, triggering an international manhunt. Unfortunately for Snohomish, both the financial and reputational damage was irreparable. The SVR drained its remaining funds trying to recover the stolen bonds and compensate defrauded investors. They had no choice but to cancel the remaining gold bonds, recall their agents, and cease operations. Years later, after the dust had settled, local papers lamented that the fraud "nipped in the bud one of the bloomingest little promotion blossoms ever reared in Snohomish" ("Meeker is in Trouble ...").

Word of the company’s collapse was slow to spread overseas. Meeker exploited the confusion, continuing to sell fraudulent bonds to unsuspecting foreign investors. Two years later, he was finally arrested in New York and extradited to Texas, where he faced separate charges of banking and check fraud across multiple southern states.

Dying "a Natural Death"

With the SVR defunct, a rival group of Everett businessmen, who had battled SVR in court over rights of way near Snoqualmie, formed the Cherry Valley Traction Company. They surveyed a route nearly identical to the one the SVR had planned. Now recognizing the region’s potential, the Great Northern ended up purchasing the line and developing it. While the original organizers were surprised – and perhaps sore at another railroad’s success and lucrative buyout all built upon their efforts – they accepted the outcome with grace. Publicly, they stated their ultimate goal had been to see the railway built, regardless of who carried it out.

The ghosts of the SVR’s ill-fated tracks lingered. Through the 1920s and 1930s, letters postmarked from Europe flooded Snohomish’s post office, with inquiries from investors curious when they might see a return of their investments. Locals wrote back to deliver the hard truth: They had been swindled. The Snohomish Valley Railroad was nothing more than a paper trail. Today, lithographed sheets of $25 gold bond certificates occasionally surface in antique stores across both America and Europe.

"Some time ago, W. J. Marvin, real estate man, 718 Second Avenue, acquired 532 shares of stock in the Snohomish Valley Railway company, a corporation organized under the laws of Washington in September 1904. Today, in a communication to county assessor William Whitfield, he inquires as to the value of his stock. Perusing the records of ancient vintage, water-soaked records that had rescued from the court house fire of August 3, 1909, Whitfield this morning learned the history of the railway company, which is now defunct. It was incorporated by Snohomish men with a capital stock placed at $750,000, divided into shares at the par value of $10 each. The principal place of business of the corporation was Snohomish. However, this company, to the best knowledge of Whitfield, never built a line, and the company died a natural death" ("Asks About Snohomish ...").

Despite the disappointment of the railroad, Snohomish flourished as a well-connected community. By 1911, the town was served by major rail lines, including the Great Northern, Northern Pacific, and Milwaukee Road, as well as the local interurban trolley to Everett. Tracks and trains came and went for decades until the last depot closed in the 1970s, though daily rail traffic still rumbles along the Burlington Northern line just south of the river. In the end, Snohomish became a rail hub as it always wanted to be.