The 1936 Olympic Games in Berlin were designed to demonstrate the superiority of German athletes, or in the words of the nation's chief propagandist, the Aryan "master race." The Nazi sports apparatus provided promising athletes generous subsidies that allowed them to train incessantly, amateurs in name only. They did triumph in many sports, winning more medals than any other country. But in some competitions the Germans were not the masters. They did poorly in track and field events, where Jesse Owens, a Black American athlete, ran and jumped his way to four gold medals. In other areas the Germans did dominate. In the seven rowing competitions (all male competitors), German oarsmen took the gold medal in five races and the silver in a sixth. Then in the final and premier event, they came up against the University of Washington's eight-oared crew. The Huskies had enjoyed no subsidies, and public donations were needed to pay their way to Berlin. Despite illness and adversity, they eked out a victory over the German and Italian crews (both from fascist-ruled countries) in what is still considered perhaps the greatest eight-oar race of all time.

Rowing – The Basics

There are two broad categories of rowing competition, sculling and sweep rowing. In sculling, each participant handles an oar in each hand. In sweep rowing, each crewmember has a single oar. A sweep shell with eight oars always carries a coxswain, or cox'n, seated in the stern facing forward, to steer and be the on-the-water coach.

The rower nearest the stern is the stroke, often the person with the best technique. The stroke faces the cox'n and sets the rhythm for the crew, which the cox'n calls out and the others follow. It sounds straightforward enough, but eight-man crew racing requires tremendous stamina combined with a precise coordination of effort greater than that in any other sport. One poor stroke by a single rower can cost a race.

Eight-oar rowing competitions originated in England in 1829 in a duel between Oxford and Cambridge, which Oxford won. In 1852, rowing became America's first intercollegiate sporting event, and as in England the contestants were two of the oldest and most elite universities. Yale students bought an eight-man boat in 1842 and established the nation's first collegiate boat club; Harvard followed suit the following year. In 1852 on the placid waters of Lake Winnipesauke in New Hampshire, they finally faced off. Harvard won. The Harvard-Yale race became an annual event and celebrated its 170th anniversary in 2022.

Eight-oared racing shells are approximately 60 feet long and very narrow. The first ones were heavy, with overlapped planking. In the 1870s the first composite shells, made from papier-mâché saturated with a varnish or glue, light but fragile, were used, almost exclusively in America. Next came thin strips of Spanish cedar nailed or screwed to temporary forms, sanded smooth, and finished with multiple layers of marine varnish. In 1927 George Pocock (1891-1976), the legendary shell-builder on the University of Washington campus, inspired by Native American canoes, started using Western red cedar, lighter and cheaper than the Spanish variety and native to the Northwest. Eventually, nearly every major racing program in the country used shells made by Pocock, his brother Dick (1889-1967), and later by George's son Stan (1923-2014), who developed the first fiberglass shell in 1956. Modern shells are usually made of carbon-fiber-reinforced plastic with a honeycomb structure. Next to hydrodynamics, the most sought-after quality in a shell is stiffness, which prevents the forces exerted by the rowers being wasted in torquing the boat.

Crew at the U

When the University of Washington moved to a 600-acre site in Montlake in 1895, it was inevitable that rowing would become a popular student pastime. On the east, the campus fronted on Union Bay, a calm backwater of Lake Washington. To the west, on the other side of the then-intact Montlake isthmus, lay Portage Bay, an equally placid appendage to Lake Union. In late 1899 a Seattle attorney, E. F. Blaine (1857-1942), offered to raise the money to construct a rowing shell for a student crew. Within a year, the school had two four-oared rowing gigs, and in 1903 the UW crew won its first intercollegiate race, beating the University of California (Berkeley) on Lake Washington, with both crews using relatively clunky training gigs. In 1904 rowing was recognized as a sport by the university, although still supported only by student-association funds and private contributions.

UW rowers competed in only three more intercollegiate races over the next four years, but this changed in 1907 when the team purchased two eight-oared shells from Cornell University. Cal bought three similar boats. Eight-plus racing began on the West Coast; an annual competition was held pitting crews from Washington, Cal, and Stanford. Now, with legitimate eights, West Coast rowers could aspire to compete some day against crews in the East.

