Coast Salish Indians fished, hunted, and gathered shellfish along Elliott Bay for millennia before May 1792, when European sailors first gazed at the site of present-day Seattle. Sixty years later, U.S. settlers began building a sawmill and wharf on the muddy shores of today's Pioneer Square. Maritime trade was crucial from that first day, and Seattle's harbor defined and energized the city's development over the next century and a half. This overview summarizes the history of the Seattle waterfront. The evolution of individual piers is further elaborated in Parts 2 to 10.

Natives and Newcomers

Prior to Puget Sound's Euro-American settlement, Coast Salish Indians camped in what would become downtown Seattle during regular treks between Puget Sound and Lake Washington via the Duwamish and Black rivers. The members of the Duwamish and Suquamish Tribes hunted in the forests bordering today's Elliott Bay, fished for abundant salmon in its waters, and gathered shellfish on beaches and on the tideflats around the mouth of the Duwamish River.

British Navy Captain George Vancouver led the first European expedition into Puget Sound in 1792, although the Spanish had previously ventured as far south as the San Juan Islands. Vancouver named the vast estuary for Lt. Peter Puget, who conducted soundings between Bainbridge Island and Tacoma. Hudson's Bay Company trappers later entered the area and established Fort Nisqually in 1833 near present-day Olympia.

U.S. Navy Lt. Charles Wilkes surveyed Seattle's future harbor in 1841 and named Elliott Bay for one of his crewmembers. His chart shows the steep ridges that lined the bay north of a level spit, named Piner's Point, surrounded by murky tideflats near the mouth of the Duwamish River.

Settlers and City-Builders

Great Britain ceded its claims south of the present U.S.-Canadian border in 1846, and U.S. citizens began pouring westward by ship "around the Horn" and by wagon train over the Oregon Trail. Seattle's first U.S. settlers arrived in the fall of 1851, establishing a trading post on West Seattle's Alki Beach (dubbed "New York, By and By") and farms at the mouth of the Duwamish River.

In the spring of 1852, many Alki settlers led by Arthur Denny relocated to Piner's Point as the center of a new village later named in honor of Duwamish Chief Noah Seattle. (Chief Seattle and most of the city's original residents departed for nearby reservations under an 1855 treaty, which was followed by a brief "Indian War" in 1856).

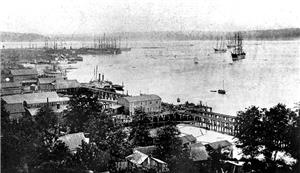

In the fall of 1852, Henry Yesler picked Seattle as the site for Puget Sound's first steam-powered sawmill, which he built on a wharf at the end of "Skid Road," now Yesler Way. Shipments of lumber from this mill to San Francisco and Hawaii fueled the local economy and spurred development of new piers and enterprises.

Steel, Fire, and Gold

Seattle hoped to become the terminus for the new Northern Pacific Railroad, but lost out to Tacoma in 1873. The discovery of nearby coal fields spurred development of the town's first local railroad and construction of additional piers north and south of Pioneer Square.

Seattle's population had climbed to 40,000 by 1889, when, in June, the "Great Fire" destroyed most of the city. Reconstruction was swift, creating most of the buildings in today's Pioneer Square and new piers along a plank "Railroad Avenue" owned by the Northern Pacific.

The Klondike Gold Rush of 1897-1898 made Seattle "The Gateway to Alaska" (from where gold seekers traveled to Canada's Klondike River) and financed more waterfront development and a thriving "Mosquito Fleet" of local steamships and ferries. With completion of the Great Northern Railway in 1893 and additional transcontinental rail links, the city also became a major port for trade with China, Japan, and the Philippines. Seattle celebrated its Pacific Rim links in 1909 with its first "world's fair," the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition, held on the University of Washington campus.

The Port of Seattle Takes Over

Seattle began filling in the vast tideflats south of Pioneer Square in the early twentieth century, producing Harbor Island and the area now occupied by Union Station, King Street Station, Seattle's sports stadiums, and much of the city's industrial base. Growing resentment of railroad and shipping monopolies led King County voters to create the Port of Seattle in 1911 in order to guide harbor development for the public interest.

Maritime development was aided by completion of the Lake Washington Ship Canal in 1917, allowing passage from Puget Sound to the fresh waters of Lake Union and Lake Washington. The shipping slump after World War I and during the Great Depression retarded further improvements. Thanks to federal aid, however, the city replaced the wooden Railroad Avenue with a seawall and Alaskan Way in the mid-1930s.

World War II boosted shipping and led the Port to develop the Seattle-Tacoma International Airport. Today's central waterfront pier numbers also date from the 1940s, when the federal government imposed a uniform system in order to better manage shipments of troops and supplies.

The State and City constructed the Alaskan Way Viaduct in the early 1950s to divert Highway 99 traffic from downtown streets, but it also walled the harbor off from the city. Meanwhile, port activity stagnated as shipping technologies outstripped Seattle's antiquated facilities. Little new was built on the waterfront other than the Edgewater Hotel, which was begun (but not quite finished in time) for the 1962 World's Fair.

From Containers to Cruise Ships

In the early 1960s, the Port of Seattle made a farsighted commitment to handling containerized cargo, which led to construction of today's vast Pier 46 and similar facilities on Harbor Island and along the Duwamish Waterway. As a result, Seattle today ranks as the West Coast's second busiest port, and the fourth most active in the nation.

Concerted recreational development of the waterfront began in the 1970s with conversion of older pier sheds to house shops and restaurants. At the same time, Seattle rehabilitated much of Pioneer Square and Pike Place Market, and built Myrtle Edwards Park, Waterfront Park, and the Seattle Aquarium. In 1982, these historical and waterfront attractions were linked together by service on the Waterfront Streetcar.

The implementation of a new urban design for the waterfront advanced in the mid-1990s with construction of the Port of Seattle's modern headquarters at Pier 69 and the opening of its Bell Street Pier complex, which began serving Alaska-bound cruise ships in the spring of 2000. New condominiums, a World Trade Center, and other "upland" projects have also been completed, and a major waterfront hotel and expanded aquarium are being planned for the early twenty-first century.

Metropolitan King County, where a few thousand Salish once hunted and fished, is now home to more than 1.6 million citizens. Like the community it serves, Seattle's central waterfront has undergone a profound transition from frontier anchorage to international port in a mere century and a half, and the pace of change seems only to accelerate.

To go to Part 2, click "Next Feature"