Thanks to Seattle's damp and soggy weather, coffee has always been a cherished commodity. The city's first commercial roasting operations began producing fresh-roasted coffee more than 100 years ago, and the coffeehouse scene of the 1960s introduced espresso drinks to local aficionados who would then transform Seattle coffee culture into various multimillion-dollar businesses. From primitive coffee kettles to state-of-the-art espresso machines, the science of roasting and the art of brewing the perfect cup have evolved thanks to local innovators and a tech-savvy environment where coffee has become an integral part of the city's metropolitan identity.

Early Coffee Roasting

Coffee tends to be roasted close to where it will be consumed as green coffee is more stable than roasted beans. In Seattle, prior to the emergence of commercial coffee roasters, home roasting was the norm for most local residents. This changed in the 1880s when commercially-roasted coffee was popularized following the patenting of various roasting machines. At first, roasted coffee was shipped to the region from other parts of the country, with the majority coming from San Francisco. However, coffee roasted elsewhere often grew dry and stale during the shipping stage, which prompted Seattle's first roasting operations to open. In most cases, it was mercantile and grocery stores that began roasting and selling their own coffee to local consumers, which led directly to some of the region's earliest brands.

The first known Seattle coffee roasting business was opened by Dan Davies (ca. 1862-1949) when he started roasting and selling coffee as "D. Davies & Co." in 1887. Others soon followed, including Schwabacher Brothers & Company -- a mercantile-style store that had opened in Seattle in 1869 and sold everything from dry goods to clothing. Sometime in the late 1890s the Schwabacher business started roasting and selling its own line of coffee called Gold Shield, which was carried by local grocery stores. Gold Shield became immensely popular and is widely regarded as the city's first true coffee brand since Schwabacher was the first business to sell large batches of its own roasted coffee for local distribution.

In 1908, Edward (1872-1956) and William (1874-1939) Manning -- sibling coffee merchants from Boston -- moved to Seattle and opened Manning's Coffee in the newly opened Pike Place Market. Occupying the site where Lowell's Restaurant now sits, the company roasted, blended, and sold its own coffee using a giant roaster that sat in the middle of the store. Pricing coffee at only 2 cents per cup, it quickly became a popular business and soon expanded the menu to include food and baked goods. This success allowed the brothers to expand and by 1915 other Manning's locations began opening -- first in Seattle and then in Everett and Spokane. In the 1920s, the company expanded further, to locations in Oregon and California. Initially, the original Seattle location remained the flagship store, but as Manning's continued its expansion into California, its administrative headquarters eventually moved to San Francisco and the central coffee-roasting plant soon followed. By the 1930s, the business had grown to more than 60 locations up and down the West Coast, including 10 in Seattle.

Starting in the 1950s, Manning's began to shift to the hospital food-service industry and phase out of the coffee business. The company's exit from the coffee world was further dramatized in 1957 when the original Pike Place Market location was sold to local restaurateur Reid Lowell, who renamed it Lowell's. Even after most of its coffee locations were closed, Manning's Coffee was still sold in local grocery stores until sometime in the 1970s. While no longer in operation, Manning's holds the distinction of opening the first chain of local coffee shops that served its own brand of fresh-roasted coffee.

Another early coffee business was a Seattle-based brand called Reliance that was manufactured and distributed by Natural Grocery Company, a wholesale food corporation. Natural Grocery launched Reliance Pure Foods in 1902, with the Reliance coffee brand being introduced in 1905 and remaining a staple at area grocery stores for the next several decades. In 1957, Reliance was purchased by the Crescent Manufacturing Company, a Seattle-based spice and seasoning business, which discontinued the once-popular coffee brand in the early 1970s.

The First Coffeehouses

During the 1940s and 1950s, coffee shops such as Manning's became locally popular. Walter Clark (1897-1990), a Seattle restaurateur who once worked as a roaster for Manning's, operated some counter-and-booth style coffee shops around town, and the Benjamin Franklin Hotel Coffee Shop served as a popular gathering spot for business travelers. Things took a decidedly more bohemian turn in the late 1950s when the city's first coffeehouses began appearing thanks to their popularity in the burgeoning beatnik scene. Coffeehouses became gathering places where people conversed and exchanged ideas. Most of them provided art and live music (usually folk or jazz) and were immediately seen as an interesting alternative to the staid and often sterile environments of the typical coffee shops of that era. What really set coffeehouses apart, though, was their artisanal approach to coffee itself with the introduction of espresso. Instead of a cup of traditionally brewed coffee, as was standard at the time, coffeehouses began offering a variety of espresso drinks such as macchiatos, cappuccinos, and lattes. Importantly, these early coffeehouses planted the seeds for new local coffee business to take hold, which in turn would lead to Seattle's eventual rise as one of the coffee capitals of the world.

