Eddie Allen was one of the foremost test pilots in the United States in the 1930s and early 1940s. He flew dozens of different aircraft, including more than 30 on their inaugural flights. He first worked for Boeing between 1927 and 1930, both as a mail carrier and a test pilot. In 1939 he was rehired by the company as a test pilot, and his work eventually focused on the B-29 bomber -- an airplane later used by the United States with devastating effect in World War II. Allen died in 1943 when a prototype of the plane he was piloting crashed in Seattle during a test flight.

Beginnings

Edmund Turney Allen was born on January 4, 1896, in Chicago, the third and final child of Edmund Turney Allen (1856-1913) and Abby Dyer Allen (1856-1931). (Despite having the same name as his father, he did not use the suffix "Junior," even when his father was alive.) He had two siblings, Thomas (1888-1956) and Margaret (1893-1973). His father was a successful physician, but restless. The family moved several times during Allen's childhood, including lengthy stints to Florida and Denver, before returning to Chicago in 1909. He graduated from high school in 1913, but though both his siblings were in college, he initially had little interest in higher education. He worked at a farm for three years before finally relenting to family pressure, and enrolled at the University of Illinois in 1916.

The following April the United States entered World War I, then commonly referred to as the Great War, which had been raging in Europe since the summer of 1914. Allen quickly signed up with the Army and was in basic training by late May. In August 1917, he was selected to participate in the aviator's program in the Army's Signal Corps. He learned to fly in a Curtiss JN-4D, which was commonly called a "Jenny," a biplane with a top speed of 75 mph and a range of 175 miles. He subsequently became a flight instructor, briefly taught advanced aerobatics, and in the summer of 1918 was sent to England to learn British flight-testing techniques. He returned to America just before the war ended in November 1918.

The Flying Postman

In 1919 Allen joined the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA), becoming one of its first test pilots. (This later became the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, commonly known as NASA.) He returned to college, first at the University of Illinois for a year, and then, in 1920, at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) for two years. He married Allene Gregory (1887-1947) in August 1920, but the marriage lasted just a few years. After leaving MIT in 1922, Allen participated in glider competitions in France in a plane that he built himself. However, soon after he was in a serious crash while he was piloting a glider in Germany. The plane flipped upside down and crashed into a tree, and Allen was thrown to the ground. There was some early concern that he would lose a leg, but he recovered. The accident did nothing to deter his love of flight -- he spent two months in 1923 flying an experimental helicopter.

He continued his work as a freelance test pilot for NACA, and subsequently worked as a civilian test pilot for the Army Air Service at McCook Field, Ohio, for a year. From 1925 to 1927 he flew for the U.S. Post Office Department between Cheyenne, Wyoming, and Salt Lake City, Utah. This was before radar was in use, and Allen's plane -- a rebuilt De Havilland DH-4 from World War I -- had no radio. He had only a map and a compass to guide him, and he learned the hard way on one occasion that the compass could sometimes be wildly inaccurate. Huge swaths of his flight path were completely uninhabited, with only an occasional emergency airfield and beacon to guide him. If it was too foggy or cloudy below to see to land, he had to find a break in the clouds and put the plane down wherever he could. In all, he had to make eight forced landings during his two years with the Post Office Department.

In 1927 Allen joined the newly formed Boeing Air Transport and flew as an airmail pilot for a time on its Chicago-to-San Francisco route, but he became more and more involved in test flying. His work with Boeing ended in 1930, and he spent most of the next decade as a freelance test flyer. He worked for Douglas, Eastern Airlines, Lockheed, Northrop, and others, and flew more than 30 aircraft on their first test flights between 1928 and 1943. These included the Douglas DC-2, the Lockheed Electra, and the Northrop Gamma. It has been written that Allen's approval of a new aircraft carried such weight that some insurers required it before they would insure one. Later in the 1930s he began to do more work for Boeing, and he flew its prototype XB-15 bomber on October 15, 1937.

Boeing

The XB-15 was an experimental aircraft that had been conceived as a design study by the U.S. Army to determine the feasibility of building a bomber with a 5,000-mile range. It was a stepping stone for other bombers that would follow over the next few years. The plane was a significant leap in airplane technology, and was the largest, heaviest aircraft built in the United States to that time. It was nearly 88 feet long and had a wingspan of 149 feet, and the 35-ton bomber was able to carry a payload of 4 tons. The Seattle Times marveled: "When plans originally were laid for the model XB-15 [in 1934], airplane engineers who talked of ships with a wingspread of 90 feet were considered daring. The wingspread of the XB-15 is 150 feet" ("Giant Boeing Bomber …").

