Carson Dobbins Boren and Mary Ann Kays Boren were among the first Anglo-Americans to settle in King County. With their infant, Livonia Gertrude Boren, known as Gertrude (1850-1912), they left Illinois to travel West on the Oregon Trail with the Denny Party. They arrived on Alki in Seattle on November 13, 1851. The following spring, they among others homesteaded in what would become downtown Seattle. The Borens had two more children, William Richard (1854-1899) and Mary Louise (1857-1926). Carson and Mary Kays Boren divorced in January 1861. Carson served as King County's first sheriff. Later he prospected for gold, constructed telegraph lines for Western Union, and was a carpenter, farmer, and hunter. There is much we do not know or understand about Mary Boren. We have a few facts but no first-hand account. She married three more times and had another daughter, Lydia Blakeney (1869-1921). During the 1860s and 1870s she largely lived in Oregon. She kept the name Blakeney but divorced this last husband in 1884. She returned to Seattle to live the rest of her life, mostly with her daughter Lydia. Carson lived his last years in King County, first with son William and later with daughter Gertrude.

Carson Boren: Early Years

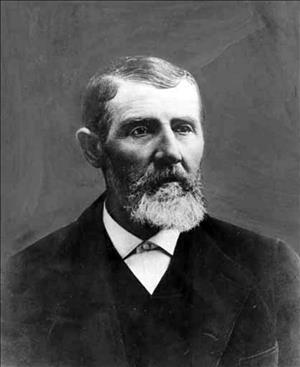

Carson Boren, born at Nashville, Tennessee, on December 12, 1824, was the second child of Sarah Latimer Boren (1805-1888) and Richard Freeman Boren (1788-1828). His father was a cabinetmaker and a circuit-rider Baptist preacher. By age 9, Carson had lived in at least five places as the family moved between Tennessee and Illinois. When Carson was 3, in 1828, his father died. Sarah moved the children back to Tennessee to live with her father. In 1834 they moved to Knox County, Illinois. Sarah acquired land and raised her three children in a log cabin on the Illinois prairie. Winters were frigid. Heating the cabin required a large log to be constantly burning, so large it required three people to place it in the fireplace.

In Knox County, the Borens met the Dennys. This was momentous event for the history of Seattle. The families merged, traveled west together on the Oregon Trail, and were among Seattle's first settlers. In 1843, Carson Boren's oldest sister, Mary Ann (1822-1912), married Arthur Denny (1822-1899). In 1848 Carson's mother married her second husband, John Denny (1793-1875), father of Arthur and David. After the two familes arrived in Seattle, David Denny (1832-1903) married Carson's youngest sister, Louisa Boren (1827-1918), in 1853. These were two very entangled, intermarried family.

Back in Illinois, Carson Boren married Mary Ann Kays on February 18, 1849.

Mary Ann Kays: Early Years

Mary Ann Kays was born on November 6, 1830, in Putnam County, Indiana, to Elizabeth (Bracken) Kays (1810-1871) and William Kays (1804-1891). In 1834 the Kays family of six moved to Knox County, Illinois, where they developed a prosperous 225-acre farm. By 1850 the Kays had 60 swine, 68 sheep producing 135 pounds of wool, and harvested 2,000 bushels corn and 400 bushels wheat.

Mary and Carson started a family on a 50-acre farm. They had two horses, two milk cows, seven sheep, and 30 swine, and harvested 800 bushels corn, 100 bushels oats, and 25 bushels potatoes. Nine months later the Borens had their first child, Sarah (December 17, 1849-January 3, 1850). The infant lived for only 17 days. She is buried in the Cherry Grove Cemetery in Knox County. On December 12, 1850, Gertrude was born.

Overland Journey to Oregon Territory

The 50- to 80-acre farms of the Borens, Arthur Denny, and John Denny were located close to one another. When the families gathered during the frigid winters of 1849-1850 and 1850-1851, they must have read letters and newspaper reports of settlers arriving in Oregon Territory (which included Washington). A Denny genealogy states that John Denny was the "leading spirit ... determined to leave the rigorous climate of Illinois" (Denny Genealogy, 53). In early fall 1850 news arrived that the United States would grant married couples arriving in Oregon from 1851 to 1855 a 320-acre homestead, if they lived on the land for four years. The decision was made to go West.

