The 74 acres that comprise Seattle Center have played a pivotal role in the region’s history. The defining moment came in 1962 when the Century 21 Exposition, also known as the Seattle World’s Fair, welcomed more than 10 million visitors over a six-month period. On January 1, 1963, about two months after the fair closed, the City of Seattle took possession of the fairgrounds and began to transform the site into a civic center built on the legacy of the World’s Fair. On June 1, 1963, the site reopened as the Century 21 Center, and a nonprofit corporation called Century 21 Center, Inc., was created to run it. Grounds and buildings were renovated, including the Opera House, Arena, and Exhibition Hall, but debts mounted and the city fired Century 21 Center, Inc., in 1964. For the next 30 years, Seattle Center went through periods of restoration and neglect as the city grappled with how to fund maintenance and improvements. Several master plans were conceived and approved, including a 20-year redevelopment plan implemented in 2008 that focused on meeting the educational, cultural, and entertainment needs of a diverse and vibrant city.

After the Fair

When the Seattle World’s Fair opened on April 21, 1962, few could have imagined how the next six months of media attention, futuristic-themed buildings and exhibits, a Hollywood movie filmed on-site with Elvis Presley, and the excitement experienced by nearly 10 million visitors would transform Seattle from a rather quiet town into an influential Northwest hub. Federal, state, and city funds, along with donations from private investors, underwrote the major elements that characterized the fair -- the Monorail, the Space Needle, and the International Fountain, to name a few. After the lease ended and the fair closed on October 21, 1962, the City of Seattle took possession of the fairgrounds, and the buildings and attractions were readied for their second act.

Century 21 staff included a Postfair Action Committee, and its planning began long before the fair. "Postfair planning had begun five years earlier," Don Duncan wrote in his 1992 book Meet Me at the Center. "During Century 21's six-month run, discussions had intensified -- sometimes exploding into acrimonious debates. Everybody, it seemed, had an idealized blueprint of what the Civic Center should contain. Arts and culture devotees had their agendas. Those who thought survival depending on becoming Disneyland North had another. At least some in the business community made no secret of their desire to see the Center become one more tourist-promoting, money-generating 'industry'" (Duncan, 84).

In October 1962, Paul Thiry (1904-1993), the Center’s principal architect, developed a post-fair plan for the facilities, working with landscape architects and work crews to transform the grounds, using "three acres of grass sod, more than 1,100 trees, 600 shrubs and much ground cover … to create a truly park-like atmosphere" (The First Year, 12). In the end, however, much of Thiry's plan fell by the wayside:

"Thiry proposed: Replacing the Nile Temple. Moving the Monorail terminal from the Center to Fifth Avenue. Building an Olympic Games-sized swimming pool in the Show Street area. Tearing down High School Memorial Stadium to created a parklike entrance to the Center -- with a multi-level parking garage beneath. Constructing a children's center in the Northwest section of the grounds. And creating more grand vistas. Almost none of Thiry's postfair dreams came to pass" (Duncan, 91)

Several temporary structures built for the fair were torn down immediately, and Memorial Stadium was returned to the Seattle Public School District. Meanwhile, the City of Seattle created Century 21 Center, Inc., a nonprofit corporation, and charged it with converting the grounds into a permanent civic center, taking on a $2 million underwriting campaign among Seattle’s business community. Ewen Dingwall (1913-1996), manager of the World's Fair, was selected to lead the organization, and William Straley (1913-1999), president of Pacific Northwest Bell, was named as chairman of the board. "Century 21 Center, still a wobbly fledgling with almost no money in the bank, was 'thinking big' and wagering its future on the community's support. And the surest revenue source of all – a gate charge – was ruled out by a free-admission policy" ("As an Encore ..."). Also rejected was a proposal to reopen streets on the fairgrounds for regular automobile use.

In 1963, the Seattle City Council approved nearly $1.3 million to modernize and enhance the post-fair buildings and grounds. The biggest share, $850,000, went to upgrade the Playhouse, Opera House, Ice Arena, and Exhibition Hall. Smaller amounts funded ornamental fencing and gates, landscaping, and outdoor lighting. Instead of converting the Science Pavilion to a warehouse as originally planned, the federal government signed off on a $1-a-year lease so the facility could be taken over by the nonprofit Pacific Science Center Foundation. The Space Needle, the most visible venue at the fair, remained in the hands of private ownership.

