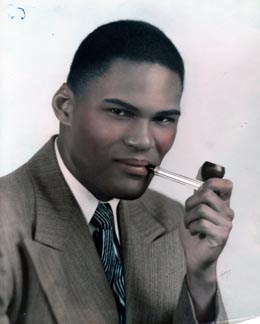

Carl Maxey was Spokane’s first prominent black attorney and an influential and controversial civil-rights leader. He was born in 1924 in Tacoma and raised as an orphan in Spokane. He overcame an almost Dickensian childhood to become a household name in Eastern Washington, beginning in the 1940s when he won an NCAA boxing championship for Gonzaga University in Spokane. Later, after becoming a lawyer, he threw himself into Washington state's civil-rights struggle, defending a black citizen's right to get a haircut, teach in the public schools, join a social club, and buy a house in any neighborhood. He went to Mississippi to participate in the Freedom Summer of 1964 where he worked with Stokely Carmichael (1941-1998) and Martin Luther King Jr. (1929-1968). Through a long and flamboyant career, he defended the Seattle Seven in a scandalous anti-Vietnam-War protest trial; ran against Senator Henry (Scoop) Jackson (1912-1983) for the U.S. Senate on an anti-war platform; defended notorious serial rapist Kevin Coe and Coe's mother Ruth; and was nominated for the Washington State Supreme Court. He was loved by many for his unwavering stands against racial discrimination, and resented by many others for upsetting the status quo. He died in 1997 when he shot himself in the head in his bedroom in Spokane. The New York Times headlined his obituary: “Type-A Gandhi.”

A Motherless Child

Maxey never knew his mother or his father. He was born in Tacoma on June 23, 1924, to Marian Alfred, age 13, in Tacoma and soon given up for adoption to Carl and Carolyn Maxey of Spokane. (Previous versions of this essay listed Elizabeth Cooper as the mother, as stated in a Superior Court adoption order. However, new adoption records came to light in 2016 that made it clear that Elizabeth Cooper was actually the grandmother -- Marian Alfred's mother). The Maxeys named the baby Carl Jr. The elder Carl Maxey, a sometime railroad worker, sometime pool-hall janitor, disappeared when the child was 4, leaving Carolyn Maxey with no means of support. In January 1930, the boy was sent to the Spokane Children's Home as a "charge of the county."

Carolyn Maxey died soon after of heart failure, alone, in a downtown apartment. Now the 8-year-old Carl was truly an orphan. His best friend at the Home was Milton Burns, the only other "colored" orphan, as the Home called them, although Milton was mostly American Indian. One of Maxey's enduring personality traits had already emerged by this time: A burning desire to protect the underdog. Maxey was big and Burns was small, and Maxey didn't allow any of the other kids to pick on his friend.

“My first recollection of Carl was that he was always protecting me,” said Burns.

No Place for Children

However, Maxey couldn't protect Burns or even himself from the abuses of the orphanage after the lights went off. The children, including Maxey, were regularly pulled out of bed at night and beaten by the assistant superintendent, said Burns. In 1935, when Carl was 11, some of the older orphans went to the police and accused the superintendent of having “improper relations” with some of the boys.

Within two days, both the superintendent and the assistant superintendent had tearfully confessed to having sexually abused some of the boys. Within three days, both men had pled guilty and were behind bars at the state prison in Walla Walla, where they each served five years for sodomy. Neither Maxey nor his friend Burns were involved in the scandal.

“Thank God they didn't like black kids,” Maxey later said.

From Nowhere to Nowhere

Yet Maxey and Burns suffered for it anyway. The scandals, covered extensively in the press, sparked a general round of housecleaning at the Spokane Children's Home. The board hired a new superintendent and instituted reforms. One of those reforms: The board voted to kick Maxey and Burns out of the Home.

Maxey said he was never told why, but he always suspected that the scandal was the excuse and that racism was the underlying motive. Decades later, when Maxey dug up a copy of the Board minutes for October 8, 1936, he read the words in black and white:

"It was moved ... that the two colored boys, Carl Maxey and Milton Burns, be returned to the County, having been in the home for years. Motion carried. It was moved ... that the Board go on record as voting to have no more colored children in the Home from this time forward."

“They threw us out,” Maxey later said, just before his death. “It sure as hell says that. And the incident that precipitated it was sexual misconduct, all involving white people. So if you wonder where some of my fire comes from, it comes from a memory that includes this event.”

