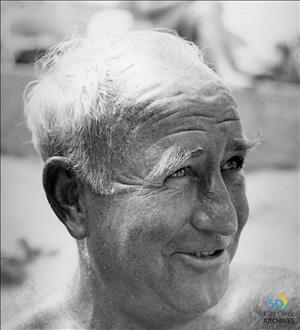

Author Max Miller (1899-1967) spent years as a newspaper reporter before becoming a literary sensation in 1932, following publication of his first novel, I Cover the Waterfront, a book later made into a movie. While the book is set in San Diego, Miller drew heavily on memories of growing up in Everett, and he continued to write about these formative years in some of his later works. Before fame, Miller wrote several features for his hometown newspaper, testing material drawn from his boyhood. The following essay by historian David Dilgard (1945-2018) of the Everett Public Library was published in 1983 in the Journal of Everett and Snohomish County History and was updated by Margaret Riddle in 2021 for use on HistoryLink.

A Byline in Everett

Recovering from the ill effects from an adventure in the Solomon Islands, Max Miller returned to Everett in 1924 and wrote a series of pieces for the Everett News. The name of the paper had changed during his years at University, but Miller found his mentor Addison Fenwick still editing, and Fenwick gave the young journalist a byline and feature status for seventeen pieces which ran from May 17 through June 8.

Playing the role of wounded adventurer for all it was worth, Miller concocted some fanciful episodes about cannibals of "Bozangalong Island," which bore little resemblance to his own experience. There were some odd attempts at humor involving the city's recently erected totem pole. Of substantially greater interest to us today are several essays about Miller's childhood, the earliest extant efforts by the author in that direction. Three of them are reprinted here.

Though the writer had a fair amount of professional experience at the time, his work for the News in 1924 seems very green and awkward in places, but the reminiscences are unquestionably groundwork for books that saw publication many years later. There are episodes here that he was to rework more than once (the hobo spring, cannibal island, and hats on the fence), as well as apparently unique material which didn't resurface in the books, notable the memory of swimming at the flour mill. These tentative steps toward autobiography (or what he called at the time "the novel I shall not write") predate The Beginning of a Mortal by a full decade and, in spite of the author's doubts, were clearly prototypes for the mature autobiographical fiction he was to produce later in his career.

"The Absolute Dominion of Four Cannibals"

The following column appeared on the front page of the Everett News on Sunday, May 18, 1924:

MAX MILLER GOES BACK

TO FIRST CANNIBAL DAYS

They Were Spent on Sandbar of Snohomish

River Beneath Banks of Old Orchard

Tribe of Four Lived the Life There

By Max Miller

There is no definite day nor no definite summer. All seems clear enough now. Even clearer, I could say, as each birthday subtracts another mile sign from here and The Land From Where We Came. All is clear enough now I say, the sandbar in the Snohomish beneath the banks of Old Orchard. Old Orchard -- Five apple trees and one pear tree all gone wild even then, -- but now! One stump left, I do believe. One stump left and it is still trying to put out green shoots.

Go to Old Orchard, near the foot of Twentieth Street, and for yourself see. Not a tree, and only this lonely stump, and grass ankle-deep. Today women visit there even on weekdays. But eighteen years ago -- when Ernie, Pete, Floyd and I were cannibals on the sandbar – no one came to Old Orchard but hoboes. They came regularly. They slept there.

Too, occasionally Sunday School picnics used the grounds because a spring was handy for making lemonade. Is the Sunday School teacher still alive who remembers sending me to the spring for a bucket of water? Then here is the confession:

I was only five or six then, you know, and the spring seemed so tiny and cramped in that sunken barrel while the Snohomish appeared so broad, spacious and airy, that unbeknown to you I took the water from the river. And you used it. The whole picnic used it.

So if any of you or yours have been hurried into Eternity because of that frightful deed, please be patient because in twenty, thirty or forty years I will join you anyway, and I can tell you what you missed by not staying on earth longer. And in that way we can be friends again.

The sandbar formed on the Snohomish at this point then, even as now, when the tide was out and the Cascades had surrendered all their snow freshets.

This sandbar was the absolute dominion of four cannibals. They ruled the sandbar from tip to tip and each day for a week at a time the four cannibals killed, kicked, slaughtered, tortured and clubbed the billions of whites who likewise each day for weeks at a time tried to land their battleships on the sandbar.