Growing Pains

The transformation from fairgrounds to city center was difficult. "There were many things to do," Duncan wrote. "The city would pay $2.9 million to the state for the Coliseum, and then begin an 18-month-long conversion to ready it for sports, concerts and trade shows ... The Gayway would undergo a $1 million renovation, including extensive tree-planting, and be renamed the Fun Forest" (Duncan, 89). But by October 23, 1963, one year after the fair closed, Century 21 Center, Inc., was $1 million in the red. Among other expenditures, it had spent $190,000 to remodel the National Guard Amory -- including the purchase and installation of the Bubbleator elevator and an update to the Food Circus and International Bazaar -- and $116,000 to transform the Fashion Pavilion into the Fun Circus.

Despite these financial strains, the Center buildings and grounds were popular with residents and visitors, and the Center was seen as a model for other cities around the country. "Some 2,000,000 visitors have enjoyed the Center’s many offerings since its opening nine months ago," wrote The Seattle Times. "National magazines and major newspapers have written about Seattle’s achievements in glowing admiration. At least two other cities are using our success as a blueprint for their own civic centers ... To many Seattleites, one of the finest outgrowths of the Seattle Center program has been the blend of government agencies with private enterprise" ("Seattle Becomes the Festival City").

Less than a year after the fair closed, a campaign was launched to rename the site. Snappy suggestions included Pleasure Island, Pacifica, and Needleland. The Seattle Chamber of Commerce suggested Puget Gardens. Seattle Center ultimately won out, and the fairgrounds officially opened as Seattle Center on June 1, 1963, although some residents took exception to the name, calling it drab and impersonal. "The exciting new center is something very special for Seattle people – it’s a gathering place all their own," read one letter to The Seattle Times. "It is the happy solution to the problem of where to go, what to do, what to see. But the present designation gives no clue to these diversions" ("The Center").

By 1964, the city was responsible for operating the Coliseum, Playhouse, Exhibition Hall, Opera House, and Arena. It also maintained the Center grounds and provided security. Century 21 Center, Inc., oversaw visitor facilities, such as the Food Circus, International Bazaar, and Fun Forest. The nonprofit also developed a seasonal program of concerts and festivals, managed concessions, and created the Repertory Theatre. By the end of 1964, though, the public-private partnership was skating on thin ice. On December 7, 1964, Seattle Mayor Dorm Braman (1901-1980) put forth a proposal to disband Century 21 Center, Inc., and have the city take over total operation. "The corporation was born in turmoil 25 months ago when the city still was intoxicated with the success of the World’s Fair ... Under Braman’s plan, Greater Seattle would assume Century 21’s obligation to repay the underwriters over a long term" ("C-21 Corp. Plagued by Finances ..."). Century 21 Center, Inc., was finally dissolved in January 1966, by which time it was nearly $1 million in the red.

Donald Johnson, who had previously managed the Civic Auditorium, was hired as Seattle Center's first general manager. He held the position for seven years before resigning in 1969. Ed Johnson, superintendent of Seattle's Parks Department, replaced him for a short time, until Mayor Wes Uhlman appointed Jack Fearey (1923-2007) to run the Center in 1970. In his 13 years at the helm, Fearey oversaw a multi-million dollar refurbishment of the site, financed by a $5.6 million tax levy approved by Seattle voters in 1975, and construction of the Bagley Wright Theatre, which opened in 1983, several months after Fearey was forced out by the Seattle City Council. Dingwall then stepped into Fearey's job, and while his tenure was said to be temporary, he stayed until August 1988, when Mayor Charley Royer appointed Virginia Anderson to lead Seattle Center forward.