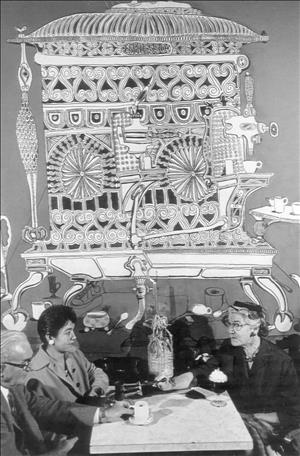

Seattle's first coffeehouse was Cafe Encore, which opened in 1958 in the University District. Several months later, in 1959, Ben Laigo opened The Door in downtown Seattle. The Door was the first such establishment to make coffee drinks using a traditional espresso machine, which had to be specially installed by a plumber. As was reflected in its name, The Door was also the first coffee place to truly embrace its bohemian roots. Laigo had carefully studied the beatnik-populated coffeehouses in San Francisco and went to great lengths to recreate that same atmosphere at The Door. As he explained, "I took one look at coffee houses thriving up and down the coast and decided Seattle could use one" (Laigo interview). Soon, other coffeehouses also began appearing, including The Place Next Door, Kismet, The Matador, Pamir House, and The Last Exit.

By the early 1960s, coffeehouses had significantly grown in popularity. A 1959 advertisement for a more traditional established coffee shop mockingly acknowledged that trend: "Coffee espresso houses are fast becoming 'the' spots in town. Here one finds the pseudo-intellectuals, the ... Beatniks, people just a little different" ("Ruth's Coffee Espresso"). The 1962 Seattle World's Fair boasted its own coffeehouse called the Sleeping Buddha, which featured espresso-style coffee, folk singers, and an abstract art display. After the fair ended, the owners of the Sleeping Buddha took all its furnishings and equipment and used them to open a new coffeehouse called Eigerwand. When the hippie movement later took hold, local coffeehouses often served as hangouts. At the time, the majority of coffeehouses were located in the University District, helping establish that neighborhood as the local epicenter for the 1960s counterculture.

It was also during the 1960s that the Seattle Coffee House Association formed. This was in response to a city ordinance that classified coffeehouses as cabarets since they provided live music. As a result, local coffeehouses were forced to follow strict cabaret laws, including expensive licensing fees and not allowing minors inside. The association, which included such places as Cafe Encore, The Place Next Door, Pamir, The Door, Yesler 92, and several others, used its power as a group to get the minimum age limit removed and have the cost of the licensing fees lowered. It was significant in that it brought local coffee businesses together for the first time and helped establish their prominence in the local region.

Coffee Capitalism

Seattle's robust coffeehouse scene led to a strong affinity for espresso-based drinks. From this, a small movement of local coffee zealots emerged who would take their caffeine-fueled inspiration and use a more unconventional style of entrepreneurship to create various industry-changing businesses. These early coffee ventures often had symbiotic relationships with one another, helping advance the subsequent innovations that would soon be taking place within the regional coffeescape.

The first significant new venture to take hold started in 1970, when three men -- Jerry Baldwin (b. 1942), Gordon Bowker (b. 1942), and Zev Siegl (b. 1942) -- developed plans to open a downtown coffee store. They had managed to establish an important business connection with Alfred Peet (1920-2007), who ran a successful gourmet coffee company in Berkeley, California. To help prepare the three men for the opening of their store, Peet taught them the art of coffee roasting and instructed them on the business side of things. Soon after receiving this coffee education, the three men opened the first Starbucks near Pike Place Market on March 30, 1971. During its first several years in business, the store only sold Peet's roasted coffee beans and did not sell brewed coffee or other drinks. With Peet's encouragement, though, the fledgling company opened its own roasting plant near Fishermen's Terminal on Seattle's Salmon Bay, giving birth to Starbucks' own unique brand of dark-roasted coffee. In 1976, the Starbucks store moved a short distance into the Pike Place Market itself. Despite the move, this second location -- near the site of Seattle's first coffee shop chain, Manning's -- is now commonly referred to as the "'original' Starbucks" (Farr).