Sometime between 1904 and 1908 (accounts vary as to just when), Hiram B. Conibear (1871-1917), a UW football and track trainer, agreed to coach the Husky oarsmen. He knew virtually nothing about rowing, but a decision he made in 1912 proved pivotal to the program's success. On a gusty day that spring, the English-born Pocock brothers, shipwrights who worked from a floating workshop anchored in Coal Harbor in Vancouver, B.C., noticed a man in a rowboat thrashing away with the oars in a manner George Pocock described as "like a bewildered crab" (Brown, 45). He seemed to be trying to reach their shop, although it was hard to be sure. When he finally made it and was helped aboard, he "stuck out a large hand, and boomed out, 'My name is Hiram Conibear. I am the rowing coach at the University of Washington'" (Brown, 45).

Conibear eventually lured George and older brother Dick (1889-1967) to Seattle, claiming a need for a dozen eight-oared shells, while barely having enough money for one. Their arrival in 1912 marked the beginning of a decades-long collaboration that would see UW crews reach the pinnacle of their sport. On April 19, 1913, on a four-mile course on the Oakland Estuary, using a Pocock shell for the first time, the UW crew defeated Stanford by 12 boat lengths and Cal by 20, astounding margins. This won them the right to participate against Ivy League universities for the first time.

Trimming the Ivies

The Intercollegiate Rowing Association (IRA) was formed by Columbia University, Cornell University, and the University of Pennsylvania in 1894, a response to Harvard and Yale's refusal to let other colleges compete in their annual regatta -- the elite of the elite rejecting the merely elite. In 1895 the IRA held its first races, on the Hudson River at Poughkeepsie, New York, with the winners claiming the national collegiate championship, the Varsity Challenge Cup, and the chance to represent America at the Olympic Games (after rowing became an Olympic event in 1900. It had been included in the first modern Olympics in 1896, but canceled due to bad weather.) The annual race in New York became known as the Poughkeepsie Regatta.

After the April win at Oakland, money was raised locally to send the UW oarsmen east with their Pocock shell. On June 31, 1913, they raced at Poughkeepsie against crews from Columbia, Cornell, Pennsylvania, Syracuse, and Wisconsin over a four-mile course, placing third, a little less than five seconds behind the winning crew from Syracuse, but only two seconds behind the favored Cornell. These upstart boys from what was still perceived by many as the wilds of the Northwest frontier had done unexpectedly well against the nation's premier college oarsmen. Soon the Pococks were being flooded with orders from universities and rowing clubs around the nation. Donations poured into Conibear's program from the public, enough to finance two new eight-oar shells and some training boats for women rowers. That winter the Pococks left their Vancouver shop for good and made America their home.

UW crews returned to Poughkeepsie in 1914 but did poorly and would not go east again until 1922. In the eight-oar final that year, Navy set a record for the now two-mile race, beating the Huskies by less than three seconds. (From 1919 to 1922 UW athletes had been called the Sun Dodgers, in part because it was the only large university in the West without a representative mascot.)

In 1918 the Huskies moved into a surplus Navy seaplane hangar on the north shore of the Montlake Cut, where George Pocock also set up shop. The crew returned to Poughkeepsie in 1923 and took its revenge on Navy, winning by slightly more than three seconds. Then came a remarkable run of 13 years during which the Husky eight took the Varsity Challenge Cup in 1924 and 1926 and placed second in 1925, 1927, and 1928. Except in 1930 the Huskies never finished farther back than third. In 1927 Al Ulbrickson (1903-1980), the stroke on the Husky team that won at Poughkeepsie in 1923, took over as coach, a job he would hold for the next 30 years.

Germany

After its 1918 defeat in World War I, Germany spent more than a decade as a pariah state, cast out from the community of industrialized nations and excluded from the Olympic Games in 1920 and 1924. Readmitted to the 1928 competition in Amsterdam, Germany won 39 medals, a credible second to the 56 won by the United States.

In 1931 the International Olympic Committee (IOC) selected Germany for the 1936 summer games, a recognition of what at the time seemed to be the country's gradual return to international legitimacy. At the 1932 Los Angeles Summer Olympics the impoverished Germans did not fare well, winning only 24 medals, far behind America's 110. Adolph Hitler (1889-1945) came to power the following year, taking charge of a nation with a moribund economy and nearly 5.6 million unemployed, almost twice that of any other European country.

Hitler and the Nazis soon eliminated all political opposition and ruled by decree. There followed increasingly vicious anti-Semitism, the establishment of concentration camps and an oppressive surveillance apparatus, and the harassment, confinement, or killing of opponents and those deemed undesirable in a racially pure Aryan state.