Before long, the two boys ended up at the refuge of last resort, the Spokane County Juvenile Detention Center.

“We hadn't committed any crime except that of being boys too young to take care of ourselves,” said Maxey.

The Faith of Father Byrne

After a few months, both boys were rescued from the Juvenile Detention Center by a remarkable figure: Father Cornelius E. Byrne. Byrne offered to board the two boys at his Indian mission school at the Sacred Heart Mission, 50 miles away in DeSmet, Idaho. Almost all of the students were Coeur d'Alene Indians. Maxey had never been to a place where the white students were a minority. The effect was liberating. For the first time in his life, Maxey began to feel as if he had a home.

“I haven't known any fathers in my life,” Maxey said later. “The closest thing I had to one was that Jesuit priest.”

Maxey began to thrive. He became a conscientious student and a talented athlete. He was big, strong, and fast, and soon he was the star of the school's baseball, basketball, and football teams. Father Byrne also taught the boys the science of boxing. He arranged boxing matches for his boys at the rough logging and mining camps in the area. Maxey fought his first boxing match at the age of 13. His opponent was 33. Maxey beat him. Maxey left the mission school at age 15, after Father Byrne had granted him one last favor. He had arranged a full-ride scholarship for Maxey to Gonzaga High School, Spokane's Catholic prep school, associated with Gonzaga University.

Fighting Segregation

Soon after graduation from Gonzaga High School in 1942, Maxey entered the service. He wanted to be a pilot, but the U.S. Army Air Corps was all-white. He became a private in a medical battalion. The Jim Crow laws and the hateful attitudes he encountered at Southern army bases shocked Maxey. He began to realize that his purpose on earth was to fight for justice and equality. He later said that his “social awareness was born in the outrageously segregated Army.”

When he arrived back in Spokane in 1946, he was immediately confronted with evidence that his hometown was no haven from segregation. As he got off the bus in full uniform and walked into the station cafeteria, he was denied service. He resolved, at age 21, to become a lawyer. He attended the University of Oregon briefly and then came back to Spokane in 1948 to attend Gonzaga University’s law school on a boxing scholarship.

Maxey went undefeated in all of his collegiate boxing matches for two years, compiling a 32-0 record. King Carl, as he was nicknamed, frequently had to go easy on his opponents so he wouldn't hurt them. Maxey derived a lesson from that.

“Nobody ever thinks about that -- not knocking somebody out you're clearly superior to,” Maxey once said. “That's a far more decent deed than trying to addle somebody's brains.”

But at the end of his second year, he still had one more tournament to face: The National Collegiate Boxing Championships in 1950 in State College, Pennsylvania. Tens of thousands of spectators, as well as reporters from all over the country, then witnessed what the tournament referee later called “the most masterful piece of boxing” he had ever seen. Maxey defeated Michigan State’s Chuck Spieser by one point in the finals. Maxey was crowned the nation’s collegiate light-heavyweight champ and Gonzaga had earned a tie for its first NCAA championship of any kind. When the boxers arrived home by plane the next day, 1,000 students and alumni were waiting on the tarmac at Spokane's Geiger Field. The fans broke through the State Patrol's restraining lines and rushed the plane. Maxey and the other boxers were hoisted atop shoulders and carried through the screaming mob.

The Ring of Social Justice

He never fought another bout. He retired from the ring to devote his energy to his law classes, where he was struggling. He pulled his grades up and graduated in 1951. Then he became the first African American in Spokane to pass the bar exam. The city still did not have a black doctor or dentist. Nor did it have a black teacher, a situation that Maxey immediately set out to rectify.

Eugene Breckenridge, a black man, had applied to be a teacher with the Spokane School District with what appeared to be sterling credentials: Four years service in World War II as an Army sergeant; a bachelor's degree in chemistry with a minor in biology; a master's degree in education from Whitworth College, a private liberal arts college in Spokane; and an award for being the college's outstanding student teacher. Yet he was not deemed qualified to teach math and science to seventh graders at Havermale Junior High. His application languished for two years while Breckenridge made a living as a window-washer. Maxey immediately went on the offensive. He went to the superintendent, and smothered him with a mix of friendly persuasion and principled argument. Maxey said the superintendent came to "recognize the morality" of Maxey’s argument.

Yet morality was apparently not enough for the school board, which had to approve all of the superintendent’s hires. When the school board balked, as they had done with earlier black applicants, Maxey threatened to slap them with an NAACP lawsuit. The board finally relented and hired Breckenridge.