On April 10, 1851, the Borens with 5-month-old Gertrude joined the Dennys and left Cherry Grove in prairie schooners, crossed the plains, and on June 21, 1851, reached the summit of the Rocky Mountains. The most arduous part of the journey was to come. Two months later they arrived in Portland, 134 days after leaving Illinois. In Portland the party met William Bell (1817-1887) and family. In early November, the Borens with the others boarded the schooner Exact and sailed from Portland to Alki, arriving on November 13, 1851.

First Cabin in Seattle?

Many sources incorrectly state that Carson Boren built the first cabin in Seattle. Carson built the third cabin. This confusion arises over Mary Boren's symbolic act of laying the cabin foundation.

On March 23, 1852, Carson Boren and David Denny left Alki Point for the Willamette Valley to retrieve cattle they had brought overland and wintered there. On April 3, William Bell and family, accompanied by Louisa Boren (Carson's sister) and Mary Boren (Carson's wife) and the child Gertrude, moved from Alki Point to Bell's homestead claim in the future Belltown neighborhood of Seattle. On this land Bell initially put up a camp "like an Indian of slabs and mats," he explained years later. "Lived in it 2 weeks before I got a cabbin built." He added, "Borren moved over [to his claim] in som 3 weeks" (Bell to Bancroft, June 9, 1878). Also on April 3, the recently arrived David Maynard (1808-1873) moved onto his homestead claim in what would later be Pioneer Square and the International District.

In early April, while the Bell and Maynard cabins were being constructed, Mary Boren apparently became concerned that some settler would jump the Boren claim before Carson returned. So Mary Boren and her sister-in-law Louisa Boren, with their family dog, had Native Americans paddle them from Bell's camp to Boren's proposed homestead claim just north of present-day Pioneer Square. After landing on the beach, the two women hiked through the forest to the "chosen spot ...[T]hey cut with their own hands some small fir logs and laid the foundation of a cabin" (Blazing the Way, 59). This established the presence of the Borens on the proposed homestead claim.

Carson Boren and David Denny returned from the Willamette Valley with their cattle, probably during the third week in April 1852. On April 27, 1852, Carson purchased from Charles Terry's store on Alki six pounds of nails -- no doubt used to construct his cabin -- and a wood stove. This was 24 days after Maynard and Bell had moved to their homestead claims. By that time their cabins were built or close to completion.

In filings made concerning his 320-acre homestead, Boren stated that he settled on the claim on May 13, 1852. This is likely the date the Boren family moved into their completed cabin, making it the third cabin built in Seattle.

Indigenous People vs. Settlers

In the winter of 1852-1853 the Oregon Territorial Legislature created King County -- on indigenous land -- and appointed Carson Boren as its first sheriff. He served in that role until September 1854. In April 1854, a corpse presumed to be that of a missing white man was found south of Lake Union. Four Native Americans (three were Snoqualmie) were accused by another Native American of killing him. A mob of white settlers lynched two of the accused. A third under suspicion was placed in a locked room in Sheriff Boren's cabin (there was no jail). The mob broke in and dragged him out and were about to hang him when Boren intervened and saved the man's life.

During the Treaty Wars, Carson Boren served in the militia from October 1855 to July 1856 as second sergeant.

About spring 1857, two Native Americans broke into a general store in Seattle and stole money and goods. The white settlers reacted brutally. An undated statement signed by 30 settlers including Arthur Denny, Henry Yesler (1810-1892), and David Maynard stated, "We ... are in favor of whipping the two Indians, cropping their heads, and making them leave the place forthwith" ("Notes by the Way"). Boren whipped one of the men 25 times and King County Sheriff Hillory Butler (1819-1896) whipped the other 25 times.

Carson Boren, Miner

From the time of his divorce, Carson was mostly gone from Seattle. He may have visited, but no evidence exists that he lived in Seattle from 1862 to 1867.

The Seattle Intelligencer published an interview about Carson's prospecting exploits, including his 1861-1862 journey to the gold rush in east central British Columbia along trails that were "difficult and dangerous in the extreme." It stated that "Mr. Boren was one of the early Cariboo miners ... He traveled and mined all over this country to the north of us and knows what he has seen and what he is talking about" (Intelligencer, December 30, 1879, p. 3). During 1879 and 1880, Boren and his son William were at the gold mines of Ruby Creek, a Skagit River tributary, about 40 miles south of the Canadian border.