The Nazification of all aspects of German life extended to sports. The Reich Sports Office supervised the activities of nearly all sports organizations and clubs, including the German Olympic Committee. Athletes in Nazi-controlled sports organizations who showed promise were given special treatment and heavily subsidized. Even so, Hitler had scant interest in hosting the 1936 Olympics. It was Joseph Goebbels (1897-1945), Germany's evil but canny Minister for Public Enlightenment and Propaganda, who convinced him that the games "could advance the Nazi cause and showcase the German 'master race'" ("The Man Behind Hitler").

The facilities built for the games were monumental, the opening ceremonies painstakingly choreographed and upbeat, the overt anti-Semitism in the Nazi press muffled. Still, several European countries (almost all of which would be invaded and subjugated by Germany within four years) saw unsuccessful efforts to boycott the games. A boycott proposed by the Amateur Athletic Union in the United States also fizzled.

The games proved to be both a propaganda bonanza and an athletic success for Germany. Its athletes won 101 medals, including 38 gold. The closest runner-up was the United States with 57 total, 24 gold. But German athletes met little success in the 29 track and field events, where the most serious rebuke to Goebbels's hope for domination by his "master race" was delivered by Jesse Owens (1913-1980), an African American athlete who won four gold medals.

One area in which the Germans dominated in 1936 was rowing, taking gold in five of the seven events and silver in a sixth. In the elite race, the men's eight plus coxswain, the United States had taken the gold in six of the eight previous Olympics. This year would be no different.

The Road to Berlin

Coming into the early 1930s, Cal Berkeley had built a strong rowing program, with the men's eight winning the Varsity Challenge Cup and Olympic gold in both 1928 and 1932. No races were held in 1933 because the Great Depression had stressed the finances of many of the participating universities. In 1934 and 1935 the Huskies lost to Cal at Poughkeepsie, decisively. Things would be very different in 1936. On June 22 that year at 8:00 p.m. on the Hudson River course, UW crews swept all three races of the Poughkeepsie Regatta, the first time that had been accomplished by any competitor since 1912. They beat Cal by almost four seconds in an overwhelming display of rowing power and technique that moved Robert F. Kelley of The New York Times to write:

"Washington won all three races on the Hudson River today … There can be no higher tribute paid the youngsters from the Pacific Northwest than that simple statement of fact. They wrote with their white-tipped oar blades the most eloquent story that can be written about them" ("Washington Gains Sweep …").

The Huskies were headed for the Olympic Trials two weeks later on Lake Carnegie at Princeton, New Jersey, where they would row against crews from Penn, Cal, and the New York Athletic Club. On July 5 they beat them all, starting last and laying back before passing NYAC and Cal (despite using a lower stroke count). For the final stretch the Husky rowers kicked the pace up to 40 strokes per minute and stormed past Penn, setting a new course record. The doyen of Seattle's sports press, Royal Brougham (1894-1978), described that final push: "The crew they thought couldn't sprint caught a well-drilled Pennsylvania boat 400 meters from the finish and zoomed past the startled Easterners like the Queen Mary going by a lighthouse" ("Huskies Win Olympic Tryouts …").

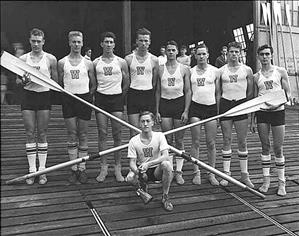

After much experimentation, Ulbrickson had found his perfect crew, one that would never lose a race: Bobby Moch (1914-2005) at coxswain, Donald Hume (1915-2001) at stroke, and oarsmen Joe Rantz (1914-2007), George Hunt (1916-1999), Jim McMillin (1914-2005), Johnny White (1916-1997), Gordon Adam (1915-1992), Charles Day (1914-1962), and in the bow seat, Roger Morris (1915-2009). George Pocock's masterpiece eight-man shell, the Husky Clipper was ready, the crew at peak training. All they had to do was get to Germany.

Now They Tell Us?

On July 6, 1936, one day after the Huskies won the right to go to Germany, Henry Penn Burke (1900-1978), chairman of the U.S. Olympic Games rowing committee, gave U.W. Athletic Director Ray Eckman some dire news, writing:

"We are sorry, but the rowing fund is far short. We are going to have to ask Seattle and the state of Washington to help send their magnificent crew to the games. We have $150 per man on hand, and we need $350 per man more" ("Funds Needed to Help …").