This case ended the color bar once and for all in the school district; by 1969, there would be 20 black teachers in the district. Maxey was especially proud of the difference this made in the life of Eugene Breckenridge. Sixteen years later, Breckenridge was named the Washington Education Association's Educator-Citizen of the Year, its highest honor.

Challenging the Status Quo

Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, Maxey continued to take on cases that would challenge the racial status quo. He was instrumental in ending two pernicious real estate practices: red-lining and restrictive covenants. He helped end the racial restrictions at the city’s all-white social clubs by using a clever legal strategy: He threatened to take away their liquor. In a series of lawsuits, he argued that private clubs could discriminate all they wanted, but not if they applied for a public right, the right to sell liquor. Most clubs eventually chose liquor over discrimination.

In 1963, Maxey played a key role in what came to be known as the "Haircut Uproar." A Gonzaga University student named Jangaba A. Johnson, a Fulbright scholar from Liberia, was refused service in John M. Wheeler’s downtown Spokane barbershop. Johnson’s fellow students took it on as a cause. Thirty-five students, 29 of them white, showed up a few days later to picket the barbershop. The protest aired on the national broadcast of CBS News the next day.

Maxey promptly filed an official complaint to the State Board of Discrimination. A month later, Maxey argued the case before a meeting of the board's tribunal. The tribunal deliberated less than three minutes before ruling against the barber and ordering him to cease discrimination.

Later in 1963, Maxey gained national exposure for taking on the case of Will Cauthen, a young black fugitive from Georgia. Cauthen had been convicted in 1959 of murdering a white gas-station attendant. He escaped from prison just days before his scheduled execution. Cauthen hid out as a farm hand under an assumed name for three years near Warden, Washington, until the FBI finally tracked him down and arrested him.

Maxey represented Cauthen in his extradition hearings and helped uncover information showing that Cauthen’s murder trial in Georgia had lasted less than a day, no blacks were allowed on the jury, and that Cauthen’s lawyer had been participating in his first, and only, trial. Maxey referred to the trial as “pitiful” and a “perfunctory execution.” Governor Albert Rosellini (b. 1910) eventually denied Georgia’s extradition request, thus sparing Cauthen’s life.

In 1964, Maxey volunteered with two other Washington state lawyers to provide legal services for the Mississippi voter registration drive known as Freedom Summer. He helped free Stokely Carmichael and hundreds of other volunteers from jail and he walked the streets with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Maxey was shocked by the conditions he saw there and later described Mississippi as the “tail end of America.”

Maxey in Politics

In the 1960s and 1970s, Maxey threw himself into politics. He ran, unsuccessfully for several local offices. He became presidential candidate Eugene McCarthy’s (1916-2005) state spokesman in 1968, and witnessed firsthand the turmoil and violence of the 1968 Democratic Convention in Chicago. By this time, Maxey had become staunchly anti-Vietnam-War. When a Gonzaga University student body president was arrested for shouting, “Warmonger!” at vice-president Spiro Agnew during a speech, Maxey successfully defended him.

In 1970 Maxey ran a quixotic primary race for U.S. Senator against one of the nation's leading hawks, Washington's longtime Democratic Senator Henry "Scoop" Jackson (1912-1983). Even though Maxey was a lifelong Democratic, he had turned against Jackson over his support of the war. The campaign turned vitriolic; Maxey called Jackson a “Napoleonic little senator” and a “political schizophrenic.” Maxey hoped to get 10 percent of the vote against the man he called “the senator from Boeing.” Maxey got 13 percent.

Trial of The Seattle Seven

The statewide attention Maxey received in the campaign helped him to land the most controversial and heavily publicized case of his career: The trial of the Seattle Seven. The Seattle Seven were members of an anti-war group called the Seattle Liberation Front, which in 1970 organized an anti-war demonstration in front of Seattle's Federal Courthouse. When police intervened, the protest turned violent. The courthouse was vandalized and its windows smashed, and then the angry demonstrators raced downtown and smashed storefronts all through downtown Seattle.

The seven defendants, including at least one former member of the radical group the Weathermen, were charged with conspiracy to riot and destroy public property. The defendants hired Maxey because, as Seattle Seven member Susan Stern (1943-1976) later wrote, "he was the most respected lawyer in the state of Washington, and he was black." He was one of four defense lawyers.