Pete was the best cannibal. Given an even start he could always swim the channel first to plant his bare foot plump into the freshly washed sand of the sandbar.

"See" he would say planting his foot harder and deeper than was necessary, "See". This was his way of informing the world at large – Ernie, Floyd and I – that "Know all men by these presents, I, Pete McGhie, am today crowned king of the cannibals -- as usual".

We let him retain this satisfaction in his own mind, yet each of us knew, we too were king of the cannibals. All of us. And why not? Each of us was as naked as the other. All of us were on a par when it came to hating the Whites the most. What fools they were not to be cannibals. Kick them again. Torture them, do them the favor of killing them. We did. We did until the tide would start to come in again, dissolve our sandbar, bit by bit, and drive the four of us ashore.

Ashore if we dried ourselves at all before dressing, this drying was done with our shirts. Underclothes? Never! Only city dudes were supposed to wear them. If the sun was too low – Floyd had his wood box and Pete and I had our cows – the only way to return home was to pretend never to have been away from home. For those were the days when mothers had only one interpretation for wet hair, the incorrect interpretation.

"Ah, so you have, have you"? – fingers feel our damp hair – "Right upstairs till father comes home, young man. Right, no, first fill the wood box"! And how we would fill the wood box. When the wood box was too filled, we would put in stanchions of wood and pile against the stanchions.

Up, up, up would go the woodpile, up, up, up – but no leniency even if we started directly into the evening and afternoon chores without first presenting ourselves. That practice was even more fatal. It made our mothers suspicious, and with suspicion came detection, and with detection came a certainty – and the father came home, always, just at that sunset time when disturbed young voices carry far and wide and entertainingly over street and fence. And those were my first cannibal days, 18 years ago.

Early Lessons in Education

This column ran in the News (Page 8) on Wednesday, May 28, 1924:

MY HISTORY OF EVERETT

SCHOOL DAYS AND EARLIER

By Max Miller

The Everett with which I am concerned came into being on a winter morning only some 27 years ago. At dawn of that morning, I glanced out of my bedroom window beneath a pack of quilts and saw snow clinging to the clothesline. This was my earliest memory. And you older citizens, to prove anything existed before I saw snow on the clothesline, needs must show books and pictures and tell incidents ... Yet how am I to know but what you may all be combined against me just to show me a good time. And that after all the world and Everett actually did begin from the moment the clothesline was packed with snow.

All this occurred in a house on Riverside, still standing. Then we moved across a wilderness ever so far by skid roads, trails and wagon ruts (not roads) to what is now 23rd and Summit. No, this is not an autobiography. It is just my history of Everett.

But unlike most histories, my history includes only those things of which I myself am positively certain. By that time, I had heard a number of strange and weird things – with names outside the scope of "mama" and "papa" and "house". I had heard of a vague, far off place hundreds and hundreds of miles away where my elder brother on certain afternoons would go swimming because "the water in the bay is warmer". The Everett Flour Mill under that, evidently, is where all the swimmers of all the world dressed and undressed. One day in reckless defiance to the parental laws, he took me to the bay swimming. He took me under the Everett Flour Mill. And it was so, all the swimmers of all the world dressed and undressed there.

The sawdust, I remember as we unchanged our clothes, was ankle deep and I had a craving to remain inside our shirts and our stockings for ever and ever. Then my brother gave me a brand-new sentence, one I have cherished in semi-mystery to this day: "Ditch your clothes", he instructed, piling his own under a log, "or they'll make you chaw raw beef". Who was "they" and what was "chew" or "chaw" raw beef"? Evidently, though, the terns were connected with swimming or a part of it. The only sample I saw at the time was a boy struggling to untie two dozen or more knots from a shirt (his own). The shirt, to add to the duration of the knots, evidently had been soaked in bay water. So the boy, to assist with the untieing, was using his teeth. From that moment on, then, the world appeared a dangerous place, for mother and father had never done that to our shirts at home. They had never made us "chaw raw beef".

The world those days was divided into two hemispheres: Bayside and Riverside. Also in the conversations of the elders entered an absolutely puzzling word, "Seattle". It came in every once in a while. I heard of a thing called "America" and also of another thing called "War" the youngsters in the next block played it. But "Seattle"? So one day I cornered my mother by the screen door:

"Ma, if Everett is "America", what is "Seattle"? Is Seattle what America goes to war against? She did not answer. She could not. She hurried into the kitchen where the others were. And so the question was left entirely up to me, and has been ever since.