Boren, with three mining partners, established the Seattle Consolidated Claims along a quarter mile of Canyon Creek, a tributary of Ruby Creek. Theirs was one of some 50 mining claims along this creek. By early July 1879, they had completed a 500-foot-long ditch and constructed a head dam, sluice boxes, and rockers to sort out dirt and rocks from the gold.

On February 13, 1880, after wintering in Seattle, Boren and some 15 miners took passage on the steamboat Josephine for the Skagit River. Travel to the mines was not easy. It took more than a day for the steamer to reach Mount Vernon on the Skagit. The miners would then hire Native Americans with their canoes to take them, their equipment and food on a four- to five-day journey 100 miles up the Skagit. At the end of the canoe trip, the miners, with 60- to 80-pound packs, had a rough four-day hike covering 50 miles and crossing the Skagit three times.

On April 3, 1880, the Canyon Creek miners met at the Boren cabin to form the Canyon Creek [mining] District. They agreed on how to establish claims and resolve claim disputes. They also established consequences for individuals who jumped a mining claim or broke into another miner's cabin.

In August it was reported that $1,000 in gold dust from the Skagit was arriving weekly in Seattle. In late August 1880, the Seattle Fin Back reported, "C. D. Boren ... has just returned from the Skagit mines, and in order to make us feel bad, exhibited some very fine specimens [of gold]" (Seattle Fin Back, August 30, 1880, p. 3). Boren headed right back and two months later returned from the Skagit a final time. The gold rush in Canyon and Ruby creeks, which had involved some 1,500 miners, was over. Later a reporter called C. D. Boren "one of the few successful Skagit River Miners" (Snohomish Eye, September 13, 1882).

The Telegraph Line

After prospecting in the Cariboo region in the mid-1860s, Boren worked for the Western Union Telegraph Company. The company had already built a telegraph line from the East Coast to San Francisco, and was intending to extend it north to Alaska, across the Bering Strait, across Siberia, ending in Europe. This stretch was called the Collins Overland Telegraph Line. Reaching Portland in March 1864, the telegraph company crossed the Columbia River and continued north, clearing a corridor through the forest, setting poles and stringing telegraph lines. The line reached Olympia on September 4 and Seattle on October 25. The firm continued north, laying cables across the inland waters. It reached British Columbia a year later.

Working for the telegraph company, Boren spent the entire summer, probably in 1865, in British Columbia helping to guide a 100-mule pack train. The pack train and its crew picked up supplies left by steamboats at Skeena River and traveled hundreds of miles back and forth making deliveries. Boren claimed they hauled more than 40 tons of telegraph wire and insulators. This was likely done to stage material for the 1866 construction season.

After exploring north British Columbia for the telegraph company, Boren returned to the coast in the vicinity of Sitka, Alaska. He caught a telegraph company steamboat to Puget Sound. In 1866 a competing company succeeded in laying a telegraph cable across the Atlantic to Newfoundland. Contruction of the Collins line was halted and the telegraph line north of Quesnel, B.C. was abandoned.

After his return to Seattle, by 1870, Boren lived in a residence occupied by John M. Lyon (1840-1918), the Seattle agent for the Western Union Company. It's possible that Boren was working for the telegraph company to help maintain the line in Western Washington.

The Lives of Mary Ann Kays Boren

In May 1852, when the Borens moved into their Seattle cabin, Gertrude was 17 months old. Two more children were born there, William Richard on October 4, 1854, and Mary Louise on May 3, 1857. Mary Ann later had another daughter, "Lydia Kays" or Lydia Dell Blakeney, born in Oregon on January 18, 1869. Lydia was not a Boren.

The Boren Divorce

On May 23, 1853, Carson Boren and Arthur Denny recorded one of the first plats in Seattle (Boren and Denny's Addition), and this marks the beginning of Seattle as a town, with a planned commercial center, building lots, and streets -- not farmland. On February 15, 1854, Boren filed a second plat (Boren's Addition).

In the late 1850s, domestic issues began to trouble the Boren family. An early account stated that Carson Boren "sold his claim early at a great sacrifice and became a roamer, and, therefore, did not share in the up-building of the town" (Bass, 118-119). In April 1855 the Borens sold half their homestead, including almost all of both plats. In March 1859 they sold the remaining half, receiving $1,100 for both sales. For the next year they sold most of the remaining land and livestock -- five horses and two cows.