Allen spoke to The Times that day and explained his philosophy of flight. "Never take a chance," he said. "Most of the testing of an airplane like this bomber is done on the ground before the ship's first flight. We know what the ship will do and just about how it will fly. Our job is seeing that it goes into the air a perfect machine with a perfect crew" ("Giant Bomber's Pilot"). It was this attention to detail that led to Boeing hiring Allen again and again.

On June 7, 1938, Allen took the Boeing's Model 314 Clipper Flying Boat aloft on its maiden voyage, taking off from Puget Sound and landing in Lake Washington nearly 40 minutes later. The Clipper was a long-range, four-engine flying boat designed for long distance passenger flights across the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. It came equipped with dressing rooms, a dining room with catered meals, and seats that could be converted into bunks for long flights. The Clipper served the public only briefly before America's entry into World War II in 1941. The aircraft served as a troop and material transport during the war, but its use was discontinued soon after the war ended in 1945.

On December 30, 1938, Allen took the new Boeing Model 307 Stratoliner up momentarily during a "taxi test" at Boeing Field, in which the plane was aloft over the runway for just a few seconds. This nevertheless delighted a throng of spectators who had come to watch, and it made the front page of the Seattle Post-Intelligencer the next morning. (By 1938, Allen had long enjoyed a sterling reputation nationwide as a test pilot. Many of his first test flights of Boeing aircraft in Seattle were covered by local papers and generated considerable public excitement. Whenever he flew a new plane, a crowd was sure to follow.) The Stratoliner was the world's first high-altitude commercial transport, and it was the first commercial aircraft to have a pressurized cabin.

However, it was the crash of the Stratoliner the following March during a test flight by another pilot that had a more significant impact on Allen's career. After the crash, he argued that there should be more ground research in laboratories and wind tunnels of new designs prior to sending new airplanes into the air. Boeing agreed, and in April 1939 the company hired him to be its first -- and as it turned out, only -- Director of Aerodynamics and Flight Research. With the outbreak of World War II less than five months away, the timing could not have been much more fortuitous.

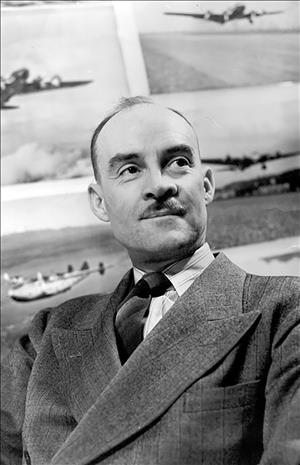

Allen was in the news again a little more than two months later, when he married Florence Brydon (1917-1966) of Seattle on July 1, 1939. They lived near Bitter Lake (in what then was north of the Seattle city limits), and had two children: Florence (b. 1940), who was known by her middle name, Turney, and Edmund (b. 1941). The wedding came as a surprise to his coworkers at Boeing, though it should not have. In his public persona Allen was known as a quiet man, not often one to discuss his thoughts if they weren't work related, and not one to brag. At 5-foot-8, he was slightly below average height and was slender and unassuming, with thinning hair and a small mustache; people were often surprised when they met him by how much he came across as an Average Joe.

The B-29

In September 1939, World War II broke out in Europe. As had been the case in World War I, the United States was not initially in the war, but, as had been the case in World War I, there was a growing sense that the country eventually would be. Allen continued his work at Boeing, taking a new version of the B-17 bomber -- a B-17E Flying Fortress -- aloft for the first time in September 1941 and afterward pronouncing it a "swell ship" ("Boeing Tests …"). But even then work was underway on a bigger, more powerful bomber. The job became more urgent after Japan attacked the United States at Pearl Harbor in December 1941 and America entered World War II. This new plane later became the B-29 bomber.

In 1940, the U.S. Army Air Corps commissioned Boeing to design a new four-engine bomber that could fly higher and farther than the B-17. The first prototype, called the XB-29 Superfortress, was ready for its test flight in September 1942. The bomber weighed more than 50 tons and was powered by four 2,200-horsepower engines, with a range of more than 5,800 miles. It could carry up to 10 tons of bombs, and four of its 12 machine guns could be fired by remote control. Allen took it up on its first flight on September 21, 1942. (Unlike his earlier first flights, this one received almost no publicity because of media restrictions implemented by the military during World War II.) The flight was successful, but many of the test flights that followed did not go as smoothly.

