Chinook Jargon (also called Chinuk Wawa or simply "the Jargon") first saw widespread use as a pidgin language that eased communication between non-Native fur traders and Northwest Pacific Coast tribes. Even before first contact with Euro-Americans, it is thought that Lower Chinook traders used a more limited form of jargon in contacts with distant tribes, including the Nootka (Nuu-chah-nulth) of Vancouver Island and the Haida of the Haida Gwaii islands farther north. Some linguists believe that the Jargon originated with the Nootka in the late 1700s, but it was the rapid growth of the land-based fur trade, beginning with the 1811 establishment of Fort Astoria near the Lower Chinook homeland, that made its use widespread. Over the following decades, from northern California to Alaska, the Jargon became a coastal lingua franca that was used in nearly every context -- court testimony, newspaper advertising, the religious rites and teachings of Christian missionaries, and everyday conversation. By 1875 approximately 100,000 spoke the Jargon, and anthropological linguist and Jargon speaker J. V. Powell estimated that at its peak in 1900 there were 250,000 Jargon speakers — Indigenous, Chinese, Japanese, European, and Hawaiian. Long considered a "dead language" by linguists, there has in recent years been a resurgence of interest, both in academia and among some Native American communities.

Many Theories, Few Facts

The Jargon's vocabulary and word origins are well documented, but details about its history have been the subject of study and, on several points, dispute. Linguists have debated fundamental questions: Just when did the Jargon originate? Where did it originate? How did it expand from a limited fur-trading argot to a quasi-universal language widely spoken by Natives and non-Natives from Oregon to Alaska, coastal and inland?

One inquiry asked whether Chinook Jargon was invented all at once or developed naturally over time. Advocates for the invented theory had a few candidates, including a Jesuit missionary and the Hudson's Bay Company. One historian, A. N. Armstrong, wrote in 1857:

"Among such a vast number of Indians and tongues, it was found that interpreters were not to be procured. It was important that something be done, then, to make a common language, or JARGON, that would be intelligible to all and easily learned. Accordingly a shrewd Scotchman undertook the task, and soon prepared a jargon, that has proved to be inimitable in its way" (Armstrong, 144).

Speculation was that the "shrewd Scotchman" was Dr. John McLoughlin, chief factor of the Hudson's Bay Company's Fort Vancouver in the 1820s and 1830s. But the fact that the Jargon took words from so many different sources and evolved over time to become an increasingly effective language negates the invention theory, and it is no longer considered viable.

Coastal Babel

The Native tribes of the coastal Pacific Northwest were linguistically diverse, with approximately 20 distinct "language families" ranging from the Alaska Panhandle south to California's Sacramento Valley. A language family is "a group of different languages that all descend from a particular common language" ("Language Family"). The three major language families that contributed the most to the Jargon were Wakashan to the north (with seven distinct languages); Salishan, used in a vast area including Puget Sound (approximately 22 distinct languages); and Penution in the south, with approximately 21 languages, including Lower Chinook, Clatsop, and Upper Chinook. Each distinct language within a language family could have a number of localized dialects -- a bewildering welter of tongues.

One of the disagreements that linguists still have about the Jargon is whether any semblance of it existed before the tribes first had contact with non-Natives. There is evidence that two rudimentary trade Jargons, Haida and Nootka, existed before Chinook Jargon, both likely used in northern waters with Spanish and Russian traders early in the second half of the eighteenth century. In April 1778 British Captain James Cook (1728-1779), during his second exploring voyage, reached the west coast of Vancouver Island, the land of the Nootka. One of his crew, Robert Anderson, a gunner with an apparent interest in languages, compiled a dictionary of nearly 270 Nootka words, many of which later appeared in the earliest compilations of Chinook Jargon.

In 1792, during British Captain George Vancouver's (1758-1798) third voyage, some of his officers entered Grays Harbor on the west coast of the Olympic Peninsula and found that "the natives, though speaking a different language, understood many words of the Nootka" (Shaw, Introduction, IX). In 1805, Lewis and Clark were spoken to in the Jargon by Comcomly, who would become a shrewd and influential chief of the Lower Chinook Tribe. None of this can answer with certainty whether any jargon – Haida, Nootka, or Chinook – existed before first contact, but to some linguists it is evidence that one or more did.

