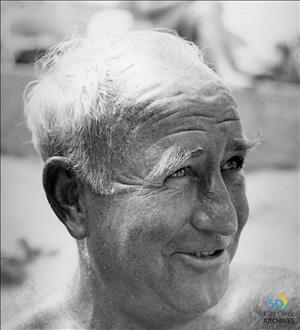

Author Max Miller (1899-1967) spent years as a newspaper reporter before becoming a literary sensation in 1932 following publication of his first novel I Cover the Waterfront, a book later made into a movie. While the book is set in San Diego, California, Miller drew heavily on memories of growing up iin Everett. He continued to write about these formative years in subsequent novels, numbering 27 in all. The following article, written by historian David Dilgard (1945-2018) of the Everett Public Library, was published in 1983 in the Journal of Everett and Snohomish County History and was updated by Margaret Riddle in 2020 for use on HistoryLink.

Max Miller and Everett

Everett didn't make much fuss over the death of Max Miller in December of 1967. By then he had been a "Former Everett Resident" for about half a century. The local newspaper noted only his former residency and his immensely successful book I Cover the Waterfront, a book about San Diego, the place he made his home, the place he died. It was a short obligatory obit, as short and dispassionate as the ones that appeared that week in the New York Times, Time magazine and Newsweek spreading news that this successful writer of books was dead. But the news held special sadness for those in Everett, and not just for those who had known Miller personally. Among the copious output of a career that spanned more than three decades were books that spoke at some length of the author's boyhood in Everett. Three times he turned his attention and skill toward youthful memories and the resultant chapters comprise an extraordinary portrait of life in "Milltown" between the turn of the century and World War I, probably of literary merit but unquestionably of enduring value to those with an interest in Everett's past.

Max Carlton Miller, who wrote more memorably than almost anyone about hometown Everett, wasn't born there. Son of William (1851-1934) and Bessie (1854-1932) Miller, he came into the world at Traverse City, Michigan on February 9th of some year at the turn of the century, probably either 1899 or 1901. When Max was still a baby, the family relocated in Everett where Mr. Miller had established a grocery. The family home at 2303 Summit Avenue was at the end of a streetcar line deep in the city's Riverside district.

Max was the youngest of the large Miller clan, a seemingly privileged position that seems to have allowed him to delay entering school because his mother couldn't bear to part with her last born. When he finally marched off to class, it was a short four-block trek to Garfield Elementary School.

Little time was wasted securing gainful employment for the littlest Miller who was working for his father as a delivery boy and selling newspapers in the red-light district on Market Street while still in short pants. His parents would have disapproved of the latter endeavor. They attended Grace Methodist Episcopal Church, a block from their home, and Max went to Sunday school there. But Max concealed his activities as a newsboy from them, musing nonetheless over sin and damnation and the fate of the ladies who always gave such generous tips when they bought papers from him.

Max shared in the local football mania, rooting for Enoch Bagshaw's (ca.1885-1930) legendary Everett High teams and dreaming of a future heroic role in these contests. He and his buddies haunted the rail yards, fascinated with the Japanese who lived in a shanty town there and they played at "Old Orchard" below the ridge at the east end of 20th Street, where a freshwater spring was a recurring source of amusement, in part because of the hoboes that frequented the spot. On a sand bar in the Snohomish River the youngsters played pirate and cannibal games. Sneaking free rides on the electric streetcars or simply helping the conductor turn his car around for the return trip were among the joys of Riverside life early in the century and of course there were circuses and parades. Once Teddy Roosevelt (1858-1919) rode down Hewitt Avenue, waving to the crowds and, to the bewilderment of little Max, saluting the fallen women of Market Street as well. Accompanied by an older brother, Max even ventured on occasion to the other side of town. If you were careful to hide your clothes from pranksters, you could swim in the bay near the flour mill. These childhood pleasures were perused in a lumber and shingle mill town where men marched off daily to the mills and boys were expected to follow. The risk of injury or death in the sawmills seemed an integral part of the rite of passage to manhood.

About 1913 Max Miller's halcyon days in Everett were interrupted briefly by a sojourn in western Montana, on a stark homestead outside Conrad. Here his father attempted to farm a bleak tract with the help of a son or two and so it was that Max left a world of sawmills for one of tumble weeds and life in a 14-foot square tarpaper shack. Needless to say, the new environment was just as rich for an imaginative youngster as ever it had been.

It was decided to send Max back to Everett to finish school. During his high school years he worked for Bert Daniels (1871-1942) at the Vienna Bakery, delving between tasks into his first high school class reading, When Knighthood Was in Flower. The bakery was at 1409 Hewitt, across the alley from the Wisconsin Building at Hewitt Avenue and Hoyt Avenue, where the offices of the Everett Tribune were located. Most mornings editor Addison R. Fenwick (1860-1945) partook of rolls and coffee in the back of Daniels' shop and it was there that Miller was initiated into professional journalism when Fenwick hired him to report high school activities for an Everett Tribune column.