The total needed was $5,000, the equivalent of more than $110,000 in present-day value (2023), although some reports put the shortfall at $4,000. The most desperate days of the Great Depression had waned, but money was still tight. Adding insult to injury, the Olympics committee warned that if the Huskies couldn't come up with the cash, the crew from Penn, a private, wealthy Ivy League university, would be sent in their place. Rather than return to Seattle, the Huskies accepted an invitation from the New York Athletic Club to use its facilities on Travers Island to train while awaiting their fate.

On the same day they reported the Huskies' victory, both the Seattle Post-Intelligencer and The Seattle Times got the fundraising effort going with similar pleas. The P-I's was headlined "On to Berlin!" and ended with "Send the Boys to Berlin." The Times read "On to Berlin, Say Seattle Dollars," and the paper pledged $500 to get the ball rolling. Almost immediately,

"volunteers made phone calls and solicited donations on the streets of Seattle. Loyal fans stepped up with donations ranging from 5 cents to several hundred dollars. Within two days, the Husky community, which had already helped pay for the team’s travel to Poughkeepsie and Princeton, once again came through, ensuring the Washington eight would represent the U.S. and compete for the gold" ("Pulling Together").

On July 14 the Post-Intelligencer ran a boxed statement addressed "TO THE PEOPLE OF THE STATE OF WASHINGTON" and titled "Husky Oarsmen Say 'Thanks.'" It carried the signatures of all nine crew members, two alternates, Coach Ulbrickson, and George Pocock. The statement ended "and to justify your faith in us, success in the Olympic finals MUST be ours" ("Husky Oarsmen Say Thanks"). They all left for Berlin the next day, sailing to Europe on the luxury ocean liner USS Manhattan. The Husky Clipper was carefully stowed on board, by the crew itself, supervised by George Pocock. On July 23rd, the ship made its way up the Elbe River to Hamburg, where the crew and its shell headed for Berlin by train. From there they rode in two buses to the village of Köpenick to be housed in a vacated police training academy, just a few miles from the Berlin-Grünau Regatta Course on the Langer See in the southeastern outskirts of Berlin.

The next morning, the Huskies were taken to the race site, where they shared a new brick and stucco shell house -- with the Wiking Rowing Club, representing Germany. This deserves a slight digression. American victories in these Olympics were often reported in the US press as triumphs over "the Nazi supermen" or similar language. It is true that almost all of the German athletes were the heavily subsidized product of the Nazi-controlled sports organizations, and every German rowing crew but one came from that system. The one that didn't was the eight-man of the Wiking Rowing Club, founded in Berlin in 1896. Not a single oarsman nor the coach had ever been a member of the Nazi party, nor were they subsidized by the Reich Sports Office. While they had to pay lip service to the Nazi state, they made it to the finals simply by beating every Nazi-backed crew they went up against. Dr. Herbert Buhtz (1911-2006), who had won silver in the double-sculls competition at the 1932 Olympics, called the crew's success "a blow for the Nazi selection system" ("The Boys in the German Boat …").

Dogs Dominate

Fourteen nations sent eight-man rowing crews to the 1936 Olympics. They were divided into three groups to compete in round-one elimination heats. The Huskies drew the best lane and won Heat 1 with a time of 6:00.8 (a course record), followed closely by Great Britain at 6:02.1. The next fastest time overall was Hungary, who took Heat 2 with a run of 6:07.6. The Swiss crew won Heat 3 in 6:08.4. The three winners -- the American, Hungarian, and Swiss crews -- all qualified for the final.

There followed three repêchage (French for "fishing out, rescuing") heats in which 10 of 11 remaining crews (Denmark did not participate) competed for a slot in the finals. The crews from Italy, Germany, and Great Britain won, so the six crews in the final would be the Huskies and oarsmen from Italy, Germany, Great Britain, Hungary, and Switzerland.

The Big One

The eight-oared race for the gold was run August 14, an unusually cool day with leaden skies and intermittent drizzle. Seventy-five thousand spectators lined the Langer See's wooded shore. Hitler was there, and Goebbels, and perhaps Reichsmarschall Hermann Goering (1893-1946). The water conditions were described as "extremely bad" ("Huskies Nose Out Italians …") and there was a brisk crosswind from the west coming in at a 45-degree angle. This time the UW crew had the worst lane, the outside, where the water was roughest and the wind strongest, with gusts pushing on the Husky Clipper's starboard side. More troubling, the crew's powerful stroke, Don Hume, had been sick for weeks, since the Olympic trials, The New York Times reporting that he "developed a bronchial complication in [a] chest cold, but expects to row" in the final ("Rowing"). Coach Ulbrickson considered replacing him, but Hume insisted he was good to go.