We do not know when the Borens separated. King County assessment rolls completed by early spring 1860 show the family still living together. But by July 1860 Mary was living with her three children in Steilacoom.

On November 22, 1860, Mary filed a complaint in the district court suing Carson for divorce and custody of their three children. The case was dropped because on December 6, 1860, Mary Boren's lawyer, who was a member of the legislature, introduced a bill to the Territorial Legislature Council (equivalent to today's Senate) to "dissolve the bonds of matrimony existing between Carson D. Boren and Mary his wife" (Journal of the Council of the Territory of Washington, beginning December 3, 1860). The council voted on December 13, 1860, yes, four; no, two; and not voting, three. Opposing the practice of legislative divorces, councilmember Arthur Denny did not vote on his brother-in-law's divorce. Four days later, the House of Representatives passed the divorce bill 14 to 10. It was one of 17 divorce bills the Territorial Legislature passed that session. All this goes to show that the early settlers did divorce, and that some divorces became the business of the entire Territory through its legislative body.

What happened to the three children? Mary lost custody. They were returned to Seattle, though Carson was absent from Seattle for most of the 1860s. The three children were raised by the three Denny families with Boren wives. Arthur Denny and Mary Boren Denny raised Gertrude. David Denny and Louisa Boren Denny raised William. John Denny and Sarah Boren Denny raised Mary.

Mary Boren's Later Marriages and Divorces

Six or seven weeks after her divorce, Mary Boren married Elihu Shea in Steilacoom. They lived on a King County farm. This marriage lasted only nine months. The Territorial Legislature passed the bill for this divorce on January 24, 1862. On November 24, 1864, Mary Boren, listed as Mary Kays, married carpenter Edward J. Northcutt (1830-1904). We don't know what happened to this marriage, but five years later (by 1870) Mary was living in The Dalles, Oregon, as Mary Kays with her 1-year-old daughter, "Lydia Kays," born on January 18, 1869. We do not know who Lydia's father was. Northcutt was living in Salem with a new wife.

Next, on November 6, 1872, Mary Kays married John W. Blakeney (1823-1902) at The Dalles. Blakeney ran pack trains and operated a hauling service. The Dalles, located along the Columbia River, was the main shipping point to Eastern Washington and Oregon. Lydia Kays's name became Lydia Dell Blakeney. By 1880 John Blakeney and Mary were living in Napa, California. According to the 1884 divorce action by John Blakeney, Mary left Napa in May 1880, "to parts unknown by the plaintiff." In September 1881 she was in The Dalles, and "from thence she went to Seattle and since that time John Blakeney has never heard from her and he doesn't know her present [1884] wherabouts" (Wasco County Court Case, Oregon State Archives). On March 27, 1884, the judge finalized that divorce.

To summarize Mary Ann Kays's marriages:

- Carson D. Boren, 1849-1861

- Elihu Shea, March 1861-January 1862

- Edward J. Northcutt, 1864-pre-1872 (no divorce record located)

- John W. Blakeney, 1872-1884

For the rest of her life, Mary used the surname Blakeney. The King County Census lists her in 1881, but in the mid-1880s her whereabouts are unknown. From 1887 onward she lived in Seattle. On February 27, 1889, her daughter Lydia married David A. Marshall (1863-1937), an engineer for the Columbia and Puget Sound Railroad. During the final decade of her life, Mary lived with Lydia and David.

Mary Ann Kays Boren Blakeney died on June 21, 1905. The funeral was held at Lydia's home. It was largely attended, her obituary stated, "by some of the old pioneers of the city" ("Mrs. Blakeney Buried"). She is buried in Lake View Cemetery in a grave inscribed M. Boren Blakeney.

So much remains a mystery. What was she like? What were the reasons for her several marriages? How did a unmarried woman in the late nineteenth century survive? What kind of mother was she? She wanted custody of her children, but lost it, although she stayed with her last child, Lydia, for her entire life. What sort of relationships did she have with her first three children and with the Dennys and Borens? We just don't know.

Carson Boren, Carpenter

From the late 1860s to the mid-1880s, when not prospecting, Carson Boren lived in Seattle. Most directories and census enumerations list him as a carpenter or miner. There was much to build. From 1870 to 1885, Seattle's population increased from 1,107 to 9,687. In the 1876 Seattle directory, Boren is listed as a ship carpenter. He might have worked on the 152-foot-long, three-masted barkentine Katie Flickinger. During the first half of 1876, about 40 men worked on the ship.