Anderson was the first woman to run the organization, and perhaps its most dynamic general manager. She would oversee more than $600 million worth of investment in the Center during her 18-year tenure, including the transformation of the Opera House into Marion Oliver McCaw Hall, which opened in 2003. Still, all was not well when Anderson stepped down in 2006. "For all its attractions, including the iconic Space Needle and the perennially popular Bumbershoot festival, the Seattle Center loses money," the Seattle Post-Intelligencer reported. "Many of its facilities are in disrepair, and campus advisers fear a spiral of bad news, with shabby or unkempt grounds discouraging visitors, degrading bookings and ultimately bleeding more red ink onto the books ... At the heart of any discussion about the Seattle Center is a fundamental -- and decades-old -- tension about who should pay for it" ("Heart in Disrepair ...").

The first bond issue for the Center was soundly defeated at the polls in 1967, and another was rejected in 1970. In 1975, voters approved $5.6 million for maintenance but voted down a $23.7 million bond issue for capital improvements. Two years later the Seattle Center Foundation was established to administer charitable gifts, grants, donations, and bequests to the Center. In 1978, voters passed a $19 million bond issue to pay for a range of improvements, including the new repertory theater that was named for Bagley Wright. Subsequent capital levies in 1991 ($49.9 million) and 1999 ($72 million) were approved by voters, the latter helping to finance McCaw Hall and build Fisher Pavilion.

Space-Age Look and Feel

The defining architectural elements of the World’s Fair were those associated with technology, progress, and the space age. These included the Monorail, the Space Needle, and the Science Pavilion, which reopened as the Pacific Science Center five days after the fair closed. The Monorail, which carried fairgoers between the fairgrounds and downtown, was built by Alweg Rapid Transit Systems, based in Sweden, which underwrote the entire construction cost of $3.5 million. During the six months of the fair, the Monorail carried more than 8 million visitors, allowing Alweg to recover its initial cost and turn a profit. In 1963, the Monorail was turned over to Century 21 Center at no cost. It went on to carry some 600,000 passengers in just four months during the summer, grossing $216,000. In 1965, the City of Seattle purchased the monorail system from Century 21 Center for $600,000. During the 1980s, monorail stations and trains were upgraded. Always popular with local residents, monorail supporters floated two initiatives to expand the system, but those efforts failed, mainly due to funding. In 2003, the monorail cars were given landmark status by the Seattle City Council.

Construction of the Space Needle was begun April 17, 1961, and completed that December. During the six months of the fair, the iconic symbol of the Seattle skyline welcomed some 2.3 million visitors. During the 1960s, at least two Seattle radio stations, KING and KIRO, broadcast regularly from atop the Needle. Twenty years after the fair, though, the tower's appeal had started to wane. To spruce things up, a new restaurant and banquet facility were added in 1982, and the structure was given landmark status in 1999. Another wave of renovations was carried out in 2000, which added a pavilion level, retail store, observation deck improvements, exterior lighting, and more. In 2017, two expansive floor-to-ceiling glass viewing areas, along with other improvements, were created to enhance the visitor experience.

The distinctive cluster of white buildings with their pools, fountains, and dramatic arches, which had been the Science Pavilion during the fair, reopened to the public as the Pacific Science Center. The structure was designed by local architect Minoru Yamasaki (1912-1986), who later became the lead architect for New York’s World Trade Center. After his visit to the fair, British journalist Alistair Cooke wrote, "In its six months of existence the United States Science Pavilion has towered over every other exhibit in popularity as it does in distinction ... It is not possible, you say to yourself, that this Pavilion could begin to match inside the beauty of its exterior. You are wrong ... The result is a single philosophical conception of remarkable majesty" (Duncan, 101). Thanks to the vision of Science Center director and zoologist Dixy Lee Ray (1914-1994), the museum soon found its niche. "The new museum began with leftover fair pieces, like a model of the moon and the Spacearium screen, a precursor to Imax. Dixy, with her signature pageboy haircut and abrupt manner, brought children into the space. She launched a Science Circus during school breaks, and instituted ticket fees and membership" ("8 Legacies That Visionary Women Gave Seattle").

Music and Theater

In 1963, the Seattle Repertory Theatre was founded along with venues for opera and ballet. "Buoyed by the cultural success of the 1962 World's Fair, a handful of community leaders — with Bagley Wright (1924-2011) at the helm — envisioned for Seattle a professional theater company to rival the best in New York" (Timeline, Seattle Repertory Theatre). Its first production was Shakespeare’s King Lear, staged in November 1963. By 1983 the Rep had moved into the new Bagley Wright Theatre, and the Playhouse was renovated to accommodate the Intiman Theatre. In 1990, the Rep won a Tony Award for outstanding regional theater. In 2022, it is the largest nonprofit resident theater in the Pacific Northwest.