As for the school system, I was sitting by the telephone when it happened. The principal of the Garfield School had phoned. My mother answered and this is all I heard: "Yes, Mrs. Miller speaking – Mr. Sherwood? Yes. Oh, no, no. I couldn't send him this semester. Yes, I know, but really Mr. Sherwood, he's only five. He's the only one left of the eight, the only one not in school. Really Mr. Sherwood, the house will seem so lonely. Yes, I'm teaching him myself. When will he be six? Oh fully two more weeks yet".

So the next day with my hair parted identically like my older brothers parted theirs, I strutted the four blocks of 23rd Street and became a member of that great race of people who must raise their hands before speaking.

In the following months of school, I learned the following definitions:

A schoolyard fight is two bodies of something-or-other surrounded by many more something-or-others and it is better to be one of the something-or-others than the something-or-others when the principal appears.

Love (usually "Loves"): a word written on sidewalk or fence with stolen classroom chalk and ordinarily written between a masculine name and a feminine name.

Teacher: Something to be sketched with pencil or chalk. The sketch must show all ten fingers and all ten toes arranged fan-shape after a certain design of flyswatter.

"Prof": That part of a school building that has an office. On one's first summons to the office, the "Prof" plays with his whip publicly all during the conversation, but does not use it. On one's second summons and thereafter, the "Prof" does not show his whip at all until he has extracted from his guest a dozen eager "Yes, I'll be goods". Then as the guest, being fully satisfied that he has been very fortunate for a sinner, is about to leave, the "Prof", reaching into his cabinet remarks, "Well, I'm glad to hear you'll be good but just wait a minute … "

"Sister", that thing that tells "Ma" what happened to you at school.

"The Novel I Shall Not Write"

This column appeared on Page 2 of the News on Thursday, May 29, 1924:

MY HISTORY OF EVERETT

PASSING SHOW RECALLED

By Max Miller

Certainly I can see them … their faded hats, stained with sawdust and slivers -- the hats seem to be walking along the top of our high board fence -- Hats, hats, usually brown, but always faded, usually punctured in the crown, always drooping in the rim -- all going to the sawmill.

The first whistle -- leave Washington once and see how you miss the sawdust whistles for telling time --came then at six. It was signaling the wives more than the husbands. "Up you come", commanded the whistle. That's the stuff. Kindling in the woodbox, kindling the man brought home last night on his shoulder. Kindling in the woodbox. Kindling for mush, hot cakes, coffee -- lots of coffee. Up!"

Away went another brown hat to the sawmill, then came noon. Lunch pails, tin ones, black ones. Tin ones with tin cups for a cover over a tin partition for coffee -- no thermos bottles then. To have hot coffee use the mill fire or have a son old enough or out-of-school enough to bring the lunch warm, to the mill at noon. The noon whistles screeched "Half through, Half through, Half through"!

At night, an early darkness most likely, the early darkness shadowing the hats, usually brown, always faded, usually punctured, usually drooping, returning atop the board fence from the sawmill.

Two, three more years and our school vacations changed from swimming in the Snohomish -- changed to becoming hats passing the board fence to the sawmill. So better to have someone to cook the mush, the hotcakes, the coffee. Better to work at the sawmill. So better to sons to wear our hats when we are finished with them -- to wear our hats to the sawmill. On, on, on -- and that is the outline for the novel I shall not write.

On Collecting Max Miller

Readers who are interested in Miller’s books that deal with Everett and Snohomish County may want to seek out the trio that concern his early life there: The Beginning of a Mortal (Dutton, 1933), No Matter What Happens (Dutton, 1949) and Shinny on Your Own Side (Doubleday, 1958). These books were mentioned by historian Norman Clark in his book Mill Town, which brought them to the attention of book dealers and collectors in the 1970s. Miller’s popularity has faded over time and in 2021 first editions can be found for low prices. Beginning of a Mortal is more sought after since New York Social Realist artist John Sloan illustrated the book, making it highly collectible.

Miller’s other autobiographical works may be of interest: I Cover the Waterfront, He Went Away for A While, The Second House from the Corner, The Man on the Barge, For the Sake of Shadows, The Lull, The Town with a Funny Name. Of these, the easiest to find, and still the most popular, is Waterfront, which has had several reprints since its first publication. In 2021 most of Miller’s books can be found used, with prices ranging from $5 to $55, depending on edition and condition.