Predictably Max was active on the high school newspaper as well and was to serve as editor-in-chief of the yearbook his senior year, but his high school career was put on hold when the United States entered World War I. He enlisted in the Navy in July of 1917, just after completing his junior year. (Contradictions concerning Miller's year of birth may well originate in a fib to a recruiter on this occasion).

Following duty on a wooden sub chaser in the Caribbean he was discharged in December of 1918 and reentered Everett High, graduating the following June. Among his classmates was Seton Miller (1902-1974), no relation, who was to seek his fortune in Hollywood as an actor and then as a screenwriter, eventually winning an Oscar for his original screenplay Here Comes Mr. Jordan in 1941. Seton Miller wrote the class prophecy in 1919, casting Max as a critic "on a big daily paper".

In the fall of 1919 Max Miller enrolled in the University of Washington, where he enthusiastically entered into fraternity life, edited the campus daily and the UW magazine Columns. He skipped graduation ceremonies in 1923 to cover the Jack Dempsey-Tommy Gibbons fight in Shelby, Montana for the Seattle Star. Miller had sparred as a teenager with Everett welterweight Travie Davis (1897-1943) and had a broken nose to show for it and had some experience in the ring during Navy training camp.

With Davis' help he had picked up extra cash boxing in Seattle smokers, all of which combined with his journalist skills to make him a prime candidate for a career as a sports reporter. But this apparently seemed a bit too predictable and too close to home for an adventurous young writer just out of college.

He sailed instead for Australia where he found a job with the Melbourne Herald. Then restless again, Miller launched his own expedition to Malaita, an island in the Solomons near Guadalcanal said to be inhabited by head-hunting cannibals. Barely ashore, he was hit in the leg by a little spear and shortly thereafter was on his way back to Everett, nursing an infected leg wound and a nasty case of malaria.

Resting up at the family home, Miller worked his experiences into copy. Though the Tribune had become the Everett News while Max was in college, Addison Fenwick was still editor and there was no problem securing temporary employment with his old boss. A series of specials from the pen of the young adventurer appeared in May and June of 1924, most of them very loosely based on the malaria episode, but some of which pondered Miller's childhood and his own hometown. Miller comments at the end of one of them that it is "the outline for the novel I shall not write," but the ideas explored in the News essays of 1924 were eventually to develop into the autobiographical fiction his Everett readers treasure most.

Roy Pinkerton (1886-1974), the Seattle Star editor who hired Miller to cover the Dempsey-Gibbons fight, had moved to a job with the San Diego Sun. Broke and eager, Miller showed up on his doorstep and was hired to report the waterfront beat for $30 a week.

During his years with the Sun, Max Miller made the acquaintance of Charles Lindbergh (1902-1974), becoming something of a press agent for him during the days of obscurity that preceded his transatlantic flight. There was also an excursion to China and a wedding -- Miller married Margaret Ripley in 1927. But the regular fabric of the writer's life consisted of gathering news around San Diego harbor and longing to become a recognized author of books. A number of flowery romantic novels brought only rejection slips. His wife quietly suggested that the best things he had written were the short personal pieces he had never submitted for publication. A collection of this sort of material was sent to E. P. Dutton where a reader named Louise Nicholl took a personal interest in it. She began working with Miller, polishing a selection of episodes and assembling them into a book. The work in progress was I Cover the Waterfront.

Published by Dutton in the summer of 1932, the book was a smash. It went through eight printings in six months and reviewers loved it. The New Yorker called it "thoroughly delightful." The Los Angeles Times critic felt it had "the touch of something dangerously like pure genius." "Distinctive, original, unusual, fresh in tone and manner …" said The New York Times. United Artists wound up with the movie rights, though the completed film starring Claudette Colbert and Ben Lyon had a screenplay that understandably bore little resemblance to Miller's plotless collection of sketches. The promotional song, which also had only the title in common with the book, was to become a jazz standard performed by the likes of Billie Holiday (1915-1957), Artie Shaw (1910-2004), and Louis Armstrong (1901-1971).

If sudden and extravagant success implies a literary fluke or flash in the pan, such was not the case with Miller, whose feet were firmly on the ground. He diligently applied himself to his craft, drawing upon the basics he picked up as a reporter. Years later when explaining the unpretentious style for which he was known from the very beginning, Miller said that during his newspaper days he had learned to pare his prose down to essentials "in self defense ... to avoid the humiliation of watching the copyreaders do it for me, and to me."

Miller was clearly drawn to autobiography from the outset but initially his feelings about home and family were troubled ones that, in the context of his adult life and career, seemed to evoke previous little nostalgia. The tenderness evident in the books which isolate and explore his childhood, through a child's eyes, as a time and place far removed, is missing when Miller the adult attempts to resolve his own mixed responses to his parents and the place where he grew up. The conclusion of Waterfront finds him returning home to sort things out and his second book He Went Away for a While voices bitter resentments concerning his parents' narrow religious views and their refusal to accept his desire for more education. Once he had tasted the outside world, the writer found that home had become "something to dread."