Spokane native and architect James J. Chiarelli (1908-1990) rebuilt the Civic Auditorium with a brick façade and it was renamed the Seattle Opera House. The Opera House would serve as home to concerts by the Seattle Symphony Orchestra and productions staged by Seattle Opera and Pacific Northwest Ballet for 40 years. On April 21, 1962 – opening day of the Seattle World’s Fair -- Van Cliburn inaugurated the venue with a performance of Rachmaninoff’s Piano Concerto No. 3 and Igor Stravinsky conducted the Seattle Symphony in a performance of his Firebird Suite. Seattle's opera scene was uplifted in 1964 when Glyn Ross was recruited to run the Seattle Opera Association. "Ross, a veteran of opera companies and festivals in Los Angeles, San Francisco, Naples, and Bayreuth, could sell opera tickets at a heavy-metal concert if he put his mind to it" (Duncan, 98). Attendance also soared at Seattle Symphony events under the direction of Milton Katims and then Gerard Schwarz. And in 1965, Seattle native Robert Joffrey came home for an extended residency with his dance company at the Opera House. By the late 1960s, theater, symphony, opera, and ballet all had found success at Seattle Center.

Food, Fun, and Games

The Fun Forest, an amusement park with carnival-style games, rides, and food booths, was popular with the younger set when it first opened. "Operators Jerry and Beverly Mackey and their partners, Bill and Stella Aubin, began with games and, in 1964, added the rides. There was the popular Wild Mouse roller coaster, the Kiddy Carousel and a 90-foot Velare wheel" ("45-year-old Fun Forest Gets Two More Years"). But significant debts and declining attendance, coupled with a changing vision of what Seattle Center meant to the city and its residents, led to the closure of the Fun Forest in 2009. The popular Skyride attraction fell by the wayside much earlier, in 1982, to make way for construction of the Bagley Wright Theatre.

The Armory was built in 1939 for military storage and used as a National Guard training facility. During the fair, the building housed food concessions. In the early 1970s and for the next 40 years, the Armory was known as Seattle Center House, home to theaters, a high school, children’s museum, offices, shops, and a food and events hall -- the Food Circus. In 2010, the Art Deco and Moderne-style building received landmark status. During a renovation in 2012, the building took back its original name, Seattle Center Armory. The remodeled Armory houses an extensive food hall, several theaters, and a school.

The major sports arenas at the Center also went through several metamorphoses following the fair. The original Coliseum, designed by Paul Thiry and built at a cost of $4.5 million, was sold to the City after the fair to use as a sports arena and convention space. It was the home of the Seattle SuperSonics basketball team, the Seattle Totems hockey team, Seattle University basketball, and, later, the Seattle Storm basketball team and the Seattle Thunderbirds hockey club. In 1995, the Coliseum was renovated and renamed KeyArena. It saw "its share of history-making events over the years, from concerts by the Beatles, Pearl Jam, and Elton John to three NBA Finals and the 1990 Goodwill Games. But an overhaul of the out-of-date venue was needed before Seattle could acquire an NHL or NBA franchise" ("Climate Pledge Arena in Seattle Opens ..."). On October 19, 2021, following extensive renovations, the new Climate Pledge Arena opened on the same site. The 17,400-seat arena, home of the Seattle Kraken hockey team and the Seattle Storm, reused the original 44 million pound roof from the Thiry-designed arena.