Out of 23 flights by late December, there had been 16 engine changes, 22 carburetor changes, and 19 exhaust-system revisions on the first XB-29. Still, the engines were prone to catch fire. This was vividly demonstrated in the first test flight of the second XB-29 on December 30, 1942, when an engine caught fire while Allen was aloft. The fire spread, and by the time he landed the plane, ribbons of flame were trailing from the right wing and smoke was pouring into the cabin, partially blinding him. Occasional fuel leaks also were an issue, and in conjunction with engine fires, a serious one. Allen recognized the problems and wanted more on-the-ground testing. But now conditions were different. There was a war on. The planes needed to go into production and end the war as fast as possible. Flight testing continued.

Catastrophe

On February 18, 1943, Allen and a crew of 10 men took off to the south from Boeing Field on a flight that was intended to measure level flight performance and obtain engine cooling data. The weather was good, with high clouds and moderate temperatures, and only a 5 mph breeze. Eight minutes into the flight, as the plane passed near Lake Tapps in Pierce County, a fire erupted in the No. 1 engine on the outside of the left wing. It was quickly extinguished, but Allen decided to return to Boeing Field and turned the aircraft around. The wind that day was from the south, and under normal conditions he would have landed the heavy, fuel-laden airplane into the wind, or from the north in this case. Since the threat appeared to be over, he elected to make a loop over Seattle and then turn south into the wind for the landing at Boeing Field. As the plane passed over Renton fire again flared in the No. 1 engine, but at first it was not believed to be serious. Allen continued flying north, passed Boeing Field two or three miles to his west, and flew over the Lake Washington Bridge. Shortly afterward he turned southwest, crossing the shoreline near Madrona Park in Seattle. At that point, witnesses on the ground heard an explosion.

The aircraft quickly lost altitude, dropping parts from its damaged left wing as it went; hose clamps and a deicer valve were later found near 17th Avenue and Jefferson Street. Within seconds, fire erupted on the left-wing spar and quickly spread. In a few more seconds, flames and smoke began pouring into the plane's fuselage. Three men jumped from the aircraft as it passed over First Hill, but the plane was already too low for their parachutes to open, and they did not survive. The bomber passed southwest over part of downtown Seattle, visibly trailing smoke, and then turned south for Boeing Field, three miles away.

By now the aircraft was little more than 100 feet above the ground and still losing altitude. It became apparent to witnesses that the plane was going to crash, and it seemed that in the final seconds Allen came to the same conclusion and was trying to crash land in a marsh just south of the Frye Packing Company on Airport Way. But the bomber clipped a power line just north of the plant and slammed into the building and exploded, killing the remaining eight aviators on board. Twenty Frye employees died, and a firefighter perished fighting the resulting fire the next day. The cause of the second fire, which doomed the plane, was traced to leaking fuel that came into contact with engine components that were hot from the flight.

Legacy

Allen's work on the B-29 bomber cannot be overstated, because it was this aircraft that is credited for helping turn the tide against Japan and for hastening the end of World War II. In recognition of his work, he was posthumously awarded the Daniel Guggenheim Medal for 1943, which is an American engineering award given for a lifetime achievement in aeronautics. His wife, Florence, accepted the medal on April 22, 1944, at the dedication of the Edmund T. Allen Memorial Aeronautical Laboratories at Boeing. This building housed what was described by The Seattle Times as "the nation's fastest large wind speed tunnel" ("Fastest Large Wind …"), capable of generating speeds up to 700 miles per hour. An improved version of the tunnel is still in use today. Finally, Allen was posthumously awarded the Air Medal in 1946 for his work in successfully landing the crippled XB-29 bomber in December 1942, an honor rarely bestowed on civilians.

Though Allen was known for his public reserve, he was less restrained when he was with family and friends. He enjoyed writing them lengthy, evocative letters, and some of them were preserved by his family and published in 2018 by his daughter Turney in her book Eddie Allen -- Test Pilot -- Aviation Pioneer: Letters From My Father. The letters not only provide insight into the days of early flight, they provide insight into Eddie Allen himself. One letter (which he wrote to his mother) is especially illustrative:

"Don't you see that happiness built on such a basis of looking only for the good in life is of the shallowest kind? Then when misfortune comes, the basis of life is swept away and one sinks, floats, or starts all over again. One who sees all of life with, perhaps, an emphasis of sadness or indignation at the evil and folly -- such an emphasis as is evidenced in Jesus' life -- does not build upon a false structure which can be overthrown by misfortune. Some characters who have achieved depth within themselves who see life steadily and see it whole are quite independent of prosperity or adversity, success or failure of their plans, the greatest woe of human life, the defection of a friend -- only such a one can say, I am the captain of my soul. My head is bloody but unbowed by any adversity" (Oswald, 289).