Carson Boren's Later Years

In the spring of 1883, Boren, nearing his 60th birthday, went on a three-month prospecting tour, probably his last. In 1885 William made a 160-acre homestead claim on federal land just opened for homesteading near the future town of Duvall. Carson went to live with William on the farm, which had a horse and two or three cows.

After William Boren's 1899 death, Carson lived with his daughter Gertrude. In about 1910, they moved to the Ravenna neighborhood of Seattle. In his final decade, Boren was honored as a founding father in many commemorations of Seattle history. On November 13, 1905, on Seattle's 54th birthday, he was one of three surviving adults who participated in ceremonies to unveil the monument at Alki Point honoring the landing of the Denny Party. More than a thousand people attended.

Six years later the 18-story Hoge Building on the northwest corner of 2nd Avenue and Cherry Street was dedicated. This was the location of the 1852 Boren cabin. The Seattle Times reported that "the aged pioneer ... is still hale and hearty and and can shoot as well or better than many of the younger men of his acquaintance" ("New Hoge Building is Opened to Crowd of 10,000 People").

Gertrude died on June 3, 1912. Carson Boren, his death certificate suggests, was devastated. He died 10 weeks later, on August 19, 1912. Both are buried at Lake View Cemetery.

Gertrude's Life

Gertrude Boren was carried west over the Oregon trail as an infant. She lived with her parents in Seattle until she was 10. After her parents' divorce she lived with Arthur and Mary Denny until the early 1880s, when she was in her early 30s. She attended the first classes at the Washington Territorial University, which opened on November 4, 1861. Forty-seven students, ages 6 to 16, were enrolled for the five-month term. She was a longtime member of Seattle's First Methodist Church, and a charter member (1866) of the Seattle Independent Order of Good Templars, which promoted abstinence from alcohol. In 1873 she sold Wilson Sewing Machines. In the early 1880s, Gertrude and her brother William lived together a short distance from the Arthur Denny family.

In November 1883, the Washington Territorial Legislature gave women the right to vote for the first time. On June 20, 1884, 33-year-old Gertrude Boren, along with her father, registered to vote. But in 1887 the Washington Supreme Court ruled women's right to vote unconstitutional.

For about 25 years, starting in the mid-1880s, Gertrude, William, and Carson lived on their farm, spending some of that time in Seattle. In the spring of 1912, Gertrude was making plans for a reunion of the nine survivors of the 24 who had landed at Alki. Her plans ended abruptly when she died of a heart attack on June 3, 1912. Her funeral was held on her namesake street, Boren Avenue. She is buried at Lake View Cemetery.

William's Life

After his parents divorced, 6-year-old William lived with the David Denny family, where he remained until the early 1870s. A Denny biographer stated, "David taught William Boren the precepts of Christianity and temperence along with the skills of the woodsman and hunter" (Newell, Westward to Alki, 96). William enjoyed hunting trips. He also sometimes accompanied his father on mining trips. In 1885, he made his homestead claim for his farm.

On October 28, 1886, with Gertrude bearing witness, William at age 32 married Ellen Douglas Pinkerton (1870-1967), the 16- or 17-year-old daughter of a nearby homesteader. They had one child, Roland Kenneth Boren.

William's wife, father, and sister helped tend the farm. William came to a sad end. An early account stated, "During his ranch life he was waylaid, basely and cruely attacked, and beaten into insensibility by two ruffians. Most likely this caused the fatal brain trouble from which he died in January [19], 1899 ..." (Blazing the Way, 303). He is buried at the Monroe IOOF Cemetery.

Mary Louise's Life

When the Borens separated, Mary was 3 years old. After the divorce she lived with her paternal grandmother, Sarah Boren Denny. From 1862 until at least 1872, Mary attended school at Washington Territorial University; a teacher described her as industrious, with perfect deportment. On August 27, 1874, at her grandmother's home, 16-year-old Mary married 21-year-old Samuel Thomas Denny (1853-1913), witnessed by Carson Boren. Samuel, a distant cousin of Arthur and David Denny, arrived in Seattle in 1870, and for many years worked as a steamboat captain. The family grew to seven children born from 1876 to 1895.

On January 1, 1926, Mary Louise Boren Denny died at her daughter's home. The heirs donated a family heirloom to the University of Washington -- an old ironware plate the Borens had brought with them across the plains in 1851.