In mid-morning Seattle time, mid-afternoon in Berlin, the six shells organized themselves along the starting line. Due in part to the wind, neither Husky cox'n Bob Mock nor Great Britain's Noel Duckworth (1912-1980) heard the starting call or saw the flag fall. This gave the four other crews – Italy, Germany, Hungary, and Switzerland – a momentary head start. At 400 meters down the course, Switzerland led, followed by Great Britain, Germany, and the Huskies. At 800 meters the Italians moved into the lead, and UW was last. From there to 1200 meters, the Germans and Italians swapped the lead.

This was quite typical of the Husky crew. Their rowing was so strong, their form so perfect, and their synchronization so precise that using an almost leisurely stroke rate of as low as 32 they could often keep up with and even pass crews wearing themselves out with more strokes.

At 1500 meters, three-quarters of the way to the finish line, Don Hume increased the stroke from 34 to 40, and by 1800 meters they had passed the Italians crew. Victory seemed assured, with only 200 meters left to go. But both the German and Italian teams started rowing faster, well over 40 strokes a minute, with the Italians nearly pulling even with the American crew. Coxswain Mock called on his oarsmen for their "final ounce of energy" ("Fifth Successive Olympic Eight-Oared …"). He got it; in the final few meters the ailing Hume at stroke increased the rate to as high a 44, and the Huskies eked out a narrow victory over the courageous Italian and German crews. The winning time was 6:25.4, far slower than their record-setting qualifying run of 6:00.8., due largely to the poor conditions. Italy won silver with a time of 6:26.0, and Germany took he bronze with a time of 6:26.4. It was considered one of the greatest eight-oared races ever run, with the three top finishers separated by a single second.

There can be no more dramatic descriptions of the race than those penned by the veteran sportswriters who were there. For The New York Times, Arthur J. Daley started his report this way:

"The University of Washington shell leaped like a thing alive in the final ten strokes, broke away from the close pursuit of the Italian and German boats in the last lunge and won for the United States today its fifth consecutive Olympic eight-oared rowing championship.

"In one of the most thrilling finales in the history of the Olympic regattas, the thin cedar prow of the unbeaten and unbeatable Husky Clipper edged across the line of the Langersee [sic] a mere deck's length ahead of Italy with Germany a corresponding distance behind in third place" ("Fifth Successive Olympic Eight-Oared …").

The Seattle Times used the copy of Paul Mickelson, an Associated Press sportswriter:

"Kick … The gallant Washington eight-oared crew will go down in the record books as the mightiest of them all. The Huskies, with a finishing 'kick' that made history, swept everything in sight to earn their fame.

"They should be called the 'Finishers" instead of the Huskies" ("Never to Forget …").

What Makes a Legend?

Just what made the 1936 Husky men's eight crew the stuff of legend? After all, the U.S. had won the men's eight at the previous four Olympics – Navy in 1920, Yale in 1924 (captained by a Rockefeller), and Cal Berkeley in 1928 and 1932.

Many stories characterized the Husky oarsmen as coming from working-class, even hardscrabble roots. This was in large part not true – Bobby Moch's father was a watchmaker and jeweler; Johnny White grew up in the Seward Park neighborhood, his father a steel exporter; Charles Day's dad was a dentist. Only Joe Rantz, who had a lonely childhood and went out on his own at 15, fully fit the legend. All nine, however, spent most of their teen-age years enduring the darkest days of the Great Depression, when life was hard for almost everyone.

Then there was where they hailed from – a relatively small university in the Northwest corner of the country. UW's enrollment in 1935 was 9,200; Cal Berkeley's enrollment the same year was 15,500. Navy and Yale had no difficulty funding the equipment and travel of their crews, nor did Cal. Only the Huskies, the best of the lot, had to rely on public generosity to get from event to event.

And there was this – America was coming out of the worst of the Depression in 1936 and was hungry for heroes. The Huskies were thrilling, and like another public hero of the era, the diminutive racehorse Seabiscuit, the crew had the confidence and the skill to hang back until late in a race, then surge ahead with a blazing display of speed, precision, and endurance. In 1936 these nine boys beat the best the West Coast had to offer, the best the rest of the country had to offer, and the best the world had to offer. They fully deserved all the respect and adoration that came their way.