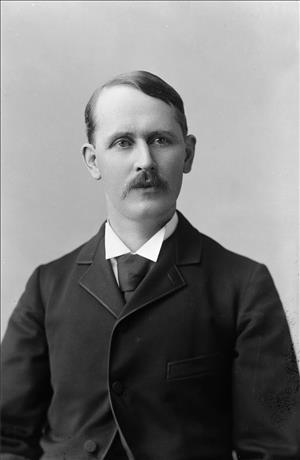

Born in Indiana in 1845 and educated at the University of Michigan Law School, John Beard Allen moved to Olympia in his mid-20s. He served as U.S. Attorney for Washington Territory for 10 years, and then as a territorial delegate. After Washington achieved statehood in 1889, the state legislature elected Allen to serve as one of the state's first U.S. Senators. Meanwhile, Mathilda Allen, his wife, helped lead a drawn-out women's suffrage campaign in Washington, culminating in 1910 with ratification of a right-to-vote amendment in the Washington State Constitution.

Hoosier Roots

John Beard Allen (1845-1903) was born in Crawfordsville, Indiana, the son of prominent physician Joseph S. Allen and Hannah Beard Allen, whose father was an Indiana politician. John was a "Minuteman" as part of the Morgan Raid in Indiana. In 1864 and 1865, he served as a corporal in the Union Army with Company D of the 135th Indiana Volunteers. He attended Wabash College and was a grain dealer for a time in Minnesota, where he moved with his parents. He graduated from University of Michigan Law School and was admitted to the bar in 1869. Allen practiced law in Goshen, Indiana, for a time, and then returned to Rochester, Minnesota, where he was the City Attorney.

By 1870 Allen was in Olympia. According to the Olympian, besides practicing law, he was the librarian for the fledgling Olympia Library, and according to one account, he unfortunately dropped a month’s wages in the form of a watch into Puget Sound. In 1871, Allen married Michigan resident Mathilda Cecilia Bates, described as "a woman of great intellectual ability and unusual force of character" (Early History of Thurston County, 281).

Allen was appointed by President Ulysses S. Grant as U.S. Attorney for Washington Territory in 1875, and served in that position until 1885. Concurrently, he was the reporter for the Washington Territorial Supreme Court from 1878-1885. While living in Olympia, Allen served on the Olympia School Board for several years in the late 1870s and later defended the school board as an attorney just after the turn of the twentieth century. He moved to Walla Walla around 1880, serving as Northern Pacific Railroad attorney east of the Cascades. Elected to Congress in 1888 as the Territorial Delegate (an at-large, non-voting position) from Washington over incumbent Charles Voorhees in a Territory-wide vote, his term ran from early 1889 until statehood in November 1889.

Senator Allen

Allen was elected by the new Washington State Legislature as one of the state's first U.S. Senators along with Watson C. Squire on November 19, 1889. This was ahead of the 17th Amendment, ratified in 1913, which authorized direct popular elections of senators instead of state legislatures choosing senators. Although it was later claimed that Allen worked only for Eastern Washington, during his time in the senate he advocated for a variety of infrastructure projects in Washington including lighthouses, harbor improvements, and the drydock and naval station in Kitsap County. He supported along with Sen. Squire the Lake Washington Ship Canal, a project some thought competed with Columbia River improvements. A January 14, 1893, Morning Olympian article detailed his advocacy for statewide projects. Allen served on Claims, Public Lands, and Relations with Canada committees in the senate.

Because of the way that U.S. Senatorial seats are staggered in classes, Washington’s senators are in Class 1 and Class 3 election years. This meant that Sen. Squire had a two-year first term and Allen initially had a four-year term, from November 20, 1889, to March 3, 1893 (later extended to March 20, 1893). Squire was re-elected by the Washington State Legislature in 1891 for a six-year term, but in 1893, Allen faced a much more difficult road to re-election.