Another important development took place in 1974 when Kent Bakke (b. 1953) assumed co-ownership of a Pioneer Square cafe that came with a broken-down espresso machine. Trying to repair it himself, Bakke began tinkering around and subsequently developed a fascination with such machines. As a result, he soon traveled to Italy to learn more about the industry and visited the La Marzocco factory in Florence -- a family-owned business noted for top-quality espresso machines. La Marzocco machines were known for saturating the coffee grounds with more water before brewing, which led to better flavor, and were therefore considered the world's best. Bakke struck a deal with La Marzocco in 1978, allowing him to become the first U.S. distributor of its machines. The following year he opened his own Seattle-based sales and service company called Visions Espresso, which sold espresso machines to local restaurants and coffee establishments.

During this same period, the beginning of another important coffee venture was also underway. It began in 1970, when Jim Stewart added fresh coffee to the menu of his Whidbey Island ice cream store, the Wet Whisker. Stewart initially purchased wholesale coffee from Boyd's in Portland, Oregon, but in 1971 he began roasting his own coffee. In contrast to the notoriously darker roasts that would soon be associated with the Starbucks brand, Stewart always kept his roasts on the lighter side of the spectrum. In 1977, Stewart began traveling to Indonesia and South and Central America to buy his coffee beans directly from indigenous farmers, helping to pioneer the practice of direct-trade and ethically sourced coffee. This variety of high-quality coffee from different parts of the world helped grow his business, and in 1981 the Wet Whisker was officially renamed Stewart Brothers Coffee, with the company's roasting operation later moved to a historic building on Vashon Island.

The Espresso Revolution

In 1982, Starbucks began selling brewed coffee and later that year Howard Schultz (b. 1953) was hired as director of retail operations and marketing. In 1984, Schultz purchased one of Kent Bakke's espresso machines. At the time, Starbucks was still primarily a coffee-roasting business and Schultz wanted to switch the focus to opening a series of espresso cafes similar to the city's coffeehouses. Armed with the new La Marzocco machine, Starbucks opened its first espresso bar in 1984, paving the way for the future course of the company. In 1987, Schultz purchased Starbucks from its founders, at which point he became the company's CEO.

Further innovations continued in 1988 when former Boeing engineer David Schomer (b. 1956) opened Espresso Vivace. It began as a small, downtown espresso cart, later moving to Broadway Avenue where it would become a Capitol Hill icon. The company also opened a coffee roasteria nearby on Broadway. Using his engineering background, Schomer took an almost mathematical approach to vastly improve the quality of espresso shots, as well as perfect such factors as milk foam and texture. As he tells it, "After acquiring a scientific training in metrology I just had an intuition that I could do something real special with the espresso method" (Schomer interview). He then taught these methods to others, helping to establish a local network of professionally trained baristas, and wrote the influential book Espresso Coffee: Professional Techniques: How to Identify and Control Each Factor to Perfect Espresso Coffee in a Commercial Espresso Program.

In 1991, Stewart Brothers Coffee entered a televised tasting competition, held by the McCormick and Schmick's restaurant, to see who had the best cup of coffee in Seattle. It won the high-profile contest, earning the title of "Seattle's Best Coffee." At the same time, it was learned that another Stewart Brothers Coffee existed in Chicago, forcing a name change. For the Stewarts, the decision was easy -- they simply adopted their prestigious new title and became Seattle's Best Coffee. "The name kind of ... well, just fell into our laps," recalled Jim Stewart ("On the Shoulders ...") The following year, Tully's Coffee was established by Tom "Tully" O'Keefe (b. 1954), who sought to rival the expansion of Starbucks with an alternative business model that offered a milder roast, and used overstuffed chairs and fireplaces to create a comfortable and soothing environment. The first Tully's opened in the town of Kent in 1992.

Meanwhile, Starbucks continued to open an increasing number of cafes throughout the country. During this massive expansion, the company used La Marzocco espresso machines as they were so reliable and well-crafted. For Kent Bakke, this meant a significant ramp-up in production, but importing that number of machines from Italy proved to be problematic as they were so heavy and bulky. In order to keep up with demand, Bakke purchased a majority stake in the company in 1994, which allowed him to open a local La Marzocco factory in Seattle's Ballard neighborhood. At its peak, the Ballard factory produced some 140 machines a month, with about half of them going to Starbucks and the other half going to the opening of various new coffeehouses that were sprouting up throughout the region.