Neglect, then Revitalization

From its inception, Seattle Center has teetered between periods of neglect and growth. Several master plans were created and implemented to better "integrate the site into the fabric of the city ... As Seattle’s population, demographics, and economy shifted over the years, what Seattle’s citizens asked of the Seattle Center also changed and evolved. This has created several challenges with regard to the built environment: city officials have wished to encourage growth while celebrating the fair’s legacy, yet have been faced with deterioration in virtually all of the fair-era buildings. Nevertheless, a number of bond measure approvals have given the Seattle Center the ability to patch and repair several of its buildings, and public/private partnerships have assisted as well" (Seattle Center, SAH Archipedia). In 1987, the Seattle City Council hired Walt Disney Imagineering, Inc., paying Disney $475,000 to make a detailed study and development plan for the Center. "Some rebuilding suggestions echoed the earlier Paul Thiry plan. Disney recommended a smaller Center House, a grassy 'Memorial Meadow' on the stadium site, a parking garage, a grand Broad Street entrance, a new children's area, improved landscaping and a large pond near the International Fountain ... The cost, of course, was prohibitive -- an estimated $335 million" and the city rejected it (Duncan, 122).

Over the years, Seattle Center became a destination for people to congregate and observe significant events. On April 7, 1968, a mass of people mourning the death of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. marched to Memorial Stadium for a tribute to the slain civil rights leader. On July 10, 1969, the Center's staff hosted a salmon barbeque at the Exhibition Hall to welcome the first U.S. soldiers back from Vietnam. On April 10, 1994, thousands gathered at the International Fountain to remember Kurt Cobain, who had committed suicide a few days earlier. Impromptu gatherings took place after the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, and on September 15, 2001, people were encouraged to bring cut flowers to fill the basin of the International Fountain in a demonstration of solidarity and remembrance for those who died during the attacks.

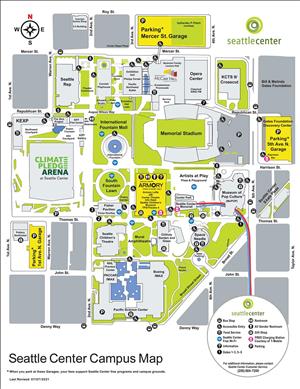

By the early 2000s, there were more than 30 public buildings on Seattle Center's 74 acres. Most years, the venue hosts several major festivals including Bumbershoot (founded in 1971), the Northwest Folklife Festival (1972), and Festál, a celebration of diverse world cultures. In 2018, more than 12 million people enjoyed the Center grounds or attended an event there. More than 14,000 shows and events were presented at the Center during one year, supported by some 250 full-time employees and hundreds of part-time workers. Since 2000, new attractions have drawn more diverse audiences, spanning age groups, cultures, and interests. These new venues included the Experience Music Project (which in 2016 changed its name to the Museum of Popular Culture, or MoPOP), Chihuly Garden and Glass, Skate Park, and the Vera Project, an all-ages space hosting concerts, readings, and events for youth.

Into the Future

In 2006, as Seattle Center approached its 50th anniversary, a master-development planning process was launched. A citizens committee was appointed to identify ways to unify the physical spaces of the Center, reinforcing its role as an arts, recreational, and civic hub. More than 60 meetings were held during the next two years to seek opinions from a variety of audiences. The committee drafted a set of planning and design principles to guide future development. In August 2008, a 20-year, $570 million master plan was adopted by the Seattle City Council to be supported by funds from both the private and public sectors. The plan addressed building renovations, better pedestrian and transportation connections, improved retail and dining options, and sustainability concerns. "The Master Plan looks at the whole campus from the ground up – placing ecological systems in all landscape features, increasing green acreage and reducing the Center’s carbon footprint through energy conservation measures" (Campus Redevelopment Plan).

Today (2022), Robert Nellams serves as Seattle Center General Manager, a position he has held since Anderson stepped own in 2006. In addition to the aforementioned venues, the campus is home to two FM radio stations (KEXP and KING), a television station (KCTS-9), a news outlet (Crosscut), three playhouses (including the Seattle Children's Theatre), three movie theaters, two exhibition halls, a theater studio, and an art gallery. The northeast corner of the site is anchored by Memorial Stadium, which has been targeted for the wrecking ball but remains a bustling venue for high school football and soccer games. It is owned by Seattle Public Schools, which also operates the arts-oriented high school, The Center School, in the nearby Armory building. Seattle Center kicked off its 60th anniversary on April 21, 2022, with music, a spoken-word performance by youth poet laureate Zinnia Hansen, and birthday cupcakes. The celebrations continued for six months.