The legislature took up the election early in the 1893 session. Despite a Republican majority in the Washington State House and Senate – 75 Republicans out of total of 112 members (Allen was a Republican) – the legislature was deadlocked through as many as 100 votes. Allen could not muster the 56 votes from Republicans needed for his election. The issue of the re-election arose between Spokane and Seattle sides of the state, with Tacoma legislators siding with Spokane. Spokane delegates were holding out for George Turner from their city, and although Allen was living in Walla Walla, legislators from the two sides of the state were at odds. When the legislature adjourned without electing a senator, Governor John McGraw (1850-1910) appointed Allen. However, the U.S. Senate refused to seat Allen as part of long-time unwritten rule that the senate would not recognize a gubernatorial appointment as a result of a legislature deadlock. Senators from Montana and Wyoming, also appointed by their governors, were refused seating by the Senate that year. So without Gov. McGraw calling a special session (the legislature met by law only every two years), the state was without two U.S. Senators from 1893-1895. In 1895 John Lockwood Wilson was finally legislatively elected to serve out the vacant six-year U. S. Senate term to 1899.

Meanwhile Allen joined the prestigious Seattle law firm of Struve, Allen, Hughes and McMicken and was considering another senate run when he died in 1903. John B. Allen School in Seattle, first built in 1904 with an additional building in 1917, was named in his honor. The school officially closed in 1981 and is now operated by the Phinney Neighborhood Association.

Mathilda Allen's Fight for Equal Rights

Mathilda Cecelia Bateman (1848-1921), a teacher from Michigan, married Allen in 1871, and they were living in Olympia that year, according to census records. Almost immediately, she became involved in the women’s suffrage campaign in Washington Territory. In 1871, she was among the 16 women who called for the first Washington Territorial Woman Suffrage Association convention in the New Northwest newspaper. When the Association gathered in November in Olympia, Mathilda Allen was called to be President to officiate at the convention (which included Susan B. Anthony and Oregon suffragist Abigail Scott Duniway). She presided for a time but then deferred to another Olympian, Amelia Giddings. Allen later recalled that she became interested in women’s voting rights because of her interest in equal pay for teachers. She also recalled that she was not sure her husband supported the cause, but found that he did and that he continued to do so throughout his life.

During the November 1871 convention, the Allens dined at the house of fellow Olympia suffragists Daniel R. and Ann Elizabeth White Bigelow (the house still stands in Olympia). Anthony and Duniway also were present at the dinner. Allen continued to be active in Olympia as a member of the Thurston County Women’s Suffrage Association in the 1870s. In 1892, she was elected as the delegate from the Washington State Equal Suffrage Association to represent the state at the National American Women Suffrage Association convention in 1893. She and many other Washington women never forgave George Turner for his role in overturning women’s voting rights in 1884 as a member of the Territorial Supreme Court, and also for his role as counsel in the 1888 Bloomer Case, which again invalidated women’s voting rights in Washington Territory. Ironically, Turner was also the opposition candidate during John B. Allen’s re-election to the U.S. Senate in 1893 in the Washington State Legislature.

Mrs. Allen renewed her acquaintance with Susan B. Anthony when Anthony visited Seattle in 1896. Allen was involved in the creation of the Washington State Red Cross and served as its statewide president at the turn of the twentieth century. A club woman, she was a member of the Seattle Century Club and the Women’s Educational Club.

In November 1910, just prior to the vote to ratify the women’s suffrage amendment to the Washington State Constitution, Allen wrote extensive editorials in both The Seattle Times and Seattle Post-Intelligencer in favor of the ratification. Allen kept an eye on women voting after their enfranchisement, writing in Seattle newspapers about the use of the vote and urging for the federal women’s suffrage constitutional amendment, which passed in 1920.

She also was part of a Seattle group that hosted members of the Congressional Union for Woman Suffrage (CU) in Seattle in April 1916. The CU sent national organizers to enfranchised states on a "Suffrage Special" train to garner support from voting women to pressure Congress for a federal suffrage amendment. CU representative Harriet Stanton Blatch, Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s daughter, gave a speech in Seattle and was part of a procession of 150 cars that toured the city decked out in purple, white, and gold banners. CU delegate Lucy Burns scattered leaflets over the city from a plane. Envoys went on to Bellingham and later to Spokane, where they planted a tree in honor of May Arkwright Hutton.

As a follow up, Allen represented the voting women of Washington at a CU Convention in Salt Lake City in 1916. Delegates from that meeting and the CU were then poised to go on to Washington, D.C., to lobby Congress via the "Suffrage Special." Later in 1916, Allen ran for U.S. Senator from Washington as a prohibition and women’s-rights advocate, but was defeated in the primary. She died in 1921. Both she and her husband are interred at Lake View Cemetery in Seattle.