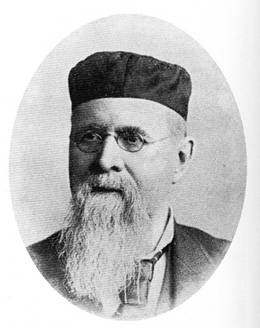

William E. Boone, Seattle’s premiere architect prior to the great fire of 1889, became one of few architects to continue practice after the Panic of 1893. He also designed significant buildings in Tacoma. Boone laid the foundation for professional practice within Seattle in 1894, when he became a founding member of the local chapter of the American Institute of Architects.

From the East Coast

Like many of Seattle’s first architects, Boone was born and educated on the East Coast. Over the years, he moved west from Pennsylvania, practicing in Chicago, Minneapolis, and California, respectively. In 1881, at age 50, he settled in the Puget Sound area. During most of the 1880s, Boone worked with architect George C. Meeker. Both were principals of a prolific firm with offices in Seattle and Tacoma. Among their many works were:

- The Yesler-Leary Building, Seattle (1882-1883) destroyed);

- The Annie Wright Seminary in Tacoma (1883-1884, destroyed);

- The Henry Yesler House, Seattle (1884, destroyed);

- The Territorial Insane Asylum in Steilacoom (1886-1887, destroyed);

- The Toklas and Singerman Building (1887, destroyed);

- Seattle’s South School and Central School (1889, destroyed).

The Yesler-Leary Building became a prominent part of Seattle’s commercial district. For inspiration, Boone looked to contemporary commercial buildings in San Francisco. The design is an example of eclectic Victorian architecture that combined stylistic elements from many historical styles. These buildings were often extremely ornate.

After the Fire

After the Great Fire of 1889, Boone received and completed numerous projects on his own. Boone’s independent works looked much like his pre-fire designs. These continued to combine historical elements and decorative brickwork. One extant Boone building is the Marshall-Walker Block (1890-1891), former location of Elliott Bay Books in Pioneer Square.

In late 1890, Boone’s work changed significantly when he became partners with William H. Willcox (1832-1929). This relationship exposed Boone to new trends in American urban architecture. Before moving to Seattle, Willcox had practiced in New York, Chicago, Nebraska, and Minneapolis-St. Paul. The New York Block (1890-1892, destroyed) reflects contemporary work in those metropolitan centers. The differences between Boone’s Yesler-Leary Building and this later building were dramatic. Unlike the Yesler-Leary Building, which had multi-sided projecting bay windows, and an elaborate roof line, chimneys, and a small corner tower, the New York Block was a solid square massive building with simple lines. The later building had clear hierarchy of floors; the lowest, street level looked heavy and solid compared with the lighter upper levels. The rough, rusticated stone at street level, along with heavy Romanesque (Roman empire-style) columns accentuated the difference between ground floors and upper levels. H. H. Richardson (1838-1886) popularized this kind of commercial building, which became the norm for decades around the turn of the century. The round arches of the New York Block, along with its engaged pilasters (flattened columns that divide the building’s bays) are textbook Richardsonian Romanesque.

The partnership of Boone and Willcox disbanded in 1892. The Panic of 1893 left Boone with little work for the remainder of the decade. In 1900, he began his final partnership with Boston architect James M. Corner (1862-1919); the team produced the first Seattle High School (1902-1903; destroyed) and the Walker Block (1903; destroyed). The Seattle High School, also known as Washington High School and Broadway High School, was the first high school building in the city.

Boone retired from practice around 1910. His life’s work reflects major shifts in commercial architecture at the turn of the twentieth century. His consistency and professionalism helped form the foundation for Seattle-area architectural practice.