The following year, in 1995, David Schomer introduced latte art to Seattle and created a video course titled "Caffe Latte Art," which quickly helped to spread the unique art form to all areas of the world outside of Italy, where it had originated. That same year saw the opening of new local independent roasters, including Caffe Vita Coffee Roasting Company, which were significant in helping to further Jim Stewart's pioneering practice of sourcing coffee beans directly from indigenous farmers and developing longterm relationships with them in order to use fair labor and sustainable practices. In turn, these beans would produce a variety of top-quality coffee that became a hit with local consumers. This use of ethically sourced and artisanal coffee helped define local roasters and coffee shops throughout the dot-com boom of the 1990s and beyond.

Seattle Coffee in the Twenty-First Century

To date, the most significant changes to take place in the Seattle coffee industry during the new century have been technical innovations. The previous decades that were dedicated to the art and science of brewing the perfect cup of coffee culminated, in a very tech-savvy city, in some remarkable advances in coffee-related technology. These technical advances were part of a larger chain of events that was inadvertently triggered in 2004 when Starbucks decided to simplify its barista training by switching to automatic push-button espresso machines. This meant that its cafes would no longer be using La Marzocco machines, and the sudden loss of Starbucks business forced the closure of the La Marzocco factory in Ballard and layoff of all its employees. While the plant's closure would come to symbolize the end of a coffee-brewing era, it would also help to usher in a new chapter marked by high-tech brewing equipment.

Among the longtime La Marzocco employees who lost their jobs was Mark Barnett, who had worked in the company's research-and-development department. After the factory closed, the newly unemployed Barnett set out to build a superior espresso machine with better pressure and temperature control, resulting in the founding the Synesso company and the invention of the Cyncra espresso machine. One of his first customers was Espresso Vivace's David Schomer, and by 2023 there were about 1,000 Cyncra machines in use.

In 2004, Zander Nosler co-founded the Coffee Equipment Company in Ballard and invented a high-end espresso machine called the Clover that brews a single cup of coffee at a time using custom controls that help bring out the flavor profiles of different roasts. Starbucks acquired the company in 2008, giving it exclusive rights to the Clover brand of machines. In 2007, two former La Marzocco engineers -- Eric Perkunder and Dan Urwiler -- set up a factory in South Seattle and designed an innovative espresso machine called Slayer that allows baristas to customize the pressure as they pull a shot, giving them further control over the quality and flavor of each drink. Meanwhile, the La Marzocco plant in Italy continues to manufacture nearly 4,000 machines a year and remains a popular choice for coffee shops everywhere.

The 2000s also welcomed the area's first black-owned coffee shops, beginning in 2008 when Berhanu Wells opened Tougo Coffee in the Central Area neighborhood. Ten years later Efrem Fesaha, sourcing coffee exclusively from Africa, opened Boon Boona, a cafe and roaster in Renton that became a hub for the local East African community. Fesaha mentored others on such things as coffee sourcing and sustainability, as well as the importance of providing community spaces. In 2020 one of his proteges, Darnesha Weary, opened Black Coffee Northwest in Shoreline. Other successful Seattle coffee businesses were also established in the early 2000s, including two coffee-based donut chains -- Mighty-O Donuts and Top Pot -- in 2002, and Herkimer Coffee in 2003.

Despite all the changes and corporate wrangling that have taken place, the Seattle region reveres its rich coffee history. In 2023, Cafe Allegro in the University District -- which first opened in 1975 -- is the city's oldest continually operating coffeehouse and Bargreen's Coffee, which has been roasting coffee in Everett since 1898, is the state's oldest independent roaster still in operation. The iconic Espresso Vivace cart on Broadway closed on April 30, 2023 -- the same year that the company, which continued to operate at other locations, celebrated its 35th anniversary. But the former Stewart Brothers Coffee roasting facility on Vashon Island, which had closed after Seattle's Best Coffee was purchased by Starbucks in 2003, later reopened as the independently owned Vashon Island Coffee Roasterie and continues the original mission of producing top-quality coffee.