Perhaps the strongest argument for a pre-contact trading jargon is simple necessity. Some coastal tribes, notably the Chinook and the Nootka, traveled far from their homelands in large sturdy canoes to trade, and at times to raid and take slaves. There were regular encounters with tribes that spoke different languages, often from different language families. Silent trade in the form of bartering, sign language, and a few shared, perhaps onomatopoeic, words may have sufficed, but many linguists argue that it is much more likely that some sort of jargon developed when trade was exclusively intertribal. As the maritime fur trade with non-Natives expanded, the existing jargon became more robust, and when that trade became land-based it rapidly evolved further, including by the incorporation of more than 150 words whose origins were English and French.

Other linguists disagree, citing the absence of any hard proof and the fact that from the time it was first documented, Chinook Jargon already had a fair number of words taken from French and English. They also point out that there is no record of any Indigenous person referring to the existence of a trading argot before the first contact with non-Native explorers. Linguists on both sides advance recondite lexical and morphological arguments that support one position or the other, but these are incomprehensible to non-linguists, or at least to this writer. It appears unlikely that this disagreement can ever be conclusively resolved.

The spread of the Jargon from a specialized trade language to one of general use is more easily explained. When the fur trade was exclusively maritime, the trading ships would normally anchor offshore to minimize contact with tribespeople, who were considered unpredictable. Starting in 1811 with Fort Astoria (see below) trade increasingly was carried on

"from settled trading posts by men who lived among the Indians, took Indian klootchman (women) as wives, bore sitkum siwash (half-blood) children, and variously were affected by Indian life and customs. A rudimentary pidgin supplemented by signs would be sufficient for haggling over furs and prices, but it was insufficient for everyday conversation. Hence, Jargon grew" (Powell, p. 7).

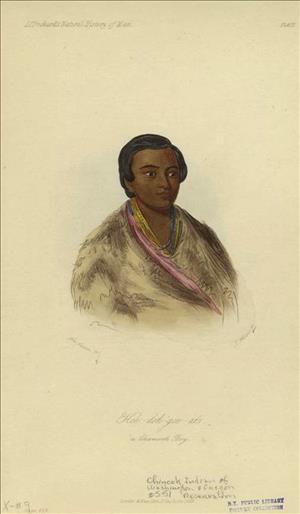

The Chinook

The term Chinookan refers to a people and to several related languages whose speakers occupied both banks of the Columbia River, from its mouth to upstream as far as to the present town of The Dalles, Oregon. The tribal name comes from /činuk/, the Salish-speaking Chehalis's name for a specific Chinook village site.

The Lower Branch of the Chinook lived on the north bank of the Columbia River near its mouth. That strategic position on the river and near the sea gave the tribe a powerful role as middlemen in pre-contact aboriginal trade networks, as well as the later maritime and overland fur trades. Experts at canoe navigation, the Chinook long had traded up and down the river and with tribes on the Pacific Coast as far north as Alaska. Having no trees large enough for making ocean-worthy canoes, they traveled long distances in Nootka-made dugout canoes, for which they frequently traded slaves.

In May 1792 an American ship, Captain Robert Gray's (1755-1806) Columbia Rediviva, became the first non-Native craft to make it over the Columbia River bar and into its tidal estuary. It was followed in October that year by the British ship Chatham, part of Vancouver's expedition. The influence and wealth of the Lower Chinook, placed as they were at the nexus of an extensive trading system, grew dramatically in the following years as ever-increasing numbers of British and American fur-trading ships arrived.

The Companies

In April 1811, men sent by New York entrepreneur John Jacob Astor (1763-1848) began a fur-trading relationship with the Chinook and Clatsop tribes. Astor's enterprise, the Pacific Fur Company, established Fort Astoria on the south bank of the Columbia at its mouth, the first trading-post settlement in the Northwest. When the Montreal-based North West Company learned of it, explorer David Thompson (1770-1857) was sent to establish a British presence on the Columbia. His arrival by ship at Fort Astoria was not welcomed; Astor's people had planned to expand their fur-trading activities upriver. But Thompson ascended the river first, and on July 9, 1811, at the confluence of the Columbia and Snake rivers, he planted a British flag and a sign claiming the surrounding area for Great Britain.