The trial began in Tacoma in November 1970. U.S. District Court Judge George Boldt was determined that the trial not become a repeat of the chaotic Chicago Seven trial the year before. Yet about two weeks into the trial, most of the defendants were slapped with contempt citations for repeatedly disrupting the proceedings.

When the defendants returned to court on the contempt charges, all order broke down. The defendants tore up their contempt citations and threw them into the air. One walked up to the bench and threw a Nazi flag at the judge. Federal marshals eventually waded in, triggering a wild, fist-swinging melee. Marshals started dragging the screaming defendants out of the courtroom. The gallery also erupted in fighting, and a number of onlookers were forcibly evicted. Some of the defense lawyers were also dragged out of the courtroom, but not Maxey. Maxey did his best to keep his clients from joining the melee, because he knew it would just get them into deeper trouble. The trial was never resumed, and the conspiracy charges were eventually dismissed. However, every defendant except one served jail time on various contempt charges stemming from the fracas.

Boldt reprimanded the other defense lawyers and singled out only Maxey for praise: “Mr. Maxey did everything he reasonably could to prevent or restrain his clients and other defendants from misconduct.” Maxey later called it a “riotous, disgraceful courtroom event” and “the most difficult case I have ever tried, because of the personalities of the defendants.” Stern, for her part, said that Maxey treated her throughout the trial like a “lovable but unruly daughter.”

Cases and Many Causes ... and Criticism

During the 1970s and 1980s, Maxey became the region’s most sought-after divorce lawyer, a branch of law that Maxey equated to war. Yet his law firm was committed to devoting 20 percent of its time to pro bono work (legal work done free of charge) and he continued to take on civil-rights causes. Five presidents, beginning in 1963 with John F. Kennedy, had appointed him to the Washington State Advisory Committee to the U.S. Civil Rights Commission.

He also took on high profile criminal cases, including those of Kevin and Ruth Coe. Kevin Coe was accused of being Spokane’s notorious “South Hill Rapist” and Maxey came in late in the case during the sentencing phase. When Kevin's mother, Ruth Coe, was caught on tape attempting to hire a hit man to kill the judge and prosecuting attorney, Maxey became her lawyer. She was convicted but Maxey was credited with getting her a surprisingly light sentence: one year in jail with work release.

By the 1980s Maxey began to attain an elder-statesman status in his profession. In 1988, retiring Washington Supreme Court justice Willam Goodloe publicly recommended Maxey as his successor. Maxey’s detractors protested the nomination, accusing him of turning every issue into a racial issue. Governor Booth Gardner chose the only other black nominee, Charles Z. Smith (1927-2016).

Yet even as the public at large grew to admire Maxey’s legacy, one particular critic sounded increasingly bitter. That critic was Maxey himself. As his trademark mane of hair turned whiter, Maxey became increasingly discouraged about what America, and he himself, had accomplished.

He told interviewers that his work had not made much difference to the people in power. He said he never got the respect he deserved for keeping things non-violent. It fostered, he said, one overriding feeling: cynicism.

He said, “the whole damn country is a bunch of Archie Bunkers.”

A City Mourns

Then, on July 17, 1997, just a day before he intended to announce his retirement from the courtroom, came the shocking news: Maxey had ended his own life at age 73 with a gunshot to the head in his Spokane home.

The city mourned as it had for no other figure that decade. The Superior Court judges formed a black-robed honor guard at his memorial service. The Spokesman-Review published 12 stories about him over the next few days.

Maxey left behind no note. His wife, Lou Maxey, reported that he had been upset at the thought of retirement. One of his sons, Bevan Maxey, noticed a distinct change in his father’s mental state about a week before his death. Yet his doctor had never diagnosed Maxey with any ailment besides high blood pressure. The coroner ruled the death a suicide and performed no autopsy.

His oldest friend, fellow-orphan Milton Burns, visited Maxey just a few days before his death. He said that Maxey seemed exhausted. Maxey told Burns he had been in the lawyer business for 46 years and needed to get out. So maybe Carl Maxey was simply worn out. Maybe, after fighting his way up from nothing, after fighting his way to a national championship, after fighting in the courtroom for every underdog, after fighting to change an entire culture, he just couldn't fight anymore.

Whether he knew it or not, Maxey had been the catalyst for important changes in the racial climate and in the anti-discrimination laws in Washington. Today, when students of Gonzaga Law School enter the law library, they pass by a bronze bust of Carl Maxey. The inscription reads: “He made a difference.”