The second book was another success, exhausting four printings the first month. Drawn deeper into the theme of his own youth, Miller devoted his next work to those early years in Everett and Montana. The Beginning of a Mortal may read to some as straight autobiography but it should be recognized as autobiographical fiction, a literary treatment based on fact but not necessarily constrained by it. Miller needed that distance and freedom in his attempts to coax truths from his own experience. He was to return to motifs from childhood more than once during his career and readers seeking insight into the writer's thinking and his approach would do well to compare Beginning with Shinny on Your Own Side, published 25 years later. Stories involving the streetwise older kid ("Slats" Shoemaker in one book, Willie Carter in the other) who moves into the perilous world of adulthood; the crusty houseboat woman who was always afoul of the law but an ally of the youngsters (Mrs. Defoe in Beginning and Mrs. Higgleby in Shinny); the hobo encountered near the railroad tracks (nameless in the early version, Edmond Joots in the later one); all these and others quite obviously versions from the same models. Miller takes control over his own early memories and transforms them. When he does it well, we come away moved, savoring potent impressions of the place, the people and the time.

While many Americans, journalists and otherwise, were suffering becalmed careers or outright unemployment during 1932 and 1933, Max Miller's life had become a dazzling whirl of new experiences and opportunities. During this period in which his first three books appeared, he sat in for a summer for New York World Telegram and accepted an invitation from producer Walter Wanger (1894-1968) at Columbia Pictures to come to Hollywood and try his hand at screenwriting. He was getting $44 a week as a reporter and the offer of $250 a week from Columbia looked good. He took a leave of absence from the Sun and spent six weeks trying to figure out what was expected of him. A book called For the Sake of Shadows, which he published a few years later, gave some details of his uneasy stay in the film capital.

His temporary leave of absence from the newspaper became permanent when he returned to find his old editor had been replaced. Max and Margaret settled into the cottage they had built at La Jolla and the ex-newspaperman contemplated a future as a self-employed author. He began to write about the experience of becoming a homeowner and the paradox of that new security coinciding with the insecurities of self-employment. Another loosely strung series of brief episodes, The Second House From the Corner appeared in 1934 and several printings were quickly sold out.

Although Everett was certainly not the central topic of Second House, it contains several interesting references to the old hometown. Miller's ambiguity about his origins surfaces early on. When asked by a neighbor what state he was from, he tells him, "I can't quite tell" and a few pages later, upon further consideration, he says, "Well, I once lived in Montana ..."

This vagueness about where he came from is a bit at odds with the ensuing flashbacks, all set in Everett. Chapter 4 finds him recalling a black postman on Riverside and Chapter 5 revolves around a sea serpent experience in Port Gardner Bay. His old classmate Seton Miller puts in an appearance in Chapter 13 and one of the book's highlights is an Everett story in Chapter 16. The wife of a prominent mill owner is encountered at a party and Miller unfolds a tale of humiliation concerning his days as a delivery boy for his father's grocery when he tumbled into a lady's flower bed with a load of potatoes.

During the balance of the thirties, Miller was a model of discipline and industry. The introspective, ruminative works were interspersed with and finally eclipsed by projects utilizing the reporting skills he had honed at the San Diego Sun, books about the Arctic and the Bering Sea, Mexico and Southern California. When World War II began, Lt. Max Miller, USNR, went to the South Pacific and the North Atlantic. Four books documented the conflict, with royalties going to naval welfare funds. The last of these, The Lull, harks back to Miller's earliest efforts, being an encounter of the veterans' struggle to readjust to civilian life. Then, back with Dalton after 10 years, he wrote another work in the same contemplative mode called The Town With the Funny Name, about La Jolla. Miller's childhood turns up in spots but his Montana memories dominate. The single Snohomish County reference is a disgruntled comment about pollution of the rivers there.

In 1949 Dutton published No Matter What Happens, the closest thing to straight autobiography that Miller was to write. His disarmingly candid manner and swift flow of the narrative make it quick, enjoyable reading and the opening chapters are full of Everett anecdotes not to be found elsewhere in his work.

During the early Fifties he did two more books about the Navy and a travel book about Baja, California. Miller spent a good deal of time researching a history of the American petroleum industry which appeared in 1955. In 1958 Doubleday published what can be described as an expanded reprise of The Beginning of a Mortal. Titled Shinny on Your Own Side (a reference to a school-yard game played at Garfield Elementary), it contained two Montana stories originally published in the New Yorker as well as substantial new Everett material, including stories about Teddy Roosevelt's visit, Billy Sunday (1962-1935), the circus, an ill-fated outing to Lake Stevens and an aunt's scandalous slide down the pole at an Everett fire station. Somewhere between Miller's two previous memoirs in treatment, Shinny is a marvelously entertaining book.

Slowed by age and illness, Miller was to produce one more travel tome on California and an historical piece about Denver before his death in 1967. Over a 30-year career his personality and style won the affection of a large and loyal audience. Today, with his 27 books out of print, his name is unfamiliar to the majority of the reading public. Occasionally a modest revival of interest develops and a small but passionate group of devotees (most of them bibliophiles) exists. What remains constant is Miller's status as a gifted, disciplined writer who, during the course of a long and productive career, left a very special printed legacy for the town where he spent most of his childhood.