In June 1812 the United States declared war on Great Britain, and Astor sold his Northwest properties to the North West Company, fearing a British warship was on its way to secure the region for Britain. The name of the fort was changed to Fort George in 1813, and working from there the North West Company dominated the coastal fur trade until 1821. That year the British government ordered it to merge with the much larger Hudson's Bay Company (HBC), which had been trading in Eastern Canada since 1640. In 1825 HBC established Fort Vancouver on the north bank of the Columbia, approximately 70 straight-line miles southeast of Fort George. With the arrival of that powerful and far-reaching enterprise, there was a phenomenal increase in fur-trading activity along the Pacific Coast, and a concomitant increase in the need for and requirements of a common tongue. Chinook Jargon was well on its way to becoming a mature pidgin language as it spread, accumulating new vocabulary and nuance. By the second half of the 1800s the Jargon had become pervasive, and in many places was spoken in preference to local Indigenous languages or English:

"For many years the language was used in British Columbia as the working language of canneries and mills, and was often learned by early Chinese immigrants. It was used extensively by Indigenous peoples on both sides of the border, and was also used by [Indigenous] nations both in resistance and in negotiating peace treaties in the State of Washington. Jean-Marie Lejeune, a Roman Catholic priest, developed a writing system using French shorthand and published a newspaper from 1891 to 1904 called the Kamloops Wawa which remains the largest collection of written Chinook Wawa" ("Chinook Wawa").

Jargons, Pidgins, and Creoles

Chinook Jargon fits into the linguistic criteria of a pidgin language. Pidgin languages start as nobody's native tongue. Their shared characteristics are that they

- Quite rapidly spring up from the contact of the languages of two or more significantly different cultures;

- Have a fairly bare-bones grammar and vocabulary and don't conjugate verbs or inflect nouns;

- Are a foreign language to the community of people who use it, i.e. it is not a language that they learned from birth. (Robertson, "Chinook Jargon").

In a nutshell, a pidgin language arises out of necessity and survives so long as it is needed. In some circumstances a pidgin language of longstanding is gradually "depidginized," and becomes the first language of new generations. These languages have richer vocabularies and more complex grammars and are called "creoles," a notable one being the French-based Louisiana Creole. Chinook Jargon never made the transition from jargon to creole, but it came close.

The Jargon developed in a different manner from most pidgin languages. When a dominant culture moves into the territory of a subordinate culture and remains, the usual course is for the dominant language to provide most of the vocabulary for any pidgin language that develops. Not Chinook Jargon; Native words, mostly from Chinook and Nootka, comprise the majority of the Jargon's vocabulary.

And Finally, the Jargon

Counts of the number of words in the Jargon's lexicon range from about 500 to about 700, no doubt because the counting took place during different times in the language's development and spread. For most of the middle decades of the nineteenth century, 500 seems to have been the most commonly accepted count. The first true dictionary of the trading tongue was written by Father Modeste Demers (1809-1871) while at Fort Vancouver during 1838 and 1839. Many more dictionaries came later, for a total of about 50.

George Gibbs (1815-1873) brought wide expertise to the preparation of his Chinook Jargon dictionary in 1863, produced on behalf of the Smithsonian Institution. His short Smithsonian biography notes that Gibbs was

"an ethnologist and expert on the language and culture of the Indians of the Pacific Northwest. A graduate of Harvard University, [he] moved west during the gold rush of 1848 and eventually secured the position of Collector of the Port of Astoria, Oregon Territory. From 1853 to 1855, he was a geologist and ethnologist on the Pacific Railroad Survey of the 47th and 49th parallels under the command of Isaac Stevens. In 1857, Gibbs joined the Northwest Boundary Survey and served as geologist, naturalist, and interpreter until 1862. The last decade of his life was spent in Washington, D.C., where he undertook studies of Indian languages under the auspices of the Smithsonian Institution" (Smithsonian Institution Archive).

He was actually much more. Gibbs was surveyor and secretary for Territorial Governor Isaac Stevens's treaty commission and was responsible for drafting the text of the treaties. He appears to have been more sympathetic to the tribes' plight than most involved in treaty-making. In one intervention that would have huge legal consequences, he convinced Stevens that the tribes would not sign treaties that did not include an explicit and unambiguous promise that "the right of taking fish, at all usual and accustomed grounds and stations" would be guaranteed. (see e.g. Medicine Creek Treaty, Article 3). After years of conflict and litigation, in 1974 Federal District Court Judge George Boldt (1903-1984) issued the famous Boldt Decision, which vindicated the treaty fishing rights of the tribes and strengthened the protections that, at Gibbs's insistence, had been included.

The Jargon was commonly used for everyday conversation, even among non-Natives to some extent. About 300 words, more than half of the total vocabulary, were taken from Native American languages. For a pidgin so limited in both vocabulary and grammar, the Jargon proved unreasonably effective for communication between people who spoke dozens if not hundreds of disparate languages and dialects.

Gibbs produced his Dictionary of the Chinook Jargon, or, Trade Language of Oregon in the years leading up to its 1863 publication. Despite its age, his volume has remained an important part of the Jargon's canon. Gibbs's long study of and fluency in the Jargon led him to extol its virtues:

"Notwithstanding its apparent poverty in number of words, and the absence of grammatical forms, it possesses much more flexibility and power of expression than might be imagined, and really serves almost every purpose of ordinary intercourse …"

"Grammatical forms were reduced to their simplest expression, and variations in mood and tense conveyed only by adverbs or by the context" (Gibbs, Preface, vii).

Gibbs may have been the first to classify the relative contributions of Native and non-Native languages to the Jargon's vocabulary as it then existed (spellings from original):

Chinook, including Clatsop [a dialect of Chinook] — 200

Chinook, having analogies with other languages — 21

Interjections common to several — 8

Nootka, including dialects — 24

Chihalis — 32

Nisqually — 7

Klikatat and Yakama — 2

Cree — 1

Chippeway (Ojibwa) — 1

Wasco (probably) — 4

Kalapuya (probably) — 4

By direct onomatopoeia — 6

Derivation unknown, or undetermined — 18

French — 90

Canadian — 4

English — 67

Many of the English and French words incorporated in the Jargon were nouns that described objects previously unknown to the tribes. Some guttural Native American sounds could not be pronounced by non-Native speakers and were replaced by approximations. Similarly, there were at least two sounds from both English and French that could not be pronounced by Native Americans – f and r – and these were replaced with p and l (e.g. English "corral" became the Jargon's kul-lagh). The buzzing sound of the letter z also was difficult for Native speakers and in many instances was replaced by s.

Much of the Jargon's "flexibility and power of expression," as Gibbs described it, was provided by joining of words to create new words. Just a few examples will suffice.

Bark — S'ick skin (literally "tree skin);

Cord – ten'-as lope (literally "child rope"). Note that the "r" from rope has been replaced by an "l";

To paint – mamook pent (literally, "to make paint"). The verb "mamook" is taken from the Nootka word mamuk (to make, to do, to work). In the Jargon it is often combined with other words to create infinitive-form verbs. Another example: To conceal – Mamook ipsoot (literally, "to make hidden").

French was the language that contributed the second-most words to the Jargon, after Chinook. A Romance language, French nouns are gendered, with the article "le" marking masculine nouns and "la" marking the feminine. These articles were carried over into the Jargon, but their role as gender-determinants was not:

Lacallat, from la carotte (carrot)

Lamestin, from la mèdecine (medicine)

Latet, from la tête (head)

Leclem, from le crème (cream)

Leseezo, from le ciseau (scissors)

How Languages Die

A "dead" language to linguists is one no longer learned as a first language or used in ordinary communication. An extinct language, on the other hand, is a language that no longer exists because there are no speakers or users, academic or otherwise -- a language no one bothers to study at all. This can be the case for small, localized languages that disappear, but it's also true of many ancient languages of which little or no vestige remains.

As mentioned above, pidgins arise from necessity. Some, a very few, mature into creoles and become fully-formed languages. This almost happened with the Jargon in the later years of the nineteenth century, when it was the first language taught to children in some tribes. But pidgins thrive only when needed, and the Jargon proved no exception to the rule. Its demise had several causes, but three were determinative.

First, the Native populations declined dramatically after first contact with outsiders, and that decline only accelerated. Smallpox, cholera, measles, malaria, and a host of other pathogens tore through the tribes in succeeding waves. Although there are significant discrepancies in the counts, the several Chinookan villages in the late 1780s had an estimated population of about 11,000. In 1806 Lewis and Clark counted approximately 900 surviving. The twentieth century saw a slight rebound, to about 1,500. Many now live on the reservation of the Confederated Tribes of the Grand Ronde in Oregon. Losses were even more devastating in some other tribes.

Population decimation left a smaller cohort of Chinook Jargon speakers, and the non-Native population was growing at a rapid rate as the Northwest became increasingly settled in the mid-nineteenth century. As English more and more became the language of commerce, there was less need for the Jargon.

But the most devastating blow to the survival of Chinook jargon resulted from morally indefensible policies adopted by the governments of the United States and Canada. Early in the nineteenth century, an effort began to destroy Native cultures and force their people to become "civilized." The process greatly accelerated in the 1860s. Compulsory off-reservation residential boarding schools were established in both countries. Children were taught that their Native cultures were inferior and forced to shed their traditional clothing and long hair. Native names were replaced with English ones. All classes were taught in English, and children were punished for speaking their own languages (including Chinook Jargon). Their traditional beliefs, rooted in the natural world and having panoplies of gods, were replaced by often-severe forms of nineteenth-century Christianity. A U.S. government study made public in 2022 concluded:

"Tens of thousands of Native American children were removed from their communities and forced to attend boarding schools where they were compelled to change their names, they were starved and whipped, and made to do manual labor between 1819 and 1969, an investigation by the U.S. Department of Interior found" ("Native American Children Endured …").

Any language must pass from generation to generation to stay alive. By forcing Native children to abandon, in fact to forget, the languages they had been raised with, the two governments committed linguicide on a grand scale. Many dozens of Indigenous tongues were lost forever. The Jargon, the one common language widely shared by Natives and non-Natives up and down the Pacific Northwest, used in trade, in religion, in law, and in day-today social interactions, spoken by men, women, and children of all races, origins, and creeds, became by government fiat a forbidden tongue.

Hanging On in Unlikely Places

But the Jargon had deep, and up to a point, lasting penetration. Nard Jones (1904-1972), the longtime chief editorial writer for the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, also wrote novels and heavily anecdotal histories of the Northwest. He was one of the few popular writers to openly mourn the passing of the Jargon, and in 1972 wrote: "Seattle was the last major city to use the hybrid tongue and so the last to abandon it. Now this lost language exists only in the memories of a few ancients and in sparse, well-thumbed dictionaries almost impossible to find" (Jones, 98).

In that same volume, Jones writes that the Jargon hung around in limited circles longer than many thought. Notably, members of Seattle's Arctic Club (a social group established by wealthy individuals who experienced Alaska's gold rush) used the Jargon among themselves until the 1960s. And two of the most prominent men in Seattle for much of the twentieth century were among the last living non-academics to speak the Jargon fluently. One, Joshua Green (1869 – 1975), the founder of Peoples National Bank (among other things), lived to the remarkable age of 105, vital to the last. His early experiences in Puget Sound brought him fluency in the Jargon, and it is said that he retained that knowledge until very near the end. The other, Henry Broderick (1880-1975), became the most influential and successful realtor in Seattle, having started his own firm in 1908. He too lived to an old age, 95, and was remembered by Jones as one of the few who could speak the Jargon "fully" (Jones, 97). Jones noted sadly: "We have a number of this hardy breed still active in Seattle. But they are hard put to find another person with whom to carry on Chinook dialogue" (Jones, 97).

Not Quite Dead Yet

The Jargon may have been ruled dead, but it has not become extinct and remains a topic of study by linguists, anthropologists, and tribal historians and is having a small renaissance as a spoken language. The membership of the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde, comprising over 30 tribes and bands from western Oregon, northern California, and southwest Washington (including Lower Chinooks), have established Chinook Jargon educational programs. These include immersion learning in the Jargon for 3-5 year olds and for students from kindergarten to sixth grade. More limited classes are available for middle- and high-school students, and at Lane Community College. A Chinook Wawa app is available through the Google Play Store.

As described on the tribes' website:

"Our program focus and goal is to provide Chinuk Wawa language immersion in order to create fluent speakers of one of our most recently used Grand Ronde languages, Chinuk Wawa. We strive to strengthen our students' sense of pride and cultural identity through our language and daily hands-on experiences with our culture and place-based curriculum. Parents and families are strongly encouraged to be involved in our students' language revitalization journey by committing to learning and using the language along with their students. The only way for the language to be revitalized in the community is for it to live outside of the classroom and in the homes of our people" ("Chinuk Wawa Education").

Better Late ...

On December 17, 2020, President Joe Biden announced the appointed of Deb Haaland (b. 1960), an enrolled member of the Laguna Pueblo tribe, to become U.S. Secretary of the Interior. In June 2021, Haaland launched the Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative, which, among other things, called for the Department of the Interior to produce the first official U.S. Government investigation into the Federal Indian boarding school system. The study was completed in July 2024 and presented to President Biden.

On October 25, 2024, the President traveled to the Gila River Indian Community in Laveen Village in Arizona to issue a formal apology to Native American peoples for the Indian School system on behalf of the United States government. He said, in part:

"For Indigenous peoples, they served as places of trauma and terror for more than 100 years. Tens of thousands of Indigenous children, as young as four years old were taken from their families and communities and forced into boarding schools run by the U.S. government and religious institutions.

"Nearly 1000 documented Native child deaths, though the real number is likely to be much, much higher. Lost generations, culture and language. Lost trust. It's horribly, horribly wrong. It's a sin on our soul.

"I formally apologize as president of United States of America for what we did. I formally apologize!"

("Biden Apologizes ...").